During the last half of December 1861, allegations were buzzing about Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s uncontrolled drinking. No one was sure who started the malicious rumors. Perhaps it was some of the crooked contractors and suppliers who wanted to retaliate because Grant was thwarting their schemes to defraud the government. Perhaps the stories were planted by detractors who second-guessed Grant’s decision in November to pick a fight with Confederates at Belmont on the Missouri side of the Mississippi River across from Columbus, Ky. Whoever was responsible knew resurrecting suspicions about his drinking would strike him where he was most vulnerable. The commotion precipitated a mini-flurry of correspondence—three letters from three people—urging an uncovering of the facts and ascertaining if the general might prove too incapacitated to carry out duties at his district headquarters at Cairo, Ill. In succession the correspondents were: an alarmed businessman who alerted a congressman who aroused a staff officer who, in turn, assured the congressman. All three of the correspondents, as well as the subject of their correspondence, had ties to Galena, Ill., a town in the lead mining region of northwest Illinois.

The businessman was Benjamin H. Campbell, originally from Virginia and residing since 1835 in Galena. A prosperous merchant and owner of a packet line doing trade on the upper Mississippi River, Campbell had just returned from a trip to St. Louis where worrisome stories circulated about Grant. On December 17, he sent a letter to his congressman with dire news: “I am sorry to hear from good authority, that Gnl Grant is drinking very hard, had you better write to Rawlins to know the fact.”

The congressman, Republican Elihu Washburne, had come west and in 1840 settled in Galena where he became a prominent lawyer and was elected in 1852 to his first term in Congress. He was a flinty, ascetic New Englander by birth, who neither drank, smoked, nor chewed, who spurned attendance at theatrical performances, and who was a foe of any swindler out to hoodwink the U.S. government. Washburne was also an intimate of President Lincoln—so close that when plots against President-Elect Lincoln’s life forced a change in his train schedule through Baltimore, Washburne was the only one to greet him at the Washington railroad platform. The congressman was understandably interested in these drinking rumors because earlier in the year he was influential in having fellow Galena resident, Grant, included in the first batch of newly minted brigadiers appointed from Illinois. Immediately upon receipt of Campbell’s letter, Washburne dashed off his own on December 21 to Captain John A. Rawlins, Grant’s assistant adjutant general in Cairo, requesting an explanation.

Rawlins was also a Galena lawyer—he had lived in or nearby Galena all his life—and the town’s most prominent Democrat. It is telling that, despite their differing political perspectives, Rawlins was the person Washburne should first consult. He knew well of Rawlins’ patriotic fervor, that he was steadfastly abstemious, and a man of unquestioned probity and uncompromising values. If Grant were tippling, Rawlins would know, and it would not sit well with him. However, Washburne’s letter “astounded” Rawlins, and he took several days before penning his reply, which was a lengthy and impassioned defense of his commanding officer.

Rawlins made several points in his letter, among them: a categorical denial of Benjamin Campbell’s statement about General Grant’s hard drinking (“ut[t]erly untrue and could have originated only in malice”). A tally of virtually each of the few instances in which alcohol in strictly modest amounts touched Grant’s lips since Rawlins had joined him at Cairo (e.g., “on one or two occasions he drank a glass of [champagne] with his friends”). Testimony to Grant’s resolute attention to the duties of his command (e.g., “Ever since I have been with Genl. Grant he has sent his reports in his own hand writing to Saint Louis daily when there was a matter to report”). And an allusion to scurrilous cheats who wanted to strike back at Grant and cause him injury (“That General Grant has enemys [sic] no one could doubt, who knows how much effort he has made to guard against & ferret out frauds in his District”).

Rawlins ended the letter with a heartfelt self-disclosure and then a pledge to Washburne: “No one can feel a greater interest in General Grant than I do; I regard his interest as my interest, all that concerns his reputation concerns me; I love him as I love a father, I respect him because I have studied him well, and the more I know him the more I respect and love him.” What Rawlins is disclosing here is his devotion to Grant and how he has come to regard Grant as a man worthy of his personal investment. This is meant to reassure Washburne that he, Rawlins, is a man who has Grant’s best interests—which are his interests as well—at heart. It is not hero-worshipping; nor is it Rawlins viewing Grant as a father figure. It is definitely not Rawlins engaging in a repudiation of his own father for his

presumed shortcomings.

