Custer described Comstock as ‘perfect in horsemanship, fearless in manner, a splendid hunter and a gentleman by instinct, as modest and unassuming as he was brave’

You could see it in his eyes. There was nothing plain about plainsman William Averill “Medicine Bill” Comstock, grandnephew of novelist James Fenimore Cooper, favorite scout of George Armstrong Custer in 1867 and onetime friendly rival of the infinitely more famous Buffalo Bill Cody. Comstock never played up his kinship to Cooper, creator of frontiersman Nathaniel “Natty” Bumppo of the Leatherstocking Tales. Yet, like Bumppo (aka “Hawkeye”), Comstock chose to live as a fearless warrior who often dressed in buckskins and moccasins. Several companions thought he was half Indian, and Comstock did nothing to dispel the notion. He was a man of mystery and contradictions, but all who knew him agreed about his appearance: small in stature, wiry as whip leather and dark in coloring, with long hair tucked beneath a wide-brimmed sombrero and eyes that could pierce like an arrowhead.

W.E. Webb, writing in the November 1875 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, recalls the first time he saw the scout, standing in the doorway of a west Kansas stagecoach station, “He leveled those shining eyes at me with the precision a man would have used with field-glasses….I felt that I had been photographed and could be hunted the world over by him did he ever have occasion.” The best surviving photograph (at left), a carte de visite found among the papers of an army surgeon Comstock befriended at Fort Wallace, Kansas, supports this observation; the eyes staring back are arresting and challenging, the face oddly contemporary.

Comstock not only looked the part of a rugged frontiersman but also had a catchy frontier nickname—“Medicine Bill,” a moniker likely acquired during his pre-scouting days as an Indian trader. Like many aspects of his life, there are several versions of its origin. The artist and Harper’s Weekly correspondent Theodore R. Davis says Arapahos gave Comstock the name after he amputated a tribesman’s rattlesnake-bitten finger, saving the man’s life. Private William Carney of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry told it this way: “One day a young Sioux squaw, while trying to catch a rattle snake, got bit on the finger. Bill, who was standing close by, without a moment’s hesitation, grabbed the wounded finger and bit it off, slick and clean. From this time he was called Medicine Bill.” Either way, the name stuck. He was also called “Will.”

Sometime after he became an Army scout, Medicine Bill squared off against William Cody, who bore an even catchier sobriquet, “Buffalo Bill” (see “Living the Legend: Super Scout Buffalo Bill” in the February 2009 Wild West). Cody de-scribed their famous buffalo-shooting contest in his 1879 memoir, The Life of Hon. William S. Cody: Known as Buffalo Bill, the Famous Hunter, Scout and Guide. Cody, who was hunting buffalo to feed the hungry men building the Kansas Pacific Railway, had heard about the chief of scouts at Fort Wallace. “Billy Comstock….had the reputation, for a long time, of being a most successful buffalo hunter, and the officers in particular, who had seen him kill buffaloes, were very desirous of backing him in a match against me,” Cody wrote. And so the game was set: The winner would be he who shot the most buffalos from horseback in an eight-hour period. The wager was a hefty $500, but the stakes for Cody were much higher. His celebrated moniker hung in the balance.

Natty Bumppo probably would have shunned such mass slaughter—he shot only what he needed to survive—but a Plains scout made his living largely by reputation. Comstock’s weapon of choice was his 16-shot Henry rifle, while Cody was armed with his beloved Lucretia Borgia, a Springfield Model 1866 .50-caliber breechloading rifle known on the frontier as a needle gun. “He could fire a few shots quicker than I could, yet I was pretty certain that it did not carry powder and lead enough to do execution equal to my caliber 50,” Cody wrote.

As it turned out, he was right. Buffalo Bill won the contest with 69 kills, while Medicine Bill finished with 46. Other contemporary references to this event are nonexistent, although Cody said the railroad ran a special excursion train from St. Louis for more than 100 spectators, including Cody’s wife and infant daughter, and champagne cocktails were enjoyed by contestants and onlookers alike. The Kansas Historical Quarterly in its summer 1957 issue placed the shoot-off in Logan County, some 2 ½ miles west of Monument, Kan.

