[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne of the U.S. Army’s finest and most successful World War II combat commanders is one of the war’s most neglected generals. Because Lucian K. Truscott Jr. toiled in Sicily and Italy—both largely forgotten campaigns—and because he lacked the appetite for publicity, despite appearing on Life magazine’s cover, commanders who served in the European Theater eclipse Truscott.

The square-jawed, rough-hewn Truscott possessed all the qualities needed for success on Earth’s deadliest place: the modern battlefield. He had toughness, courage, tactical ability, and professional competence. He also had an intangible only the best possessed: great leadership under fire—the genius for doing what must be done in the heat and chaos of battle that separates the adequate from the exceptional. Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower knew what he had in Truscott; in 1945, Eisenhower rated Truscott as his most able army commander, second only to General George S. Patton.

“He was absolutely fearless,” recalled Truscott’s son, Lucian K. Truscott III—a West Pointer who commanded an infantry rifle company in Korea and an infantry battalion in Vietnam. Lucian III was referring to his father’s polo game, where fearlessness “gave him an advantage over many opponents who would eventually back off a little when he pushed them too far. And he played to win, for sport and exercise too, but mainly to win.”

Truscott brought the same philosophy to war. “Listen, son, goddamnit,” he once counseled young Lucian. “Let me tell you something, and don’t ever forget it. You play games to win, not lose. And you fight wars to win! That’s spelled W-I-N! And every good player in the game and every good commander in a war, and I mean really good player or good commander, every damn one of them has to have some sonofabitch in him. If he doesn’t he isn’t a good player or commander. And he never will be a good commander. Polo games and wars aren’t won by gentlemen. They’re won by men who can be first-class sonsofbitches when they have to be. It’s as simple as that. No sonofabitch, no commander.”

Lucian King Truscott Jr. was born in Chatfield, Texas, in 1895 and raised in Oklahoma under hardscrabble conditions. His lifelong raspy voice resulted from accidentally swallowing carbolic acid as a boy. Life magazine war correspondent Will Lang called it Truscott’s “rock crusher voice,” and it only enhanced his persona.

Truscott dreamed of attending West Point, but knew his chances for an appointment were slim. At 16, he quit school to become a teacher, claiming to be 18—the minimum age required for a teaching certificate. For six years he taught school in the small town of Eufaula, Oklahoma, before joining the army. Pancho Villa’s 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico, and the war in Europe provided opportunity in the form of a new program to enlarge the army and recruit officers outside the usual channels. In 1917 Truscott, 22, secured a provisional commission as a cavalry lieutenant.

Truscott spent 1917 to 1918 training in Arizona. He took up polo in the early 1920s while stationed in Hawaii with the 17th Cavalry. By the mid-1930s, as a four-goal handicapper on the army polo team, he had become legendary for his fierce competitiveness and reckless disregard for his safety.

Truscott bore a striking resemblance in appearance and manner to another cavalryman and fierce polo player—George S. Patton, Truscott’s senior by 10 years. Both were profane around troops, uncompromising, and fervently despised all foes. “Be aggressive, be tough. When you strike the enemy, aim to kill and destroy,” Truscott told his men. “Take your objective at all costs….Give the enemy no pause. Destroy him!”

In 1942, Truscott was assigned to England as army liaison to Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Combined Operations Headquarters. After observing British commandos, he pushed to create a kindred U.S. Army force he named “Rangers” and selected a rising army star, field artillery major William O. Darby, to command the unit.

Truscott was the primary American observer at the disastrous August 1942 Anglo-Canadian raid on the German-occupied port at Dieppe, France. While most viewed the amphibious operation, which incurred enormous losses in men and materiel, as a failure, Truscott saw Dieppe as a lesson in war that the Allies had to learn—in this case the hard way.

By November 1942 Truscott was a major general, commanding a task force under Patton as part of Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa. A few months later, he was running the advance command post at the Allied front in Tunisia. He reported directly to Eisenhower, then commander of Allied Forces Headquarters in North Africa, as Ike’s eyes and ears. Truscott’s outstanding performance led to his April 1943 appointment to command the 3rd Infantry Division for the July 1943 invasion of Sicily.

