Exclusive interview with inventor who changed the world

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]ARTIN COOPER, SEMI-RENOWNED since 2009, when The Economist featured him in an article the magazine headlined “Father of the cellphone,” is part engineer, part salesman. In his 29 years at Motorola, Cooper helped that company pioneer two-way radios, pagers, and crystals in wrist watches. In 1973, he led the team that made the first portable phone. But Cooper, now 89 and running his own companies with his wife, also excels at pitching. As cellphone history attests, he understands the value of what he refers to as “dazzle,” and what he’s ultimately selling reaches far beyond product.

Marty Cooper is selling visions of the future.

Cooper is quick to acknowledge the many contributors to cellular technology’s development. That arc began with two-way radios and morphed into the car phone, an AT&T coup. But Cooper had a different concept, of people walking around using a phone wherever they went, untethered to a vehicle, its

battery, or that bulky trunk-mounted radio. That vision triggered what amounted to a war over electronic real estate between AT&T and Motorola, speeding Cooper’s concept to fruition.

A Chicagoan who served in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War, Cooper has a master’s degree in electrical engineering from the Illinois Institute of Technology. After a stint at Teletype Corporation, an arm of AT&T—Cooper’s future nemesis—he joined Motorola in 1954.

In the early 1970s, AT&T and its Bell Telephone Laboratories lobbied the Federal Communications Commission, which regulates the airwaves, to grant the company exclusive license to radio spectrum the corporation would need if it wanted phones in millions of cars and perhaps, in the distant future, in hands. Cooper, a Motorola division head, saw the truly portable phone as a way for his company to play David to AT&T’s Goliath. If his team could build a portable device and show that it worked, he believed, the smaller company could convince the FCC not to give AT&T a monopoly. “We have to do something spectacular,” he wrote in a company memo.

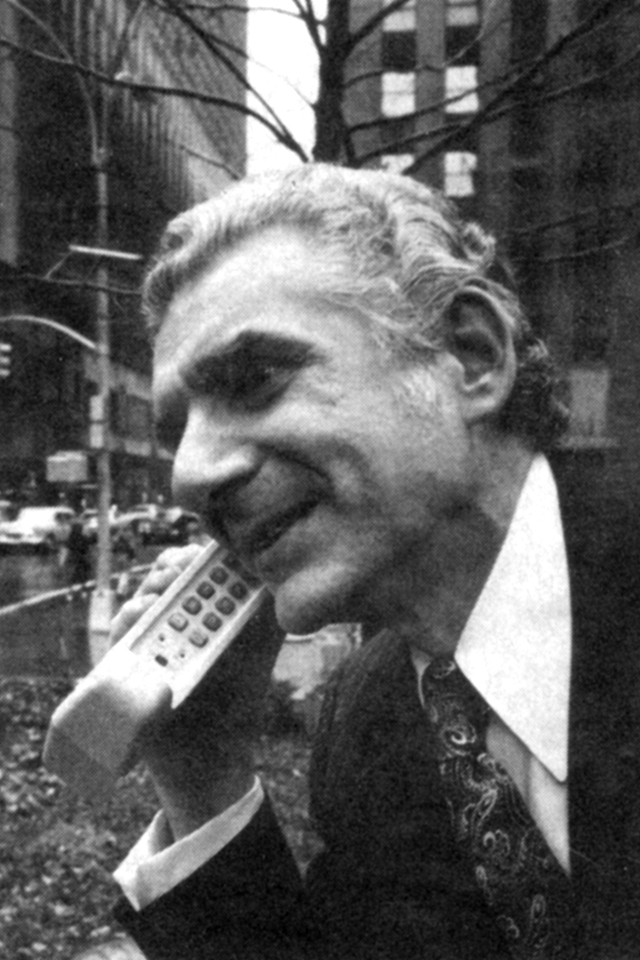

Three months later, Cooper’s team had a prototype, essentially a miniaturized mash-up of existing two-radio technologies. Seeking a media splash, Motorola flamboyantly demonstrated the unit. Lead pitchman? Marty Cooper, who made the first public call with the phone—an ungainly brick of a thing—from the streets of New York City.

Who did Cooper call? His main rival at AT&T.

A decade passed before Motorola actually sold a mass-produced cellphone, but that first call resonated at the FCC, and today, platoons of carriers share the country’s airwaves.

