The woman Levanch [sic] L. Swart, who claimed to have been married to my late husband Edward Z.C. Carroll Judson, he always said was not his legal wife. She blackmailed him and did a great many things to annoy him and came here to Stamford after we were married and in fact wanted me to give her my husband’s invalid chair after his death.…She was a bad woman, deep and designing in her motives—a dangerous woman. —Anna Fuller

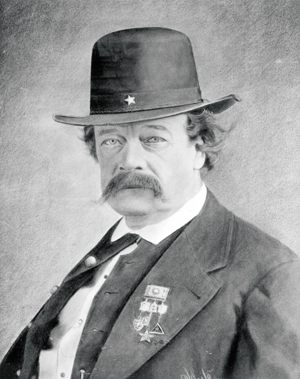

Soon after Edward Zane Carroll Judson—better known to posterity as dime novelist Ned Buntline, a pseudonym he gave himself in 1844—died on July 16, 1886, his wife Anna Fuller was outraged to learn that two of his ex-wives had applied for his Civil War pension. Yet confusion over which spouse had rightful claim to the money was understandable, as the notorious and prolific “Father of the Dime Novel” and self-proclaimed creator of “Buffalo Bill” had married at least nine times. He had never formally divorced several of his spouses and, indeed, hadn’t even bothered to tell some he was leaving. The battle over his pension stretched from the day of his death all the way through 1908.

Born in Stamford, N.Y., in 1822 or 1823, Judson ran away from home in his preteens and soon secured a commission as a midshipman in the Navy, beginning the first of many real and highly fictionalized adventures he’d later build on in his popular novels. During his writing career Judson was also a temperance lecturer, though he was often drunk when delivering his sermons. Judson’s serialized novel Buffalo Bill, the King of Border Men, play Scouts of the Plains and subsequent dime novels featuring Buffalo Bill Cody catapulted the latter from obscure Army scout to national celebrity.

Judson was responsible for creating a highly romanticized and often misleading image of the American West, albeit one the masses back East clamored to read in the mid- to late 19th century. Scholars estimate he wrote at least 400 dime novels over his career and perhaps as many as 600. His plotlines, if unimaginative, remained consistent: abduction, pursuit, rescue, re-abduction, re-pursuit, re-rescue, with multiple sets of villains. But as editor R. Clay Reynolds notes in his 2011 compilation of Buntline dime novels, “The tales of Judson’s several marriages would make for a better story than he ever wrote.”

Judson was responsible for creating a highly romanticized and often misleading image of the American West, albeit one the masses back East clamored to read in the mid- to late 19th century

According to biographer Jay Monaghan, Judson met his first wife, Severina Marin, in Havana, Cuba, during carnival season in 1839. She was the daughter of a prosperous Catalonian family from St. Augustine, Fla., and the couple was married by a justice of the peace in nearby St. Johns on Dec. 18, 1841. Severina was 20; Judson was 17. In the fall of 1867 the Republican Banner of Nashville, Tenn., printed a bizarre account of Judson’s wife:

There died in the poorhouse of this county, and was buried last Saturday at the expense of the public, a woman who was at one time the wife of the famous Ned Buntline and at another the mistress of Ben McCulloch, the Texan Ranger.…Buntline, before he came to Nashville and was involved in a fearful tragedy that is associated with his name, lived a thriftless, daredevil life in Texas, on the prairies, upon the Gulf Coast and about New Orleans.…His meeting with the pretty cigar girl was an accident, and his suit was long and difficult. At last he had to marry her, and three weeks after the marriage the couple suddenly disappeared.

The “fearful tragedy” refers to events following Judson’s seduction of a married woman in Nashville in 1846. That March 14 the woman’s husband, Robert Porterfield, tracked down Judson, shot at him three times and missed; the writer shot back and killed the husband. A mob of angry townspeople tried to lynch Judson, but the rope broke. Authorities took him into protective custody and later released him, as Porterfield’s survivors brought no charges. The “obituary” for the wife Ned was with around the time he seduced Mrs. Porterfield continues with details of the woman’s slow descent from life as a young bride and Ranger’s mistress to that of a gambler and then a prostitute and pauper.

In all probability, though, this was not Severina Marin. The article identifies the woman as Maria Cordova—believed to be Judson’s second wife—though it notes she’d been using various pseudonyms for some time. In her testimony regarding Judson’s pension, his fifth wife, Lovanche Swart, recalled her husband had told her about Severina and mentioned she’d died within a year of their marriage. Several 1849 news accounts claim Severina had died in Nashville six years earlier, “having suffered much from his conduct toward her.” In fact, she had died in Smithfield, Ky., in 1846.

On Jan. 23, 1848, Judson married his third wife, 19-year-old Annie Abigail Bennett, in lower Manhattan’s historic Trinity Church. She divorced him on Sept. 29, 1849, on grounds of “ill treatment” and “infidelity.” New York’s World newspaper printed all the salacious details provided by witnesses at the couple’s divorce proceedings, one policeman testifying that he’d often spotted Judson visiting a “house of ill fame” and keeping company with prostitutes. Yet the 1850 U.S. census shows Judson lodged with Bennett and her family well after her divorce was granted. In her pension testimony Swart said that shortly after they had met in 1853, the author showed her a clipping from a London paper reporting Bennett had died. In fact, Bennett was very much alive, although she did remarry and move to Europe.

