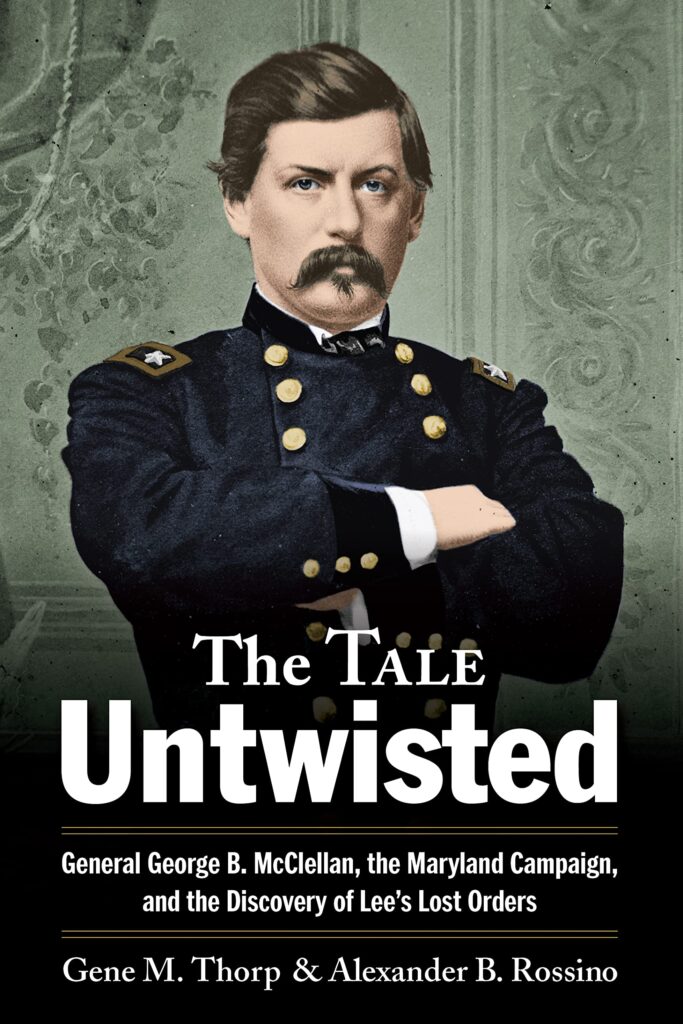

It is impossible to separate Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s legacy from Special Orders No. 191, Robert E. Lee’s so-called “Lost Orders” found by Union soldiers in a field near Frederick, Md., during the September 1862 Maryland Campaign. For the remainder of his life, McClellan was unable to negate the reigning argument that he had acted with undue hesitancy after learning of Lee’s campaign intentions on September 13, and despite Union triumphs at South Mountain and Antietam in the coming days, “Little Mac” allowed Lee’s battered army to escape back to Virginia, prolonging the war for another 2½ years. That belief has prevailed for more than a century. Thankfully, a new study by Gene M. Thorp and Alexander B. Rossino (The Tale Untwisted, Savas Beatie) explores the controversy’s deepest roots, painting a compelling picture of what truly occurred in those critical weeks in the late summer of 1862.

As you point out in your book, debate about the “Lost Orders” typically alternates between the arguments put forward by authors Stephen Sears and Joseph Harsh. For those perhaps unfamiliar with Special Orders No. 191, can you provide more detail on what was at stake on September 13, 1862?

Gene Thorp – I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that the existence of the country was in the balance. Confederate forces on September 13 were advancing northward on a thousand-mile front, from Mississippi to Maryland. Confronting McClellan, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had decisively defeated Union troops two weeks earlier at the gates of Washington at the Second Battle of Manassas. The Confederates were now advancing through western Maryland virtually unopposed, with almost nothing to stop them from marching on to Baltimore or into Pennsylvania.

