Bryn Mawr College dropout Martha Gellhorn quit the Albany, New York, Times Union in 1930 to move to Paris and write. After 10 months of banging out ad copy and freelancing for The New Republic and other magazines, Gellhorn returned to the

Letters of Love & War 1930-1949 by Janet Somerville. Published by Firefly Books (U.S.) Inc., 2019. Text copyright © 2019 by Janet Somerville. All rights reserved.

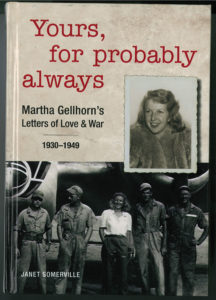

United States to undergo an abortion. Back in France with her married lover, she got pregnant again in 1933 and had another abortion. Writing for Vogue and working on a novel, What Mad Pursuit, Gellhorn traveled Europe and agonized about her affair, ultimately returning to the United States. In autumn 1934, through a journalist friend, Gellhorn got a job working for presidential adviser Harry Hopkins at the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, analyzing welfare programs. In her reports, Gellhorn embraced a lifelong determination to make “little squeaking observations about the wrongness of things.” In curating the new Firefly Books title, Yours, for probably always: Martha Gellhorn’s Letters of Love & War 1930-1949, biographer Janet Somerville presents selections from Gellhorn’s correspondence with eminent figures including Eleanor Roosevelt, Adlai Stevenson, and her first husband, Ernest Hemingway.

MG to Harry Hopkins November 26, 1934, Massachusetts

It is impossible in traveling through the state and seeing our relief set-up, not to feel that here incompetence has become a menace; and that the unemployed are suffering for the inadequacy of the administration. It seems that our administrative posts are frequently assigned on recommendations of the Mayor and town Board of Aldermen. The administrator is a nice inefficient guy who is being rewarded for being somebody’s cousin…

Now about the unemployed themselves: this picture is so grim that whatever words I use will seem hysterical and exaggerated….I find them all in the same shape—fear, fear driving them into a state of semi-collapse; cracking nerves; and an overpowering terror of the future….I haven’t been in one home that hasn’t offered me the spectacle of a human being driven beyond his or her powers of endurance and sanity.

Over dinner at the White House, arranged through her mother Edna’s acquaintance with Eleanor Roosevelt, Martha shouted at the hearing-impaired first lady about how the nation treated the poor. Eleanor stood. “Franklin, you must listen to this girl!” she cried. “She says all the unemployed have pellagra and syphilis!” Gellhorn and Eleanor Roosevelt began a lifelong friendship. In November 1934, Frederick A. Stokes Company published What Mad Pursuit to poor reviews. Her second book, The Trouble I’ve Seen, about life in the Depression, received a warm reception in September 1936.

MG to Eleanor Roosevelt, February 7, 1936, St. Louis

The Trouble I’ve Seen is being brought out in England right off (three months, I guess) with an introduction by [H.G.] Wells. It ought to get taken here sometime. Oddly, people don’t enjoy nearly as much hearing about their own woes and therefore their own responsibilities as they enjoy hearing about strangers’ messes….

