For nearly a decade after the Civil War southwest Texas was a land in torment. Emboldened Indians striking from below the Rio Grande stole tens of thousands of head of livestock, burned out countless ranches and murdered scores of settlers. Many such raiders were from the Kickapoo, a tribe that had migrated to Mexico from the United States.

As late as the 17th century the Kickapoos had made their home south of the Great Lakes, but pressure from competing tribes and westering Anglo-Americans had pushed them steadily southwestward until, by the early 19th century, most lived in the region encompassed by present-day Texas and Oklahoma. In 1839 a small band agreed to move to Mexico, where, in return for land grants and annuities from the Mexican government, they promised to help defend that country’s northern frontier against marauding Comanches and Kiowas. Their alliance with the Mexicans worked so well that over the next quarter century many other bands of Kickapoos joined their tribesmen. In the wake of the Texas Revolution, most settled just across the Rio Grande in the state of Coahuila.

But in December 1862, and again in January 1865, Texas frontier patrols encountered such bands of migrating Kickapoos and attacked them. To the Texans, who had suffered decades of Comanche and Kiowa raids, the presence of large groups of Indians so near their settlements presented a very real threat that required swift and unwavering action. To the Kickapoos, however, the attacks were unwarranted and represented a declaration of war. Once safely settled in Mexico, they swore vengeance against the Texans.

The Kickapoos soon discovered a profitable side to their vendetta, for South Texas, from San Antonio to the Rio Grande, was home to some 90,000 head of horses, mules and cattle with fewer than 4,500 residents to protect them. Thus rustling was ridiculously simple. As Mexican government officials steadfastly refused to allow U.S. troops to pursue raiders into Mexico, the Kickapoos could easily and openly dispose of their plunder in the small-town marketplaces in northern Coahuila. By 1873 they and raiders from other Mexican tribes were responsible for an estimated $48 million in property damage and livestock losses.

Official Washington was inundated with letters and petitions from settlers demanding help and protection. President Ulysses S. Grant and Secretary of State Hamilton Fish grew concerned the Texans might launch retaliatory raids of their own if something wasn’t done. But when Fish tried diplomatic pressure, the Mexican government claimed that local authorities had done all in their power to prevent raiding, that most Kickapoos were peaceful farmers, and that the Mexican settlements had suffered far more from Indian raiders striking from the United States than Texans had from Mexican Indians. The raids continued unabated, as did the outcry.

Finally, in January 1873 President Grant’s patience with the Mexican government was exhausted; the problem, he decided, required a military solution. Grant turned the problem over to Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan, commander of the encompassing Military Division of the Missouri, who immediately ordered the 4th U.S. Cavalry to move from North Texas to Fort Clark in the southern Rio Grande area.

Sheridan’s choice of the 4th was not random. Inspection reports rated it as the finest cavalry regiment in the Army. More important to Sheridan was the knowledge that the 4th was commanded by a young officer of extraordinary talent and ability—Colonel Ranald Slidell Mackenzie.

“I want you to be bold”

Ranald Mackenzie’s career has few equals in American military history. Born on July 27, 1840, into a distinguished family (his father was a noted Navy commander, while one of his uncles was Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who opened Japan to the West), Mackenzie was a frail youth who compensated for his lack of physical stamina with an iron determination and a stern dedication to duty. In June 1862, at age 21, he graduated first in his class from West Point and received an appointment as a second lieutenant in the Army of the Potomac. Over the next 33 months he participated in eight major battles, including Gettysburg, as well as the 1864 Overland campaign and subsequent siege of Petersburg. He rose to the brevet rank of major general, collected seven brevets for gallantry in action and suffered six severe wounds, including the loss of the first two fingers on his right hand, a deformity that earned him the nickname “Bad Hand” among American Indians.

Mackenzie earned repeated praise for his “courage and skill” under fire from such vaunted superiors as Grant, Sheridan, William Tecumseh Sherman and George Meade. He also earned the respect of those who served under him. One such impressed lieutenant deemed him “a greater terror to both officers and men than [Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal] Early’s grape and canister.” Commanding General Grant was so impressed by Mackenzie’s integrity and devotion to duty that he personally requested the young officer be present at Appomattox and afterward take custody of surrendered Confederate property. Grant praised Mackenzie in his memoirs as “the most promising young officer in the Army.”

After the war Mackenzie reverted to his permanent rank of captain in the Army Corps of Engineers. In 1867 he was appointed colonel of the 41st U.S. Infantry, a newly formed black regiment that two years later was reorganized as the 24th U.S. Infantry. In 1871, with the assistance of President Grant, he assumed command of the 4th Cavalry, and in the space of a few months he transformed it from a lackluster outfit into a hardened, disciplined, highly effective frontier fighting force. Operating out of Fort Richardson, in north-central Texas, Mackenzie relentlessly drove himself and his regiment. By the time Sheridan’s orders arrived transferring the unit south, Mackenzie and his men had completed their fourth major campaign against hostile Kiowas and Comanches in just 18 months.

