Samuel F. Perkins was only 27 in January 1911 when the called him “the greatest authority in the world on man-carrying kites.” Los Angeles Herald Eighteen months earlier nobody had ever heard of the newly minted MIT graduate. What happened during that year and a half to land Perkins on the front page of most every major American newspaper is a strange and unusual story.

Right out of college, Perkins took a job working for Thomas C. Baldwin, the “father of the American dirigible,” who was touring the United States demonstrating his airship. Perkins may have signed on as Baldwin’s factotum, but he soon proved adept at saving the day. Whenever unruly winds prevented Baldwin from launching his airship, Perkins entertained the impatient crowds by flying his home-built, banner-draped kites until the weather improved. Though his kites were still unmanned at that point, he was gaining valuable experience in how to control them under various conditions.

While he and Baldwin toured New England, Perkins had the opportunity to demonstrate his kite-flying skills to President William H. Taft. He didn’t get his big break, however, until September 1910 at the Harvard-Boston Aero Meet. Sponsored by Perkins’ alma mater, the aviation meet was the first of its kind on the East Coast. The Boston Globe even offered a $10,000 cash prize for the fastest flight from Atlantic, Mass., to Boston Light and back.

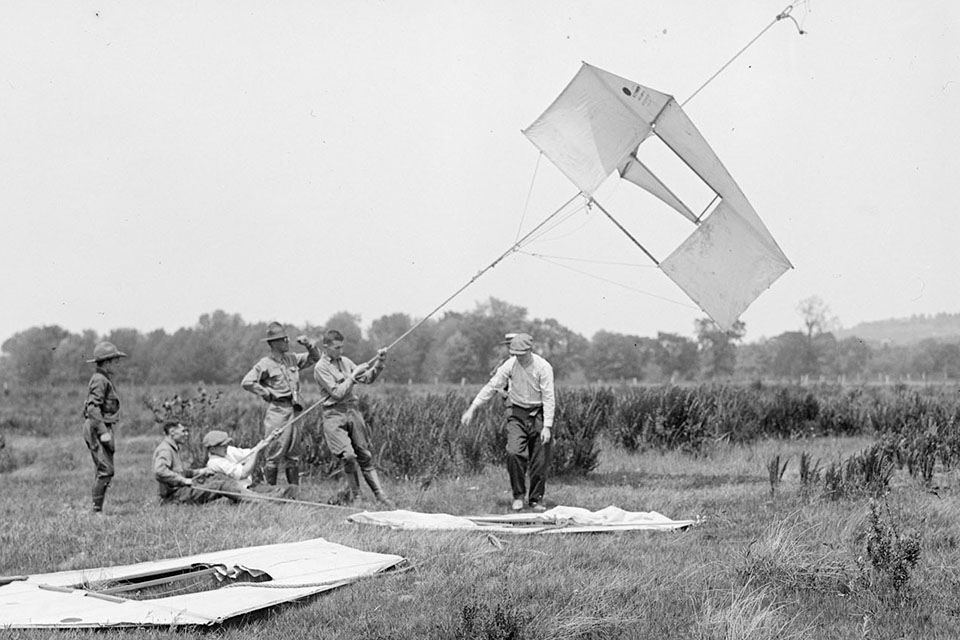

Some 67,000 people turned out expecting to watch the still-new “aeroplane” streak across the sky. But the biggest spectacle that day, according to local newspaper accounts, was seeing Perkins lifted 200 feet off the ground by five huge man-carrying kites. Though the Globe claimed it was the first time an American had ever been carried aloft by a kite, history shows this was not actually the case. Nevertheless, it was by far the highest altitude an American had ever reached in a kite.

Perkins’ fame soon spread. It didn’t hurt that he took as many newspaper reporters up with his Conyne-style box kites as were willing to go. It seems Perkins wasn’t just a capable inventor; he was a savvy publicist too.

The Perkins Man-Carrying Kite was made from a spruce frame covered in silk. After a lead kite 18 to 20 feet in diameter was sent aloft, a train of three to six smaller kites would follow. Once enough lift had been generated, the aeronaut would take a seat in a swing-like contraption, similar to a boatswain’s chair, and be winched into the sky.

Up to 10 men were required to reel Perkins’ kite in or out, depending on wind conditions, with the kite line sometimes extending as much as a mile into the sky. At first Perkins used manila rope as kite “string,” but he eventually switched to metal cable for safety reasons. Subsequent versions of his invention were reportedly capable of lifting up to 2,000 pounds.

Flights, which generally lasted 90 minutes, could obviously only be made when the wind was blowing hard. Perkins reportedly preferred “gale conditions” for his demonstrations. But the biggest challenge was stability. The kites could veer out of control if their line became too vertical, a problem he encountered more than once.

Like many youngsters, Perkins had developed a healthy interest in kites at an early age. But it wasn’t until he apprenticed under Harvard professors A. Lawrence Rotch and H.H. Clayton at the university’s Blue Hills Meteorological Observatory that his interest turned serious. After graduating from MIT, Perkins set his sights on developing his own special breed of kite.