Eisenhower visited the division in Tunisia in late June. “From every indication it is the best unit we have brought over here,” he wrote to General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army chief of staff. “Truscott is the quiet, forceful, enthusiastic type that subordinates instinctively follow. If his command does not give a splendid account of itself, then all signs by which I know how to judge an organization are completely false.”

Familiarity with the debacle at Dieppe and the fledgling American army’s stumbles in Tunisia led Truscott to hold the division to a tough regimen. “I had long felt our standards for marching and fighting in the infantry were too low,” he wrote in his 1954 war memoir, Command Missions. “Not up to those of the Roman legions nor countless examples from our own frontier history, nor even those of Stonewall Jackson’s ‘Foot Cavalry’ of Civil War fame.”

Rigorous physical training raised the division’s march speed to four miles an hour, greatly outpacing the infantry standard of two-and-a-half miles per hour. Doing the “Truscott Trot,” most of his infantry battalions could hit five miles an hour, combat loaded. In Sicily this capacity paid huge dividends: like modern-day Roman legions, the 3rd Division marched the length and breadth of the island under grueling conditions. When Truscott’s infantrymen advanced more than 100 miles from Agrigento to Palermo over treacherous terrain in only three days, one general observed, “What Truscott did in Sicily was to turn his infantry into cavalry.”

Truscott’s men feared and admired him. As a result of his leadership and extraordinary far-sightedness, the division’s reputation improved along with its performance. He engendered such loyalty that more than one officer refused promotion to keep serving with him. But behind the rugged image and harsh philosophy, Truscott was an unfailingly modest man almost contemptuous of his personal image. “He seems to have been as unflamboyant a leader as has appeared in the history of the U.S. Army since Ulysses S. Grant,” eminent British historians Dominick Graham and Shelford Bidwell—both combat veterans—wrote.

Truscott was unafraid to challenge superiors, Patton included. During the 3rd Division’s advance on Messina, Patton and Truscott argued over the timing of an amphibious end-run along the island’s northern coast. Truscott stood his ground. “If you don’t think I can carry out orders, you can give the division to anyone you please,” he told Patton. “But I will tell you one thing, you will not find anyone who can carry out orders which they do not approve as well as I can.” Any other commander would likely have relieved him on the spot, yet the incident quickly passed. Patton not only declined to sack Truscott but had a drink with him.

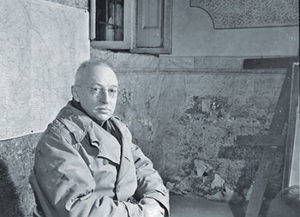

Truscott had idiosyncrasies, including a deep superstition about clothing. He habitually wore a white scarf from an airman’s escape kit that featured a map of the fighting area. He donned the first one in Sicily after acquiring it as a present, using the piece of neckwear so often to protect his nose, mouth, and raspy throat that it became a trademark. Each campaign brought a new scarf, bearing an escape map of the region being contested. Truscott also wore a battered brown leather jacket, and strapped a GI-issue .45-caliber semiautomatic pistol to his waist. And he considered his ancient pink cavalry breeches and fragile knee-high cavalry boots “lucky.” Whenever he wore them enemy shelling seemed to stop as if by divine command. Truscott also had an aesthetic side. Through the war, four Chinese-American cooks and valets tended him. He allowed no one else to prepare his meals and his attendants made sure the mess table was always topped with a vase of fresh flowers.

In September 1943, the 3rd Division landed at Salerno, Italy, after the beachhead was secured, joining the Allied Fifth Army’s slow grind north through some of the world’s harshest fighting terrain. Truscott’s fearlessness was on display a few weeks later during a difficult crossing at the Volturno River, just north of Naples. He was decorating a colonel who was also an old friend when German artillery shells began falling close by. “I can think of no finer way of presenting this decoration than under battle conditions,” Truscott said. Then he growled, “Now what are you going to do about this goddamn situation on the river? Goddamnit, your men will be in trouble if you don’t get some armor over to help them.”