By late March 1873 six companies of the 4th were encamped in and around Fort Clark, near the Rio Grande. That April Secretary of War William W. Belknap and General Sheridan paid a surprise visit to Fort Clark on what was officially termed an “inspection tour.” But behind the facade of a full field review and a grand ball given in their honor, Belknap and Sheridan engaged in two days of secret meetings with Mackenzie. According to later published accounts, Sheridan wasted no time in making his wishes known.

“Mackenzie, you have been ordered down here…because I want something done to stop these conditions of banditry…[and] killing by these people across the river,” the general told the colonel. “I want you to be bold, enterprising…[and] when you begin, let it be a campaign of annihilation, obliteration and complete destruction.”

When Mackenzie asked under whose orders and on what authority he was to act, Sheridan pounded the table and exclaimed: “Damn the orders! Damn the authority! You are to go on your own plan of action, and your authority and backing shall be General Grant and myself.…You must assume the risk. We will assume the final responsibility.”

Sheridan’s inference was unmistakable. Mackenzie was to strike at the raiding Indians’ operational base, which meant crossing into Mexico. In the absence of anything in writing, the responsibility for such an action could very well come to rest wholly on his own shoulders.

For a month Mackenzie made secret preparations for his dangerous assignment. He ordered daily drills for officers and men. Special attention was paid to such field tactics as charging by platoon and dismounted skirmishing, maneuvers that would prove especially useful against Indian villages. In the meantime, Mackenzie’s trustworthy civilian scouts had discovered three large Kickapoo, Lipan and Mescalero villages on the banks of the Rio San Rodrigo, some 40 miles inside Mexico. The scouts spent weeks observing the villages, calculating their strength and mapping the terrain. Finally, on the night of May 16 they reported to Mackenzie that most of the warriors of the Kickapoo village had ridden off to the west that morning. The time to strike was at hand.

By 1 p.m. on May 17 the combined command of 360 enlisted men, 17 officers, 24 Seminole scouts and 14 civilians began to move slowly toward the Rio Grande. Mackenzie planned to arrive at the river at sundown so darkness would shroud the column’s movements. Just before reaching the border, Mackenzie halted his men and in a brief address revealed to them their mission. They listened silently as he explained the ordeals and risks that lay ahead: at least 24 hours of hard riding, a major battle to be fought, the possibility of being hanged or lined up against a wall and shot. He did not tell them he was acting without official written orders or authority, or that, even if successful, the raid might cost him his career. Such were Mackenzie’s burdens; his men had plenty enough to worry about.

Sobered to the realities of their mission, it was a grim and determined column of bluecoat raiders that waded their horses belly-deep in the muddy Rio Grande that evening and splashed up on Mexican soil to ride swiftly and silently westward. For many the next 40 hours would be the most arduous of their lives.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

In the darkness the troopers blindly followed their scouts on a winding, tortuous route through dense canebrakes, fields of cactus and chaparral, down rocky ravines and over open dusty ground. In the distance they could see the lights of small and isolated ranch houses, but the scouts had chosen routes that detoured far around these places. It was vital to the success of the mission that the countryside be aroused as little as possible to the Americans’ presence.

Throughout the night they rode. Mackenzie wanted to be in position to attack at daybreak, and he pushed the troopers unmercifully. The heavily loaded pack mules began to fall behind, so Mackenzie impatiently ordered the packs cut loose and abandoned. Onward the command rode, short on supplies and rations, racing against the dawn. “Sleep almost overpowered us, and yet on, on we went,” one officer recalled. “Nothing was heard save the ceaseless pounding of the horses and the jingle of the saddle equipment.”

Surprise Attack

Shortly before sunup, having ridden 63 hard miles since crossing the Rio Grande (23 more than the straight-line distance), the raiders reached the San Rodrigo just upstream of the Indian villages. Mackenzie called a halt so the men and animals could refresh themselves in the cool water and prepare for the attack. Saddles were re-cinched and girths tightened, carbines were checked and loaded, and sabers were strapped on and adjusted.

