Tohono O’odham Indians spearheaded an attack against sleeping Apaches in 1871, but Mexican and white residents of Tucson were behind the notorious Camp Grant Massacre.

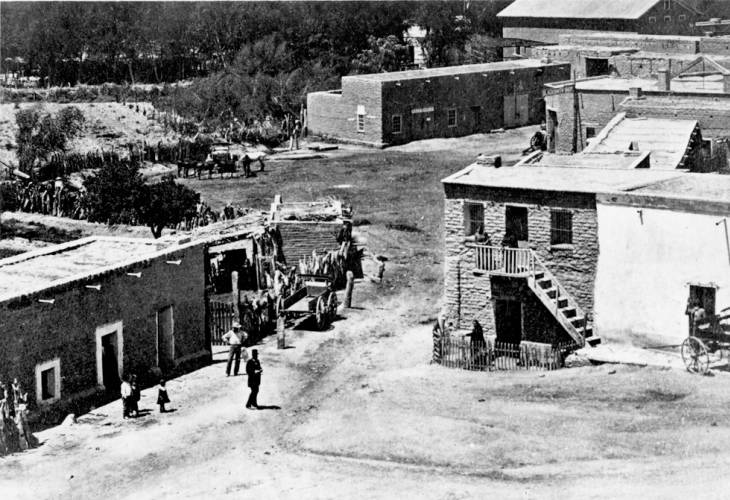

By 1871 citizens in Tucson, then capital of Arizona Territory, had such utter disregard for all Apaches—men, women and children—that the phrase “nits make lice” was as commonplace around town as saguaro cacti were in the surrounding desert. Tucsonans regarded the killings of Indians, regardless of the reason, as laudable, but when Indians, justified or not, killed white settlers, that was an unpardonable offense that could not go unpunished. The local Arizona Citizen fostered the notion that Indians were outlaw raiders who should be eliminated, and the people felt justified in their outrage, as Apaches had staged stock raids and committed murders, including a recent strike on nearby Mission San Xavier del Bac.