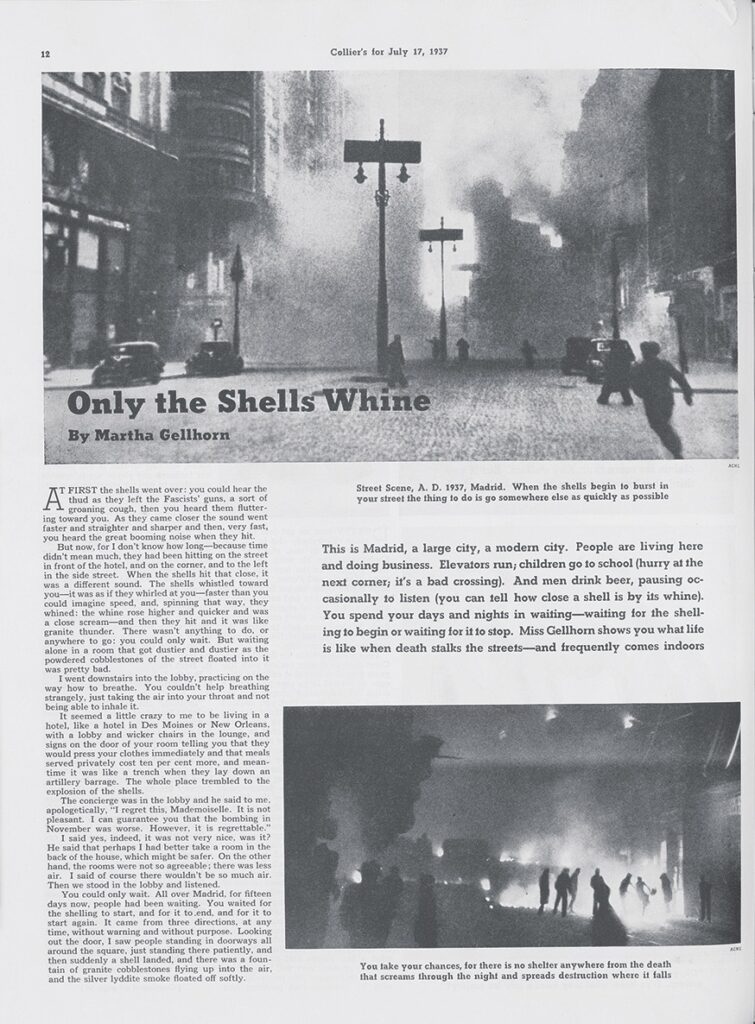

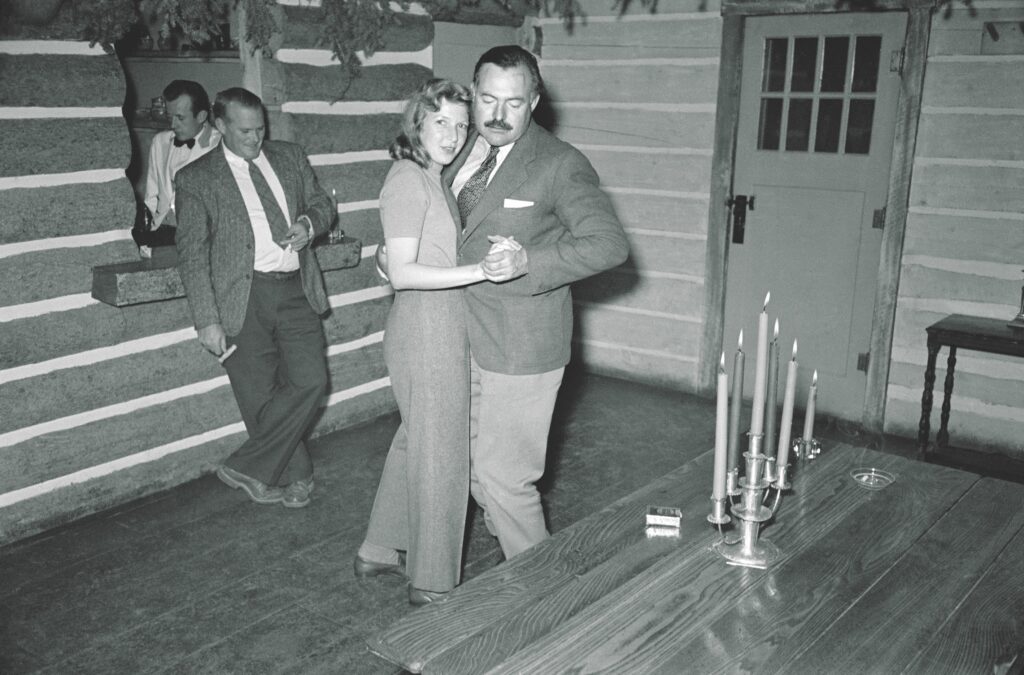

In December 1936, Martha vacationed in Key West, Florida, with her family. At Sloppy Joe’s, the Gellhorns met the bar’s most famous patron—Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway talked up Gellhorn’s story, “Exile,” to his editor at Scribner, Max Perkins, who had liked The Trouble I’ve Seen. In September 1937, Scribner’s Magazine published “Exile.” Hemingway was preparing to leave for Spain to cover the civil war. Though still married to Pauline Pfeiffer, he begged Gellhorn to join him. The best job Martha could get was as a stringer for Collier’s magazine. Hemingway took a luxury liner to Le Havre, France, before flying first class to Valencia, provisional capital of Republican Spain. Martha financed her crossing in steerage by writing a puff piece about beauty secrets for Vogue. In Gellhorn’s version of the experience, she was stranded in Paris in March 1937 without instructions from Hemingway, so she took a train to the Spanish border. Carrying a duffel bag of canned food, she crossed the Pyrenees on foot. In Madrid, Gellhorn and Hemingway shared quarters and endured shelling at the Hotel Florida.

