Construction workers struggled to disassemble the large, marble statue of the Civil War general, but they got the job done. The toppled memorial was hauled off to a remote storage area where it was largely forgotten, surrounded by weeds. At some point, the commander’s nose was broken, and fingers were dislodged from his hand and lost. Due to recent events, one can be forgiven if the assumption is made that this was the recent removal of a Confederate icon’s memorial, but this statue celebrated Union Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, and the year was 1969.

During the current controversies over Civil War memory and public history, memorials to the men in blue, the commanders who defeated the Confederacy, stand silent and largely out of the fray. Yet many monuments to soldiers who defended the Union dot our landscape, and their granite and bronze statues cast shadows in the capital of the nation that they fought to preserve. Ornate tributes to Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and Philip Sheridan command the landscape of Washington, D.C.—physical testaments to the victorious side of the Civil War.

But there is also a statue of George Meade in D.C., one that was put up after the other previously mentioned generals had their shrines, and it stands along Pennsylvania Avenue, at 3rd Street, N.W. The relatively late date of its erection is just another example of how the Army of the Potomac’s longest-serving commander was frequently undervalued during the postwar years.

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]espite taking command of the Army of the Potomac just three days before the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, George Gordon Meade’s leadership at that colossal engagement in south-central Pennsylvania brought that beleagured army its first significant victory in the war. But Meade soon faced criticism for his inability to crush the Army of Northern Virginia before it crossed the Potomac

River on July 14. Less than 10 months after Gettysburg, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, fresh from success in the Western Theater, arrived in Virginia to direct the war’s final campaigns.

After Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, Meade found himself further removed from the accolades of a grateful nation. But Pennsylvanians, due to the fact Meade claimed Philadelphia as his home, were particularly determined to assert the general’s place among the heroes of the Union. The drive to build his memorial, and conflicts over how it should look, prove that the soldiers who served under Meade were determined that the “Victor of Gettysburg” should take his place among the memorials to defenders of the Union in the nation’s capital.

By the time of his death in November 1872, at age 56, Meade had devoted nearly 40 years in service to his country. Localized commemorative efforts commenced shortly after his death, and Pennsylvanians unveiled the first of the Meade monuments in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park in October 1887. Honoring the general also served as an opportunity to assert Gettysburg as the war’s decisive battle and define the general’s role in the victory. “Honor to the memory of Meade,” declared one orator, “who in the darkest hour never despaired, and under whose leadership victory was achieved!”

In 1896 the general was honored with an equestrian monument at Gettysburg, but 31 years would pass until Meade took his place in Washington. The occasion culminated a 16-year effort to bring to fruition a Pennsylvania resolution to secure Meade’s place in the nation’s collective Civil War memory.

Tributes to Meade’s contemporaries, namely Grant, and ironically his Gettysburg adversary, shaped Meade’s commemorative narrative. The unveiling of a Lee statue in National Statuary Hall in 1909 served as a catalyst for a memorial to Meade in D.C. The Philadelphia Brigade Association, a veterans organization composed of men who served in the 69th, 71st, 72nd, and 106th Pennsylvania Infantry, adopted a resolution on March 1, 1910, that stated it was “fitting and proper” that Pennsylvania be represented in the capital with a statue to “her most distinguished soldier of the Civil War.”

The association mobilized additional supporters and approached the state’s governor, who then recommended the matter to the legislature. Supporters linked the appropriateness of the memorial to the general’s Gettysburg success. Lauding Meade’s “military capacity and technical skill,” former Pennsylvania governors and Union veterans Samuel Pennypacker and James Beaver supported the memorial to the man who “determined the fate of the Nation and greatly affected the whole future of the world.”

Thus, on June 14, 1911, the Pennsylvania legislature passed Act No. 742, declaring it “fitting and proper” for a Meade memorial in Washington. The act provided for the creation of a Pennsylvania Meade Memorial Commission. The men, unified by determination to honor their native son, worked in coordination with the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), a federal organization established in 1910 and charged with the responsibility of overseeing the site selection and erection of memorials and monuments in Washington.

The membership of the commissions was quite diverse. Most significant, several of the state’s commissioners were Civil War veterans, while the CFA members had artistic and architectural backgrounds. Daniel Chester French, the era’s distinguished sculptor and acclaimed for his Lincoln Memorial, was among the most renowned CFA members. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., son of the prominent landscape architect, was another distinguished CFA commssioner.