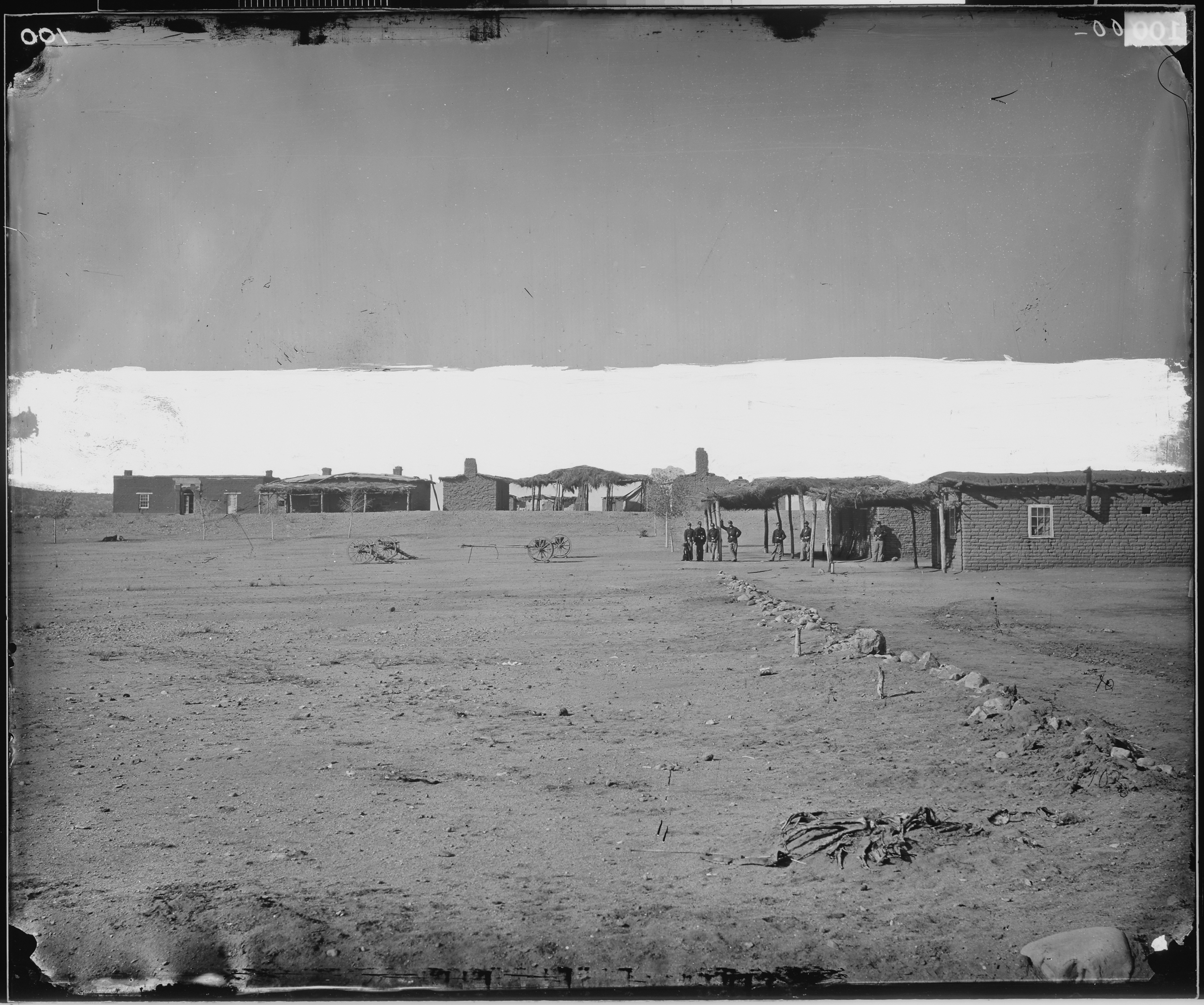

At Camp Grant, about 60 miles north of Tucson, though, commanding officer Lieutenant Royal Emerson Whitman fervently denied that his Apaches had committed any recent depredations, citing a system of counting that would have recorded the departures of any Apaches from the region. Oral narratives of the Aravaipa and Pinal Apaches living near Camp Grant likewise reflect their bewilderment at the accusations against them in a time of peace.

Nevertheless, a civic group of prominent Tucsonans known as the Tucson Committee of Public Safety, with prompting from disgruntled citizens, decided to do something about the “Apache problem.” Together, the whites, led by influential William Sanders Oury, and the Mexicans, led by Jesús María Elías, came up with a plan of attack. Their target was most visible, very accessible and rather vulnerable—namely the Apaches at Camp Grant. The committee recruited Tohono O’odham headman Francisco Galerita at San Xavier to convince his people, who had long considered the Apaches their enemy, to do most of the dirty work. On April 28, 1871, 92 O’odhams, at least 42 Mexicans and six whites (including Oury) set out on their secretive mission. In the pre-dawn hours on Sunday, April 30, they surrounded the camp of Aravaipa and Pinal Apaches. The slaughter that ensued has come to be known as the Camp Grant Massacre, and unlike many other so-called massacres in the West, this one is hard to call by any less inflammatory name.

Today, State Route 77 runs south from the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation toward Tucson through the lower Sonoran life zone dominated by saguaros, the road climbing some 2,000 feet within the first 10 miles. Skirting the eastern side of the Pinal Mountains, in the shadow of the jagged cliffs of El Capitan, the road soon attains the saddle separating the Pinal from the Mescal Mountains to the east. Here in the upper Sonoran, big cacti have given way to piñon pine, manzanita and yucca. Farther up the mountain the stately ponderosa pine replaces the scrubby piñon. To the north is the panorama of Cassadore Knob and other landmarks on the San Carlos Reservation (which was established in 1872). The southern expanse presents equally spectacular views of the Galiuro Mountains and, on clear days, the Santa Catalinas on Tucson’s northern outskirts. Then the highway plunges with a vengeance into the lower Sonoran zone while temperatures soar and towering saguaros, ocotillos and century plants return to riddle the sprawling valley of Dripping Springs Wash. Wending ever downward, the road drops through the lush canyon bottom of the Gila River to the mouth of the San Pedro.