Cody, like Comstock, would soon become a chief of scouts, but unlike Medicine Bill, Buffalo Bill would also be a top showman and self-promoter and live a long life. Cody was a notable exception in the scouting profession; Army scouts on the Plains were often shadowy characters. As Custer noted in his memoir, My Life on the Plains, a wise officer relied on his scout’s skills but did not inquire too deeply into his personal life. “Who they are,” he wrote, “whence they came or whither they go, their names even…are all questions which none but themselves can answer.”

This was especially true of Comstock, Custer’s guide during the lieutenant colonel’s early Indian-fighting days in Kansas. Comstock’s star was on the rise in the summer of 1868, after he dodged a murder rap, but he was not destined for greater fame and fortune. That August the plainsman, still only 26, was gunned down on the plains of western Kansas, his body left to rot in the sun. Today, just over 140 years after his death, it’s possible to visualize the scout who resembled Natty Bumppo, but it’s impossible to truly know this elusive son of the West who made such a strong impression on all who met him.

Contrary to his carefully crafted Western/Indian image, Comstock was born in Michigan in 1842, the son of a prosperous Michigan lawyer and state legislator who had built a fortune in Chicago and Detroit with Indian and military supply trade. Comstock’s mother died when he was 4, his father suffered a reversal of fortune, and young Will was sent to live with relatives. His older sister, Sabina, eventually took him in, perhaps even before her marriage to prominent lawyer Eleazer Wakeley in 1854. Three years later, when Will was 15, Wakeley was named district judge of Nebraska Territory, and the family moved to Omaha. In 1860 a census enumerator found the 18-year-old Comstock working as an Indian trader in Nebraska Territory with two employees and $500 in property. It was likely during this period Comstock gained his knowledge of native culture that later would serve him so well.

In the fall of 1865, Comstock scouted briefly for the Army at Fort Halleck (in future Wyoming), then moved to western Kansas, settling on what came to be known as Rose Creek Ranch. Its meadows produced fine hay—a valuable commodity in this arid, forage-sparse country—which Comstock sold to the newly established Fort Wallace for $20 to $30 per ton. At 200 to 300 tons per year, the scout had a good thing going. But business success was not enough for the adventuresome young man. By August 1866 he had become chief of scouts at Fort Wallace, the westernmost and most Indian-troubled of the Smoky Hill Trail posts. He held that position until death.

Comstock was popular with most everyone at the fort, from the new commander, Captain Myles Keogh of the recently formed 7th U.S. Cavalry, to a canine companion named Cuss, described by correspondent Theodore Davis as an “evil-looking dog.” The post surgeon, Theophilus H. Turner, roamed the prairies with Comstock, hunting and collecting fossils. Probably with Comstock’s help, Turner recovered dinosaur vertebrae in a ravine near an old Indian camp and alerted scientist friends back East. Eventually the vertebrae, determined to belong to an Elasmosaurus platyurus (the longest of the marine saurians discovered to that time), were shown at the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.

Medicine Bill chased horse-stealing Indians with Michael Sheridan, younger brother to Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, and struck up a friendship with Lieutenant George Armes, who later rose to Colonel Armes and wrote of their explorations in his 1900 memoir, Ups and Downs of an Army Officer: “Comstock took me up one of the branches [of the Republican River] where an old village of Indians used to be and where he lived with them some four or five years ago [1862 or 1861] and showed me the graves of a number of Indians he helped to bury in the tops of the trees.”

