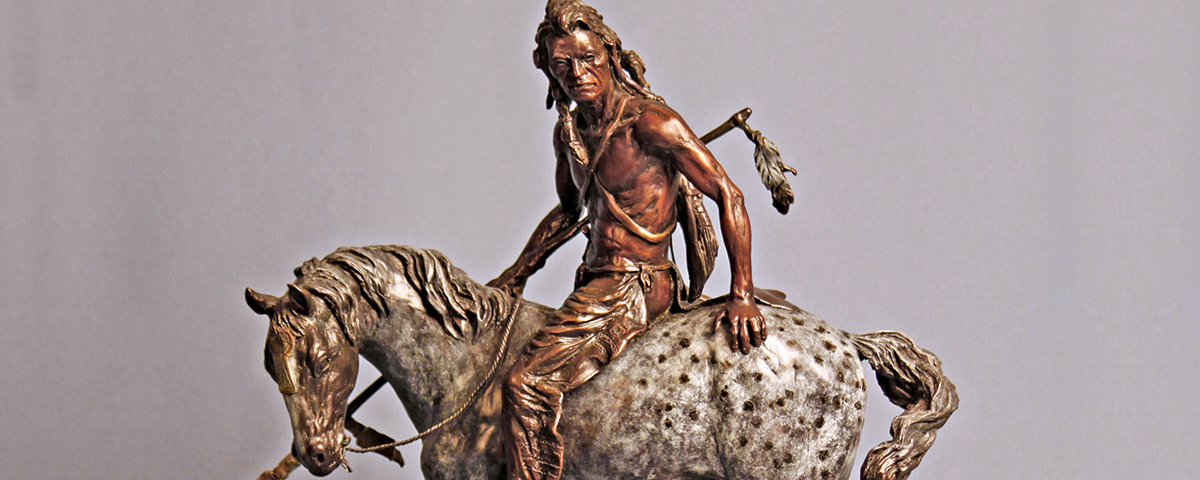

A lance-bearing Nez Perce warrior mounted on a spotted Appaloosa crosses the high plateau in the 1840s, the rider drawn to something in the distance. In 2011 when sculptor Mari Bolen rendered the 14-by-13-by-4-inch bronze Appaloosa (in an edition of 50), she hoped most of all to capture the dignity of the Nez Perce people.

“I love the looks of an Appaloosa,” says Bolen, who works from her home studio in western Montana’s Bitterroot Valley, “and the Nez Perce played a great part in the richness of the Bitterroot. Their history of trade and strong ties to the valley drew me to their culture. The flight of Joseph and his band still resonates in many stories—a beautiful people brought to an unnecessarily sad ending.”

In her half-century art career Bolen has rendered scores of her distinctive bronze figures while roaming from her native Montana to New York City, the San Francisco Bay Area, Phoenix and, finally, back to Montana in 1980. Her particular passion has been to depict “the people of the Plains nations.” Among her standout works are Eagle Dancer, the latest in her “Children of the Earth” sculptural studies of the Plains tribes, and Northern Cheyenne Warrior, one of her Plains series of almost life-size busts.

Bolen’s introduction to Western art came early in life. Her parents owned the Montana Trading Post in Great Falls, which they later renamed the B&J Trading Post. “It was in the onetime dance hall of the Mint Saloon, where Charlie Russell spent much of his time drawing, painting and sculpting,” the artist recalls. “[Mint co-owner and Russell patron] Sid Willis had a fabulous collection of Russell’s work on the walls and wax studies in long glass cases. We had a double-door pass-through to the Mint from that section of our store, and patrons were amused by the little girl perched daily on a stool in the back of the café, where I was allowed to draw or sculpt directly from Charlie Russell’s art with colored crayons and melted candle wax.

“I don’t remember not doing some sort of art,” Bolen recalls, “and I was the rebel child. When any of the old barflies would ask what I wanted to be when I grew up, I always said, ‘Charlie Russell!’ When my father died in 1959, my mother sold the store, which shortly preceded that whole half of the block being torn down to build a motel. What a loss. The Russells were sold before that to the Amon Carter Museum in Texas.”

“I’ve done massive amounts” of research, says Bolen, whose art has been shown at the C.M. Russell Museum exhibition and sale in her hometown of Great Falls, the Loveland (Colorado) Sculpture Invitational (replaced in 2014 by the Loveland Fine Art and Wine Festival) and the Sedona (Arizona) Sculpture Walk. “It’s been a lifetime study. When I feel I have enough information from enough sources—museums, libraries, tribal elders, the Internet—I can begin that particular tribe’s depiction. I just have to decide the decade, man or woman and the pose. I use hairstyles, feather placement, regalia, bead or quillwork, moccasins, weapons, etc., of a specific era or decade, and then I begin.

“The history, the true image of each person, is what I seek,” Bolen explains. “Who were these people? Where did they come from? What did they look like at this particular time? What did they wear? The ceremonies, the daily life and the stories from the old ones are part of each sculpture.

“I have thousands of photos of each nation’s faces,” she notes, “and take the most prominent features of a few from that particular tribe and meld them into one person. Most of the time the face will just happen. Of course, I do exact portraits as well, namely prominent chiefs and tribal figures from history. I am a forensic sculptor, so I look for features in the bones.”

Bolen also loves to depict wildlife. “Wildlife illustration was one of my jobs at Montana State University, where I was majoring in zoology/premed,” she says. “So wildlife has always intrigued me. Dr. Herbert Reade was writing a book on the elk and records of mortality in Yellowstone Park, and he hired me to illustrate the teeth and other parts of the anatomy. So my illustrations just turned into sculpture quite easily.”

She has plenty of opportunity to observe from life. “I live in the hills of the Bitterroot Valley, where more than 100 deer, around 40 wild turkeys, a few herds of elk, the occasional moose or bear and twice-seen cougars pass through my property. I’m especially fond of depicting bears and could watch them for hours. The Moeise National Bison Range is close by, and several ranches in the valley raise bison for meat.”

After graduation from Montana State, Bolen worked as a television, motion picture and theater art director, a packaging designer and a restoration expert. She also taught sculpture and still does, in addition to serving as president of the Montana Professional Artists Association. Among her latest works is a 6-foot-9-inch statue, commissioned by the U.S. Army, of St. Barbara, protector of artillerymen (as well as miners, architects, mathematicians, firemen, chemical engineers and prisoners). In May 2016 the artist gathered with officials at Fort Sill near Lawton, Okla., to dedicate the bronze.

Bolen shares the studio just uphill from her house with landscape artist Michele Kapor and works at all hours. “People love to spend time in the studio and often bring guests,” Bolen says. “I’ve always got some pieces in various stages of completion in clay and can explain the foundry work with some examples.”

As for leaving big-city life behind, Bolen has no regrets. “The mountains of Montana have always held my heart,” she says. “The concrete canyons had no appeal.” WW