By the summer of 1944, as the U.S. Army Air Forces’ massive daylight bombing campaign decimated the Third Reich’s war industry, the Luftwaffe was but a shadow of its former self.

Despite the impressive combat record of Germany’s Me-109 and Fw-190 fighters, the loss of experienced pilots, fuel shortages, reduced training time and the destruction of factories had greatly reduced the Luftwaffe’s effectiveness. At the same time, burgeoning Allied resources allowed the U.S. and Britain to fill the skies with warplanes that soon flew largely unchallenged over the enemy homeland.

In desperation, the crumbling Third Reich sought a technological edge through the development and deployment of “wonder weapons” such as the sleek Me-262 Schwalbe (Swallow), the first German production jet fighter. The Me-262 hadn’t initially been considered for mass production after its first flight with jet engines in July 1942, but General der Jagdflieger Lt. Gen. Adolf Galland wanted it to be given top priority as an air superiority fighter.

Several factors made that impractical. Despite its impressive speed, the Me-262 required highly advanced materials that were in short supply and thousands of man-hours to build. Its twin Junkers Jumo 004 engines had a very short service life, requiring frequent overhauls. Slow acceleration and limited range were also problems for the new jet.

Given these difficulties, late in the war armaments minister Albert Speer proposed building a huge fleet of simple, agile and fast single-engine jet fighters using steel and wood rather than advanced alloys and aluminum. The German Ministry of Aviation (Reichsluftfahrtministerium, or RLM) sent out a request for proposals to several top firms on September 8, 1944, including Messerschmitt, Junkers, Blohm & Voss and Heinkel. Not surprisingly, Messerschmitt passed on the project right away, favoring the Me-262. Junkers also bowed out. Blohm & Voss submitted a design for the P.211, featuring a jet engine buried in the fuselage with a nose air intake. But the time required to build each aircraft was too long for the hard-pressed Luftwaffe.

Ernst Heinkel was well ahead of the competition. His special projects branch director Siegfried Günter had already envisioned a simple, single-engine jet fighter, designated the P.1073. In a paper presented on July 10, 1944, he wrote that “air superiority is dependent not only upon the number of single-seaters but also upon the speed of the single-seat fighter. Should enemy jet fighters be deployed, the Me-262 could not be counted on for air superiority, because its unswept wings and the placement of its engine nacelles give too much resistance—at low altitudes, its fuel expenditure is quite large and its range quite small. For these reasons, it is necessary to concentrate on a single-seat aircraft with the least possible amount of equipment and not limit fuel to so small a portion of the overall weight.”