Carney, a young recruit in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, was among the Fort Wallace soldiers highly impressed by the dashing figure who carried a Henry rifle and looked as if he were born to the Plains. “I had often heard of him,” Carney wrote in a 1900 reminiscence published in Collier’s Weekly, “his wonderful marksmanship and what a great Indian scout and fighter he was…so it was no wonder I was so anxious to see a real, live dyed-in-the-wool Indian scout like Billy Comstock.” Carney, like Turner, seemed to believe Comstock was half Indian, admitting, “He was a person whose nationality would be hard to tell.” Comstock was truly proficient with his Henry, but Carney was wholly mistaken when he suggested the scout “was simple as a child in regard to anything connected with civilization; never had been east of the Missouri River, had never seen a steamboat or a railroad—in fact, knew nothing about such things except to hear of them.”

When Keogh’s boss, Colonel Custer, needed a scout at Fort Riley, Kan., he asked for Comstock, and Keogh obliged, sending Medicine Bill east in January 1867. In his letter of introduction, Keogh described Comstock as “an eccentric genius and an ardent admirer of everything reckless and daring.” In a postscript, the captain added, “Comstock has never yet seen a R.R. train, and his satisfaction, I believe, is improved by this accidental granting of his fondest wishes, viz: ‘seeing Custer and the R.R.’”

The commander took readily to his new scout, with whom he shared an affinity for dogs, hunting and adventure. “No Indian knew the country more thoroughly than did Comstock,” Custer wrote. “He was perfectly familiar with every divide, watercourse and strip of timber for hundreds of miles in either direction. He knew the dress and peculiarities of every Indian tribe, and spoke the languages of many of them.” Custer also described Comstock as “perfect in horsemanship, fearless in manner, a splendid hunter and a gentleman by instinct, as modest and unassuming as he was brave.”

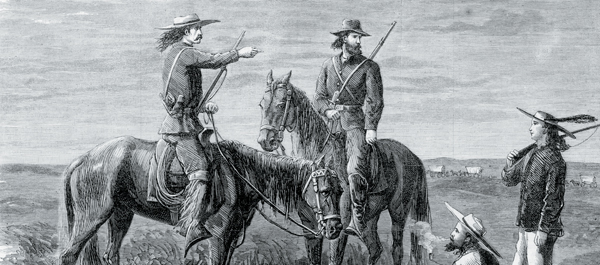

It was during his time with Custer that Comstock met Harper’s Davis, who drew a pencil sketch of him and three fellow scouts. “Will Comstock has lived in the far west for many years,” Davis wrote. “His qualifications as an interpreter and scout are said, by those best qualified to judge, to be unsurpassed by any white man on the plains. He is, moreover, a man of tried bravery and a first-rate shot.” Davis went on to say, mistakenly, the scout was a “Kentuckian by birth.”

In the spring of 1867, Comstock accompanied Custer’s 7th U.S. Cavalry into the field under Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, whose search to find hostile Cheyenne warriors turned into a harum-scarum expedition that did little to advance the reputations of either Hancock or Custer. Comstock, however, distinguished himself, most notably in an episode involving an 11-man detachment under Lieutenant Lyman Kidder that vanished in early July while carrying orders to Custer in the field. Custer quoted Com-stock, who suggested Kidder’s party might be all right if he followed his Sioux guide’s advice, although the spelling and punctuation suggest a man of little education: “Is this lootenint the kind of man who is willin’ to take advice, even ef it does cum from an Injun? My experience with you Army folks has allus bin that the youngsters among ye think they know the most, and this is particularly true ef they hev just cum from West P’int.” Informed Kidder was not from West Point, but had just received his commission, Comstock countered, “Ef that be the case, it puts a mighty onsartain look on the whole thing.”

Within days Comstock found the mutilated remains of Kidder and his party, victims of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers and Sioux. Months later Comstock may have guided Kidder’s father, Judge Jefferson Parish Kidder, to the site to recover his son’s bones for burial in St. Paul, Minn.

