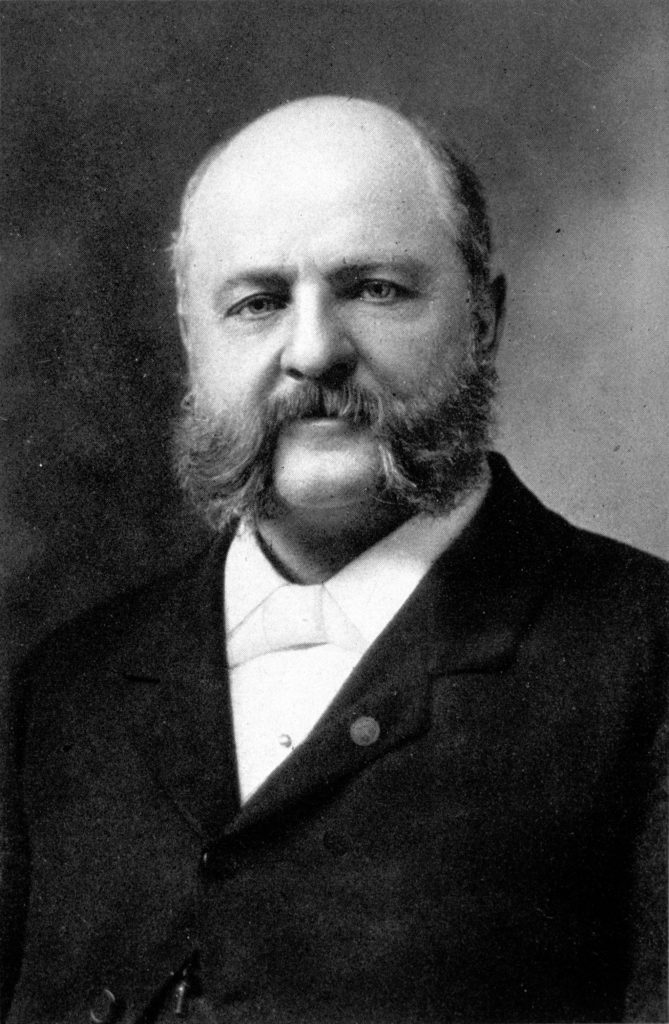

Anthony Comstock always dressed in black and white: black suit and shoes, starched white shirt, black bow tie—except at Christmas, when he replaced the black tie with a white one. Comstock saw the world in black and white, good and evil. You worked for God or you slaved for Satan. Comstock toiled for God, fighting what he saw as Beelzebub’s most insidious creation—erotica. There was, he proclaimed, “no more active agent employed by Satan in civilized communities to ruin the human family than EVIL READING.”

For 42 years, Comstock served as the United States government’s official hunter of racy novels, risqué postcards, and sex manuals that dared to explain contraception.

Brawny, broad-shouldered, and zealous, he loved to kick in doors and vault through windows to arrest smut merchants—especially if, as often was the case, he’d brought along a gaggle of reporters. Comstock craved publicity and meticulously recorded his triumphs. “In the 41 years I have been here, I have convicted persons enough to fill a passenger train of 61 coaches—60 coaches containing 60 passengers each and the 61st almost full,” he bragged not long before his death in 1915. “I have destroyed 160 tons of obscene literature.”

A Puritan born on a Connecticut farm in 1844, Comstock grew up in a teetotaling Congregational household whose members spent most waking hours working or praying. One night a teenaged Anthony got drunk with a friend. Waking with a hangover that felt like God’s punishment, he swore off booze for life. At 18, he discovered that a store was illegally selling grog, so he broke into the place by night and opened the taps, emptying every keg—his first attack on God’s enemies.

In 1863, he joined the Union army, which shipped him to the Florida coast. He saw little combat against Confederates but fought the devil every day. When his unit received its whiskey ration, he poured his share on the ground. His irked comrades would have been happy to drink it, but Comstock refused to be a party to the consumption of firewater. Sins of the flesh likewise tormented him.

“I debased myself,” Comstock wrote in his diary of his habitual masturbation. “I deplore my sinful weak nature…”

After the war, he became a clerk in a Manhattan dry goods business and married a pious woman ten years his senior. When a daughter died in infancy, the couple adopted a baby girl.

But dry goods and domestic life bored Anthony. Lusting for action but loathing lust, he launched a personal crusade. He would buy racy books, then convince city cops to deputize him to arrest the sellers. One day, eager for publicity about his exploits, he brought a New York Tribune reporter with him as he busted seven booksellers.