MG’s diary, March-April 1936, Spain

[I went with Republican] brigade commander Randolfo Pacciardi down to the front….At

the front trench one of the soldiers said, “Look, there are some dead out there.” [All I could see were] two dirty bundles of grey laundry which may have been dead but when they are dead there are no long[er] men, only something finished and wasted and not good anymore and you have to think about it to feel anything, even pity.

Gellhorn and Hemingway returned to New York in May 1937 to work with director Joris Ivens on a documentary film, The Spanish Earth. In July, Collier’s published Gellhorn’s first submission, “Only the Shells Whine,” about life in Madrid. In August, Hemingway sailed again for Spain, with Martha following discreetly on another ship. For three months, Gellhorn filed stories for Collier’s and The New Yorker about the war, which was going badly for the Republicans.

MG to Hemingway, autumn 1937

I thought I knew everything about the war. But what I didn’t know is that your friends got killed.

In December, Martha returned to St. Louis for Christmas, then embarked on a grueling lecture tour advocating that Americans help the Republicans in Spain. On March 16, 1938, three days before Hemingway and Gellhorn were to sail to Europe, German bombers attacked Barcelona, killing thousands of civilians.

MG to Eleanor Roosevelt, Post-March 23, 1938, aboard RMS Queen Mary

The news from Spain has been terrible, too terrible, and I felt I had to get back. It is all going to hell… I want to be there, somehow sticking with the people who fight against Fascism. ….It makes me helpless and crazy with anger to watch the next Great War hurtling towards us, and I think the 3 democracies (ours too, as guilty as the others) have since 1918 consistently muffled their role in history. Lately the behaviour of the English govt surpasses anything one could imagine for criminal, hypo-critical [sic] incompetence, but am not dazzled either by us or France. It will work out the same way: the young men will die, the best ones will die first, and the old powerful men will survive to mishandle the peace. Everything in life I care about is nonsense in case of war. And all the people I love will finish up dead, before they can have done their work….The whole world is accepting destruction from the author of Mein Kampf, a man who cannot think straight for half a page.

Gellhorn proposed to write about the bombing of Barcelona, but Collier’s said the story was stale. Her editor instructed her to report from Czechoslovakia and England on German aggression. In August 1938, while Gellhorn was covering events in Europe, Hemingway made a final trip to Spain, writing for newspapers about the Republicans’ defeat and refugees flooding into France. In early 1939, Hemingway and Pauline Pfeiffer separated. Hemingway holed up in a hotel in Havana, Cuba, to work on a novel set in Spain during the war. Gellhorn joined him. Outside Havana she found a run-down villa called Finca Vigia (“Lookout Farm”), which Hemingway bought. Three months into World War II, Collier’s sent Gellhorn to Helsinki to cover the “Winter War” between Finland and the USSR. Finns “looked after each other’s needs and rights, with justice: a good democracy,” she wrote. Collier’s ran “Bombs on Helsinki,” which described a nine-year-old boy outside his home watching Russian bombers, holding himself “stiffly so as not to shrink from the noise. When the air was quiet again, he said, ‘Little by little, I am getting really angry.’”

MG to Ernest Hemingway, December 4, 1939, Hotel Kaalp, Helsinki, Finland

This was the first day, the first taste of war and you should have seen the Finns. They took it as if they had been seeing this every day for ten years; there was no sign of any panic….I never saw such control and discipline. It is like iron. I think it can be a very long war and I think it is possible that—unless Russia sends an army of four million against these people—that the Finns will win. They have been steadily successful to date and their pilots are wonderful….I’ll put my money on 3 million Finns against 180 million Russkis [sic]. After all, they are fighting for their lives and their homes and God alone knows why the Russians are fighting.

Gellhorn returned to Cuba in January 1940. Her novel A Stricken Field, about the German takeover of Czechoslovakia, debuted in March.