Signs of human habitation are sparse—scattered ranches and villages—as the highway approaches easily missed Aravaipa Road. Where present-day Central Arizona College stands, Fort Breckenridge briefly stood at the outset of the Civil War, defending the settlers of Tucson, Sonoita Creek and the Santa Cruz River Valley from Apaches. After the war on this same ground Camp Grant sought to protect the settlers from the Apaches, and vice versa, but with less success. Most travelers pass this intersection without a glance, unaware of the dramatic and tragic events of more than 142 years ago deeply impacting all involved. There is no marker, no apparent ruin, nothing significant to relate the events or repercussions that linger to this day.

The surrounding mountains and valleys were the geographic anchors for the Aravaipas (Tséjìné, or “Dark Rocks People”) and Pinals (’Tìs’évàn, or “Cottonwoods in Gray Wedge Shape”), Western Apaches today numbered among the four bands associated with the San Carlos Reservation (the other two being the San Carlos proper and Apache Peaks). The Aravaipas’ traditional homeland was Aravaipa Creek and the lower San Pedro Valley, while the Pinals dwelt in the Pinal Mountains to the north. Apaches know this region as Arapa. Both Aravaipas and Pinals lost relatives in the Camp Grant Massacre.

At the time of the massacre the Aravaipas were under the leadership of Eskiminzin, or Haské Bahnzin (“Angry Men Stand in Line for Him”), a Pinal who had married into the band. Described as strong, well postured and intelligent, he commanded respect and was savvy in the ways of both his people and the Americans. Still, he occasionally made bad decisions, which combined with bad luck, bad Apaches and bad whites to undermine his work toward peace and assimilation. The assault near Camp Grant on the last day of April 1871 would be enough to demoralize and destroy any leader, but he was a resilient, adaptive survivor who continued to reinvent his life as well as the lives of those around him.

The actual assault was quick and lethal. Once the Tucson force had completed its stealthy early-morning approach on the 30th, it attacked the sleeping Apache village with a vengeance. The attackers used guns, but also knives and clubs. Most of the victims were women and children, as almost all the Aravaipa and Pinal men were off hunting in preparation for an upcoming celebration Lieutenant Whitman had encouraged. Exactly how many Apaches died in the massacre is not known, perhaps as few as 85 or as many as 144. It is known that only eight of the corpses were men, the rest women and children. Nearly 30 Apache children were captured, most forever lost to surviving relatives. Some entered the households of their captors, while the rest were sold into Mexican slavery in Sonora.

Distrust, betrayal and disdain had festered for some time among the people of the territory, and now those endemic emotions ran rampant. The Americans ignored the reality of the poverty and starvation forced on a proud people by overhunting and occupation of prime lands. The success of unscrupulous traders relied on the continued presence of both the Army and the dependent Indians to whom they could sell, through Indian agents, flour, hay and cattle. Indians who did successfully feed themselves or who sold hay directly to the cavalry were thorns in the sides of influential merchants. Stories of Apache depredations filled the papers, as did pleas for more soldiers to patrol the territory. The perception that white and Mexican Americans were at the mercy of unprincipled Apaches is somewhat misleading, however. Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh studied territorial newspapers and reports in his book Massacre at Camp Grant that between 1866 and 1878 in southern Arizona a total of 1,759 Apaches were killed compared to 493 non-Apaches. Apache raids and depredations, as well as attempts by the Army and settlers to retaliate, would continue to some degree until the Apache wars ended in 1886, with the surrender of Geronimo, and even into the 1920s there were several smaller, less-publicized hostilities.