Another incident at the Volturno illustrated his talent for improvising at the front. Seeing engineers erecting a pontoon bridge in support of a regiment that had already crossed the river in rubber rafts, Truscott noted tanks idling behind a tree line, waiting for the bridgework to be completed. He bounded from his jeep and began banging on the tanks until their commanders’ heads appeared. “Goddamnit, get up ahead and fire at some targets of opportunity,” he growled. “Fire at anything shooting at our men.” The tankers hastily complied.

In January 1944, hoping to outflank fanatical resistance that was stalling the Allies’ advance around Monte Cassino, the high command decided on a risky flanking action at the seaside town of Anzio. VI Corps, reconstituted as an Allied expeditionary force, landed on January 22. Initially, resistance was light, but attempts to push inland soon ran into serious opposition. The German commander in chief in Italy, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, rushed massive reinforcements that thwarted the Allied advance on key high ground—the Alban Hills—and stood to prevent the capture of Rome, 35 miles from Anzio.

VI Corps lacked the strength to take Rome or advance far inland without exposing its flanks to counterattack. Anzio quickly turned into siege warfare. In savage and bloody battles eerily reminiscent of World War I, the sides locked in a deadly struggle for survival. The Allies hugged a narrow semicircular beachhead against German forces determined to drive them into the Tyrrhenian Sea. The battles that resulted are unique in World War II history; there was no distinction between frontline and rear-area troops. Everyone was under threat from long-range German artillery that pounded the beachhead day and night.

Allied positions began to unravel during a massive German counteroffensive codenamed Fischfang (“fishing”) that began on February 16. The moment called for extraordinary leadership—which beachhead commander Major General John P. Lucas was not delivering. Lucas—who rarely left his underground headquarters in Nettuno, east of the beachhead—had grown increasingly pessimistic. He failed to inspire confidence, particularly among the British, who saw him as weak and ineffectual. Eventually his superiors viewed Lucas the same way, sealing his fate.

The Fifth Army commander, Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, turned to Truscott, assigning him as deputy commander of VI Corps. Dismayed at having to give up his beloved 3rd Division to play second fiddle in an assignment with no command authority, Truscott was only briefly bitter. “This was certainly no time to consider personal preferences,” he wrote later. “There was a job to be done, and I was a soldier. I could only carry the order out loyally.”

Six days later, on February 22, Clark relieved Lucas and appointed Truscott VI Corps commander. Truscott had three daunting tasks: find a way to keep the beachhead secure, reassure British leadership, and eliminate the corps command post’s bunker mentality.

Truscott acted quickly. Despite a severe case of laryngitis, he visited every unit in the Anzio beachhead within 24 hours—a practice he continued, routinely coming under enemy fire. Unlike Lucas he worked and lived above ground. In his war room, he hung an enlarged copy of a Bill Mauldin cartoon showing scruffy GIs Willie and Joe in a mud-filled Anzio foxhole. “Th’ hell this ain’t th’ most important hole in th’ world,” the caption says. “I’m in it.” The message that things were different soon got through to corps staff, who reacted favorably to Truscott’s tough command.

Exposed to British customs in his days at Mountbatten’s headquarters in 1942, Truscott began inviting British officers to his quarters for drinks, conducting a great deal of serious business. Truscott also often visited their units. His aide, Captain James M. Wilson, recounts how while at one observation post, Truscott and a British division commander cautiously crawled up to observe the front, where they encountered heavy machine-gun fire. “As they came tumbling down, each lost his helmet,” Wilson recalled. “In the ensuing confusion each ended up with the other’s helmet on his head, much to the amusement of the Tommies.” The hostility Lucas had triggered among the Brits vanished.