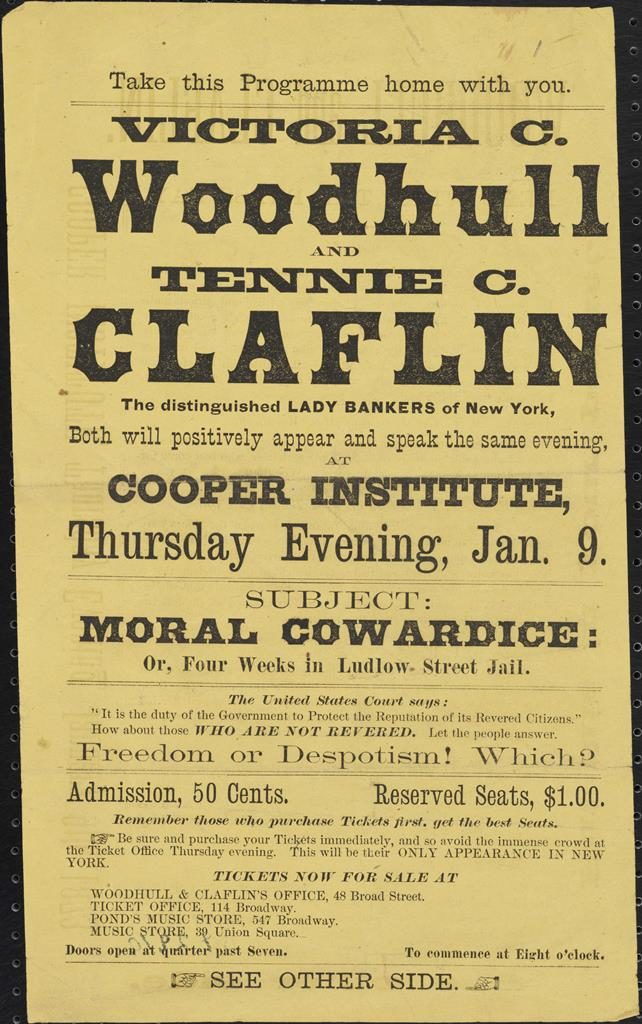

In 1872, Comstock went after New York’s famous stockbroker sisters—Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin—who published a weekly newspaper that advocated women’s suffrage and free love.

When the scandal-mongering siblings published an article accusing America’s most famous minister, Henry Ward Beecher, of adultery, Comstock got the sisters charged with obscenity. The indictment made him famous, but after months of legal wrangling, the charges were dismissed. Bans on obscenity did not include newspapers.

Obviously, Comstock needed a stronger law, so he traveled to Washington, DC, to lobby for one. Lugging a carpetbag of dirty books, he buttonholed congressmen, citing saucy passages, and won their votes for “An Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use”—soon shortened to “the Comstock Act.” Signed by President Grant in 1873, the act outlawed use of the mails to send “obscene, lewd or lascivious” materials—as well as sale or possession of devices used “for the prevention of conception.”

Congress appointed Comstock a “special agent” of the U.S. Post Office, deputized to sniff out and snuff out porn and prophylactics. He got a badge and power to make arrests but no salary, so a like-minded organization, the Society for the Suppression of Vice, hired him as its staff vicebuster. He worked full time and loved the job. In 1873 alone, he logged 23,000 miles—his stops included Boston, Chicago, St. Louis, and St. Paul—arresting 55 individuals and seizing 67 tons of one-handed books, 194,000 pictures, 5,500 decks of naughty cards, and 60,300 contraceptive devices.

A tireless scold, Comstock maintained his frantic pace for 40 years, all the while hectoring Americans that “EVIL READING” inspired lust, which “defiles the body, debauches the imagination, corrupts the mind, deadens the will, destroys the memory, sears the conscience, hardens the heart and damns the soul.” By the late 1870s, he had defeated the nation’s major publishers of hot stuff, but rather than declare victory the zealot became overzealous, attacking political dissidents, birth control advocates, and, famously, playwright George Bernard Shaw.

In 1878, Comstock arrested Ezra Heywood. The charge brought against the eccentric pacifist and atheist? Publishing Cupid’s Yokes, a 23-page endorsement of free love. The pamphlet was about as erotic as a telephone directory, but Heywood had irked Comstock by denouncing him in it as “a religio-monomaniac.” Convicted under the Comstock Act, Heywood drew two years at hard labor, but President Rutherford Hayes pardoned him after six months. In 1882, Comstock arrested Heywood once again, for selling Cupid’s Yokes and publishing Walt Whitman’s poem “To a Common Prostitute.”