At the same time, the Union armies in the area were wrecked. Federal casualties had been tremendous, their supplies had been burned, and the soldiers were famished, one of whom summed up, “We had been starved till we were sick and brutish; we were chafed and raw from lice and rough clothing; we were foot sore and lame; there was hardly a man of us who was not afflicted with the diarrhoea.” Simultaneously, regiments of completely untrained Federal recruits poured into the capital from the other side, adding to the confusion.

In just two weeks, with skill and determination, McClellan had cobbled together enough men and supplies to march a respectable army out of Washington to challenge Lee. Positive as the Army of the Potomac’s transition was, McClellan still needed some sort of break to give him a strategic advantage over Lee, for a defeat of the Federal army at this moment would leave the capital practically defenseless and vulnerable to capture.

Unknown to McClellan as he marched into Frederick the morning of September 13, that break was happening only a mile or so away. A soldier of his army had just stumbled upon a misplaced order from Lee which, although a few days old, revealed that the Rebel army had divided into five parts to surround and capture a Union garrison in Harpers Ferry that ran astride Lee’s planned supply route. When this order came to McClellan’s hands, a brief opportunity opened for him to strike a decisive blow against the rebellion. The question has become, did McClellan do everything that could be reasonably expected of him to capitalize on this find?

Alexander Rossino – In addition to the issues summarized by Gene, Lee had also set in motion a two-step plan to capture the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry and then reassemble his army west of the Blue Ridge Mountains, known in Maryland as South Mountain, for a decisive clash with the pursuing Army of the Potomac. Outlining this plan in Special Orders No. 191, Lee intended to break the enemy, which he assumed was demoralized and disorganized after the rout at Second Manassas, as far from Washington, D.C., as possible. To Lee’s dismay in late August, he had been unable to pursue and eliminate the remnants of John Pope’s Union Army of Virginia when those men found refuge in the fortifications surrounding the capital city.Now, he hoped to achieve the decisive Napoleonic-style victory which had eluded him to that point. To that end, Lee set a trap for McClellan by planning to engage him on favorable ground along Beaver Creek five miles north of Boonsboro, Md. McClellan did not know this, of course, but he avoided it anyway by rapidly advancing from Frederick after reading the Lost Orders. This completely disrupted Lee’s plan, forcing him to fight costly battles at the South Mountain passes, and inflicting serious casualties on the Army of Northern Virginia when Lee was least prepared.

What inspired you to write this book? Was it more important to present a defense of McClellan’s response to the discovery of the Lost Orders or to provide a more thorough examination of their ultimate impact on the Maryland Campaign and the Battle of Antietam itself?

GT – The genesis of this book began back in 1999 when I started a detailed day-by-day atlas of the Antietam Campaign. When creating the base maps and plotting out the troop movements I was shocked by how little they reflected what I had previously read and seen in histories on the topic. One item in particular that stuck out to me was how much activity there was in the Union army the day Lee’s orders were found and delivered to McClellan. Everything mainstream I had read up to that point had given me the impression that the Union army was mostly stationary around Frederick the entire day while McClellan “dawdled.” When I read McClellan’s so-called “Trophies” telegram in context with all the other orders and movements I had plotted, a noon sending of the message no longer made sense. I thought the timestamp was wrong but wanted more evidence to prove it.

Fast forward a few years and I stumbled upon Maurice D’Aoust’s discovery of Lincoln’s copy of the same telegram, but the sent timestamp was midnight instead of noon. On September 7, 2012, I published the second of two op-ed pieces in The Washington Post, which argued that the Trophies telegram was actually sent at midnight and that McClellan did not delay in marching his troops after Lee. Noted author Stephen Sears took issue with my article, and a spirited public debate ensued between us, which I encourage your audience to read.

Many years later, Alex, who had written the book Six Days in September, approached me with an offer to team up and publish a detailed study based on the new research we had acquired about McClellan’s actions on September 13, the day he received Lee’s Lost Orders. We published the study in a digital-only format through Savas Beatie but in the end felt that our readers wanted more context.

