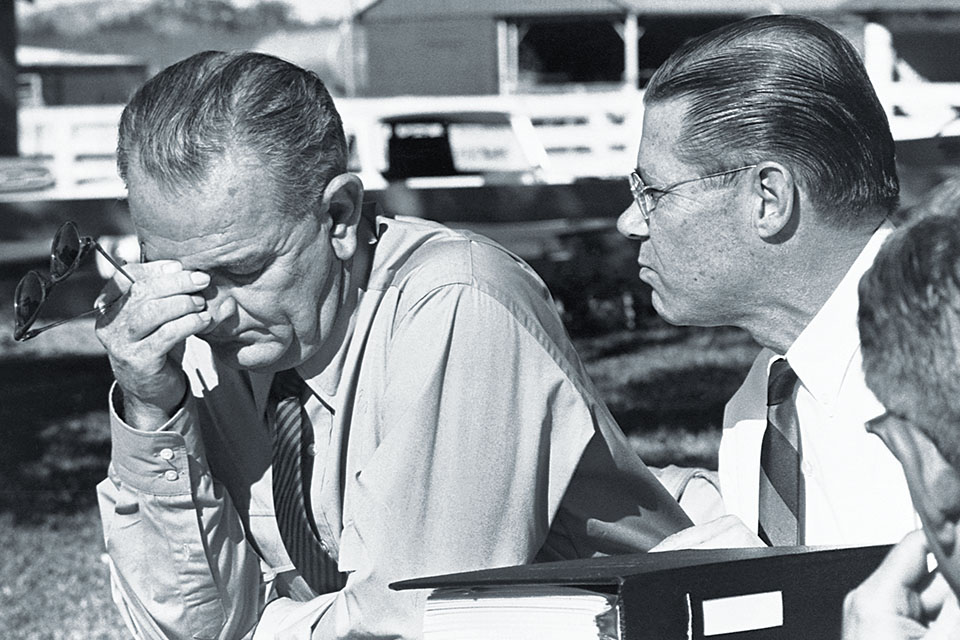

In 1966, with American involvement in the Vietnam War rapidly escalating, President Lyndon B. Johnson faced a big problem: How could the U.S. military round up enough men to send to war? Johnson could have moved to revoke student deferments, but in so doing he would have heaped lots of political misery on himself and put his administration at sharp odds with powerful lawmakers, who were writing a new Selective Service statute that would continue to guarantee 2-S deferments to undergraduate college students in good standing. He could also have chosen to draw on the million or so men and women in the National Guard and Reserves. But LBJ and his advisers knew that this course of action would be just as unpopular politically.

Johnson’s secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, had another idea: to dramatically widen the pool of draft-eligible Americans by lowering the standards for entry into the armed forces. There were plenty of young people out there who weren’t protected by student deferments but had flunked the military’s entrance exam, the Armed Forces Qualification Test. If the standards for passing the test could be lowered, McNamara argued, tens of thousands of previously “unqualified” young men and women would suddenly be available for military service.

In August 1966, McNamara went before the annual convention of Veterans of Foreign Wars to unveil his plan, promising that it would “salvage” some 40,000 draft rejects and substandard volunteers—most of them from “poverty-encrusted backgrounds”—in the ensuing 10 months. “Currently,” McNamara noted, “the military rejects 600,000 young men a year for failure to meet minimum standards.”

In his VFW speech at the New York Hilton Hotel, McNamara framed the plan as a compassionate rescue mission. Disadvantaged youths—many from urban slums and rural backwaters—would, he said, be lifted out of poverty and ignorance. They would be taught basic skills, including reading and arithmetic. Though the men may have failed these subjects in school, they wouldn’t fail now because the military was, as he put it, “the world’s greatest educator of skilled manpower.” It knew how to motivate men and deploy an impressive array of pedagogical gadgetry.