In late 1851 Judson saw an opportunity to unite pro-slavery Northerners and Southerners in their common desire for territorial expansion—not to mention a way to make a tidy profit for himself. He yoked himself to Venezuelan filibuster Narciso López, who fomented a military expedition to Cuba to overthrow Spanish colonialism and thus open the island to annexation by the United States as a new slave state, much like what had happened in Texas. Judson, living in New Orleans at the time, sold Cuban scrip and lectured on “liberty in Cuba” and “Americanism at home,” sentiments shared by the flowering Know Nothing political movement, which opposed immigrants and Catholics. Buntline was a party member. When López was captured by the Spanish that fall and executed in Havana, his expedition dissolved, and Judson wisely hurried west to avoid those holding the now worthless scrip. He boarded a steamboat bound for St. Louis, where he tried to hawk his latest book, Ned Buntline’s Novelist. It flopped, but the entrepreneur soon lit on another moneymaking scheme as a theater producer. After training a quartet, designing a few costumes and printing up playbills, he led his little company aboard a steamboat—a cheap way to tour villages along the Mississippi, Missouri and Illinois rivers. Perhaps, too, a way to meet women, as on April 20, 1852, in Hannibal, Mo., Judson married his fourth wife, Margaret Ann Watson, from McDonough County, Ill.

In all likelihood Judson was either drunk, hiding from St. Louis authorities or both when he wedded Watson. Some two weeks earlier he’d ridden down that city’s crowded streets and fired several shots into crowds of election day voters, instigating a riot that resulted in several deaths. The incident harked back to his actions during the notorious Astor Place riot in Manhattan three years earlier, for which he’d served a year in prison. Judson had sparked this second riot to steer people away from ballot boxes and hopefully benefit his friend Whig Mayor Luther Martin Kennett. It worked, and Kennett won re-election, though authorities eventually tracked down Judson and arrested him for mayhem. Friends bonded him out of jail, and a few days later he failed to show before a judge. That fall, safely across state lines in Illinois, Judson started a political journal named Buntline’s Novelist and Carlyle’s Prairie Flower. The venture failed within months, as did his marriage to Watson. He went back to New York, and she remarried some years later.

The record of Judson’s marriage to Josie Judah notes it was his third — at least three shy of his true nuptial tally to date. Noting a discrepancy, the Charlestown Advertiser accused Judson of bigamy

In July 1853 Judson became acquainted with Lovanche L. Swart, the recent widow of the man who printed the author’s intermittent periodical Ned Buntline’s Own. Swart lived with her parents and young son in Chappaqua, 30 miles north of midtown Manhattan. Years later Swart told a Stamford (N.Y.) Mirror reporter she had married Judson on Sept. 24, 1853, in Hoboken, N.J., in a house he purportedly owned. “We lived there until sometime in April 1854,” she said, “when he started out lecturing on ‘Americanism’ and organizing lodges, about the commencement of the Know Nothing party, taking me with him. We went through the Eastern states, had good times and enjoyed life in all its pleasures.” However, in August 1854, during their stay in Boston, Judson became entangled with Jewish actress Ione “Josie” Judah and abruptly abandoned Swart at their hotel. Having no income, the spurned spouse moved back to her father’s home in upstate New York.

Judson married Judah on June 13, 1854, in Charlestown, Mass. He was 31; she was 18. The record of the marriage notes it was Judson’s third—at least three shy of his true nuptial tally to date. Noting a discrepancy, the Charlestown Advertiser accused Judson of bigamy, reporting he had married “a lady in Newark” the previous September, recently abandoned her and then clandestinely married Judah. “When the first wife came to ‘see about it’ on the 27th June,” added the paper, “he had fled with his new wife to parts unknown.” They soon returned to Boston.

A record of Judson’s split from Judah remains elusive, but presumably they parted ways shortly after the marriage. If the bride was heartbroken, she was at least prepared from prior experience to deal with it. Judah’s father and two brothers drowned in a shipwreck off the coast of Florida in 1839, her mother Marietta remarrying and moving to San Francisco. One of Judah’s sisters launched her own successful vaudeville career, while another raised three daughters (Josie’s nieces) who sang and danced their way to fame as the Worrell Sisters, among the best-known sibling acts of the late 19th century. In 1903 a New York theater historian reflected briefly on the Judah family, singling out Ione as “a great spiritualistic medium.”