After the Hancock Expedition fizzled, Comstock returned to Fort Wallace. In January 1868, though, a strange episode threatened Comstock’s soaring scouting career. The incident contradicts Medicine Bill’s image as an amiable companion, hunting partner and, in the words of correspondent Davis, man who overflowed with “kindly feelings for the human race.” Comstock’s kindly feelings, it seems, did not extend to wood contractor H.P. Wyatt, who cheated him on a business deal. Witness David Burton Long, then a hospital steward at Fort Wallace, recalled the incident in 1903: “I was in the store [of post sutler Val L. Todd] at the time and heard loud talking, when Wyatt got up and was leaving the store, and Comstock pulled out his six-shooter and shot Wyatt twice in the back. Wyatt ran out of the store and fell dead. During the trouble, as Comstock was shooting, I stepped up and tried to prevent Comstock from killing Wyatt, and he turned on me and said, ‘You keep your hands off, or I will kill you.’ Wyatt was taken to the hospital dead room.”

Wyatt may have needed killing; there is evidence he was the notorious Missouri bushwhacker Cave Wyatt, who rode with William Quantrill at Lawrence and later with William “Bloody Bill” Anderson. Even so, Comstock was arrested and taken for trial to Hays City, where it seems friends came through for him. As Long recalled, the “rough element” of the community raised $500 for the scout’s defense. Trial judge Marcellus E. Joyce, a justice of the peace from Leavenworth, also appears to have been in Comstock’s corner. “Did he [Comstock] do the shooting with felonious intent?” Joyce asked Todd, according to Long. “I do not know what his intentions were,” replied Todd, “but I did see Comstock shoot Wyatt, and Wyatt ran out of the store and fell dead.” Joyce said, “If the shooting was not done with felonious intent, and there is no proof that it was, the prisoner is discharged for the want of said proof.”

After this brush with the law, Comstock retreated to his profitable Rose Creek Ranch, but not for long. Despite the Wyatt shooting, the scout remained in demand. The Indians started making trouble again in 1868. General Sheridan, who had replaced Hancock as commander of the Department of the Missouri, ordered Lieutenant Frederick Beecher to assemble a crack team of scouts to keep tabs on the hostiles and negotiate with them if necessary. (For the most part, Sheridan was inclined to agree with Lt. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, who dismissed peace talks with Indians as “the same old senseless twaddle.”) Beecher hired four men—Dick Parr, Frank Espey, Abner “Sharp” Grover and Comstock. Reportedly, Comstock only agreed to take the job after Sheridan personally assured him the Wyatt business was forgotten. At $125 a month, about 10 times the wage of a private soldier, Comstock also received the highest pay of the four.

The assignment, however, marked the beginning of the end for the popular scout. Beecher, whose own days were numbered, ordered Comstock and Grover to find the village of Cheyenne Chief Turkey Leg and convince him to rein in his warriors, who were wreaking havoc in the Saline Valley and along the Solomon and Republican rivers. Both scouts knew Turkey Leg, having lived in his village during their trading days, and they were counting on Cheyenne hospitality, which held that a former friend would be safe in a man’s lodge even if the relationship had soured. The two went ahead with their mission, despite knowing that just days earlier 7th Cavalry soldiers under Captain Fred Benteen had skirmished with Turkey Leg’s warriors, killing four and wounding 10.

Comstock and Grover found the village on Sunday, August 16. Accounts of its location vary, but according to the research of John S. Gray, it lay at the head of the Solomon River, about 25 miles north and east of Monument Station. Comstock and Grover made it to the chief’s lodge safely, but midway through negotiations, runners galloped into the village with news of the Benteen fight. Comstock and Grover left in a hurry.

What happened next will never be known for certain. The official report from Fort Wallace, written by commanding officer Captain Henry C. Bankhead and dated August 19, states: “The Indians then drove Comstock and Grover out of camp, and when about two miles away were overtaken by a party of seven, who at first appeared friendly, and after riding along with them, fired into their backs, killing William Com-stock instantly. Grover remained hid [sic] in the grass during Monday—Monday night walked to the railroad, which he struck about seven miles east of Monument, and sent on to this post….”