In closing, Rawlins pledged “that should General Grant at any time become an intemperate man or an habitual drunkard, I will notify you immediately, will ask to be removed from duty on his staff (kind as he has been to me) or resign my commission.” There would be no coverup by Rawlins if Grant wavered. When he vowed to be Washburne’s eyes and ears in the field, he was not making an empty promise: Rawlins was almost like a divining rod in detecting the presence of ardent spirits in camp and, as he showed in this letter, he could recite chapter and verse of each instance when Grant hoisted a glass.

To his credit, Rawlins shared his reply with Grant before sending it to Washburne. There would be no colluding with a congressman behind Grant’s back. Moreover, this written show of support helped assuage some of the mortification Grant was feeling as a result of the spurious allegations. A grateful Grant pored over the letter, then nodded his assent, “Yes, that’s right; exactly right. Send it by all means.”

Rawlins’ powerful letter succeeded in defusing this threat to Grant’s character and fitness to command. It wasn’t the first threat, and there would be more.

The story of John Aaron Rawlins is intertwined with the history of Galena and the man, Ulysses S. Grant, whom he loyally served as assistant adjutant general, chief of staff, and finally secretary of war. Grant had lived in Galena for a year before the Civil War commenced. There he came into contact with a number of men, and after receiving a general’s commission, he invited several of them to complement his staff. These were men with whom Grant felt comfortable and whom he could trust, Rawlins above all. Regarding his feelings for Rawlins, Grant in later life revealed in his Memoirs, “I became very much attached to him.” Years earlier in a letter to Congressman Washburne, he shared his opinion regarding Rawlins’ capabilities as an officer:

Rawlins especially is no ordinary man. The fact is had he started in the Line there is every probability he would be today one of our shining lights. As it is he is better than probably any other officer in the Army who has filled only staff appointments. Some men, to[o] many of them, are only made by their Staff appointments whilst others give respectability to the position. Rawlins is of the latter class.

Rawlins performed a host of invaluable tasks for Grant besides writing reports and handling and organizing his files and documents. These included issuing orders for Grant, serving as his emissary on certain delicate missions, offering input on strategy decisions as well as staff business, and possessing the vehement assertive qualities in making personnel and policy choices that his confrontation-averse commander avoided. Rawlins’ value to Grant as confidant, administrator, adviser, and loyal staffer cannot be denied. Colonel Ely Parker, Grant’s military secretary who knew both men dating back to prewar Galena, once told Washburne that Rawlins was “absolutely indispensible [sic] to General Grant….I am also very confident that General Grant’s continued success, will, to a great extent, depend upon his retaining General Rawlins as his privy counsellor or right hand man.”

