Before the advent of aerial refueling, fuel tank capacity was the main determining factor of an airplane’s endurance. With aerial refueling, record nonstop time aloft, once measured in hours, was measured in days. The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale recognized endurance records for classes of aircraft as well as world records that transcend all classes. In 1929 the FAI also instituted a women’s class. But for examples of sheer determination and willingness to endure days and even weeks in the confines of a small airplane, nothing tops the progression of world records for time aloft with refueling.

In 1921 wing-walker Wesley May performed the first known aerial refueling as a stunt. May, along with pilots Frank Hawks and Earl Daugherty, accomplished the feat by carrying a five-gallon can of gasoline on his back as he moved from one plane to the other.

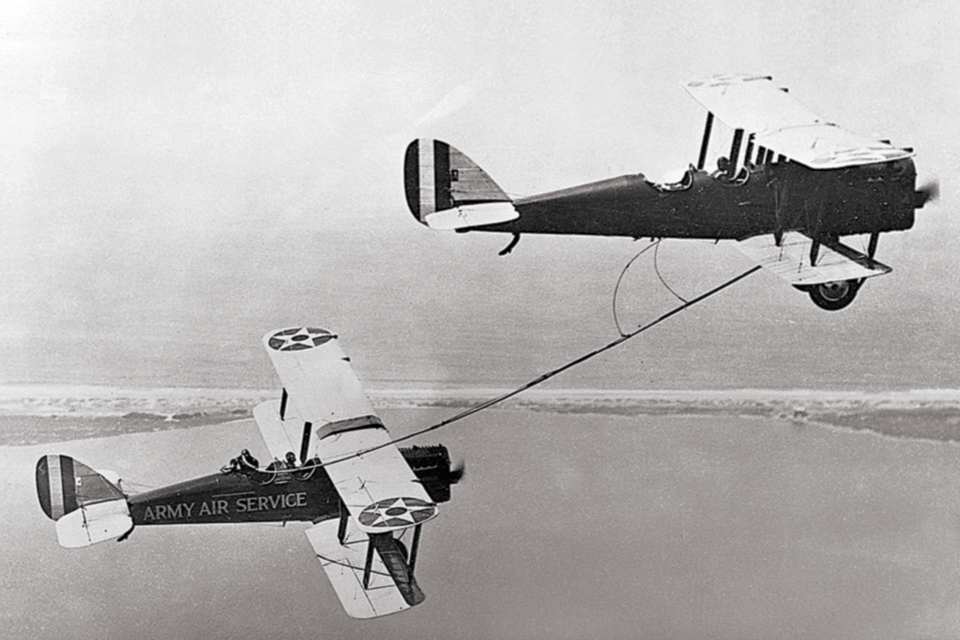

The first practical aerial refueling took place on June 23, 1923, when U.S. Army Air Service crews transferred fuel via a hose between two Liberty DH-4Bs flying from Rockwell Field in San Diego. The next day’s mission allowed the receiver plane to stay airborne for 23 hours and 48 minutes. Then, on August 27-28, Captain Lowell Smith and 1st Lt. John Paul Richter remained aloft for 37 hours and 15 minutes with refueling, breaking the nonrefueled record of just over 36 hours. Smith and Richter’s record held until June 1928, when Adjutant Louis Crooy and Sergeant Victor Groenen of Belgium stayed airborne for 60 hours, seven minutes in a refueled de Havilland DH-9.

The most well-known early endurance flight was that of the Army Air Service’s Atlantic-Fokker C2A trimotor Question Mark, from January 1 through 7, 1929, over Van Nuys Airport in California. Question Mark was crewed by Major Carl Spatz (later changed to Spaatz), Captain Ira Eaker, 1st Lt. Harry Halverson, 2nd Lt. Elwood Quesada and Sergeant Roy Hooe, all of whom would go on to distinguished military careers. The men remained in the air for 150 hours and 40 minutes. Though the U.S. military did not pursue aerial refueling at that time, the publicity surrounding the flight prompted a rush among civilian pilots to establish endurance records, with about 40 attempts made and four new records set in 1929.