McNamara had made a name for himself as one of the “Whiz Kids” who helped to rebuild Ford Motor Company after World War II. He believed that the military could raise the intelligence of those it might otherwise reject through the use of videotapes and closed-circuit TV lessons. “A low-aptitude student,” he said, “can use videotapes as an aid to his formal instruction and end by becoming as proficient as a high-aptitude student.”

‘Second-class fellows’ recruited

McNamara’s announcement apparently caught the Pentagon by surprise, as the plan was clearly a dramatically expanded version of a proposed three-year, $16.4 million experiment—the Special Training Enlistment Program (STEP)—that Congress had killed the previous year. Nonetheless, Project 100,000—named for its target first-fiscal-year recruitment level—was officially launched on October 1, 1966. By the end of the war, it would bring 354,000 “second-class fellows”—as President Johnson had referred to its recruits in private—into the armed forces.

In announcing Project 100,000, McNamara didn’t say anything about combat duty. He said the participants would gain valuable skills and self-confidence, which would help them get good-paying civilian jobs when they got out of the service. To hear him describe it, one would have thought the men were going off to school, not to war.

From nearly the beginning of Project 100,000, McNamara’s critics accused him of disguising its true objective: using the poor instead of the middle class for combat in Vietnam. The truth was more complex. McNamara had proposed Project 100,000 two years earlier, seeing it as a way to contribute to the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty. In fact, the idea had been kicking around Washington before McNamara arrived on the scene.

Idea floated by Moynihan

Its leading advocate was Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a sociologist who in 1976 would be elected to the U.S. Senate from New York. The best way to alleviate poverty in America, Moynihan’s argument went, would be to draft the hundreds of thousands of young men and women being rejected annually as unfit for military service. Take these young men—mostly inner-city Blacks and poor, rural whites—and put them into uniform. Instill discipline. Train them to bathe daily, salute, and take orders. Teach them a marketable skill. After a couple of years, lazy, unmotivated slackers would be transformed into hard-working, law-abiding citizens. Moreover, the new generation of military recruits could then teach their children to be solid middle-class citizens, thus breaking the generation-to-generation continuity of poverty.

Johnson and McNamara embraced Moynihan’s concept in 1964, two years before Project 100,000 was launched. Secret White House recordings captured a conversation in which Johnson said that he wished the military could be persuaded to take the “second-class fellow,” adding: “We’ll…teach him to get up at daylight and work till dark and shave and bathe.…And when we turn him out, we’ll have him prepared at least to drive a truck or bakery wagon or stand at a gate [as a guard].”

McNamara told LBJ that uniformed officers in the Defense Department were opposed to drafting such men because “they don’t want to be in the business of dealing with ‘morons.’ They call these ‘moron camps’ now, inside the [Pentagon]. The army doesn’t want to be thought of as a rehabilitation agency.”

In 1964 and 1965, Johnson and McNamara had tried repeatedly to lower the bar for military service, only to be stymied by higher-ups at the Pentagon and their allies in Congress. Democrat Richard Russell of Georgia, the powerful chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee and LBJ’s mentor on Capitol Hill, accused McNamara of trying to set up a “moron corps.” The Department of the Army was more temperate in its criticism, saying only that it wanted to “fight with the highest caliber of men available.”

Military leaders reluctantly agree

By 1966, however, the top brass, desperate for manpower, had to capitulate: If Johnson and McNamara weren’t willing to draft more middle-class Americans, then “second-class” servicemen would have to suffice. With bitter disappointment and grave doubts, military leaders went along with the decision of their civilian bosses, and Project 100,000 became a reality.

Military recruiters, backed by an aggressive public relations campaign (one army ad in Hot Rod Magazine proclaimed, “Vietnam: Hot, Wet, and Muddy—Here’s the Place to Make a Man!”), had great success persuading men from poor urban neighborhoods to join Project 100,000. Glossy brochures with exotic locations and glamorous jobs portrayed the military—even with a war going at full tilt—as a good career choice. The pressure on recruiters to sign up more “volunteers” for the program was intense. Many resorted to using “ringers” to take tests to gain a passing score for enough recruits to meet quotas.