Meanwhile, Swart, having moved back into her parents’ upstate New York home, got work as a seamstress. Despite the economic straits and embarrassment heaped on her by Judson, she kept up a correspondence with him for more than a year. “After that,” she told the Stamford Mirror, “we occasionally met, up to the year 1859, and his habits were such that I had very little to do with him,” referring to his drinking. In 1863 she bumped into Judson unexpectedly on the streets of New York City, and he asked to visit her. “He looked pale, haggard and nearly worn out, only weighing 96 pounds,” she recalled. “He said he had come home to die and could not do so without a reconciliation. I doctored and nursed him.” Judson told his erstwhile ex he was on furlough from his cavalry unit, and he wanted to marry her again, as their first marriage “would not hold good according to the laws of New York State.” And so, on January 14, at Swart’s home on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, the couple was “legally, morally and religiously married” by her Episcopal minister before several witnesses.

In her April 1881 tell-all in the Stamford Mirror Swart recalled her wayward husband toyed with her emotions and finances over the next eight years. He traveled more extensively than ever before, adapting his stock adventure plots to the American West. While doing so, he met handsome young scout and buffalo hunter William Frederick Cody and wrote the first of many fantastically popular dime novels about him. It was Judson, the story goes, who gave Cody the moniker Buffalo Bill. When the author was in New York, he visited Swart two or three times a week, bringing cash, gifts, flowers, even a canary—and, of course, his amorous attentions.

Swart admitted she’d felt placated, setting aside any and all threats of divorce—that is, until Oct. 10, 1871, when she opened the Stamford Mirror to find the week-old marriage notice of Judson and one Anna Fuller. Swart’s mother immediately wrote to a reverend at the church where Judson and Fuller married, who confirmed the vows and said he had raised concerns with his colleagues and the latest bride’s family. “I did all I could to put Mr. Fuller’s people on their guard against Mr. Judson,” he told her, “as I had intimations that he had other wives living. If your daughter is his legal wife, some of her friends should put the law in force against him, on the charge of bigamy.” According to both Judson and Swart, the pair continued to meet on occasion over the next few years, although they had differing recollections about those meetings. The seamstress claimed she only made contact when Judson was in arrears on payments toward her upkeep; Judson insisted Swart was a deranged woman continually seeking to extort money from him, and that she “chased him through the streets and wrote notes to him.” He said he had nothing she could get a hold of and told her “to go ahead or to the devil.”

Swart and Fuller in turn may have been still legally married to Judson when he wed yet another woman. Catharine “Kate” Myers. was born in 1837 and lived in Chappaqua. Judson and Myers were married by a Methodist Episcopal preacher on Nov. 2, 1860, in Ossining, N.Y. The couple had four children. Their eldest, Mary Carrollita, was born on Jan, 10, 1862, at Eagle’s Nest, Judson’s rustic cabin in the Adirondack Mountains (Hamilton County). After two subarctic winters, however, Myers decided she’d had enough and returned to Chappaqua to live with an aunt.

If Myers felt squeamish about giving birth at Eagle’s Nest, she would have every right to, as yet another of Judson’s wives had died there in childbirth just a couple of years before. Eva Marie Gardiner was just 17 when Judson hired her from a Troy beer hall to be his housekeeper and 18 when he married her. Gardiner was only 19 when she and her baby died on March 4, 1860. According to Monaghan, Ned buried Eva with the baby “in a rude coffin under the wet ground behind the log house.”

Myers divorced Judson on Nov. 27, 1871, about eight weeks after he had married Fuller. According to later interviews with Myers’ children with Judson, the author was mostly sober and domesticated when at home and even “downright scared” of her. Biographer Harold Hochschild reported that a knife-wielding Kate had once locked her husband in a closet, leaving him to huddle shamefacedly as visitors called, and that more than once she had driven him from the house. Still, Myers must have had at least some anxiety about her husband’s fidelity, as evinced by a remark in one of his letters to her. “I have been wild & crazy, have wandered far,” he wrote in September 1866, “but never have been untrue to you.”

Fuller, the wife who remained with Judson till death, drew on recollections of Cody to establish the marital solidarity the couple enjoyed during the last years of his life. “We traveled together on his lecture tours, covering a period of near two years, then we traveled near two years with William F. Cody,” she testified. “After about 1876 he [Judson] settled down here in Stamford in our home and remained here till he died. I always went with him on his lecture tours and while he was with William F. Cody.” After collecting more than 500 pages of testimony from ex-wives, friends, family members and military cohorts of Judson’s, the special examiner for the U.S. Bureau of Pensions ultimately ruled in Fuller’s favor, awarding Judson’s annuity to her and their one surviving child. Separately, officials in Delaware County, N.Y., allowed her to keep their residence, also named Eagle’s Nest, the only property of value left in Judson’s estate after years of overspending. Had the Bureau of Pensions scrutinized one more piece of evidence, the outcome may have been different: The 1880 U.S. census shows Judson living in Manhattan—with wife Lovanche Swart. WW

Los Angeles–based independent historian Julia Bricklin is the author of America’s Best Female Sharpshooter: The Rise and Fall of Lillian Frances Smith (reviewed in the December 2018 Wild West) and is writing a book about Ned Buntline. For further reading she recommends Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory and Popular History, by Joy S. Kasson, and The Hero of a Hundred Fights: Collected Stories from the Dime Novel King, from Buffalo Bill to Wild Bill Hickok, by Ned Buntline, edited by R. Clay Reynolds.