With the support of Savas Beatie, this new expanded print version of the book does just that, but in the process, we needed also to broach other issues like McClellan’s supposed “case of the slows,” his role in the surrender of Union General Dixon Miles’ Harpers Ferry garrison, and the political undercurrents of the time. So, although the book is primarily to prove that McClellan acted appropriately after receiving the Lost Orders, it inevitably tackles many other misunderstandings and misinformation about the Antietam Campaign. More books from us will be forthcoming.

AR – Gene’s research told a story about these events that I had not read anywhere else. I had done my own digging into the subject of McClellan’s advance from Washington to Frederick and had begun to suspect that the received history was incorrect, but I had no idea just how incorrect it was until Gene and I began huddling on the subject. It became clear to me that we needed to publish something on the topic because the errors printed decades earlier still held sway.

Many observers are quick to point out what they believe McClellan did wrong in the Maryland Campaign. But under the circumstances he faced in assuming command as he did on September 2, what did he do right?

GT – In my opinion, McClellan did everything that could be expected of a commander placed in a similar situation. He had already gained the trust of his soldiers during the Peninsula Campaign, so when he resumed command after Pope’s decisive defeat at Second Manassas, his men were ready to follow him. To secure the capital, rebuild confidence, and resupply his men, McClellan quickly brought them into defensive positions around Washington they were familiar with.

Having anticipated that after Second Manassas that Lee would invade Maryland and try to attack the capital from the northwest where the defenses were weaker, McClellan proactively moved large numbers of Union troops (the 2nd, 12th, and a division of the 4th Corps) without any rest or resupply across the Potomac to cover those approaches to Washington. The moment McClellan suspected the bulk of Lee’s army was in Maryland, about September 6, he immediately moved another sizable force (the 1st, 6th, 9th, and a division of the 5th Corps) across the Potomac to join those already there, while at the same time he integrated raw and untrained regiments into the veteran commands. Immediately afterward, and without any delay, he pushed the troops he then commanded in the field out toward where he suspected Lee’s army was.

McClellan’s advance was so aggressive and efficient that by the time the Lost Orders came into his hands on September 13, his army was already close on Lee’s heels and able to strike such a powerful blow the next day at South Mountain that Lee’s army was forced to flee under the cover of darkness. Overall, McClellan’s acknowledged organizational skills never shined brighter than in the two weeks following Second Manassas.

AR – I’d like to turn the question on its head and ask, after reading our research, what did McClellan do wrong? We need to remember that the received narrative for more than a century has been written from the perspective of the Radical Republicans and Lincoln enthusiasts—men who loathed George McClellan. In other words, they proffered a biased and misleading perspective from the start. All we’re doing is correcting the record. Looking at the subject purely from the military perspective, the handed-down claims of McClellan’s timidity, slow marching, and overcautiousness up to September 15 fall flat. Whatever one thinks of his performance at Antietam [on September 17], it is difficult to ignore the success that Little Mac had until that date.

How great a factor was the Union army’s absence of cavalry for several days early in the campaign on McClellan’s fortunes? This seems a very much overlooked obstacle he faced.

GT – Few people seem to be aware that McClellan started the campaign almost entirely devoid of cavalry. Pope’s horsemen had been rendered useless for offensive and scouting operations after Second Manassas, while most of McClellan’s cavalry were still in transit from the [Virginia] Peninsula, being the last to be shipped of his army since horses required a considerable amount of room and special handling. Critics of McClellan should consider that his army had virtually no “eyes” for the first week of the Antietam Campaign and had to rely almost entirely on rumors from the front that came to Washington by telegraph while the lines remained open. You can imagine how this slowed McClellan’s initial advance when he had no way to scout ahead of his columns or locate the exact position of the Confederate front lines.

AR – I’ve come to think that the lack of Federal cavalry may have actually helped McClellan by lulling General Lee into a false sense of security. We need to remember that at the outset of the Maryland operation, Lee believed his army was “strong enough to detain the enemy upon the northern frontier until the approach of winter should render his advance into Virginia difficult, if not impracticable.” This means Lee assumed he could keep the enemy detained in Maryland and/or Pennsylvania until December. Federal cavalry not pressing [J.E.B.] Stuart in any real strength meant the cavalier reported only limited contact with the enemy. In other words, it was all quiet on the eastern front. Then, suddenly, Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis on September 8 that a strong column had begun making its way toward him. The weeks and months Lee thought he had to operate had vanished. He would need to fight again and much sooner than anticipated.