Determining a location for the memorial became the commissions’ first task, as there were already plenty in place or being built. By the time the Meade Memorial was dedicated in October 1927, 17 Civil War related statues complemented Washington’s landscape. These included memorials to Sherman, Sheridan, and, in 1922, at the centennial of his birth, a colossal statue to Grant dominating the area in front of the Capitol’s east side.

Meade’s advocates favored a location near the Capitol along the National Mall and within proximity to the recently authorized memorial to Grant. Thus, on February 5, 1915, commissioners approved a site at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 3rd Street, N.W., on the grounds of the old Botanic Gardens. Plans called for the creation of a “Union Square,” an elegant landscape complete with memorials to “the great military figures of the war,” as well as elaborate fountains and terraces, ultimately rivaling in patriotic expression Paris’ Place de la Concorde.

Conflicting visions for the memorial plagued the commissioners and plans for the memorial stagnated while animosities grew. Pennsylvanians showed unwavering support for Meade, but that also became their most glaring flaw. They championed a grandiose memorial that lauded the general’s military attributes in order to rightfully define his place as a prominent successful commander in the Civil War narrative and in America’s collective historical consciousness. State commissioners perceived the task before them as momentous; it became an opportunity to correct “monstrous wrongs” inflicted upon the general, “wrongs perpetuated all the way from Gettysburg to Appomattox.”

John W. Frazier was arguably the most proactive Pennsylvanian fashioning Meade’s memory. Secretary of the state commission and a veteran of the 71st Pennsylvania, Frazier proved steadfast in his vision for the memorial. Frazier was not interested in producing an opulent classical work of art for the capital’s landscape, but in “performing my duty to Meade.” The aging veteran criticized designs that offered anything less than a militaristic interpretation of his commander. Not surprisingly, Frazier and the artists of the CFA struggled to find common ground. Federal commissioners urged adherence to artistic standards and “the high ideal of the monumental art.” They feared “what these old soldiers want would not prove to be an adornment of Washington.”

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s the Great War raged in Europe, design of the Meade Memorial occurred in incremental, wearisome steps, pitting the Pennsylvanians’ desire to produce a glorious memorial to their native general against the CFA’s aesthetic vision. How best to portray Meade became a subject of contention. By late 1915, the Pennsylvania commission had selected Charles Grafly, a Philadelphian, as the monument’s sculptor. Grafly offered multiple designs. One concept portrayed Meade sitting on a rock, legs crossed, reviewing campaign maps. Neither the state nor the federal commission liked this option, believing it represented Meade too casually and lacked requisite dignity.

After three years of reviewing options, commissioners selected Grafly’s allegorical portrayal of Meade. Frazier aggressively objected to the allegorical design, finding himself at odds with the members of the Commission of Fine Arts and Grafly. Commissioners spilled volumes of ink complaining about Frazier. One CFA member described the Pennsylvanian as a “totally unfit person to transact business with” and considered him “obstructive and insulting.” Others still lamented his inability to comprehend the enormity of the task at hand and even dreaded meetings with the old veteran.

A clear understanding that Meade’s legacy in granite, as in life, needed to be subordinate to Grant’s underpinned conversations for the Meade Memorial. “The Meade Memorial therefore should be related to the Grant Memorial,” a committee member noted, “in such a manner that the two will be complementary and not competitive.” Frazier found Grant’s memorial unimpressive, in any case. Derisively referring to it as a “work of art,” he chided the “African lions” and the “replica of a Roman chariot race.” Notwithstanding some objections, in January 1922 the CFA approved a working model of Meade’s allegorical depiction.

Groundbreaking for the Meade Memorial’s landscaping occurred on March 28, 1922. Key figures in attendance included President Warren G. Harding, Pennsylvania Governor William Sproul, and two of Meade’s descendants—his grandson, George Gordon Meade, and his great-grandson, also named George Gordon Meade. Befitting the occasion, these men made use of the same spade that had been used in the groundbreaking of the Lincoln Memorial and the Arlington Memorial.