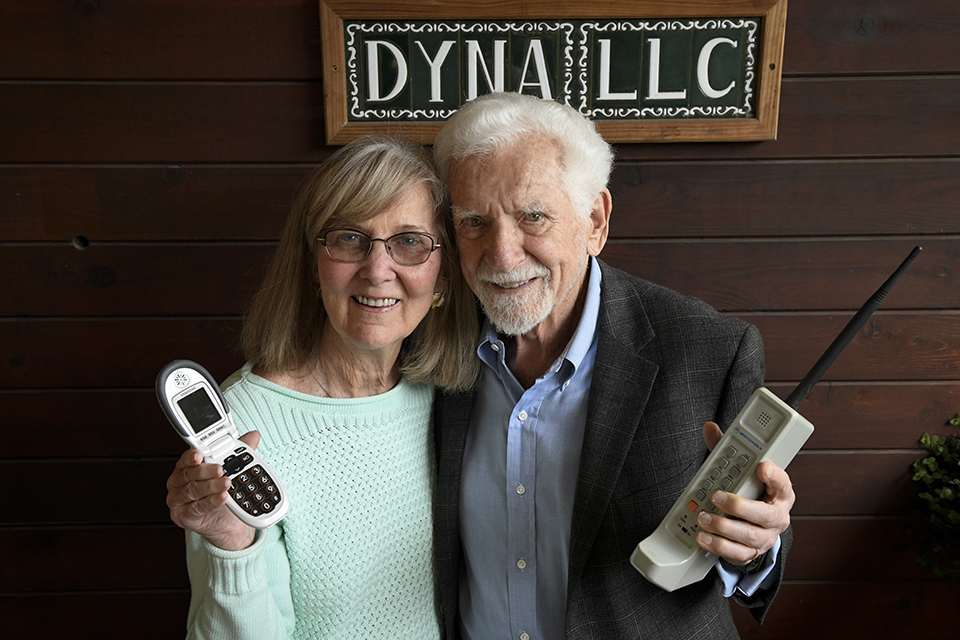

Cooper left Motorola the year the cellphone reached market and soon had started his own outfit, Dyna LLC. Based in Solana Beach, California, a seaside town in northern San Diego County, Dyna bills itself as “insightful, innovative, relevant.” In the past decade, Cooper has received several honors, including the Marconi Prize, which recognizes exceptional contributions to communications, the Charles Stark Draper Prize from the U.S. National Academy of Engineering, and top billing in a 60 Minutes segment, “Marty Cooper’s Big Idea.”

Cooper and his wife Arlene Harris, Dyna’s co-founder, live near the company office in a beachfront house in adjoining Del Mar. Harris, whose family worked in telecommunications, started a second company with Cooper, GreatCall, which creates technology for seniors. One product is the Jitterbug, a no-frills cellphone with oversized buttons. “I’m 20 years younger than Marty and I have trouble keeping up with him,” she says.

Cooper met with American History in the Dyna conference room amid displays of early cellphones and reprints of articles celebrating the co-founder’s centrality to an invention that nearly five billion people now use. Cooper is physically fit, mentally sharp, and relentlessly curious. A kind and earnest Midwesterner, he also can be cantankerous and feisty—but never short on opinions, especially about tomorrow.

Jon Cohen: How old are you?

Martin Cooper: I’m 89.

JC: Growing up on the west side of Chicago in the 1930s, did your family have a phone at home?

MC: My first recollection of a phone was a party line. But very soon we had one phone, a rotary dial telephone on the wall. The number was RO 8646—ROckwell 8646.

JC: You still remember it!

MC: Yes, but don’t ask me what I had for dinner last night.

JC: Your parents were immigrants. Where were they from?

MC: Russia—now Ukraine.

JC: Did they live to see your invention?

MC: My mother did; my father did not.

JC: Do you remember what she thought of it?

MC: The cellphone had no meaning to her whatsoever. She would have preferred me to be a doctor. But she was proud of me regardless and I credit her

for all my useful attributes.

JC: You served in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War. How were you in the military?

MC: Oh, I understood orders and I followed them as best I could. I tried to do what the underlying requirement was. What was the objective? Even in the military you don’t follow orders blindly.

JC: Was that when you got into radio?

MC: I didn’t get into radio until I went to work at Motorola in 1954.

JC: Was that straight out of the service?