The criticism typically leveled at McClellan as having “the Slows” in his pursuit of Lee—citing marches only 6-8 miles per day as “clear” evidence of that—you stress in your book that it simply wasn’t true. Explain.

GT – The first question any objective reader needs to ask regarding this charge against McClellan is how do you calculate how many miles an army marched in a day? With any army, one part might be stationary to present a bold front to the enemy or hold a strategic point, while the other parts move aggressively in the rear and the flanks. Does one measure the distance marched for each column, then calculate the average between them all? What if each column is a different size? Are the average distances then also weighted by the number of men in each column? What about units that joined the army mid-campaign? How is their daily march counted into the whole?

The “six-miles-a-day” comment comes from [General-in-Chief] Henry Halleck, who apparently counted only the movements of McClellan’s center column consisting of the 2nd and 12th Corps on September 7–10, who marched slowly out of necessity to allow the rest of the army to cross the Potomac to come up on their flanks. Ignored are the severe marches of 32–41 miles previously made by that same column in the days after Second Manassas. Also ignored are the forced marches made by nine new regiments, about 8,000 men, who were assigned to the 2nd or 12th Corps on September 7 and rapidly marched 34 miles from Washington up the crowded Rockville Pike to catch their veteran brethren on the front. Additional “green” regiments made similar forced marches at different times during the campaign to catch the 1st, 4th, 6th, and 9th corps. Halleck also appears to have completely discounted the progress of [Generals] William Franklin’s and Ambrose Burnside’s Wings, who during the same time marched 33 to 41 miles from the Virginia side of the Potomac to positions on either flank of the center column.

Ultimately, the real question for historians is, did McClellan move fast enough? Considering the extreme logistical and morale issues he was handed; our research shows that he did.

AR – The claim is easily disproven slander. The evidence suggests that McClellan’s advance in earnest, beginning on September 8-9, took Lee by surprise. That news, along with word that the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry remained in place, forced Lee to design Special Orders No. 191, and to get his army moving. Remember Lee’s statement about detaining the enemy on the northern frontier until winter? McClellan’s advance dispelled that delusion suddenly and decisively. Even before September 13, George McClellan moved more rapidly than Robert E. Lee found convenient.

Did McClellan, as the journalist William Swinton would claim, recklessly choose to ignore the fate of the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry?

GT – Absolutely not. The garrison belonged to Maj. Gen. John E. Wool of the Middle Department’s 8th Corps and not to George McClellan. Wool, who also outranked McClellan, reported directly to Henry Halleck. The night before the Confederates crossed into Maryland, McClellan, in person with Secretary of State William Seward, went to Halleck’s room and requested him to either withdraw the garrison through Hagerstown to aid in covering the Cumberland Valley or fall back to Maryland Heights and hold its own to the last. Halleck responded that things were fine as they were and ushered McClellan out of his room, leaving the garrison in place.

It was not until September 11 that Halleck authorized McClellan to take command of the garrison, but by that time communication with it had been cut off. Prior to this point, McClellan had borne no responsibility, officially or otherwise, for the fate of Harpers Ferry, which is a fact that critics of the general have repeatedly ignored.

AR – McClellan fretted about the safety of the garrison before and after he was placed in command of it. He then designed his strikes on the South Mountain gaps to get William Franklin’s 6th Corps into Pleasant Valley and relieve Harpers Ferry as quickly as possible. It is easy to forget that McClellan’s main effort against Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps near Boonsboro were pinning actions. With Rebel forces held in place defending those gaps, Franklin could break through at Crampton’s Gap without worrying too much about the safety of his rear once he had gotten behind Rebel lines. McClellan could then reinforce Franklin with the 2nd or 12th Corps while maintaining the pressure on Lee’s men near Boonsboro. Lee, though, withdrew west overnight, ending the opportunity for McClellan to continue his assault the next day.