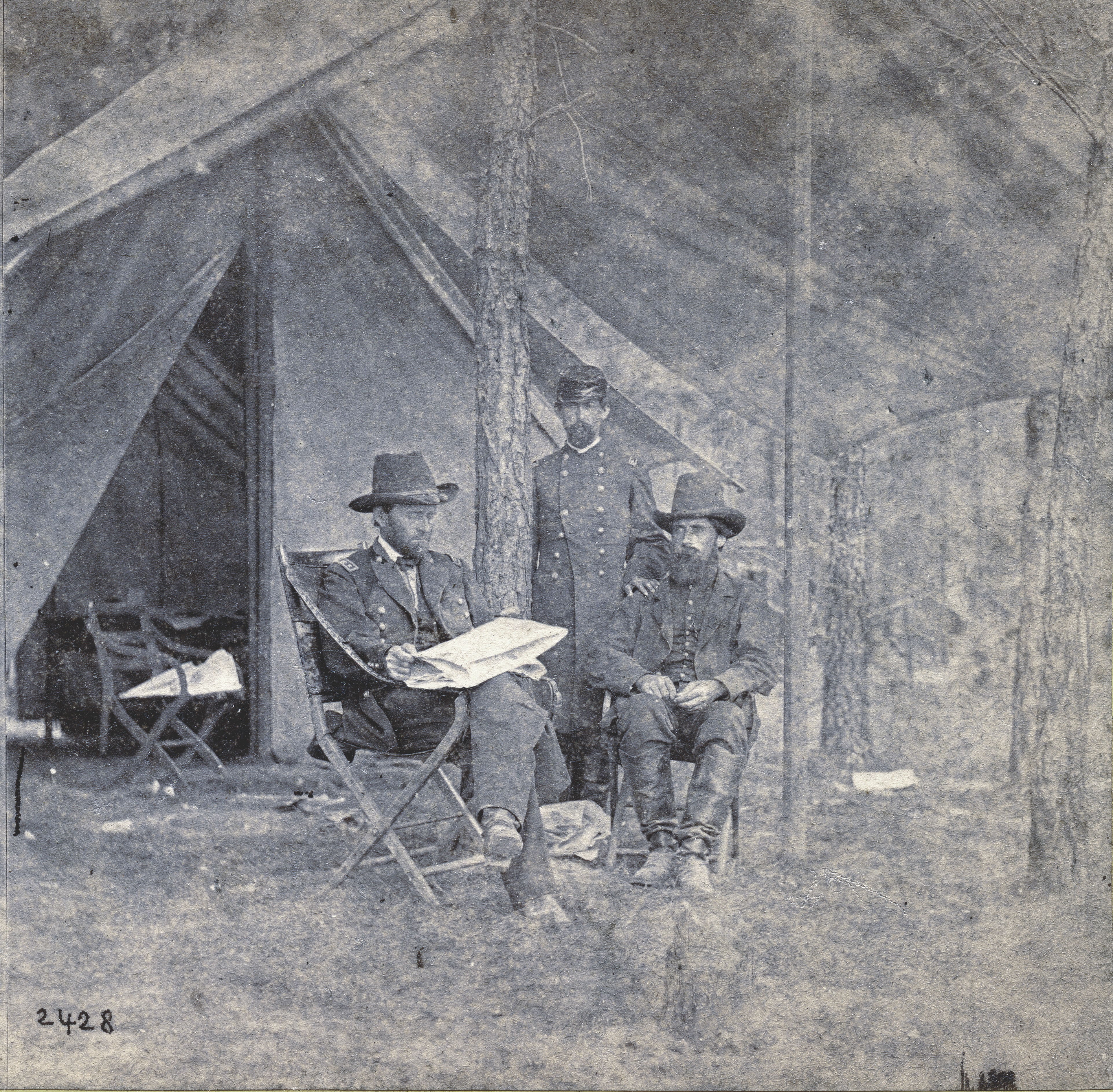

Although Rawlins is not well-known today, he was a near constant presence at Grant’s command headquarters. Theirs was a trusted friendship as well as close working relationship. As historian E.B. Long noted, “They were quite inseparable during much of the war, and this was undoubtedly not entirely because of their relationship in the army command.” Regarding how connected they were, Long went on, “When one studies and records the rise of Grant through the winter of 1861–1862, through the capture of Fort Donelson, the controversial Battle of Shiloh, the area command in the summer of 1862, and the early abortive but important moves against Vicksburg, one is studying simultaneously the career of John Aaron Rawlins.”

However, to many Rawlins is known as Grant’s protector—the staffer who insulated him from untrustworthy aides, grafters, and fellow general officers who wished to promote themselves at Grant’s expense—or as the adviser who functioned as an alter ego, that is, providing a counterbalance to some of Grant’s natural tendencies: where Grant eschewed conflict, Rawlins had no trouble expressing his displeasure or laying down the law, and where Grant could be trusting at times to a fault, Rawlins’ initial inclination was often to be suspicious of motives. Rawlins’ reputation as the scold who kept Grant sober is unwarranted.