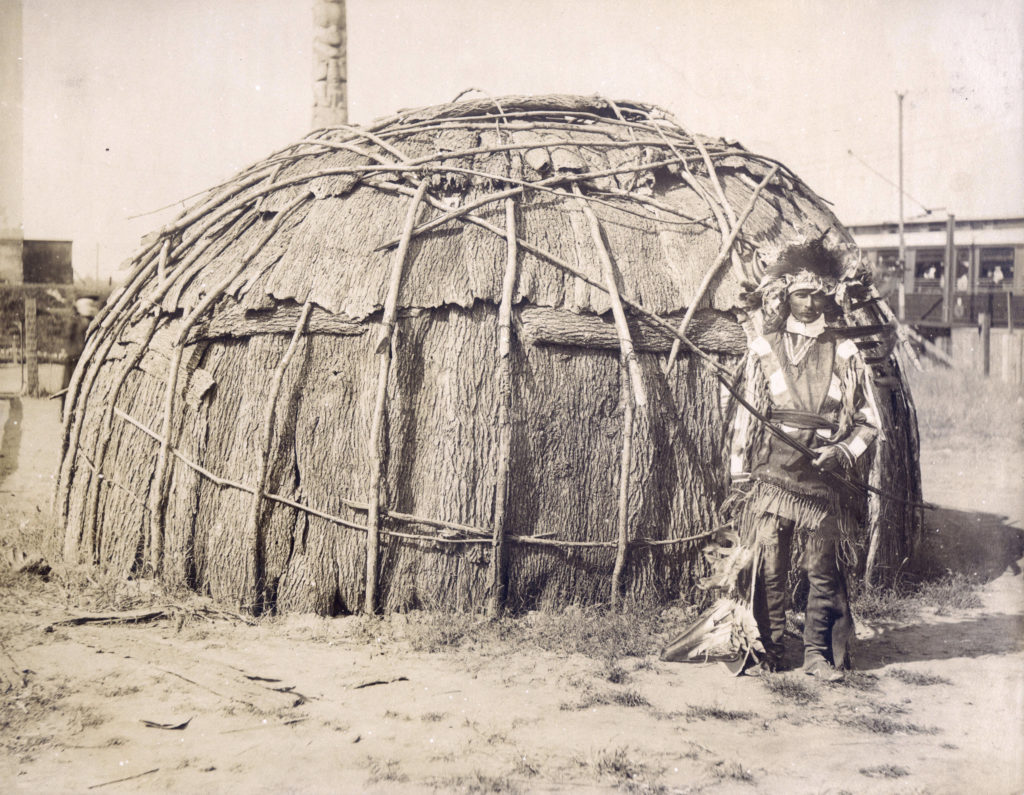

Just as dawn was breaking, Mackenzie led his men down the riverbed, using its high banks for cover. Abruptly, the instructions “prepare to charge” were passed down the column. The troopers wheeled and spurred their mounts up the bank into full view of their objective. Below them ran about a mile of gently sloping ground, and at its base the Americans could see huts and wickiups stretched along the winding San Rodrigo. The Kickapoo village was the nearest and largest, while that of the Lipan lay a quarter mile or so beyond, with the Mescalero encampment beyond that. To any early risers in the Indian camps, it must have seemed as if the soldiers had suddenly risen from the earth.

Orders flew up and down the line, and the soldiers deployed into platoons. The gray horses of I Troop, the leading unit, lengthened their gait from a trot into a canter. Then, some 150 yards from the village, the command, “Charge!” rang out, and I Troop broke into a full gallop. “And then,” recalled Mackenzie’s adjutant, 2nd Lt. Robert Carter, “there burst forth such a cheering and yelling from our gallant little column as that Kickapoo village never heard before. It was caught up from troop to troop and struck such dismay to the Indians’ hearts that they were seen flying in every direction.…I never saw such a magnificent charge as that made by those six troops of the 4th U.S. Cavalry on the morning of May 18, 1873.”

The Kickapoos were taken completely by surprise. Many of their warriors had left the day before, and those who remained stood no chance. As the men of I Troop slashed through the outer perimeter of their village, the Indians fled in all directions, across cornfields and irrigation ditches, through swampy bogs and out among the stands of cactus and bayonet grass, with the soldiers in close pursuit.

The rest of Mackenzie’s command charged through the village by platoons, volley firing as they went, then wheeling out of the way to reload and prepare to charge again. The rear elements dismounted and began to set fire to the canvas tepees and grass huts. The initial panic of the surprise attack overcome, the surviving Kickapoos—men, women and children alike—fought back like demons. For those involved, the sights and sounds of battle blended. The chaos of forms rushing in all directions through the smoke and dust merged with the crack of carbines and pistols, the screams of women and children, and the shouts of soldiers and warriors to create an awful and unforgettable spectacle.

But in a matter of minutes it was over, and the troopers moved on to the other villages. The Lipan and Mescalero bands had taken flight at the first sound of shots, and the soldiers moved unopposed among their deserted dwellings, setting them afire. Soon all three villages had been razed to smoking embers.

