Last weekend, I met a hero.

Oh, I know, “hero” is a cliché of military history. I’ve always been skeptical of the term. How do you judge a hero? What is the qualification? Do you have to blow up a tank with your bare hands? Hold a lost position all by yourself? Be Audie Murphy?

I’ve thought about this a lot. My dad spent 18 months of his life on the island of Guadalcanal with the Americal Division. He never gave me a lot of details or told a lot of stories, except for that time when he met Eleanor Roosevelt—the moment that let the entire Citino family share in the American dream. But Dad was a medic, and I know enough about World War II to know that he did some pretty heroic things in that time. And he was my hero, anyway.

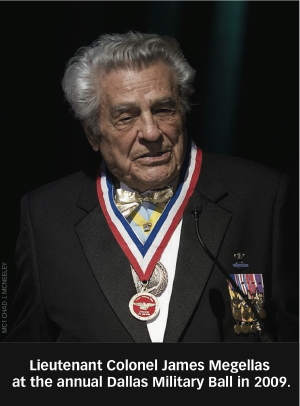

This weekend I met another hero: James Megellas, U.S. Army LTC (retired). Maggie, as his friends call him (and I hope he’ll include me in the list) was a Wisconsin boy, mid-way through his senior year at Ripon College when Pearl Harbor happened. He graduated ROTC in 1942 and accepted a commission as a Second Lieutenant in the army infantry. Originally assigned to the Signal Corps because of his math skills, he wanted to see combat and volunteered to become a paratrooper.

.jpg) And what a paratrooper! By the end of the war, he had fought at Salerno, at Anzio, in Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands, and the campaign into Germany. Along the way, he became the most decorated officer in the 82nd Airborne Division: a Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, two Bronze Stars, two Purple Hearts, Presidential Citation w/cluster, the Belgium Fourragère, six Campaign Stars, and Master Parachutist badge. In 1945, General Jim Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne, selected him to receive the Military Order of Wilhelm Orange Lanyard from the Dutch Minister of War in 1945, the first American so honored by the Government of Holland.

And what a paratrooper! By the end of the war, he had fought at Salerno, at Anzio, in Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands, and the campaign into Germany. Along the way, he became the most decorated officer in the 82nd Airborne Division: a Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, two Bronze Stars, two Purple Hearts, Presidential Citation w/cluster, the Belgium Fourragère, six Campaign Stars, and Master Parachutist badge. In 1945, General Jim Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne, selected him to receive the Military Order of Wilhelm Orange Lanyard from the Dutch Minister of War in 1945, the first American so honored by the Government of Holland.

If there was a defining moment in this heroic career, it came in September 1944. Jim jumped into the Netherlands as part of Operation Market Garden. Ordered to seize the two critical bridges at Nijmegen, Jim’s company had to cross the Waal river in flimsy boats while under murderous machine gun and 20mm antiaircraft fire. If you’re trying to picture this, think four words: A Bridge Too Far. The movie. Robert Redford in front of the boat reciting the “Hail Mary.” The chaplain in the back chanting “Thy will be done.” A bunch of young boys certain they were going to die, but doing what they were told to do, anyway. Maggie was there.

On Saturday, at the University of North Texas, he gave a talk about that horrible day. He’s 95, but in some ways he’s still the same young platoon leader in that boat. You could still see the emotion, the fire. The same determination to do what had to be done. Jim doesn’t romanticize war, or relish it. He told the crowd about friends, young men he had known for years, cut down by random bursts of fire. An officer who said, that morning, “I’m not gonna make it.” They all tried to reassure the poor fellow, but they knew a deeper truth about war: you know when your number’s up. Maybe it’s truths like that one that led Jim to write a book nearly 60 years later, All the Way to Berlin (2003), one of the best books on war I have ever read (and you should read it too). Maybe that’s why, at the age of 89, Jim agreed to travel to Afghanistan and visit his old outfit, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment. The young men there gave him a hero’s welcome, and he’s been back two times since then.

On Saturday, at the University of North Texas, he gave a talk about that horrible day. He’s 95, but in some ways he’s still the same young platoon leader in that boat. You could still see the emotion, the fire. The same determination to do what had to be done. Jim doesn’t romanticize war, or relish it. He told the crowd about friends, young men he had known for years, cut down by random bursts of fire. An officer who said, that morning, “I’m not gonna make it.” They all tried to reassure the poor fellow, but they knew a deeper truth about war: you know when your number’s up. Maybe it’s truths like that one that led Jim to write a book nearly 60 years later, All the Way to Berlin (2003), one of the best books on war I have ever read (and you should read it too). Maybe that’s why, at the age of 89, Jim agreed to travel to Afghanistan and visit his old outfit, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment. The young men there gave him a hero’s welcome, and he’s been back two times since then.

It wasn’t until the very end of the war, Jim told the audience, that he actually realized what it had all been about. What they had been fighting for. The cause for which his friends had died. His battalion liberated a concentration camp. A patrol reported back that they had just come across a German installation of some sort. “A bunch of skinny guys,” the man said. Jim went forward and came across a concentration camp, with inmates in the advanced stages of malnutrition, many close to death (and many who would soon die). In that room in Denton, Texas where Jim was speaking this weekend, you could have heard a pin drop.

I don’t go in much for “greatest generation” rhetoric. But in this case, I will make an exception. Thanks, Jim.

For the latest in military history from World War II‘s sister publications visit HistoryNet.com.