Typically, military recruiters would get the names of low–scoring men who were now acceptable to the armed forces and visit them to steer them toward three-year hitches. The recruiters would tell them that if they waited for the draft, they would serve only two years but almost certainly end up in an infantry platoon in Vietnam. But if they signed up for three years, they would be assigned to a noncombat job. There was, however, an important catch: The military didn’t have to honor any oral promise made by a recruiter. A recruiter might promise prospects a job like helicopter maintenance, but after basic training—when it was time to go to a specialized school—the military could decide that their test scores weren’t high enough to qualify for helicopter maintenance. Or if they did qualify but flunked the training, they could be transferred to infantry. Thousands of three-year Project 100,000 “volunteers” ended up in infantry this way.

recruits disproportionately die

Project 100,000 recruits—“New Standards” men, they were called—were assigned to all major branches of the armed forces: 71 percent to the army, 10 percent to the marine corps, 10 percent to the navy, and 9 percent to the air force.

Most of the 354,000 men and women brought into military service through Project 100,000 went to Vietnam, and about half of those who went to Vietnam were assigned to combat units. All told, 5,478 of them died while in the military, most of them in combat. Their fatality rate was three times that of other GIs.

Project 100,000 men had to complete basic training, and, in some cases, undergo additional training. Novelist Larry Heinemann, who had served with the 25th Infantry Division in Vietnam, recalled in a 2005 memoir that in his basic training barracks at Fort Polk, Louisiana, he would look across the street and watch McNamara’s Boys in a special training company. “These were the guys who could not hack it during regular basic training,” he wrote. “It was painful to watch.…Some of them could not even get the hang of so simple a thing as standing at attention, and otherwise seemed severely unsuited for military life.”

“The young men of Project 100,000 couldn’t read,” Joseph Galloway, a war correspondent who was awarded a Bronze Star with Valor in Vietnam for carrying wounded men to safety in the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley, later recalled. “They had to be taught to tie their boots. They often failed [basic training] and were recycled over and over until they finally reached some low standard and were declared trained and ready. They could not be taught any more demanding job than trigger-pulling, [so most of them] went straight into combat, where the learning curve is steep and deadly.”

One veteran who had good reason to be dismayed by the deaths of Project 100,000 men in Vietnam was Leslie John Shellhase, who had been wounded in the Battle of the Bulge in World War II and had served as a lieutenant colonel under McNamara on a planning team at the Pentagon in the 1960s. “We resisted Project 100,000 because we knew that wars are not won by using marginal manpower as cannon fodder, but rather by risking, and sometimes losing, the flower of a nation’s youth.” He and other Pentagon planners tried to persuade McNamara to drop Project 100,000. When that failed, they proposed altering the program so that military commanders would be barred from sending low-aptitude men into danger zones. “We never envisioned that these men would be used in combat,” he said. “Instead, we intended for them to be used in service and support areas, where their mental limitations would not cause them to be killed.” Unfortunately, Shellhase and his fellow officers failed in their effort to keep Project 100,000 men off the battlefield.

‘His death almost destroyed us’

Barry Romo saw a lot of combat in Vietnam as an infantry platoon leader in 1967–1968, receiving a Bronze Star for his courage on the battlefield. During his tour, he learned that his nephew Robert, just a month younger than him, had been drafted and was being trained at Fort Lewis, Washington, to be an infantryman, destined for Vietnam. Barry was alarmed because he knew that Robert had failed the Army’s mental test. But Project 100,000 had lowered the standards, making him eligible to serve. A host of people—his relatives, his comrades at Fort Lewis, his sergeants, his officers—wrote to the commanding general at Fort Lewis, asking that Robert not be sent into combat because, as one relative put it, “he would die.”

But the general turned down the request, and when Robert arrived in Vietnam he was sent to an infantry unit near the border of North Vietnam—one of the most dangerous combat areas. During a patrol, he was shot in the neck while trying to help a wounded friend and died.