Did McClellan realistically have an opportunity to prevent the fall of Harpers Ferry?

GT – If McClellan had been given the full support of his superiors and if Dixon Miles had put up any kind of competent resistance, then McClellan would then have had a reasonable chance to free the garrison there. The fact is, Halleck refused to allow McClellan any control over the garrison until after it was cut off and surrounded by Stonewall Jackson, while Miles, although he did occupy Maryland Heights, an almost impenetrable position, put up such an incompetent defense that he was driven off it.

The morning after Miles abandoned the heights, September 14, he succeeded in getting a message through to McClellan announcing that he could hold out for 48 more hours. However, only 24 hours later, with McClellan’s 6th Corps having just arrived at the northern base of Maryland Heights, Miles capitulated. Had Miles been able to maintain control of Maryland Heights, something Union commanders before and after the Antietam Campaign were easily able to do, the presence of the 6th Corps at its base on the morning of September 15 proves that McClellan could have lifted the siege.

AR – It would have been tricky, but I believe he could have done it if Miles had resisted for the full 48 hours he said he could on September 15. We don’t go into this in the book as such, but Lee withdrawing toward Sharpsburg created a conundrum for Little Mac because Elk Ridge separated his army into two parts. One of those parts faced Rebels under the command of Stonewall Jackson. The other faced Lee and James Longstreet west of the ridge.

Put yourself in Little Mac’s place for a moment. It is the early afternoon of September 15 and you are facing Lee on one flank and, potentially, Jackson on the other. It is not an enviable position. McClellan had the numbers, however, and could have pushed his army down Pleasant Valley to overwhelm the divisions of Lafayette McLaws and Richard Anderson. If he did that while beating back any attack launched by the weakened force under Lee, he could have relieved Harpers Ferry.

What was behind Dixon Miles’ decision not to reposition his force on Maryland Heights sooner, as had been recommended? You do write that Miles was out of communication with Halleck, at least, after September 11. Nevertheless…

GT – Miles did have troops on Maryland Heights, but not in a strong enough force to hold back the Confederate attack that eventually came after he was surrounded. It would appear Miles kept most of his forces in Harpers Ferry itself due to direct orders from his superior, General Wool, to that effect. When Halleck suggested to Wool on September 5 that he should order Miles to withdraw all of his force to Maryland Heights, Wool that same day ordered Miles by telegram to “be energetic and active, and defend all places to the last extremity. There must be no abandoning of a post, and shoot the first man that thinks of it, whether officer or soldier.”

Just to make sure his message was clear, Wool sent another telegram to Miles that same day: “You will not abandon Harper’s Ferry without defending it to the last extremity.” Miles, it would seem, was literally following orders. Nonetheless, Maryland Heights was the key to the defense of Harpers Ferry, and for whatever reason Miles did not make holding it a priority.

AR – This is a complicated issue that we do not cover in detail because it is out of the scope of our book. That said, I think it is too simple an approach to look at the terrain around Harpers Ferry and conclude based purely on topography that Maryland Heights is the most desirable place to relocate. The elevation of the position is not the only consideration. Other important factors must be thought about, including the critical availability of fresh water and rations. Neither of these things can be found in abundance on the heights.

Shifting the garrison meant marching 14,000 men, including thousands of horses, onto a piece of ground that is difficult in the extreme to navigate. Anyone who has been there can tell you the ground is rocky and broken. Where does Miles lodge these men? In addition, Miles faced the likelihood that as many as 2,000 contrabands would have accompanied his force to avoid capture. This raises the number of people on Maryland Heights to at least 16,000.

By comparison, the population of Frederick City at the time was only 8,000 people. I find it impossible to accept that establishing a city twice the size of Frederick on a barren peak with limited water resources, no food, and no shelter was a more viable defensive strategy than holding the lines around Harpers Ferry.