Reginald Robbins and James Kelly departed Meacham Field on May 19 in a Ryan B-1 Brougham monoplane christened Fort Worth. Unlike the Army pilots, these men were relative amateurs—Robbins a former cowboy and Kelly a former railroad mechanic. To maintain the engine, Kelly ventured out on an eight-inch-wide catwalk twice a day and greased the rocker arms. The two remained aloft for 172 hours, just over seven days. “If anyone beats our mark, we’re going up again,” Kelly said after the flight. But it was only a matter of weeks before their record fell, and Robbins and Kelly never did reclaim the record.

A month later, Roy Mitchell and Byron Newcomb stayed airborne over Cleveland in a Stinson Detroiter for 174 hours, from June 28 to July 6. To keep their engine running, the pair devised a system to grease the rocker arms through lines that came into the cabin.

While Mitchell and Newcomb were still circling Cleveland, Loren Mendell and Roland Reinhart took off on July 2 from Culver City, Calif., in a Buhl Airsedan dubbed Angelino, returning to earth on July 12 after a record 246 hours and 43 minutes in the air. No sooner had they landed, however, than Dale Jackson and Forest O’Brine launched a record attempt from St. Louis in a Curtiss Robin on July 13. The pair shattered Mendell and Reihhart’s briefly held record, remaining aloft for 420 hours, 17 minutes—more than 17½ days.

Nearly a year after Jackson and O’Brine’s record, on June 11, 1930, John and Kenneth Hunter took off from Chicago’s Sky Harbor Airport in the Stinson SM-1 Detroiter City of Chicago, and didn’t touch ground for 23 days, one hour and 41 minutes. While John and Kenneth piloted City of Chicago, brothers Albert and Walter flew the refueling and resupply plane, and their mother and sister helped with ground operations. The brothers had remained low-key about their flight due to a failed attempt a year earlier, but as the days aloft rolled by they made national news. Will Rogers even rode in the refueling aircraft. Though the brothers serviced the engine by climbing outside the plane using handholds and a narrow catwalk, they were forced to land when an oil screen in the engine became clogged. Upon landing, thousands of people were on hand to greet them.

The Hunters’ record would stand for five years until another set of brothers, Al and Fred Key of Meridian, Miss., took off on June 4, 1935, in a borrowed Curtiss Robin named Ole Miss. The Key brothers’ record attempt was made possible by contributions in money and services from local residents and businesses. In order to reduce the inherent hazards of aerial refueling, A.D. Hunter devised a system for them that allowed hands-off refueling and incorporated a check valve in the hose to prevent fuel spills. Local welder Dave Stephenson built an extensive catwalk so Fred could service the uncowled engine in flight, and Frank Covert made a special fuel tank that replaced all three seats. James Keeton used his own Curtiss Robin for resupply, performing 435 refuelings. For the final refueling, the crewman who operated the air-to-air system was absent, so airport porter Germany Johnson stepped in and performed flawlessly. After 653 hours and 34 minutes in the air, the brothers landed to a cheering crowd of more than 30,000 people. (In 1955 the restored Ole Miss was donated to the Smithsonian for permanent display, and today it hangs in the National Air and Space Museum’s Golden Age of Flight gallery.)

The Key brothers’ record held until October 1939, when Wes Carroll and Clyde Schlieper took off from Marine Stadium in Long Beach, Calif., in a float-equipped Piper Cub called Spirit of Kay. After the water takeoff, the men circled over Seal Beach and the desert, where they took on fuel and supplies from an automobile. While one of the men flew the plane low over the speeding 1935 Ford convertible, the other man reached down to retrieve supplies and cans of fuel handed up to him. They didn’t set foot on the ground for 726 hours—30 days and six hours. In a Piper Cub!