MC: No, after the Navy I went to work at Teletype. Teletype was a division of Western Electric, part of the Bell system, that made mechanical typewriters for transmitting information. People remember those machines and their clickety-clack. I sat in a huge room with hundreds of other engineers. It was the kind of place where at 5 o’clock a bell rang, and everybody stood up and walked out—like a big machine. That was when I started having an adversarial relationship with the arrogant monopoly culture at Bell and AT&T. I got on well with individual Bell Labs researchers, but monopolies are bad.

JC: How did you make your escape?

MC: Motorola recruited me. My future bosses made me solve problems like the minimum bit rate for digitizing a sine wave. I had to work it out in front of them on a chalkboard.

JC: Was Motorola like AT&T culturally?

MC: Motorola was very different. If someone thought of a technical issue at a quarter to 5, we’d start a discussion and not go home `til we finished—totally unlike Bell.

JC: Walk me through the invention of the cellphone.

MC: From when I conceived of a portable phone and when we demonstrated that portable phone was a little over three months. But the technology in the device had been part of my dream for years. The understanding that personal communications was going to be really important was something my mentor at Motorola, John Mitchell, infused into me. We got it from the marketplace for two-way radios.

JC: How did Motorola get into the two-way radio business?

MC: Motorola built most of the walkie-talkies used during World War II. The walkie-talkie led to the first commercial pager and the handheld two-way radio. Motorola built virtually all the police, fire, and business communications systems like those your plumber and electrician use. Competing with RCA, GE, and others, Motorola led the world in two-way radios, and when the technology became available we moved into handheld devices. My team, led by chief engineer Richard Carsello, introduced the world’s first citywide pager as well as the system for

paging nationwide.

JC: What’s an example of the portable device marketplace at work?

MC: In the early 1960s, I was running the portable products division. Chicago Police Superintendent Orlando Wilson asked us to help officers communicate on the street and in their cars. We built a radio that we called “the brick,” from its shape. A cop wore the brick on his hip and a microphone with an antenna on his shoulder. When the officer was in the car, the radio antenna was at window height, able to pick up signals, and he also could communicate well outside the car. But those radios were not able to transmit far, so the officers using them had to be near one of many base stations. A typical police radio conversation was about 12 seconds, so they never were out of range as they moved through the city.

JC: Wasn’t the original mobile phone the car phone?

MC: In 1947, a Bell engineer named Doug Ring and his boss, Rae Young, wrote a memo describing cellular technology. AT&T decided the time wasn’t right for cellular, but in the `50s Bell introduced a pushbutton analog phone system for cars. The system was like a party line—when someone wanted to reach you, an operator would dial. Everyone was on the same channel, so they could listen in on your call. But big shots had to have these gadgets. My wife worked for a common carrier providing that service. She was 12, at a switchboard, hooking Jerry Lewis up to his girlfriend. That was mobile telephony. The service was awful.

JC: Did you have one?

MC: No. We at Motorola didn’t know what it was until Bell decided to build a nationwide dial car phone system. We were building the phones for that system. Bell would buy our two-way radios and put in this ringer gadget. Instead of a cellular system, AT&T decided to build the improved mobile telephone system and to delay cellular indefinitely. An entrepreneur named Chan Rapinsky invented a device that converted a two-way radio into an automatic car phone. AT&T adopted that system. Motorola wanted in on that business.

JC: For that business to happen, AT&T needed bandwidth.

MC: Yes. AT&T requested frequencies from the Federal Communications Commission. The FCC allocated AT&T maybe 50 UHF 150-megahertz radio channels.

JC: Are base station radio and cellular identical?

MC: Radio is radio—receiver, transmitter, base station. A cell is a base station connected to other base stations and to the public switched network. When a user moves from one cell to another the call transfers seamlessly from one radio channel to another; we call that “hand-off.” That’s the difference between a cellphone system and what we did for Superintendent

Wilson in Chicago.

JC: What technological leap let you connect different cellular regions?

MC: My understanding is that Rae Young came up with this hand-off concept. The actual switching logic was by a guy named Amos Joel at Bell Labs. I had an interchange with Amos Joel’s children who got angry because someone called me the father of the cellphone and they thought he was. I met them and we became friends.

JC: You’re not the only father?

MC: I’m not minimizing what I did. But the invention itself is not important. What’s important is having an idea that contributes to society. If it’s a good idea, it will have a life of its own and become reality. The vision, the invention, and the execution are all important.

JC: What was your essential contribution?

MC: It was my idea, and, I guess, my invention. I was lucky enough to have brilliant engineers and designers who taught me the basics.