In a speech delivered 42 years later, Barry Romo said that the family had never recovered from losing Robert. “His death,” he said, “almost destroyed us with anger and sorrow.”

Military leaders—from William Westmoreland, the commanding general in Vietnam, to lieutenants and sergeants at the platoon level—viewed McNamara’s program as a disaster. Project 100,000 men were typically slow learners, so they had difficulty absorbing training. And because many of them were incompetent in combat, they endangered not only themselves but their comrades as well.

“Project 100,000 was implemented to produce more grunts for the killing fields of Vietnam,” wrote Col. David Hackworth, who fought in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars and became one of the most highly decorated warriors in American history. “It took unfit recruits from the bottom of the barrel and rushed them to Vietnam. The result was human applesauce.”

McNamara’s intentions to use video instruction to raise the intelligence levels of Project 100,000 may have been sincere, but few men actually received it. There was a bloody war raging, and Army and Marine units in Vietnam desperately needed replacements. Training centers were under great pressure to get troops to Vietnam as quickly as possible. There was no time for remedial reading and arithmetic.

Westmoreland estimated that, in fact, only about 10 percent of McNamara’s Boys could be molded into real soldiers. Although some Project 100,000 men did well in the service—passing basic training and going on to productive military assignments—large numbers of them had trouble coping with the demands of military life. They were often hazed, ridiculed, and demeaned. Ironically, McNamara, in one of his speeches extolling Project 100,000, had said, “I have directed that these men shall never be singled out or stigmatized in any manner.”

Many discharged ‘other than honorable’

When it was time for Project 100,000 men to leave the military, many of them received a heavy blow. Slightly over half of them—180,000—were separated with discharges “under conditions other than honorable,” a stigma that made it hard to get good jobs because many employers would not hire veterans who failed to produce a certificate of honorable discharge. They were often barred from veterans’ benefits such as health care, housing assistance, and employment counseling. Some of them became chronically homeless and troubled.

Although some “bad-paper” vets had been guilty of serious offenses, most had been accused of minor offenses related to the stresses of military life and combat: AWOL, missing duty, abusing alcohol or drugs, or talking back to a superior. David Addlestone, the director of the National Veterans Law Center from its founding in 1978 until his retirement in 2005, said that one of the leading reasons that the military gave for bad-paper discharges for Project 100,000 men was “unsuitability.” Little wonder: Many of the men were obviously unsuitable to be drafted in the first place.

In their 1978 book, Chance and Circumstance: The Draft, the War, and the Vietnam Generation, Lawrence M. Baskir and William A. Strauss, who were senior officials on President Gerald Ford’s Clemency Board, told of Gus Peters, who “came from a broken home, dropped out of school after the eighth grade, and was unemployed for most of his teenage years. His IQ was only 62.…His physical condition was no better.” Drafted under Project 100,000, Peters was ridiculed by other soldiers, and he failed basic training. Unable to cope with military life, he went AWOL and was eventually given an undesirable discharge. Baskir and Strauss concluded that Peters was worse off when he left the service than when he had entered it. “He still had no skills and no useful job experience,” they wrote, “and he now was officially branded a misfit.”

There was a cruel irony in the less-than-honorable discharges. Millions of men who beat the draft through deferments and exemptions suffered nothing. In fact, they held an advantage over men who served: They got first crack at jobs and compiled seniority and experience. Even the draft dodgers who fled to Canada and Sweden got an amnesty. But not McNamara’s bad-paper vets. They had no one to lobby for them.

In his starry-eyed belief that videotapes could dramatically transform slow learners, McNamara revealed the same blind faith that deluded him into thinking that he could defeat the enemy in Vietnam by using computers, statistical analyses, and advanced technology. As biographer Deborah Shapley put it, McNamara was “a naive believer in technological miracles.”

At the beginning of his program, McNamara had predicted that after returning to civilian life, Project 100,000 men would have an earning capacity “two to three times what it would have been if there had been no such program.” But a follow-up study on Project 100,000 men showed that in the 1986–1987 labor market, they were “either no better off or actually worse off” than nonveterans of similar aptitude.