Events leading to the Camp Grant Massacre have their roots in preceding centuries when the Spanish at Mission San Xavier encouraged their allies the O’odhams to protect their colony from raiding Apache bands. Western Apaches hunted, gathered, traded and raided well into Sonora, Mexico, and as far as the Gulf of California. They raided the O’odhams, the Spanish, the Mexicans and, ultimately, the Americans, who made their presence felt after the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican War and after the 1854 Gadsden Purchase from Mexico further expanded the American domain.

The Apaches regained some control over their territory during the Civil War, but not entirely. In fact, in a prelude to the better known and bloodier Camp Grant Massacre, in May 1863 Captain Thomas T. Tidball led a force of California volunteers, Mexican and American civilians and their Indian allies on an attack of Apaches in Aravaipa Canyon, killing 50 and wounding and capturing dozens more. The stakes kept getting higher for the Apaches, who had moved beyond raiding to more serious depredations as they fought for their way of life and livelihood. But by 1871 many Apaches liked the idea of peace better. That February five older women from Eskiminzin’s band, destitute in appearance, arrived at Camp Grant, and Lieutenant Whitman treated them with kindness and courtesy. Such conduct reassured Eskiminzin, his father-in-law, Santo, and Pinal chieftain Capitán Chiquito. Eskiminzin expressed desire for a peaceful, stable existence for his people on their ancestral homeland along Aravaipa Creek. Whitman lacked the authority to establish a treaty with the Apaches, but he made an arrangement in which the Apaches would provide hay for the military in exchange for needed supplies, and he encouraged local ranchers to hire these Apaches as workers. Peace and stability actually seemed possible with the growing trust between this visionary lieutenant and the dynamic Eskiminzin.

In Tucson, though, most citizens ignored or dismissed reports of the good relationship forming between the Army and Apaches in the Aravaipa region. The conviction to eliminate the “hostiles” was too deeply ingrained. Vigilante justice gained momentum there during the winter of 1870–71. Tucsonans did not trust Apaches, nor did they trust the Army to protect their lives and property, especially after Captain Frank Stanwood visited Camp Grant, expressed satisfaction with the Apaches’ conduct and endorsed the truce. With citizens up in arms, the Tucson Committee of Public Safety devised its preemptive strike. Whites and Mexicans alike were ideologically committed to the plan of violence against the Camp Grant Apaches, but they proved reluctant to commit to the action. Though some 80 whites promised assistance, only a half-dozen of them marched with the force to Camp Grant. Nearly twice as many Tohono O’odhams as Mexicans participated, and the Indians were the primary fighters on April 30.

It is easy to be misled by the small number of whites involved in the actual massacre, but without their planning and influence, the attack never would have occurred. For instance, Arizona Territory Adjutant General Samuel Hughes, a prominent Tucson merchant and politician, did not go to Camp Grant but vigorously approved and supported the well-conceived attack plan. To prevent word of the impending strike from reaching Lieutenant Whitman, the planners arranged to block the Cañada del Oro military road to Camp Grant, while the main body took a concealed trail over the mountains by way of Redington Pass to the east (see map at right). The Apaches were more vulnerable than usual at the time, as they had recently moved, with Whitman’s permission, well upstream from Camp Grant to Gashdla’á Cho O’aa (Big Sycamore Stands Alone), preferring its free-flowing spring water to the sand-choked streambed near the fort. When the shooting and screaming broke out just before dawn on the 30th, the soldiers at Camp Grant were too far away to hear. And when some of the terrified Apaches ran for their lives, the whites and Mexicans in reserve were in position to pick them off. In short, historical accounts that emphasize the large number of Tohono O’odhams involved in the massacre obscure and distort the central roles of the whites and Mexicans.

All the killings took place within a half-hour, and the casualties were all on one side. Not a single white, Mexican or Tohono O’odham was so much as wounded. When Whitman finally did get word of what was happening, he dispatched soldiers upstream, but they arrived too late to help the Apaches. All the soldiers could do was bury the dead and try to reassure survivors hiding in the mountains. Eskiminzin had been one of the few Apache men in camp. He had barely escaped after fleeing from his wickiup with his infant daughter in his arms. His wives and other children died.