As Gene notes, Miles did defend the heights, just not with enough men to keep the Confederates from capturing the place. Had he bolstered the size of the force, maybe he could have kept McLaws at bay for long enough, yet he did not. The proper thing for Miles to have done was retire north to Pennsylvania. But again, as Gene notes, General Wool forbid him from doing this, thereby sealing the garrison’s fate.

You provide considerable evidence as well as a timeline about the “12 M” controversy—disputing the commonly accepted claim that McClellan had wired Lincoln about discovery of the Lost Orders at noon September 13 as opposed to midnight that day. Why does this controversy continue to have legs?

GT – I don’t know, but that is one thing I’d like to see changed in my lifetime. Hopefully our book and interviews like this one will encourage people to read our study and objectively examine the facts themselves. I suspect that not enough people have yet seen the overwhelming evidence that proves the telegram was sent at midnight. As more and more people read the works of authors like Steven Stotelmyer, Scott Hartwig, Tom Clemens, and Maurice D’Aoust, who also advocate that the McClellan’s “Trophies” telegram was sent at midnight, I think the correction will finally get through. After all, if the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Battle Cry of Freedom, James McPherson, insists, “If I were writing my Antietam book today, I would follow their account,” then I think we are moving in the right direction.

AR – This problem has become entrenched in the structural history of the campaign, which is what keeps it in place. It certainly does not help that even the introductory film shown to visitors at the Antietam National Battlefield offers the traditional view of McClellan—although, to be fair, I think a new film is being made to update the history.

Entrenched premises are extremely difficult to dislodge. So many authors in the past simply accepted the noon “Trophies” telegram claim that they presented it as a received “fact.” When people new to the subject start reading on the campaign, they frequently go to the work of McClellan’s detractors first. There they encounter various aspects of the “McClellan Myth,” as I like to call it, including falsehoods such as the 12 noon “Trophies” telegram. These flawed hypotheses then become the basis of their understanding.

I’d like to add that there is a desperate need for a new single volume history of the Maryland Campaign. Two volume studies, such as that published by Scott Hartwig, are great for experts in the field, but few general readers are likely going to tackle hundreds upon hundreds of pages of footnoted text. A single volume history is more accessible to most readers.

From what you document in your book, McClellan was anything but docile both before and after the discovery of the Lost Orders in the orders he sent. Why is the incredible level of communication that he issued to his commanders and Washington so readily ignored in campaign histories?

GT – I would like to know that myself. The biggest culprit has probably been group think. Historians did not want to challenge the overwhelming narrative that McClellan could do nothing right. I suspect that another major issue has been access to primary materials.

Not long ago, the only way a person could get access to the Official Records, letters, diaries, regimental histories, and newspapers of the Civil War era was to locate the few facilities which held these collections and visit each in person. The good news is that technology has changed access dramatically in the last two decades. An incredible amount of primary source material, including the McClellan papers, can now be accessed online by anyone whenever and wherever it is convenient to them, so our version of events can now be easily fact checked.

AR – Not all campaign histories ignore it. Scott Hartwig’s To Antietam Creek is a good example. It delves into the early days of the campaign and credits Little Mac more than other books had up to the time of its publication in 2012. This said, the book is also just shy of 800 pages long, so the length and depth of the information in it can be intimidating to the non-specialist. A shorter study such as The Tale Untwisted can really dial into the subject and make the argument for McClellan’s energy and efficiency in a clear and comprehensible manner to casual readers and experts alike. Sometimes, there is an advantage to brevity.

The Tale Untwisted

General George B. McClellan, the Maryland Campaign, and the Discovery of Lee’s Lost Orders

By Gene M. Thorp and Alexander B. Rossino, Savas Beatie, 2023

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

McClellan sent a separate telegram to Halleck at 11 p.m. September 13. Tell us more about the significance of that telegram.