JC: When did this start to heat up?

MC: In 1969, AT&T said they were ready to introduce cellular technology. But AT&T didn’t see much of a market—about two million car phones, an elite service only a few people would want. They told the FCC, “We want 30 megahertz of radio channels and we want a monopoly.” They wanted that monopoly to include car phone service and two-way radio—and air-to-ground radio, which didn’t exist but which competitors were proposing.

JC: How did that sit with Motorola?

MC: Motorola didn’t believe in monopolies, even though we virtually had earned one in two-way radio. Motorola was a billion-dollar business, AT&T was a $22 billion business. AT&T was going to take our business. And there was a technical reason to oppose Bell. If you mix different traffic in the same system you end up having to deal with all kinds of inefficiencies.

JC: How about a primer on radio spectrum?

Radio waves exist in bands, like colors. AM radio appears in the band 535 to 1600 kilohertz (kHz). FM radio is in 88 to 108 megahertz (MHz). A station

broadcasts within a sliver of frequencies called a “channel” in a given band. An AM station takes up 10 kHz. An FM station takes up 200 kHz, so FM stations have higher quality. Two-way radios, like the police, firefighters, and businesses use, broadcast in bands around 25 to 50 MHz, 152 to 174 MHz, and 452 to 470 MHz. In those bands, channels span 25 kilohertz. Cellular telephony began, in 1983, in a band around 900 MHz. If the FCC had assigned AT&T 30 megahertz of radio channels, they could have accommodated 600 voice channels. Before cellular technology, the most the government ever allocated was a dozen or so radio channels.

With new technology, bands as high as 2700 MHz are used in cellphones. All cellphones today are digital—they send your voice as a binary digital signal with a bit rate of about 12.5 kilobytes per second.

JC: What did Motorola do?

MC: We took AT&T on for years. Motorola had three people in Washington, DC, lobbying the FCC; AT&T had 200. We appeared at hearings and filed reams of testimony. I was practically living in Washington.

JC: How was it that 900-megahertz spectrum

got involved?

MC: AT&T wanted 30 megahertz of channels for their exclusive use. Motorola believed AT&T could get by with much less. Motorola needed more channels for their growing two-way radio business. The solution I worked out with the FCC was to set aside 20 MHz for AT&T and one or more competitors and 20 MHz of channels for Motorola and others for two-way radio service. Everybody won, especially the public.

JC: How did this conflict play out?

MC: In late 1972, the FCC said it was going to announce its decision. Motorola was thinking the agency was going to decide against us. We wanted to convince the FCC we were better than AT&T at making efficient use of 900-MHz frequencies. As a demonstration, Motorola created portable 900-MHz two-way radios. We mounted the radios in vans and drove Washington decision makers around so they could see and hear for themselves.

JC: What did you think of those early demonstration radios?

MC: I was enchanted by them, and so were the DC bigwigs. It wasn’t technology, it was personal. Reaction to the portable device confirmed my obsession about entering the handheld business. It was a dazzling demonstration.

JC: What did AT&T propose to do with 900 megahertz spectrum?

MC: AT&T was fixated on creating a more efficient car phone and on creating their monopoly.

JC: What did you want to do?

MC: I wanted people to experience the freedom of communicating anywhere any time. In November 1972, I called Rudy Krolopp, who had designed the first national pagers. I described my idea and told him I wanted it in the April demonstration. He said, “What’s a cellphone”?

JC: Was “cellphone” what you said?

MC: Rudy remembers it that way. I don’t remember. Maybe I said, “portable phone.” He assigned his team to design the phone. Two weeks later I bought them dinner at Lancer’s in Schaumburg, Illinois, and they presented their handmade models. One was a slider phone. One was a flip phone. A lozenge phone. One looked like a shoe. They were beautiful, all the size of a modern cellphone. We picked a simple one-piece design. Management had agreed at least to consider having a handheld phone in the April demonstration, so the research department put a dozen people onto building one. By March 1973, we had a working phone. But a cellphone by itself wasn’t of any use. The device had to make and receive calls to and from other phones.

JC: What was the absolute first call?

MC: That had to have happened in the lab, because we tested throughout, but I don’t remember when that first success happened.

JC: What was the first official public call?

MC: Our PR people had arranged for me to appear on The Today Show on Tuesday, April 3, 1973. That morning the PR lady called to say Today had bumped us. “Don’t worry,” she said. “I’m gonna get you on radio or TV or something.” And she set up a meeting for me with a radio journalist whose name is lost to history.