A year after the groundbreaking the sculptor company, the Piccirilli Brothers from New York City, began cutting Grafly’s vision into marble. Unfortunately, due to a lack of appropriations from Harrisburg, construction work on the site came to a halt in the winter of 1923. Grafly and the Piccirillis continued working, however, to their own financial detriment. In the spring of 1925, Governor Gifford Pinchot allocated the final expenditures on the memorial, and after a two-year delay, work resumed. Ultimately the price tag on the Meade Memorial reached $400,000, paid for entirely by state funds.

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]inally, on the afternoon of October 19, 1927, after 16 years of planning, thousands gathered for the unveiling of the Meade Memorial. Cool, rainy weather gripped the nation’s capital on dedication day but did not dampen the spectacle, which had been planned for months. In a twist of historic irony, the executive officer charged with overseeing much of the ceremony’s logistics was none other than Ulysses S. Grant III. The grandson of the Civil War general, Grant III served as director of the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, overseeing all public parks in the district, including the Meade Memorial. A host of dignitaries, including Pennsylvania Governor John Fisher, 29 of Meade’s descendants, and several hundred war veterans were among the day’s honored guests.

Two large white sheets covered the memorial and flags reading “Battle of Gettysburg” and “Major General Meade” hung from steel wires that secured the curtains enveloping the memorial. Wreaths with the names of Meade’s corps commanders adorned the posts along the speaker’s platform. Grant escorted Henrietta Meade, the general’s daughter and only living child, to the front of the memorial. She pulled the cord, releasing the white sheets, and the Meade Memorial emerged into full view. As attendees enjoyed the sight, President Calvin Coolidge accepted the memorial on behalf of the U.S. government and offered a tribute. Though Meade had once been criticized for being too cautious in his pursuit of Lee after Gettysburg, Coolidge lauded the general’s leadership, noting, “He did not engage himself in leading hopeless charges.” The president closed with the acclaim, “through all of this shines his own immortal fame.”

Meade’s Champion

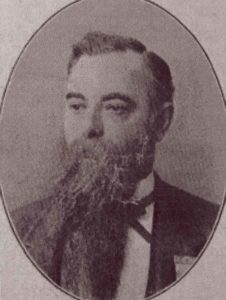

John Wesley Frazier, the active member of the Philadelphia Brigade Association and irascible, tireless leader of the fight for the Meade Memorial, had a relatively short wartime service. Frazier was a 24-year-old carpenter when he enlisted in the 1st California Regiment on April 16, 1861, as a sergeant. The regiment was one of four units composed of Philadelphia-area residents but credited to California and commanded by Oregon Senator Edward Baker in order to have the West Coast represented in what was supposed to be a short war. Frazier’s service record at the National Archives indicates he was honorably discharged at Maryland’s Camp Observation on October 12, 1861, due to “debility resulting from confluent small pox,” so he missed the October 21 Ball’s Bluff debacle in which his brigade participated and Baker was killed. After that, the 1st California was renamed the 71st Penn-sylvania, and the other Keystone State regiments were renumbered as the 69th, 72nd, and 106th regiments. Collectively, they were referred to as the Philadelphia Brigade.

Frazier rejoined the military on June 17, 1863, when he mustered in to the 20th Pennsylvania Emergency Militia, quickly organized at Harrisburg to help repel the Army of Northern Virginia’s invasion of Pennsylvania. Frazier mustered out August 1, 1863, without seeing battle, but according to his service record, not before he lost his canteen and haversack. The Philadelphian became prominent during the postwar years as a businessman and member of the Grand Army of the Republic, and with his wife, Anna, had six children. On a pension form requesting a list of spouses and any former marriages or divorces, he wrote, “My wife was not married before her marriage to me. We lived too happily together for more than 50 years to even think for a moment of divorce. It gives me pleasure to record it.” Anna Frazier passed away in 1911, and John Frazier died on September 17, 1918, well before the monument to General Meade was erected in Washington. –Melissa A. Winn

Establishing Meade’s commemorative footprint also served as an opportunity to solidify Gettysburg as the decisive battle of the war. “There was no other battle fought, or victory won during the Civil War from 1861-1865 comparable to the Battle of Gettysburg,” stated one commissioner. Offered another individual: “It is very fitting that this illustrious general should have a proper memorial erected to his honor for the heroic deeds done at Gettysburg which saved the Union.” Governor Fisher declared Meade the “triumphant commander in one of the decisive conflicts of all time.”