In a letter to his father dated August 23, 1868, post surgeon Turner mentions having Grover under his care in the hospital, shot through the lung but with good prospects of recovery. Of Comstock’s death, Turner wrote: “I know of no one whose death would have produced so wide-felt an impression. He is certainly a great loss.”

There were those who suspected Grover of killing his partner to acquire his profitable ranch. “Apparently, that was the opinion of several of the officers at Fort Wallace,” John Adams Comstock noted in A History and Genealogy of the Comstock Family in America (privately printed in 1949). “There are some points in Grover’s account that do not seem possible.” For one, he observed, Grover had recovered enough from his reportedly grave wounds to lead Colonel George Forsyth’s scouting expedition against the hostile Indians just a few weeks later. (That campaign ended in the infamous Battle of Beecher Island, in which Beecher was killed.) And, he notes, Grover did indeed acquire the valuable Rose Creek Ranch following Comstock’s death.

There are other tantalizing accounts. In 1922 Frank Yellow Bull told an interviewer his father had been in the Cheyenne camp the night Comstock and Grover arrived. The two white men argued after leaving, Yellow Bull recounted, suggesting, “Maybe white man shoot white man.” Still, it’s hard to imagine Grover would shoot himself through the lung to escape suspicion. Forsyth did not think him guilty, writing later that men “not to be depended upon” had spread such ugly rumors. Furthermore, Grover did not take immediate ownership of Rose Creek but succeeded Comstock’s employee Frank Dixon after he, too, met a violent end. At any rate, his tenure on the ranch was brief. Grover was killed in a drunken saloon brawl in 1869. His assailant was not charged, alleging that he acted in self-defense.

There is one remaining question: What became of Comstock’s body? Early rumors said the Army had recovered the corpse and reburied it in the post cemetery. Certainly the family believed this. Wrote John Adams Comstock: “General [sic] Bankhead sent out a detachment to bring the body of Comstock into the post, and he was buried there. The grave was the third one south of the northeast corner of the post cemetery.” Only it isn’t. Jayne Humphrey Pearce, president of the Fort Wallace Memorial Association, says there is no record of Comstock having been buried in the post cemetery.

Pearce, who lives in Wallace, maintains an archive of letters and manuscripts written by residents and Kansas historians who have sought Comstock’s final resting place. The documents are puzzling for a reader not intimately familiar with the terrain; some are incomplete, many composed by men who have since joined the scout in the world beyond, but they tell an interesting tale. In one document, written after 1950, longtime area resident Frank Madigan describes a conversation he had with Charles Carmack, a former Fort Wallace ambulance driver, in which Carmack says he buried Comstock’s body on the north bank of the Smoky Hill River, about 300 yards north of Hell Creek. Carmack, who must have been a very old man at the time, died before he could take Madigan to the spot, but Madigan noted several graves in the area, “one in particular that has been covered with rocks, as was described to me by Carmack.”

This may have been the grave Leslie Linville of Colby, Kan., found in 1941. At the time he thought it was that of an Indian, but later he came to believe it was Comstock’s. “He was buried very respectfully in a very shallow grave, perhaps 12 inches deep facing the Rising Sun,” Linville wrote in 1970. “This was a must with the old Frontier Men.” Others agreed, including historian Gray. But in the end, one can only speculate. Such is the case with so many things in Comstock’s life. Although he was, like Buffalo Bill, a highly respected Army scout in Kansas, Medicine Bill didn’t have Cody’s longevity or knack for providing colorful stories, in print or onstage. But Comstock was kindred to Natty Bumppo, with one big difference. He was, despite the mystery and controversy, the real thing—a plainsman who was anything but plain, and a white man from Michigan who died with his moccasins on in the true West.

Author Susan K. Salzer writes from Columbia, Mo. For further reading: Fort Wallace, Sentinel on the Smoky Hill Trail, by Leo E. Oliva; and Ups and Downs of an Army Officer, by George A. Armes.