Grant, the general, did drink on occasion during the war—and he did not hold his drink well—but rarely to excess and not in a way to blemish his record. Much more often, the problem of Grant’s drinking revolved around the stories that circulated about his overfondness for alcohol and gossip about the trouble it brought him during his pre-Civil War military career; those rumors and doubts hung over him like a cloud and made for ammunition that could be used by men who disliked him or who could profit if he failed. Given that reputation, Grant operated as if under a microscope: Were his military decisions made while under the influence? Were troublemakers abetting his taste for alcohol? At every social event at which drinks were served, attendees kept close watch to see (and often report) if he abstained or imbibed.

John Rawlins did not control Grant’s drinking—it could be argued that he did not need a nag or scold to maintain his sobriety while fighting Confederates. But Rawlins provided two things that benefited Grant: the shield of a “temperance zone” that enveloped Grant and a loyalist’s zeal. The presence of a temperance zone reassured Grant’s supporters (“If Rawlins is policing the camp, it must be as dry as the Sahara”) and kept critics at bay. Rawlins as the loyal staffer ran stout downfield interference to keep Grant moving to the goal line. Whether Rawlins proved more helpful to Grant as protector/alter ego than as a hard-working adjutant/chief of staff is open to debate. Grant would have agreed more with the latter.

Despite Grant’s expressed appreciation, fondness, and respect for John Rawlins, it remains a mystery why Grant only made mention of Rawlins three times in his famed Memoirs. Perhaps it was a simple omission on Grant’s part; or intentionally done to keep from stirring up old stories about Rawlins as his protector. At the time of the publication of the Memoirs, mutual friends struggled to explain the oversight and found it hurtful to Rawlins’ memory. Ely Parker was one such mutual friend who felt for Rawlins and wondered if the omission could be attributed to Grant harboring a grudge against Rawlins for having supposedly opposed William Sherman’s campaign through Georgia and even going to Washington behind Grant’s back to sabotage it. Parker expressed his feelings to John C. Smith, then lieutenant governor of Illinois and a fellow Galenian:

[Rawlins] certainly did conspicuous and meritorious services to his Chief and his country as A.A.G. [Assistant Adjutant General] and Chief of Staff. He builded [sic] and saved much for which no credit is awarded him. No one could have been more true and loyal to his Chief and country than he, and yet he gets only faint praise from Grant in his Memoirs…he almost charges him with disloyalty to himself, an imputation, which, even if true should have been omitted or not referred to….It was, in my judgment, a grave and serious error, which the true friends of both will never cease to regret. If Rawlins was opposed to Sherman’s campaign to the sea, it was from conscientious motives with no desire or intent to thwart Grant in his plans or wishes.

In truth, Rawlins did have some initial misgivings about Sherman’s plan, misgivings that had ample face validity. He did not play the role of an obstructionist, however, and it was not his style to do an “end run” around his superior. Rawlins’ gesture to share with Grant the letter he sent to Washburne illustrates that point.

Rawlins and Grant established a geographical connection at Galena, a river town in a mining region that produced a bevy of politicians, jurists, wealthy entrepreneurs, high-ranking military officers, and memorable personalities far out of proportion to its size. John Rawlins was one of Galena’s most revered sons. He spent his first 30 years or about three-quarters of his brief life in Galena and surrounding Jo Daviess County, rarely venturing beyond its borders. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Rawlins was a rising political and professional figure. He was a successful lawyer and civic leader who towered over the reticent and generally reclusive Grant. But before achieving prominence, Rawlins was a product of the Jo Daviess hills, its hardwood forests, meandering streams, and rich mineral deposits. He burned the wood to produce the charcoal that smelted the ore that yielded fortunes in pig lead. To a generation of townspeople, John Rawlins was known as the “Galena Coal Boy.” He ended his life as Grant’s indispensable man.

Al Ottens is Emeritus Professor of Counselor Education and Supervision at Northern Illinois University, and past president of The Manuscript Society. He has written several articles for the society’s quarterly journal, Manuscripts, on Civil War topics, including “Forging Loyalty: The Curious Case of Williamson R.W. Cobb,” the story of perhaps the earliest known forgery of Abraham Lincoln’s signature.