Debates over mentioning Gettysburg on the memorial had surfaced during construction. Pennsylvanians recommended including a quote from Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys, a division commander at Gettysburg, that reaffirmed Meade’s decisive leadership during the battle. “Meade at Gettysburg had a more difficult task than Wellington at Waterloo, and performed it equally well,” Humphreys asserted.

Another considered inscription read: “By the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to Major General George Gordon Meade who on native soil at Gettysburg in 1863 in mighty battle directed the Union Army that swept back the tide of Confederate invasion and assured the triumph of Human Freedom and National Unity.”

But, believing that “fewer words are the better,” the Commission maintained that because Gettysburg was “so great an event in the history of the Union…., any words of explanation are unnecessary.” Grafly agreed with this assessment. Simultaneously, adherence to precedence set with the Grant Memorial proved a determining factor, and the views of the Commission of Fine Arts prevailed. Since the Grant Memorial stands with a single word, “Grant,” so too would the Meade Memorial, etched simply with “Meade.”

The Meade Memorial is unique for Civil War commemoration. Most generals are honored with equestrian memorials, as seen in the portrayals of Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan. But Grafly offers an allegorical interpretation of General Meade, standing, and surrounded by six figures that represent qualities he demonstrated: military courage, energy, fame, loyalty, chivalry and progress, and war. The general stands uniformed, but without his hat. Above Meade’s head is a gold wreath and garland. He is positioned stepping forward from the cloak of battle, ready to embrace the future of peace.

One reporter reflected on the stunning sculpture and its fitting location writing, “Within the Botanic Garden grounds, close to Pennsylvania Avenue, where once his conquering army marched, the graven image of its chief will look for all time o’er the land he helped make indivisible.”

[dropcap]G[/dropcap]eneral Meade held his commemorative place on Pennsylvania Avenue for nearly four decades before being temporarily erased. During the 1960s, as events escalated in southeast Asia and domestic turmoil increased, the Civil War faded into distant memory and public interest in the leaders responsible for Union victory waned. Meanwhile, in Washington, modernization of the eastern end of the Mall’s landscape, specifically the creation of a large reflecting pool atop the I-395 underpass, forced the removal of the Meade Memorial.

On November 1, 1966, the National Park Service, the organization now responsible for management of the structures on the mall, signed an agreement providing for the removal and storage of the memorial until a “suitable location” could be found for it. The removal of the Meade Memorial, with no apparent plans for its relocation, raised the ire of Dorothy Grafly, daughter of the memorial’s sculptor. She expressed frustration that Pennsylvania officials were not consulted in the decision and noted concern about the structure’s dismantling. By the spring of 1967, the National Capitol Planning Commission and the Commission of Fine Arts had approved Meade’s new location, located slightly west of his original position.

Consequently, with beautification projects underway in 1969 workers disassembled the Meade Memorial. Contractors first cut and removed the wings from “War,” and then proceeded to disassemble the allegorical figures, then the general and the benches. Relocation did not occur immediately, however. The general sat in storage for 15 years. These years proved unkind; one observer noted that Meade sat “among weeds, unprotected, uncrated, and vandalized.” The general’s statue suffered a broken nose and lost fingers. Sometime during the years of storage the five-foot gilded wreath had been removed, or stolen.

Finally, on October 3, 1984, to considerably less fanfare and pageantry, the Meade Memorial was rededicated in a smaller plaza northwest of the original site, without the original wreath, which has not yet been located. Several years later, Walker Hancock, who had assisted Grafly in the original casting of the Meade Memorial, offered his services to cast a replacement wreath.

By the late 1980s, the fully restored memorial had resumed its place along Pennsylvania Avenue, still under Grant’s watchful eye. After a 16-year ordeal George Gordon Meade had again rightfully earned his place in the pantheon of Federal generals in the nation’s capital. Meade stood for the Union when it was “darkened by the smoke of battle, and her preservation as a Union hung upon the chance of conflict.” That history deserves to be perpetually commemorated.

Jennifer M. Murray is an assistant professor of history at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise, and the author of On A Great Battlefield: The Making, Management, and Memory of Gettysburg National Military Park, 1933-2013. She is currently working on a biography of George Gordon Meade.