World War II put endurance flights on hold. It wasn’t until March 1949 that two pilots in an Aeronca Sedan named Sunkist Lady topped Carroll and Schlieper’s record. After three previous attempts, Dick Riedel and Bill Barris of Fullerton, Calif., took off on March 15, 1949, and headed east for their historic flight. They flew to Miami, and were refueled and resupplied at selected airports along the route. A ground crew flying ahead of Sunkist Lady loaded a waiting Willys Jeepster at each resupply location. Riedel and Barris flew low over the speeding Jeepster to retrieve fuel and supplies. After reaching Miami, they loitered in the air for 14 days as they waited for the weather to clear along their route back to California. Upon their return on March 11, they circled the skies ticking off the hours, touching down on April 26 after 1,008 hours, two minutes in the air, or 42 days.

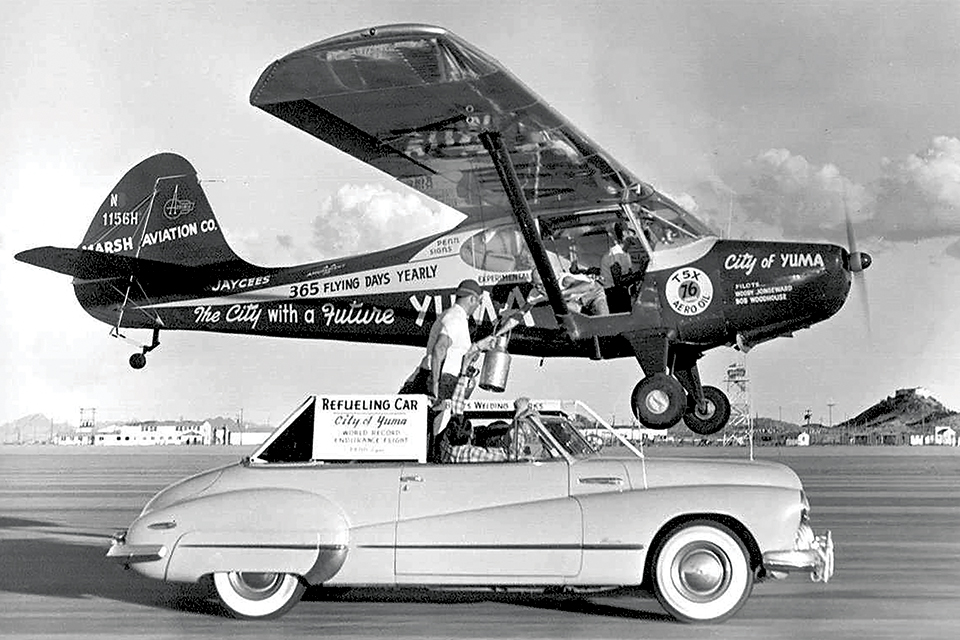

As amazing as the 42-day record was, it didn’t last long. After their first two attempts were cut short due to mechanical problems, Bob Woodhouse and Woody Jongeward departed Yuma, Ariz., in the Aeronca Sedan City of Yuma on August 24, 1949. The flight was intended to prompt the government to reopen Yuma Army Airfield, which had been closed after WWII. Since Riedel and Barris had remained aloft for 1,008 hours, the new goal was 1,010 hours, or “ten-ten,” which became the name of the refueling car, a 1948 Buick convertible. During their flight, the pair were interviewed on national newscasts over their two-way radio. People wanted to know the details of how they managed to eat, sleep and, most important, go to the bathroom. “We had these double bags, and I would always joke that we’d fly over California and throw it out,” Jongeward explained. The men took four-hour shifts at the controls, and two or three times per day would return to the Yuma airport for resupply from the speeding Buick.