In 1887, Comstock raided a Fifth Avenue gallery, seizing 117 photographs of paintings by French artists depicting unclothed models. “Let the nude be kept in its proper place,” the Savonarola of Sensuality said, “out of the reach of the rabble.” In 1893, Comstock demanded that Chicago lock up World’s Fair belly dancers on charges that they were perpetrating an “assault on the sacred dignity of womanhood.”

In 1905, Comstock warned the NYPD that a Broadway theater was rehearsing Shaw’s play Mrs. Warren’s Profession. Though Comstock hadn’t seen the play or read the script, he’d heard the titular “profession” was prostitution. He denounced Shaw as “an Irish smut dealer” and promised to “investigate his books.”

The playwright responded appropriately. “Comstockery is the world’s standing joke at the expense of the United States,” Shaw said. “Europe likes to hear of such things. It confirms the deep-seated conviction of the Old World that America is a provincial place.”

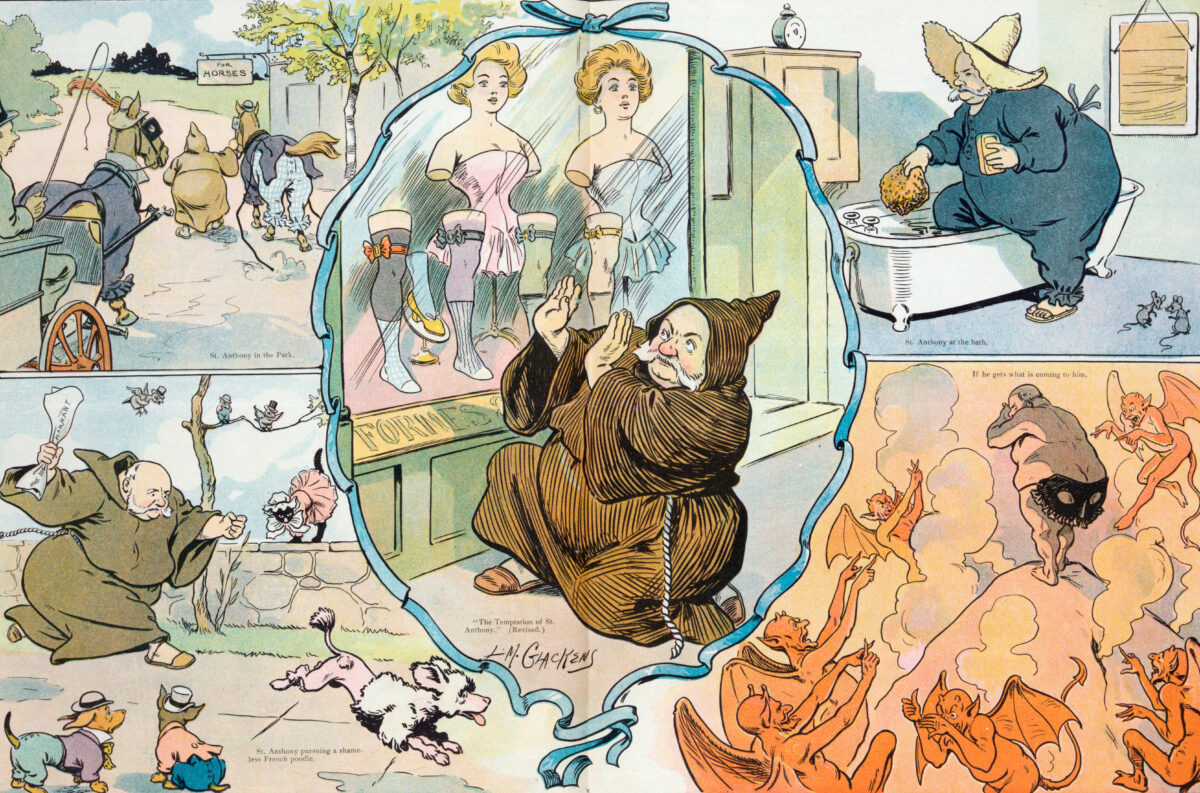

By then, Comstock, to his vast irritation, had become a laughingstock for many Americans. Newspaper columnists mocked him as a yammering fuddy-duddy. Cartoonists parodied his muttonchop whiskers. Increasingly irascible as he aged, he was ejected from multiple courtrooms for yelling at prosecutors who refused to prosecute those he’d arrested.

In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson named Comstock to represent the United States at the International Purity Conference, taking place that year in San Francisco.

Comstock delivered several speeches at the conference, then caught a cold, which became pneumonia and killed him. Federal authorities enforced the Comstock Act until 1965. Its namesake took one secret to his grave: If erotica “corrupts the mind,” how was Anthony Comstock to spend four decades wallowing in titillation and yet remain uncorrupted?