He was not the first to experiment with man-carrying kites. In 1825 British schoolteacher George Pocock used a 30-foot kite to lift his daughter, Martha, 270 feet off the ground. In 1902 American Charles Zimmerman employed a kite to send his wife Ida 10 feet into the sky (which was probably more than enough for her). The first notable man-carrying kite flight in America not involving a family member came in 1907, when U.S. Army Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge was lifted to 150 feet, remaining at that altitude for seven minutes.

For Perkins, 1910 proved to be a watershed year. At a St. Louis aviation meet he set what was then believed to be a world record when his man-carrying kite lifted him to 300 feet. By that time, he was regarded as America’s leading kite expert. As MIT’s class notes stated: “Probably no 1909 man has been so much in the public eye as Sam Perkins. He is a high flyer of the first order.”The Globe, praising his knowledge of upper air currents, also ranked Perkins as “one of the foremost experts in aeronautics in America.”

But not everything went smoothly during all his demonstrations. In November 1910, Perkins had what one newspaper described as a “slight mishap” when the rope connecting his kites snapped, causing him to fall 75 feet. He managed to check his fall along the way, avoiding serious injury, but it was the first of many warnings.

Less than two weeks later Perkins used 12 kites to lift Helene Mallard to 40 feet, presumably to prove that his invention was safe. But the inventor suffered another mishap in Kansas City not long after that. During a demonstration, a cyclone suddenly swept down, collapsing his lead kite. The trailer kites became snagged on a building before disappearing somewhere over Missouri, and Perkins plummeted 150 feet to the ground. The parachute effect of the remaining kites checked his fall, but it was another signal that he was in a dangerous profession.

Perkins was apparently fond of promising newspapers that his kites could “do stunts never seen before.” As a result, he racked up a number of firsts, including setting a 385-foot altitude record, sending a wireless message while aloft and employing his kites for aerial observation, photography, sharp-shooting and even for target practice by airplanes. He paid his bills by selling advertising space on the kites, and he also received a cut of the gate proceeds from aviation meets.

His primary goal, however, was interesting the military in his device. As Perkins announced to the Los Angeles Herald,“Man-carrying kites should prove valuable in war for reconnoitering.” His first opportunity came in January 1911, when he lifted a U.S. Army Signal Corps officer over Los Angeles. Two weeks later he flew members of the 30th Infantry at the Tanforan Air Meet near San Francisco. After Rear Adm. Charles Pond witnessed a demonstration, he asked the inventor if an observer could be sent over water. Ever eager to seize an opportunity, Perkins answered yes.

The next month Lieutenant John Rodgers, who had earlier been designated as one of the U.S. Navy’s first aviators, was strapped to a kite and lofted 400 feet above the deck of the armored cruiser Pennsylvania as it steamed toward San Diego. The Navy would not become a buyer, however. As Perkins later explained, “Since no money was available, use by the Navy was left for future consideration.”

Perkins was invited to demonstrate his invention at King George V’s coronation festivities later that year. Meanwhile, accidents continued to happen. At a Los Angeles event, he was at an altitude of 200 feet when a biplane severed his cable. Although three of his kites were destroyed, he again managed to use the remaining kites to parachute to safety.

World War I brought renewed interest in kites, which would be used by Germany and France for scouting. Consequently, the U.S. Signal Corps ordered another round of tests, though it ultimately led nowhere. One problem was that man-carrying kites were easy targets on the battlefield, which didn’t endear them to their would-be operators. What’s more, improvements in airplanes and kite balloons soon rendered man-carrying kites obsolete, at least for observation purposes.

Still, Perkins kept refining his kites, filing patent applications and undertaking demonstrations of his latest inventions. Though he couldn’t persuade the military to buy any of his man-carriers, his signal kites did meet with some success. When Lieutenant Rodgers attempted the first nonstop flight between San Francisco and Hawaii in 1925, he carried a Perkins signal kite with him (he had opportunity to use it after his flying boat ran out of fuel and landed in the Pacific). When the Army sent five amphibious biplanes on a goodwill tour of Latin America the next year (see story, July 2013 issue), each plane carried a Perkins kite. And Rear Adm. Richard Byrd took three of the kites with him on his first Antarctic expedition, in 1928.

Perkins largely disappears from the historical record after 1930. By the time he died at age 72 near Dorchester, Mass., on October 7, 1956, his many accomplishments had all but been forgotten—likely the reason why the Globe’s obituary mistakenly referred to him as a “balloon expert.” Perkins had indeed spent years flying balloons, but anyone who knew him could have explained that kites were his first love.

Though the U.S. military took a pass on the Man-Carrying Kite, Perkins’ legacy still thrives today. The next time you visit a busy beach resort, you’ll probably see tourists flying in a modern version of his invention: a parasail pulled by a motorboat. It’s a sight that would have made Sam Perkins proud.

Originally published in the September 2013 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.