JC: How can that be?

MC: At that time cellular was just a concept.

The memories faded quickly. I’m glad American History is reviving them.

JC: How did you actually accomplish the demonstration?

MC: I took the reporter out on the streets of New York. We had two cell sites, one near Central Park and one on Wall Street. I decided to call Joel Engel at AT&T. I happened to have his office number on a piece of paper.

JC: Did you know the phone would work?

MC: I hadn’t tested it. I entered Joel Engel’s number and he answered! He was not fond of me or Motorola. I said, “Joel, it’s Marty Cooper.” He said, “Hi, Marty.” I said, “I’m calling you from a cellphone—but a real cellphone, a personal, handheld, portable cellphone.” Silence at the other end. He doesn’t remember this call, but I remember that he was polite.

JC: Did Joel Engel have to be in New York City for the call to work?

MC: He happened to be at his office, which was in Manhattan, but the call would have gone anywhere in the world with telephone service.

JC: Was that all that went on that day?

MC: That afternoon we had a press conference. A reporter said, “Can I call my mother in Australia?” She woke her mother up in the middle of the night. The base station was hooked to the switch, which was hooked to the public network. Joel could have been anywhere.

JC: What was the reaction?

MC: People love the future. The story ran all over the world. But the cellphone didn’t even exist; there weren’t even cordless phones. You couldn’t buy a cellphone until 1983.

JC: Why did it take 10 years to get the cellphone to market?

MC: The technology wasn’t ready. Between `73 and `83 we built at least four versions of the phone I named the “Dyna TAC.” Each one was smaller and got more manufacturable.

JC: Why push so hard to put a prototype in the public eye when Motorola had no product?

MC: To give the FCC and the Congress a picture of the future. And who created this picture? Not AT&T—Motorola. That was our reason—to stop AT&T, plain and simple.

JC: Did the AT&T executive understand when he took your call that you just put a stick in his eye?

MC: No. His view was that Motorola was really good at PR.

JC: To him it was a stunt.

MC: He may have used that word.

JC: But you also were saying to the government, “Hey, don’t give AT&T a monopoly here because we’ve got a technology that’s going to be a competitive business one day.”

MC: Yeah. Motorola was a multifaceted company and I was a daydreamer. My vision was that everybody was going to have a cellphone and we were

going to make those phones.

JC: Did something technological allow you to make a prototype that no one else had made before?

MC: Yes. There is a patent, issued to Cooper et al., that integrates all the ideas all these wonderful people that I worked with had, all these ideas lumped into one patent.

JC: What do you think of the iPhone?

MC: Steve Jobs’s vision carried Apple a long time. They are creating wonderful technology. But they’ve lost some of that vision. Or maybe folks there can’t take the kind of chances Jobs was able to take in introducing concepts that didn’t exist.

JC: Where is the industry going?

MC: Manufacturers are caught in a trend which is pretty much exhausted. The mantra has been that smaller and lighter is better, more power is better, more pixels is better, more megabits, more megahertz. It’s getting hard to find something “more” that’s useful. Technology is the application of science to create products and services that make people’s lives better. If you leave out people, it’s not technology.

JC: How many cellphones do you own?

MC: That I actually use? I guess I’ve got three.

JC: What are they?

MC: I always have the latest, hottest phone, which, in my opinion, is the Samsung S-8. I’m going to get an S-9. I should be lusting after the iPhone 10, but I’m not, because it doesn’t have any of the “people” features I find attractive. I also would have to learn a whole new interface.

JC: What are your other two phones?

MC: I have a Jitterbug. Do you know what a Jitterbug is?

JC: No.

MC: My goodness. It’s a phone optimized for seniors. My wife invented the Jitterbug and created the company that sells it. A million people use it.

JC: So, a Jitterbug and a Samsung. What’s your third phone?

MC: I have a Nokia. I wanted to understand Windows.

JC: But you don’t have an Apple phone.

MC: I had one for a while.

JC: Which?

MC: Probably an iPhone 4. I gave it to my grandson.

JC: You gave up on the iPhone.

MC: (chuckles) Yeah, I did. The only feature that I know of that really is arguably better on an Apple is face recognition.

JC: What do you love about the Samsung S-8?