The exact number of Indians killed is not known. Mackenzie counted 19 bodies, but many more must have remained undiscovered in the ditches, beneath the riverbanks and in other hidden places. Forty women and children were taken prisoner, as was Costilietos, principal chief of the Lipans, who was literally roped in by one of the Seminole scouts as he tried to flee through the brush. The soldiers also captured 65 ponies. These were parceled out as a reward to the civilian scouts who had surveilled the villages. Mackenzie’s losses were remarkably light. One soldier was killed in the charge, and two were wounded, one so severely the surgeon had to amputate his arm on the spot.

A Long “Night of Horror”

By 1 p.m. the preparations for the long march home were completed. Travois had been crafted to carry the wounded, and the Indian prisoners had been assigned captured ponies to ride. After a last sweep to assure the complete destruction of all Indian property and stores, Mackenzie and his men started for the Rio Grande.

They soon rode through the nearby town of Remolino, whose villagers met the Americans with sullen scowls and curses muttered in Spanish. Beyond town the scouts wisely chose a more direct route to the border than the one used to reach the Indian villages. Mackenzie’s overriding concern was to get his men across the Rio Grande before the Mexican populace rose against them.

But the men and horses were too exhausted to move with much speed. The constant fear of ambush by overwhelming numbers of Indians or Mexican soldiers combined with fatigue, searing heat and choking dust to make the return trek an agonizing experience. The miles and hours crawled by. Nightfall brought relief from the heat, but for many in the command it marked their third straight night in the saddle, and the need for sleep became almost overpowering. Officers and sergeants used any means at their disposal to keep the men awake and moving. The scouts reported groups of riders on their flanks, but no attacks came. One officer later called it a “long, interminable night of horror, of nightmare.”

Finally, the gray light of dawn revealed in the distance the welcome sight of the Rio Grande. The bone-tired men and horses waded into its refreshing waters, and soon the entire column stood once again on U.S. soil. The troopers made camp, and shortly thereafter a supply train loaded with rations and forage arrived. The command spent the rest of the morning sleeping and feasting. The return to Texas had come none too soon, for that afternoon a large body of Indians and Mexicans appeared on the south side of the river. They hurled challenges and abuse at the troopers and several times appeared ready to attack. But Mackenzie ordered his best marksmen to take positions covering the ford, and by sundown the would-be avengers had withdrawn. After a night of badly needed rest the command marched to Fort Clark at a leisurely pace.

Favorable Response

Mackenzie’s raid into Mexico was one of the most demanding and daring missions ever undertaken by the post–Civil War U.S. Cavalry. Mackenzie and his men rode more than 140 miles in 38 hours, violated Mexican sovereignty, attacked allies of the Mexican government, destroyed three large villages and captured 40 prisoners—all without official orders or authority.

The response to the action was immediate and favorable. Sheridan enthusiastically supported Mackenzie, saying, “There cannot be any valid boundary when we pursue Indians who murder our people and carry away our property.” The San Antonio Daily Express was effusive in its praise. “If western Texas had the sole command in electing the next president, [Brevet] General Mackenzie would be the man,” it wrote. “Three cheers for General Mackenzie’s pluck and energy—three cheers for his brave boys!” On June 2 the Texas Legislature passed a joint resolution extending “the grateful thanks of the people of our state and particularly the citizens of our frontier…to General Mackenzie and the troops under his command for their prompt action and gallant conduct in inflicting well-merited punishment upon these scourges of our frontier.” A week later the War Department officially commended Mackenzie for his action.

The fact Mackenzie had attacked villages that did not have their full complement of defenders didn’t seem to faze either American citizens or the government in the least. As many Texans pointed out, such were the very same tactics Indian raiders had employed for decades against isolated farms and ranches on the frontier, so Mackenzie’s actions were wholly justified. Years of cruelty and brutality by both sides had combined to make chivalry on the frontier, if it ever existed, an outdated concept.

Understandably, the Mexican government was less than happy about the raid, but it chose not to turn it into an international issue. Notes were exchanged between the Mexican minister and Secretary of State Fish, and with that mild protest, the matter was dropped.

As for the border situation, Indian raids all but stopped. Mackenzie’s attack had shattered the complacent belief of Mexican tribes in the protection offered by the Rio Grande. Fearing similar strikes, many bands split up and moved into the mountains. The Kickapoos, in exchange for the release of their captive wives and children, agreed to return to the United States. By 1874 more than half the tribe had resettled at Fort Sill in Indian Territory.

Mackenzie’s bold expedition did not prove the final answer to the problem of Indian depredations in southwest Texas, but it did succeed in bringing peace and order to the area for a span of years. It also provided one of the most thrilling exploits in the annals of Indian warfare and made Colonel Ranald Mackenzie and his raiders living legends on the frontier.

For further reading on the topic author Allen Lee Hamilton recommends On the Border With Mackenzie, by Robert G. Carter; The Kickapoos: Lords of the Middle Border, by Arrell M. Gibson; and Bad Hand: A Biography of Ranald S. Mackenzie, by Charles M. Robinson III.