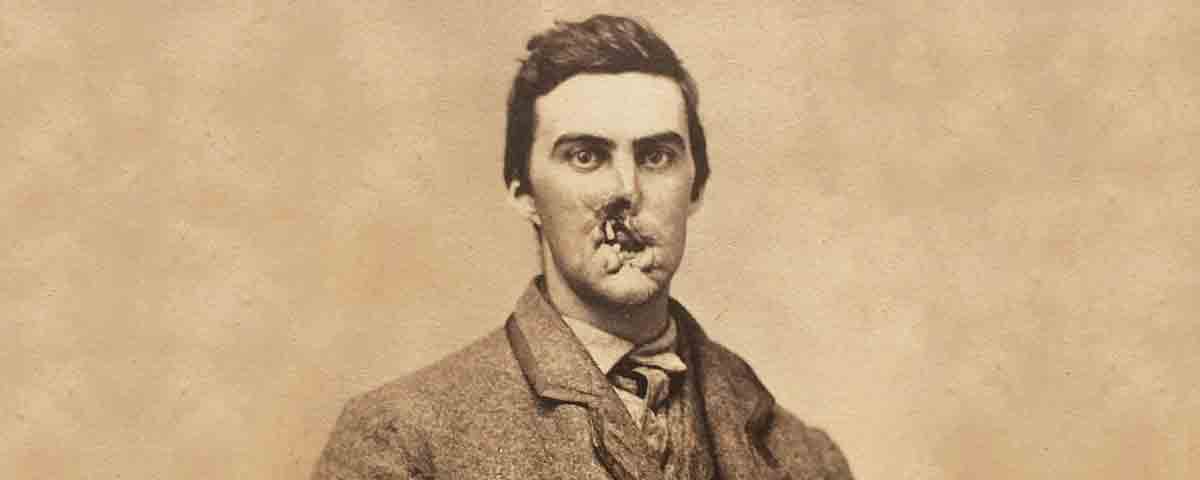

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] year after his regiment’s ill-fated charge at Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, Oliver Dart Jr. faced another great trial, sitting for a photograph at a studio on Main Street in Hartford, Conn.

The resulting carte de visite, found in the 14th Connecticut veteran’s pension file in the National Archives, is difficult to view. Bundled in a heavy coat, the blue-eyed veteran with black hair and thick eyebrows stares at the Kellogg Brothers’ photographer. A mangled lower jaw, mouth, and nose—the awful effects of a shrapnel wound suffered during the attack on Marye’s Heights—are obvious. How Dart summoned the fortitude to sit for the CDV, undoubtedly evidence for his pension claim, is remarkable.

As he waited for his turn to be photographed that day, Dart’s mind may have drifted off to the Battle of Fredericksburg. The 14th Connecticut was part of the 2nd Brigade, which included the 108th New York and the 130th Pennsylvania, in Brig. Gen. William F. French’s 3rd Division of Maj. Gen. Darius Couch’s 2nd Corps. The Nutmeggers crossed the pontoon bridges into Fredericksburg on December 12 and spent the evening bivouacked in shell-torn and ransacked houses. The next day, French’s division was ordered to make one of the first attacks against Marye’s Heights. Marching onto the battlefield via Princess Anne Street, the 14th Connecticut came under “a most galling fire” after crossing a causeway over a canal near the railroad depot. The regiment was ordered to lie down before beginning their attack.

Even before the regiment rushed forward to try to overwhelm the Southern battle line at the base of Marye’s Heights, it had to endure a storm of Confederate artillery fire that, according to Company B Lieutenant Henry Goddard, “blackened the air for hours.” Regimental historian Charles Page wrote that “the belching of two hundred pieces of artillery seemed to lift the earth from its foundation, shells screeched and burst in the air among the men as if possessed with demons and were seeking revenge…”

One of those iron demons fired from high ground on the 14th Connecticut’s right burst among the prone soldiers in Company D. A 3- by 2-inch fragment smashed into the ground, firing sand into the eyes of 14th Connecticut Corporal John Symonds and blinding Private Dart’s brother-in-law. Then the deadly chunk of metal crashed into the arm and face of the 23-year-old Dart, before striking a 4-inch square wooden fence post. Corporal Charles Lyman, lying next to Dart, recalled years later that the fragment surely would have ripped through his head and killed him had it not struck that obstacle. When Sergeant Benjamin Hirst of Company D saw Dart’s wounds, he was aghast. “Poor Oliver Dart,” he said. “As he rolled over he looked as though his whole face was shot away.”

The unfortunate private was one of 92 men of the regiment wounded at Fredericksburg, along with 10 killed, and 20 missing. Dart was carried to a divisional hospital at the Rowe House on Sophia Street, where Henry Stevens, the 14th Connecticut’s regimental chaplain, was horrified by the carnage. “On the northern porch lay, among others, our Dart, his face torn off as though slashed away with a cleaver,” Stevens recalled, “and by his side lay Symonds, his eyes swollen with inflammation to the size of eggs, the sand grains showing through the tightly stretched and shining lids.”

On the day after Christmas, Dart was admitted to Stanton General Hospital in Washington, one of scores of military hospitals in the capital city. His chances of recovery were considered slim; “wounded in battle,” a doctor there wrote, “probably mortally.” When his older brother George, a farmer, visited Oliver at the hospital, he found conditions there deplorable. After five weeks in the Washington hospital, Dart was mercifully discharged from the Union Army and sent home to South Windsor. Miraculously recovering, he underwent an operation on his face at the home of his older brother, James. Oliver, the youngest of the six children of Amanda and Oliver Dart Sr., underwent a second procedure on his face at the home of his father in South Windsor.

“George Dart and his wife were almost constantly with their injured brother,” a postwar account noted, “and gave him every care and attention.” For three months in the summer of 1863, Oliver also spent time at a soldier’s home in Hartford, where he received sustenance from a special cup because of his terrible face wound.

In June 1863, Oliver filed for divorce from his second wife, Maria, claiming “a total neglect of all duties of marriage.” Nearly three years later, the divorce was granted. (Maria was the sister of John Symonds, the soldier who was wounded next to Oliver at Fredericksburg.)

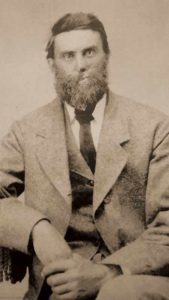

In December 1863, Dart filed for a government pension; the application was approved, and he initially received $8 a month. In 1869, Oliver married his third wife, Aurelia Barber, with whom he had his only three children. In an attempt to cover up his grievous war wounds, he grew a bushy beard and mustache.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The deadly chunk of metal crashed into the arm and face of the 23-year-old Dart[/quote]

“In time he recovered,” the postwar account noted, “though the wound was always visible and in later years his mind was somewhat affected, undoubtedly due to the shock and the suffering that ensued from the injury.”

Life remained an almost constant struggle for the Civl War veteran. Dart was struck down with a case of consumption in the summer of 1879. Only 40 years old, he died on August 11. He was buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Vernon, Conn., next to first wife Emily, who died in 1860, and Aurelia.

Connecticut resident John Banks works for ESPN. He is the author of Connecticut Yankees at Antietam, maintains John Banks’ Civil War Blog, and is secretary-treasurer of The Center for Civil War Photography. He wishes to thank Alan Crane, who discovered the Dart CDV in the National Archives.