MG to Collier’s editor Charles Colebaugh, March 13, 1940, Finca Vigia, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba

It doesn’t look like there would be any Finland to go back to. …I cannot put down the disgust I feel about it….Hitler is what he is: a monster who happened in our time and was produced by it….I only wish to live long enough to see the men who have ruled Europe for the past six years destroyed. A firing squad is too good for any of them….

Gellhorn spent most of 1940 writing a short story collection, The Heart of Another. Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls came out in October; it was a best-seller. Hemingway’s divorce from Pauline Pfeiffer became final in November; he and Martha Gellhorn married on November 21. In January 1941, Collier’s sent Gellhorn to China to report on the war with Japan; a reluctant Hemingway accompanied her as far as Hong Kong. While her husband remained in Hong Kong, carousing with locals and using his celebrity to gather intelligence at President Roosevelt’s request, Gellhorn braved Japanese anti-aircraft fire to fly over the Himalayas into Burma.

In Chungking, China, Gellhorn and Hemingway lunched with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and his glamorous wife. The Chiangs cared more about maintaining their own power than defeating the Japanese and had no sympathy for China’s starving peasants, but Gellhorn’s Collier’s piece about the couple was fulsome in its praise. Later she admitted that she had soft-pedaled the Chiangs’ brutality and corruption.

MG to friend Allen Grover, July 1941, Finca Vigia, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba

Madame Chiang that great woman and savior of China. Well, balls.

Gellhorn spent most of 1942 with Hemingway in Cuba, “in the sun, safe and comfortable, and hating it.” Upon touring the Caribbean July through September, she submitted articles to Collier’s including “Messing About on Boats,” about survivors of U-boat attacks on Allied oil transports. Gellhorn began a novel, Liana, about a Caribbean love triangle involving a young Frenchman and a mixed-race woman married to a wealthy man. Liana would be her only New York Times best-seller. Gellhorn again sailed for England in October 1943. For months, while she reported on young men flying Lancasters on night bombing missions over Germany, Hemingway resisted joining her and in a string of cables accused her of abandoning him.

Ernest Hemingway to Edna Gellhorn, late 1943

I’m just so damned lonely that I feel I’m dying a little each day like a tree that has been girdled….[I] would trade my carefully taught and acquired virtue to have a wife….to love and cherish and go to bed with and talk to….and not a female war-correspondent [sic] who only comes home to get ready to go somewhere else or to write a book.

Gellhorn briefly returned to Cuba in March 1944 to find a churlish Hemingway. Jealous of Gellhorn’s success at Collier’s, he bullied the magazine’s editors into naming him the publication’s senior war correspondent in Europe, replacing Gellhorn. Bearing that credential, Hemingway snagged a seat on a Royal Air Force flight. Claiming women were not allowed on the plane—even though actress Gertrude Lawrence had been assigned a seat—he left for London, infuriating Gellhorn.

MG to Eleanor Roosevelt, April 28, 1944

The way it looks, I am going to lose out on the thing I most care about seeing and writing of in the world, and maybe in my whole life. I was a fool to come back from Europe and I knew it and was miserable about it, but it seemed necessary vis-à-vis Ernest. (It is quite a job being a woman, isn’t it; you cannot do your work and simply get on with it because that is selfish, you have to be two things at once.)….Ernest will get off to England at the end of next week. But I have been shoved back and back [on the airplane passenger list] and we don’t know whether the RAF will consent to fly me over (it’s different for Ernest) and there

I am….It’s so terribly ironical too, because I had it all worked out, just how to cover the Invasion…

Gellhorn spent 17 days sailing to Britain by convoy aboard a ship carrying explosives. She arrived May 26 to find Hemingway in a London hospital with a concussion sustained in a car accident after a party. Although Hemingway had a Collier’s credential, military authorities decided to confine the famous novelist aboard a Navy ship on D-Day. On June 7, Gellhorn beat him ashore, sneaking aboard a hospital ship and locking herself in a bathroom while the vessel crossed the Channel. She went ashore on Omaha Beach as a stretcher bearer, the first female correspondent to land in France after D-Day.

MG to Bryn Mawr lecturer and lifelong friend Hortense Flexner, London

The next day I went down to one of the embarkation ports. I saw the first prisoners arrive on the shores of England and wrote about it. They were a damn sorry master race….I went over myself the night of the second day on a hospital ship, and worked so hard I almost forgot to come up on deck and inspect the world. The wounded were very wonderful and I loved working not writing or looking, just working. I went ashore looking for wounded too and it was all sort of mad and ominous and dangerous and, in a way I can never explain to anyone, funny the way war always is funny.