GT – At this moment in the campaign, Halleck retained almost as many men in the Washington defenses to guard the capital as McClellan had to fight Lee’s army. McClellan’s 11 p.m. telegram proves that he was aggressively advocating to pursue Lee with all the forces he could muster, while it was Halleck who was being overcautious. Unlike earlier in the campaign when McClellan considered Halleck’s concerns about the possibility of a Confederate attack on Washington, in his 11 p.m. telegram he doubled down on his offensive strategy by arguing the value of pushing his army with the maximum force available to meet the enemy at South Mountain.

McClellan also inadvertently verified that he had received Lee’s “Lost Orders” after noon when he informed Halleck in his 11 p.m. telegram that, “An order from General R.E. Lee…has accidentally come into my hands this evening”—where evening meant afternoon in 19th-century parlance.

AR – When viewed as part of the continuum of communications between McClellan and Washington on September 13, the 11 p.m. telegram is a key piece of evidence illustrating Little Mac’s industry during the day and his knowledge that evening. In it he pushed back against Halleck’s constant whining about the safety of the capital city (it was not in danger) and he assured the skittish general-in-chief that he had the entire enemy army in front of him. The 11 p.m. telegram also supports the fact that McClellan wrote his “Trophies” telegram to President Lincoln late that night, thus further dispelling the myth that the “12 M” on the document stood for noon and not midnight.

It seems clear the move to discredit McClellan’s response was politically motivated. Explain.

AR – Yes, the evidence shows this was the case. In late 1863 and into 1864, assaults on McClellan’s military record began appearing in Republican-leaning newspapers and pamphlets distributed by Radical Republican organizations. The attacks levied by William Swinton in particular “exposed” McClellan’s questionable (in Swinton’s opinion) record as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Most of this criticism focused on the conduct of the campaign on the James River peninsula outside Richmond, but it eventually also spilled over into a critique of McClellan’s command in Maryland. It certainly helped Swinton that Henry Halleck had uttered his “six-miles-per-day, slow marching” slander during the Harpers Ferry Military Commission hearings. In addition, that Commission unreasonably censured McClellan for not rescuing Colonel Dixon Miles’ garrison in time even though it ultimately laid blame for the surrender on Miles himself. This all became fodder for the partisan press, and they made the most of it.

An ugly personal element to all this also emerged. Swinton declared openly, unlike most of the disingenuous reporting we see today, that he specifically intended to dissect and expose McClellan’s character flaws to show why he should never be president. This is where the tendency originated to render personal judgments against Little Mac. Unfortunately, they have since come to color every aspect of McClellan’s command, whether it was in Virginia or Maryland.

Would this issue have ever attained the status it still has had McClellan not run for president in 1864?

GT – Perhaps not to such an extent. Great mistakes were made early in the war and the Lincoln administration wanted to draw attention away from them. These blunders included closing all the recruiting stations in April of 1862, just as the Union armies were beginning their first major advance across all fronts, and at the same time removing McClellan from the position of senior commander of all armies and not replacing him with anyone. This effectively left two lawyers with no real military experience—Stanton and Lincoln—responsible for all strategic operations until Halleck was appointed as general-in-chief three months later in July. By then, the damage had been done. An almost-unbroken six-month string of victories by the Union forces under McClellan during the fall and winter of 1861-62 was turned into an almost continuous series of defeats under Stanton, Lincoln, and Halleck until the Confederate advance was ultimately stopped after McClellan was returned to command in September 1862. Supporters of the Lincoln administration could not allow it to be seen as the source for these disasters, so blame for the reversals was directed at McClellan, even though the coordination of his movements and troop levels was tightly controlled by the administration.

Those blunders and how McClellan overcame them can be found in two op-ed pieces I wrote titled In defense of McClellan: A contrarian view, and In defense of McClellan at Antietam: A contrarian view for The Washington Post on March 2 and September 7, 2012, respectively.