Whitman and many of his soldiers were no doubt horrified by what they saw at the massacre site. But in Tucson the reaction was completely different, with newspapers, citizens and government leaders celebrating the victory over the enemy and honoring as heroes the leaders of the surprise attack.

Back East the response was quite different, with President Ulysses S. Grant calling the Camp Grant attack “purely murder.” District Attorney Converse W.C. Rowell was directed to obtain indictments against the perpetrators but met with stiff local resistance and was even burned in effigy. Grand jury secretary Andrew Cargill snuck a peek at a telegram from U.S. Attorney General Amos Akerman instructing Rowell to get an indictment in three days, or he would declare martial law, which would mean a military court with Army officers serving as a court-martial board in lieu of a jury. As a result of the threat the grand jury quickly named Sidney R. DeLong the lead defendant among 100 (many identified only as Indians of San Xavier del Bac) on an indictment for the murder of 108 Apaches. The defense focused on Apache depredations in an attempt to justify what happened near Camp Grant—not a massacre, they insisted, but self-defense. After deliberating just 19 minutes, the Tucson jury, as might be expected, found all defendants not guilty. At the time the perpetrators expressed little remorse for what they had done. Much later DeLong stated that his only regret in life was having taken part in the Camp Grant affair.

Today the area around the unmarked and relatively unknown Camp Grant Massacre site is largely home to non-Apaches, though the Bureau of Indian Affairs holds 160 acres in trust for the 100-odd Apache descendants of the massacre victims. This group is sharply divided over disposition of the site. One concern is that if its location is disclosed, the site would be left vulnerable to exploitation and desecration. Under consideration since 1996 is a plan to erect a descriptive historical roadside marker on State Route 77 that would inform the public about the infamous event without jeopardizing the anonymity of the site. Those who seek something more lasting, namely a historical and cultural interpretive center at the site, suggest a sensitive telling of the tragedy would not only educate the public about the horrific event but also promote discussion about broader issues of human aggression.

Memorializing the site could cause greater pain for descendants of the victims. On the other hand, it might aid in the healing process. On April 30, 1984, near the Camp Grant ruins, Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts and Representive Morris K. “Mo” Udall of Arizona joined many Apaches, including Apache spiritual leader Philip Cassadore, for a memorial event on what Governor Bruce Babbitt had declared Apache Memorial Day. In October 1996, a group of 80 Tucsonans came to the San Carlos Reservation to apologize to the Apache people for the Camp Grant Massacre. San Carlos and White Mountain Apache elders and leaders were among the Indians on hand for this day of forgiveness and reconciliation. The group established a fund for a permanent marker in the region to remember the massacre.

Two years later, thanks to the efforts of people like Dale Miles, a San Carlos Apache who was tribal historian from 1993 to 1998, the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. John Hartman, director of the executive board of Apaches of Aravaipa Canyon, praised the move to protect the site. Printers release new Camp Grant Massacre studies nearly every year, evoking profound emotions among Western Apaches. As Western Apache scholar Keith H. Basso noted in his book Wisdom Sits in Places, Apaches form an intricate connection between place and identity. Despite all the loss and sorrow in the Arapa region, the Western Apaches’ connection to it will last and even lift spirits at least as long as the saguaros stand.

Carol A. Markstrom is a professor at West Virginia University, but she has a home in Tucson and is working to help preserve the Camp Grant Massacre site. Doug Hocking, raised on the Jicarilla Apache Reservation and now living in Sierra Vista, Ariz., researches and writes about Apache history. Suggested for further reading: Massacre at Camp Grant: Forgetting and Remembering Apache History, by Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh; Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History, by Karl Jacoby; The Camp Grant Massacre, by Elliott Arnold; and Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apaches, by Keith H. Basso.

Originally published in the October 2013 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.