Sneaking into Normandy cost Gellhorn any official status. An indignant letter to an Army officer did little to assuage her ire.

MG to Colonel Lawrence, June 24, London

As you know, General Eisenhower stated that men and women correspondents would be treated alike, and would be afforded equal opportunities to fulfill their assignments….Speaking for myself, I have tried to be allowed to do the work I was sent to England to do and I have been unable to do it. I have reported war in Spain, Finland, China, and Italy, and how I find myself plainly unable to continue my work in this theatre for no reason [other] than that I am a woman.

Lack of credentials didn’t stop Gellhorn. She buzzed from front to front, cajoling officers into letting her travel with their units and filing whenever she could charm a wireless operator into sending copy. She was in Paris at the time of the liberation in August. Finding Hemingway in Time/Life writer Mary Welsh’s room at the Ritz, she demanded a divorce.

MG to Edna Gellhorn, 1944

I simply never want to hear his name again… A man must be a very great genius to make up for being such a loathsome human being.

In May 1945, Gellhorn got a three-hour pass to visit the death camp at Dachau. “Behind the wire and the electric fence, the skeletons sat in the sun and scratched themselves for lice,” she wrote in the June 23 Collier’s. “They have no age and no faces; they all look alike and like nothing you will ever see if you are lucky.” The camp became a symbol of Nazism’s evil for Gellhorn, who had Jewish grandparents. “We are not entirely guiltless,” she wrote, “we, the Allies, because it took us 12 years to open the gates of Dachau. We were blind and unbelieving and slow.”

MG to Hortense Flexner

[I will never lose my sense of guilt because I] did not know, realise, find out, care, understand what was happening.

The late 1940s saw Gellhorn enjoy one of her few satisfactory love affairs, with U.S. Army Major General James Gavin of the 82nd Airborne Division. She wrote a novel about Dachau, The Wine of Astonishment, and adopted an Italian child. By 1954, unhappily wed to journalist Tom Matthews and living in London, she tried unsuccessfully to embrace domesticity. She continued to exchange letters with Eleanor Roosevelt, receiving news of Roosevelt’s death November 7, 1962. The next day Gellhorn turned 54.

MG to Adlai Stevenson, November 8, 1962, London

This is a day when it would have mattered to be together. To weep. All the weeping for Mrs. R. should have been done years ago, starting 70 years ago. Not for her, now she’d have never been afraid of dying and would have hated to live, ill and dependent. I always thought she was the loneliest human being I ever knew in my life and so used to bad treatment (beginning with her mother)…I never liked the President, nor trusted him as a man, because of how he treated her. And always knew she was something so rare that there’s no name for it, more than a saint….Today we can weep for ourselves. I feel lonelier and more afraid; someone gone from one’s own world who was like the certainty of refuge; and someone gone from the world who was like a certainty of honor.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, Gellhorn traveled widely, bought houses in Mexico, England, Wales, and Kenya, and struggled with loneliness. As her adopted son, Sandy, was reaching adulthood, she and he became estranged. Trips to Israel delighted Gellhorn, who championed the Jewish state and wrote without empathy about what she saw as Arabs’ self-imposed exile. She visited Vietnam and published a screed about the treatment of civilians so wrathful the South Vietnamese government refused to give her a visa for a second trip. Gellhorn hopscotched the world, looking for the best beaches for her favorite pastime, snorkeling. She became enchanted with Africa, making many visits and buying a mountainside house to be closer to her favorite animals, giraffes. At 79, on her customary walk at a friend’s house in Nyali, on the Kenyan coast, she was attacked and raped.

MG to a friend, 1988

Women have been raped all over the world since time began. Simply because I was involved does not make the case special.

On February 14, 1998, Martha Gellhorn, 89, virtually blind and racked by ovarian and liver cancer, swallowed cyanide and died at her home in London. A few days later, her brother, son, and stepson tossed her ashes into the Thames River in accordance with Gellhorn’s instructions, which ended, “…if it’s inconvenient, what the hell.”

Biographical sketch by American History senior editor Nancy Tappan.