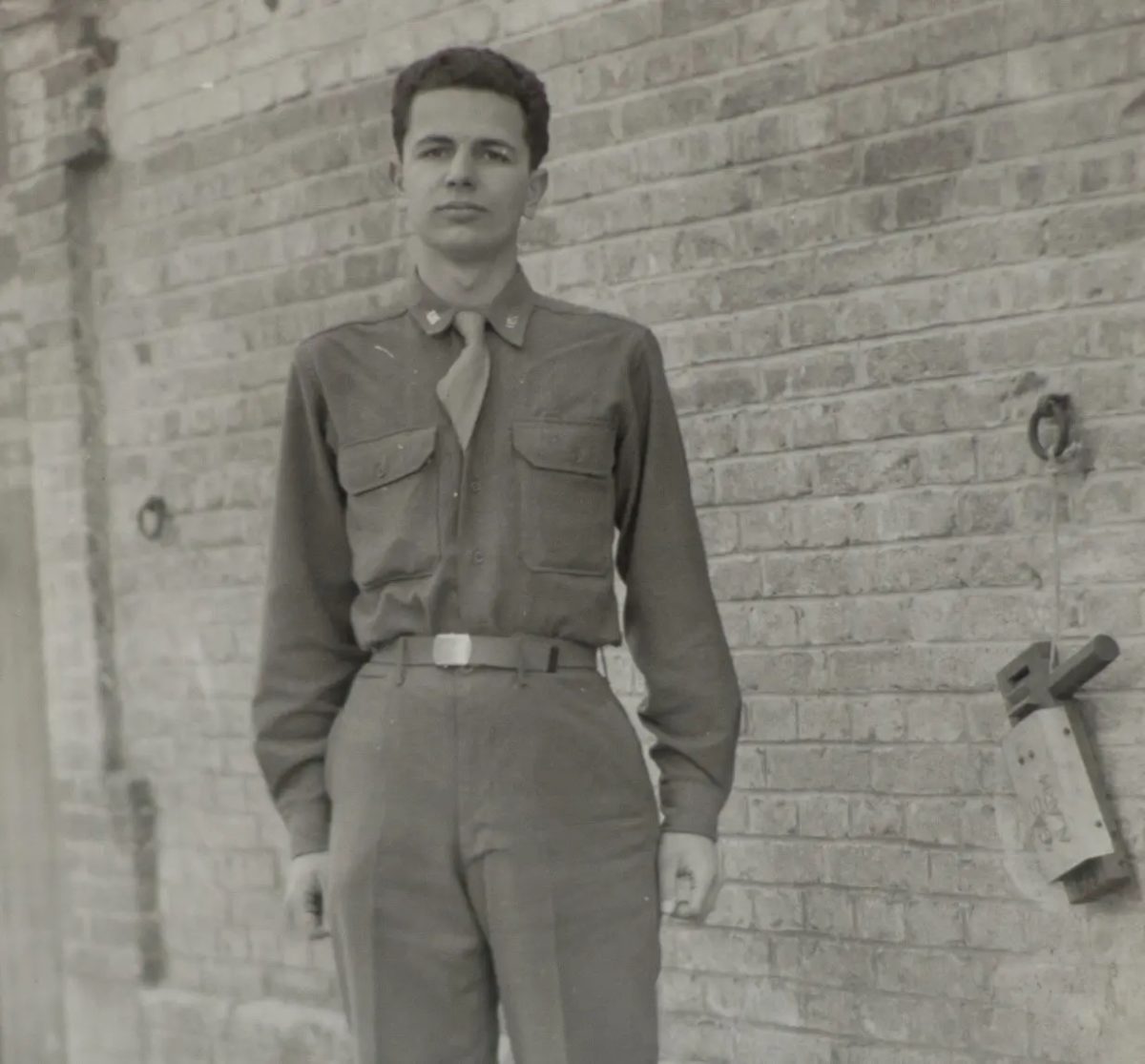

Maximilian Lerner, one of the last surviving members of the “Ritchie Boys” — a World War II unit that was deployed as skilled linguists and interrogators to fight the Nazis — has died. He was 98.

Early in the war, the U.S. Army recognized its need for skilled linguists to interrogate captured enemy troops or conduct covert operations in Axis-controlled areas. Recruits included both Americans who could speak German, Italian and Japanese and immigrants who had fled Europe and Asia for the United States. Among them were the “Ritchie Boys,” some 15,200 men who attended the Military Intelligence Training Center at Camp Ritchie, in Cascade, Maryland.

Among those men was Lerner, an Austrian-born Jew who had immigrated to the United States with his family in 1941.

Last year, when asked during a “60 Minutes” interview what he was trained to do during the wear, Lerner’s response was clipped:

“Wear civilian clothes, pass messages, kill,” he said.

As America entered the war, the 18-year-old Lerner enlisted in the Army, doing his basic training at Fort Pickett, in Blackstone, Virginia. However, after three weeks and an I.Q. test, Lerner was sent to Camp Ritchie, where his language skills in French and German and knowledge of recent events in Europe were seen as a boon for the Allies.

According to The New York Times, Lerner’s “European military service began in 1944 in Northern Ireland, where he was recruited by the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor of the C.I.A., and trained with the British in strategic wartime intelligence techniques. For more than a year, he served with the O.S.S. and the Army Counter Intelligence Corps in a variety of ways.”

When Paris was liberated in August of 1944, Lerner briefly served on the staff of Gen. Jacques-Philippe Leclerc, who commanded the French division that helped to liberate the city. Lerner was tasked with weeding suspected collaborators; German soldiers masquerading as French civilians; officials of France’s pro-Nazi Vichy government; and ordinary citizens who had gotten swept up in the fray.

Among those rounded up and brought to Lerner for interrogation was an SS major.

“When I saw him standing before me, a tremendous wave of hatred swept over me,” Lerner wrote in his 2013 memoir “Flight and Return: A Memoir of World War II.”

“He represented all the evil that he and his kind had brought into the world.”

Resisting the impulse to attack the prisoner, Lerner wrote, he began his interrogation “with complete courtesy.”

Following the German surrender, Lerner was sent to Wiesbaden, Germany, to help with denazification. Among the men he interviewed was Julius Streicher, the founder and editor of the antisemitic Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer.

Streicher was later tried and convicted of crimes against humanity during the Nuremberg war crimes trials and hanged in 1946.

“I made sure that he and others I arrested knew that I was a Jew,” Lerner wrote.

As for the impact of Lerner and the Ritchie Boys? This small unit had an outsized impact on the war. David Frey, a professor of history and director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the United States Military Academy at West Point, told the Times that the Ritchie Boys produced “least 60 percent of the actionable intelligence in the European theater and [made] substantial contributions in the Pacific theater as well.”

“This was our war,” Guy Stern, a fellow Ritchie Boy, told HistoryNet in 2020. “Many of us were Jewish refugees, so we worked harder than anyone could have driven us.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.