AR – I doubt it. We point out, in fact, that from October 1862, when the Harpers Ferry Military Commission was meeting, until late 1863–early 1864, after McClellan had announced his presidential candidacy, nothing had been made of the Lost Orders. Knowledge of them was around, too. For example, newspapers had reported the orders’ discovery during the campaign itself. It is really only after McClellan declares his candidacy that criticism of his wartime record becomes the centerpiece of the Republican strategy to destroy McClellan’s reputation. That’s politics. We get it. Politics still cannot be allowed to stand in for history, insofar as the evidence provides insight into the truth. The fact of the matter is that most of the elements of the wartime smear campaign against candidate McClellan remain key components of his postwar reputation. That is not fair to the man whatever you may think of him.

Why were the defenses of McClellan after the war by Lee himself and later the Comte d’Paris so readily downplayed or ignored?

GT – I’ll let McClellan answer this question in his own words when he wrote in 1881, four years before his death, “…party feeling has run so high that the pathway for the truth has been well-nigh closed, and too many have preferred to accept blindly whatever was most agreeable to their prejudices, rather than to examine facts.”

AR – I tend to think that by those early postwar years—say, for the first decade after the war—very few people wanted to dwell on what had just occurred. A cataclysmic event, the war had ended with half of the nation in ruins, or at least economically devastated, and hundreds of thousands killed and wounded. A president also had been assassinated, which was a first in American history at that time. People simply wanted to focus on the future and westward expansion. It would take a few decades for veterans and others to start writing about the war in earnest. By that time, details such as those offered by Lee and the Comte d’Paris meant little. This is particularly the case because the war ended chattel slavery. McClellan and many of those around him had never wanted to abolish slavery, so what they represented probably seemed out of touch with the course of events. It proved easier to just forget the past and move on.

I’m not sure how you felt about Halleck before doing this study, but how much has your opinion changed?

GT – When I began the study, almost 25 years ago, I didn’t have much of an opinion about Halleck at all. I guess that’s because I didn’t fully realize how much control he had over operations during the Second Manassas and Antietam campaigns as McClellan’s boss.

My opinion of Halleck now is not very high. I’d argue that it was he who was the overcautious general and not McClellan. I also find Halleck worthy of censure because that instead of taking responsibility for his own failures, he unfairly shifted the blame for them to McClellan.

AR – I’ve never had a high opinion of “Old Brains,” and after doing this study my opinion of him is even lower. To think that Lincoln relied so heavily on someone like Halleck to make important strategic decisions is mind-boggling. The man was jumpier than a cat on hot bricks. It helps explain why Federal efforts in the first year of the war in the East failed so badly. I also learned recently that Halleck was a habitual user of opium at the time. This could explain some of his poor decision making, but I am not entirely certain on that score. Either way, Halleck should have been left to army-level command, as he himself wanted, and never been brought east to serve as general-in-chief.

Did you learn anything particularly shocking from this study?

GT – To prepare for this book, I’ve read every telegram, letter, diary, regimental history, newspaper, relevant sections of the Official Records, and other primary source I could find related to the Antietam Campaign to learn from those who were there exactly what they experienced. I’ve been shocked by how much of what they recorded has been left out of mainstream history books. But that’s something I think both Alex and I hope to change with The Tale Untwisted, and hopefully many more titles in the future.

AR – I agree with Gene about the shocking level of missing primary source material. Here is just one example. For more than 100 years we have been told, based on an error made by Jacob Cox, that McClellan sent his “Trophies” telegram to Lincoln at noon or “12 M” on September 13. Gene presents a slide during our live talks that contains 10 sources that show the 12th Corps did not arrive at its position outside of Frederick until around noon. Consequently, there is no way that McClellan could have written and sent his telegram at noon. The Lost Orders had not even been found until that time, much less sent to army headquarters. The sources Gene shows are all easily obtainable, especially now in the age of scanned documents on the Internet.

Even 20 years ago, these sources—being unit histories and letters—would have been readily available at most research libraries. Why weren’t they used? They prove beyond a doubt that even without the “12 Midnight” copy of the “Trophies” telegram discovered by Maurice D’Aoust sufficient evidence existed to dispute the noontime accusation argued by Stephen Sears and others. Nevertheless, they ignored that evidence. The proper question to ask in this context is why.

Interview conducted by America’s Civil War Editor Christopher K. Howland.