Many veterans of Project 100,000 were psychologically devastated by the war. John Wilson, a psychologist at Cleveland State University who spent several years studying Vietnam veterans’ emotional problems, estimated that thousands of Project 100,000 men who had served in Southeast Asia were so “severely messed up” that they couldn’t function in society—hold jobs, raise families, and cope with day-to-day living.

Project 100,000 called ‘a disaster’

Historians have also rendered harsh verdicts of Project 100,000. In his 1993 book, Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam, Christian G. Appy of the University of Massachusetts wrote that while the program “was instituted with high-minded rhetoric about offering the poor an opportunity to serve,” its result “was to send many poor, terribly confused, and woefully undereducated boys to risk death in Vietnam.” Anni P. Baker, a history professor at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, has branded Project 100,000 “a disaster, benefiting neither the men nor the Armed Forces.” In 1993 Jacob Heilbrunn, then a fellow at Georgetown University, wrote in the New Republic that “McNamara’s experiment in social engineering had the most awful results,” including ridicule in training camps and death in Vietnam. And the late Samuel F. Yette, a professor at Howard University, said that instead of preparing impoverished young men with skills for a better life, Project 100,000 was “little more than an express vehicle to Vietnam.”

Toward the end of his life, McNamara issued a series of candid mea culpas for misjudgments about Vietnam that were made during his tenure at the Pentagon (1961 to 1968), especially his delay in acting on growing doubts that the war could be won. “I’m very sorry that in the process of accomplishing things, I’ve made errors,” McNamara told filmmaker Errol Morris for The Fog of War, Morris’s Oscar-winning 2003 documentary.

While he never issued a formal apology for his role in the Vietnam quagmire, McNamara, who died in July 2009 at age 93, made clear he was haunted by the blunders made under his watch that cost the lives of thousands of U.S. troops. “People don’t want to admit they made mistakes,” he explained in 2003 to a reporter for the New York Times. “This is true of the Catholic Church, it’s true of companies, it’s true of nongovernmental organizations, and it’s certainly true of political bodies.”

Conspicuously absent from McNamara’s apologias was Project 100,000, which officially ended on December 31, 1971. To the very end of his life, McNamara refused to acknowledge the many accounts of abuse, suffering, and death associated with Project 100,000. Selectively looking at the success stories of some Project 100,000 men who did well, he insisted that the program had been beneficial. He was resentful of the term “McNamara’s Moron Corps,” which he had heard for years.

Nonetheless, Project 100,000 and other Vietnam-era failures wrecked McNamara’s reputation. “At first admired for his intelligence and analytical prowess, he later became one of the most hated men in America by the officers and enlisted personnel he had led,” Thomas Sticht wrote of McNamara in the 2012 anthology, Scraping the Barrel: The Military Use of Substandard Manpower, 1860–1960. One officer even confronted McNamara in public. As McNamara touted the virtues of Project 100,000 at a Washington conference, an Army psychologist who was treating psychologically afflicted Vietnam veterans at Walter Reed Army Medical Center stood up and spoke out. Although he was a “mere” captain, Dr. Walter P. Knake told McNamara, “What you are doing is wrong!”

Regardless of culpability, the results of the project—not its intentions—doomed McNamara’s Boys, who were, on average, just 20 years old and disproportionately Black. “They never got the training that military service seemed to promise,” Baskir and Strauss concluded. “They were the last to be promoted and the first to be sent to Vietnam. They saw more than their share of combat and got more than their share of bad discharges. Many ended up with greater difficulties in civilian society than when they started. For them, it was an ironic and tragic conclusion to a program that promised special treatment and a brighter future, and denied both.” MHQ

Hamilton Gregory, who served in Army Intelligence in Vietnam in 1968–1969, is the author of McNamara’s Folly: The Use of Low-IQ Troops in the Vietnam War.

This article first appeared in the spring 2017 issue (Vol. 29, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline ‘McNamara’s Boys.’