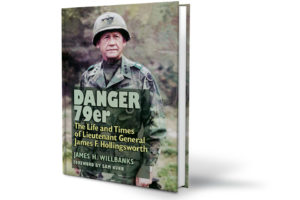

Jim Willbanks’ superbly written, extensively researched book on Lt. Gen. James F. “Holly” Hollingsworth—known by his radio call sign “Danger Seven-Niner”— shows readers why Holly is one of only three Texas A&M heroes with statues on the university’s College Station campus. The other two are Texas legends and A&M presidents: Lawrence Sullivan “Sul” Ross (a Texas Ranger, Confederate general and governor) and James Earl Rudder (famed World War II commander of Rudder’s Rangers, one of the heroes of the D-Day assault at Normandy’s Pointe du Hoc). Rarified company; yet Hollingsworth clearly deserves the honor.

Jim Willbanks’ superbly written, extensively researched book on Lt. Gen. James F. “Holly” Hollingsworth—known by his radio call sign “Danger Seven-Niner”— shows readers why Holly is one of only three Texas A&M heroes with statues on the university’s College Station campus. The other two are Texas legends and A&M presidents: Lawrence Sullivan “Sul” Ross (a Texas Ranger, Confederate general and governor) and James Earl Rudder (famed World War II commander of Rudder’s Rangers, one of the heroes of the D-Day assault at Normandy’s Pointe du Hoc). Rarified company; yet Hollingsworth clearly deserves the honor.

Hollingsworth, born on March 24, 1918, was a “Texas-sized,” Patton-trained, aggressive combat leader who always led from the front (his six Purple Hearts attest to that). Holly excelled in World War II, the Cold War (Europe and Korea), Vietnam and Washington’s “political battleground.” But luck plays a part in any military career, and fortune frequently smiled on this farmer’s son.

After his graduation from Texas A&M in 1940, Hollingsworth was assigned to Maj. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s 2nd Armored Division in time to hone his tank officer skills in the groundbreaking 1940-42 training exercises known as the Tennessee, Louisiana and Carolina maneuvers. Hollingsworth was perfectly positioned to excel in the armored division’s actions throughout the war: bursting through Normandy hedgerows, racing across France and Germany and leading the first American troops into Allied-occupied Berlin.

Hollingsworth’s “lead from the front” command style made him a “bullet magnet,” but despite his frequent wounds, he always wanted to be upfront in combat instead of in a rear command post bunker. And in Vietnam helicopter mobility provided senior leaders the unprecedented ability to directly command combat engagements.

In Hollingsworth’s first Vietnam tour (1966-1967), he was assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division, commanded by the uncompromisingly ruthless Maj. Gen. William E. DePuy—infamous for bragging about how many subordinates he relieved from command. Although the two personally got along, Hollingsworth’s courage and single-minded commitment to his soldiers’ welfare distinguished his outstanding leadership from that of the unforgiving and deliberately callous DePuy.

On Hollingsworth’s second tour (1971-72) he was senior U.S. adviser to Army of the Republic of Vietnam forces in Third Regional Assistance Command, the area north of Saigon to the Cambodian border. That is where he provided his greatest contribution to the Vietnam War. In this section of Danger 79er, the author is clearly in his element—not only is Willbanks today’s finest Vietnam War historian, but he also was one of the embattled U.S. advisers present during the bitter, costly, but ultimately successful effort at the Battle of An Loc, resulting in the defeat of North Vietnamese Army forces in that region during the communists’ 1972 Easter Offensive.

Willbanks describes Hollingsworth’s tremendous impact:“The general’s omnipresence over the city, even in the thickest of the fighting, was one of the major factors that helped sustain the advisers throughout the battle. Even when things looked the worst, he was in the air over the city encouraging the advisers and their counterparts…the old warrior knew that the men on the ground needed his personal encouragement, and he exposed himself repeatedly in the deadly airspace over the city to give it. Even when the advisers were convinced that the defenders…were about to be overrun, the gruff voice of ‘Danger 79er’ convinced them…to hold on…it meant everything to those on the ground at An Loc.”

Perhaps inevitably, Hollingsworth’s aggressive actions ran afoul of his Washington superiors, who were overly anxious to hold up An Loc as an ARVN-led battle that validated President Richard Nixon’s Vietnamization program to put South Vietnamese officers in control of combat operations previously led by Americans.

With Patton-like bluntness, Hollingsworth candidly told reporters he would kill “every one of these [NVA] bastards before they can get back to Cambodia…I’m movin’ to the north and I’m exploiting the success we had at An Loc.” Hollingsworth’s frankness, implying that he, not ARVN commanders, led the fighting, ignited a critical firestorm. But Holly’s luck held. His Vietnam boss, Gen. Creighton Abrams (another Patton-trained fighter) staunchly backed him.

In October 1972, Abrams became Army chief of staff and assigned the fiery Texan to command U.S. forces in another global “hot spot”—South Korea.

Hollingsworth died at 91 on March 2, 2010—Texas’ 174th Independence Day—and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His contributions to the Army and the nation are too many to detail here, but his distinguished service in World War II, Vietnam and the Cold War fully justify his Texas A&M statue. Holly was a soldier’s soldier, an exceptional combat leader whose life is expertly recounted in Willbanks’ outstanding biography.

—Jerry D. Morelock