Truscott also worked the press. “Gentlemen, we’re going to hold this beachhead come what may,” he told war correspondents. Wrote British reporter Wynford Vaughan-Thomas: “And he stuck out his jaw in a way that convinced you that any German attack would bounce off it.”

With the Allies holding the beachhead by a thread, Truscott prepared VI Corps for a May 1944 breakout. His lucky boots had become too fragile to wear daily. The offensive went badly at first and seemed to worsen when Truscott had a jeep accident. His staff fretted over Truscott’s broken rib and injured legs. And, as Will Lang wrote in his October 2, 1944, Life magazine profile, “there was also concern because of reports that he couldn’t get his boots back on. Embarrassed, admitting this was a silly way for grown men to act, his officers approached and asked him if he couldn’t try just once more to get his lucky boots on. Truscott groaned into them. The offensive succeeded.”

German opposition began to collapse as VI Corps broke free of the Anzio beachhead, poised to capture Rome. Truscott had victory within his grasp when Clark committed the Italian campaign’s gravest blunder. Instead of seizing Rome and punishing the retreating German Tenth Army, Clark ordered Truscott to halt his offensive, switch the main effort northwest of the Alban Hills, and advance on Rome from that direction.

Clark’s order “dumbfounded” him, Truscott said later, and “turned the main effort of the beachhead forces from the Valmontone Gap and prevented the destruction of the German X Army.” Clark’s decision forced Truscott to fight in the most heavily defended sector, costing his force time and men, and delaying the capture of Rome.

As VI Corps finally reached Rome’s outskirts, Truscott again courted death—this time from a German machine gun in an outhouse. He was reviewing a map with Major General Ernest N. Harmon, commander of the 1st Armored Division, when the gunman opened fire. “This, I thought, was the ultimate anticlimax,” Harmon recalled. A nearby Sherman tank simply veered across the field, crushing the building. “When the tank had finished, there was neither machine gun, outhouse nor German.” Harmon said. “Truscott and I picked ourselves up, resumed the tattered vestments of our dignity and went back to being generals again.”

A few days after the liberation of Rome, Mark Clark assigned Truscott and VI Corps to Operation Dragoon, the August 1944 invasion of southern France. Before Truscott left Italy, Pope Pius XII granted him an audience. “It was not a bad rise for a poor boy from frontier Oklahoma,” Truscott proudly wrote to his wife.

Truscott’s service with VI Corps ended in September 1944 when he was promoted to the three-star rank of lieutenant general and reassigned to command the newly activated Fifteenth Army in the United States. But Italy was not yet in his past; in December, when Clark succeeded British general Harold Alexander as commander of Allied troops in Italy, Truscott was given command of Fifth Army. He led that force through the difficult battles in northern Italy that lasted until the German surrender in May 1945.

On May 30, Memorial Day, Truscott traveled to a new American military cemetery at Nettuno that was full of Anzio dead. Unlike today’s beautifully maintained facility, the 1945 edition was a raw, muddy, unfinished place with wooden temporary grave markers. VIP visitors included several American senators. Cartoonist Bill Mauldin was also present to witness an extraordinary ceremony.

As the general who had commanded Allied troops at Anzio, Truscott, 50, was the primary speaker. When introduced, he stood, turned his back on the VIPs, and addressed the graves of the men he had commanded.

No text of the speech exists; the fullest account is Mauldin’s. “The general’s remarks were brief and extemporaneous,” the artist wrote. “He apologized to the dead men for their presence here. He said everybody tells leaders it is not their fault that men get killed in war, but that every leader knows in his heart this is not altogether true.”

Rough voice rising over the graves, Truscott said he hoped anyone interred there through any mistake of his would forgive him, but knew this was asking a lot. He said he would not speak of “glorious dead” because he didn’t see any glory in getting killed in your late teens or early twenties. He promised that if he ever ran into anybody, especially old men, who thought death in battle glorious, he would straighten them out; it was the least he could do.

“It was the most moving gesture I ever saw,” Mauldin recalled later. “It came from a hard-boiled old man who was incapable of planned dramatics.”✯