MC: Everything. I love the edge-to-edge design. It’s efficient. It’s got all the apps I could imagine. It tells me where it is and when it’s charged, whether my front door is locked.

JC: How well did the cellphone match your expectations?

MC: I told you one—everybody’s got one, and needs it. Texting and talking, those things we envisioned. But cameras? We didn’t have digital cameras in 1973, nor personal computers. Nor had the internet or a large-scale integrated circuit been invented, or could you do anything at 2.3 gigahertz.

JC: Where do we go from here?

MC: The cellphone’s future is personalization and customization. Each of us is unique, and the products that make our lives easier should accommodate that.

JC: What does a cellphone look like in 10 years?

MC: It becomes what I call a server. You need something on your body connecting you to the world. But that’s a function. Now it’s not “the phone”—in fact, calling this device a “phone” is ridiculous, right? So, we’ve now got a server.

JC: But what will change?

MC: Medicine will be revolutionized. One aspect of medicine is understanding what’s going on in your body. To understand you have to measure. How do you measure unless you have devices measuring? And measurements have no function unless they accumulate where somebody can do something about them. So, the cellphone now is the medical server, and the function you measure depends on your 23andMe. If genetics says that you have a family history of congestive heart failure, you’ll have a gizmo that warns you you’re about to have a heart attack.

JC: What else?

MC: The phone will be connected to a virtual reality device. Kids will be playing what they think are games but really getting educated. So, the cellphone is an educational device.

JC: How do you regard the device itself?

MC: It’s a marvelous achievement. There are seven radios in a cellphone, each independent, with different functions. There’s a supercomputer. They claim that eventually there will be enough power in a cellphone to do all your computing; for a big screen, you’ll plug into a docking station.

JC: Do you ever think, “What have I done?”

MC: I’m an optimist. Technology does disrupt. Technology screws up a lot of people and things. But ultimately technology saves the world. Yeah, there are bad aspects of the phone but we’re going to work them out. The biggest problem in the world today is people not talking to each other.

JC: What’s the source of your optimism?

MC: I’ve got a protégé. I met this kid at the swimming pool. He says he’s going to be an inventor. “That’s interesting,” I said. “I’m an inventor.” And we are now best friends and he is inventing stuff. This kid is eight years old. And at some point, we’re going to be collaborating.

JC: What do you see as your legacy?

MC: Nobody can take the cellphone away from me, but I didn’t do that all by myself. The one I’m really proud of is Cooper’s Law. The real name is the Law of Spectral Efficiency. In its simplest form, it states that there is an exponential growth in efficiency in the use of spectrum.

JC: Explain.

MC: Around 1991 or 1992, I asked myself: On a given amount of bandwidth, how many phone calls can you make, and how many bits can you put through? I did an analysis, starting with Marconi, whose first act on radio was to place a transatlantic phone call. You can’t even measure his efficiency with that first call, but when he went commercial he was transmitting at the rate of a bit every six seconds. And you could make only one phone call in the world at a time because another telephone call in this hemisphere would have interfered with Marconi’s call. He was using all the bandwidth there was. I used that as my initial point and started finding points in time where I could measure usable bandwidth, how many people were able to talk at the same time, and so on. Since 1900, useful bandwidth, measured by how much you can pump through, has doubled every 30 months.

JC: Kind of like Moore’s Law for computer memory.

MC: It’s exponential, like Moore’s Law. We’re 10 trillion times more efficient than when Marconi started. But we also need to move lots more data. Say there’s this kid in 2030. He’s got his virtual reality goggles and he’s using ten times the access somebody is using today. That is every student in the world in 2030. You can’t have an educational system where the rich kids have virtual reality and the poor kids have nothing, but it’s going to take tons and tons of data.

JC: How do we do that?

MC: New technology makes Cooper’s Law work. But we need infrastructure. If I ran the country I’d be encouraging private enterprise. “Listen, you guys,” I’d say. “You’ve got this spectrum, and spectrum is a public resource. We’re asking you to use it right. You’re going to have to invest a lot of money. Markets will pay you for that. When it comes to education, the government will pay you to build the infrastructure.” Trump wants to build bridges and stuff. Well, equally important is this infrastructure that will eliminate poverty. Cooper’s Law will eliminate poverty. That’s my legacy.

JC: What are your hobbies?

MC: I was a runner. Now I hike. You want to know what brings me pleasure? Having ideas. The ultimate pleasure is having an original idea. Every once in a while, I come up with a zinger. H