Woodhouse and Jongeward passed the 1,010-hour mark and continued on until October 10: ten-ten. They landed after 1,124 hours and 17 minutes in the air—nearly 47 days. “The time of the landing came on Woody’s shift,” said Woodhouse. “He was a little worried because we hadn’t landed in seven weeks and we had knocked a spotlight or two off of the side of the Buick and bent the hubcap all up on the airplane.” Nevertheless, they landed successfully and succeeded in getting the Yuma airfield reopened. In 1959 the field became Marine Corps Air Station Yuma. The Aeronca and a Buick of the same model are now displayed in Yuma City Hall.

Woodhouse and Jongeward’s record stood for nine years until Jim Heth and Bill Burkhart stayed aloft for 1,200 hours and 19 minutes—50 days—over Dallas. They took off in their modified Cessna 172, The Old Scotchman, on August 2, 1958. The men refueled twice a day from a truck speeding down the runway of Dallas Redbird Airport, lowering a rope to retrieve gas cans and supplies. They landed on September 21. Surprisingly, their record would be challenged only a couple of months later.

Isn’t 50 days stuffed into a small plane with another person long enough? Apparently it wasn’t for Robert Timm and John Cook, who spent 64 days, 22 hours and 19 minutes together in a Cessna 172 while circling the desert Southwest from December 4, 1958, to February 7, 1959. The flight was intended to generate publicity for the Hacienda Hotel in Las Vegas, whose owners encouraged promotional suggestions from the staff. Timm, who worked as a slot machine repairman and had served as a WWII bomber pilot, suggested the endurance flight.

The Cessna prominently displayed “Hacienda Hotel” in large letters on each side of the fuselage. Besides publicizing the hotel, the flight raised money for the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

During the first three attempts, lasting as long as 17 days, mechanical problems forced the plane down early. Timm didn’t click with his original copilot, and replaced him with John Cook, an A&P mechanic. The new donated Continental engine, which had proved problematic, was also replaced with the original 450-hour engine. Modifications to the 172 included a 95-gallon Sorenson belly tank, an accordion-style folding copilot’s door, a four-by-four-foot foam pad in place of the co-pilot’s seat and plumbing that came through the firewall to allow inflight oil changes.

The two men took off from McCarran Field at 3:52 p.m. on December 4. To verify that they did not secretly land during the flight, officials in a car speeding down the runway painted white stripes on the tires as the plane flew just above them.

A Ford truck with a fuel tank and pump in the back refueled and resupplied the aircraft. The Cessna would meet the truck on a closed section of road in the desert near Blythe, Calif. An electric winch lowered a hook to snag the refueling hose, and one of the men filled the belly tank while standing outside on a retractable platform. It took about three minutes to fill the tank.

Time finally began to take a toll on the men and machine. “We had lost the generator, tachometer, autopilot, cabin heater, landing and taxi lights, belly tank fuel gauge, electrical fuel pump, and winch,” Cook wrote in his journal. The engine gradually lost power as carbon built up on the plugs and in the combustion chambers. Disaster nearly struck on the night of January 9, their 36th day aloft, when Timm fell asleep at the controls over Blythe and awoke more than an hour later to find the Cessna flying through a canyon on autopilot.

After they finally landed, Cook said, “There sure seemed to be a lot of fuss over a flight with one takeoff and one landing.” During their nearly 65-day flight, the pair had covered more than 150,000 miles, equivalent to about six times around the world. The record-setting Cessna 172 now hangs in the terminal at Las Vegas’ McCarran International Airport.

Timm and Cook’s accomplishment likely marked the end of marathon endurance flights in airplanes. Does anyone really want to spend more than 65 days circling the countryside, eating, sleeping, bathing and using the toilet while shoulder-to-shoulder with someone else? Odds are slim. And the FAI no longer recognizes new endurance records due to safety concerns.

Early-aviation enthusiast W.M. Tarrant is the author of East to Meet the Enemy: A Novel of World War One Aerial Combat. Further reading: The Longest Flight: Yuma’s Quest for the Future, by Shirley Woodhouse Murdock and James A. Gillaspie.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!