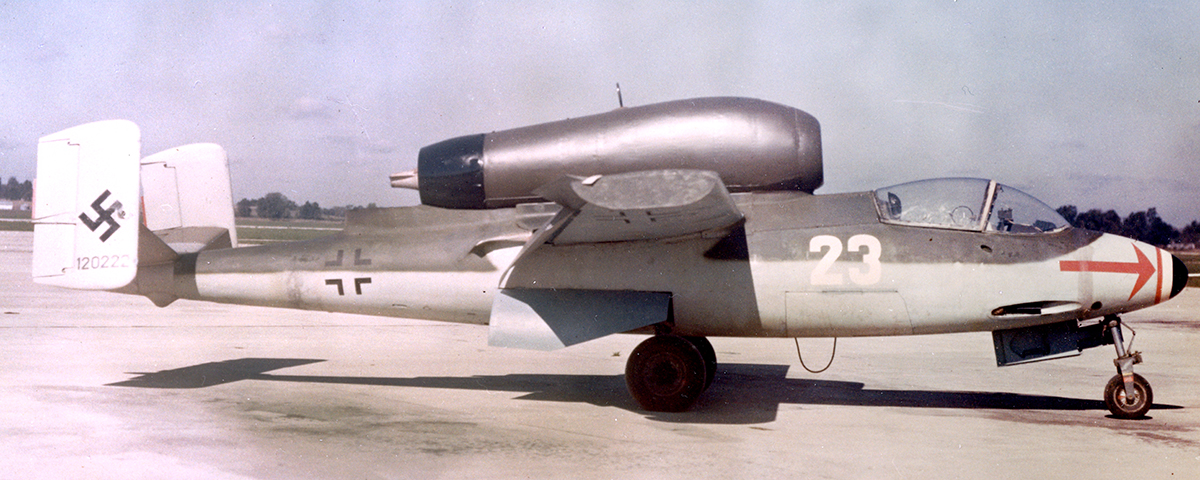

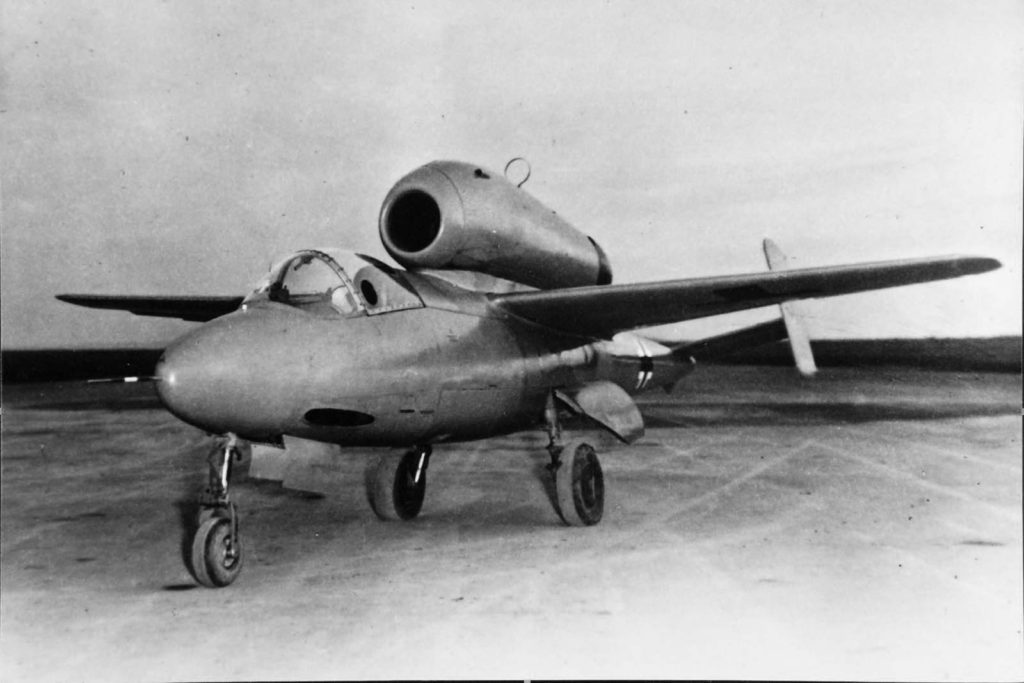

The P.1073 had a tubular frame fuselage and wings, twin rudders and retractable landing gear. Its reliable BMW 003 axial-flow turbojet was dorsally mounted, with the exhaust nozzle vented above the stabilizers.

Günter’s team redesigned the 1073 to fit the RLM’s needs. Heinkel’s lead prompted the RLM to award that firm the contract on October 19. The airplane was officially named the Volksjäger (“People’s Fighter”), and designated the He-162. Postwar examination of RLM documents would reveal that the number 162 had been used to deceive Allied intelligence into thinking the plane had been under development for some time and was a proven quantity.

Heinkel’s Rostock Flugzeugwerke team went to work, and in the remarkably short span of 74 days the prototype He-162 V-1 rolled out of the factory. It weighed just over 6,180 pounds fully loaded, with a third of its weight consisting of wood. Heinkel test pilot Gotthard Peter made the maiden flight on December 6, reaching nearly 500 mph—only 50 mph slower than the Me-262. The BMW 003’s 1,700-pound thrust gave the He-162 a far better power-to-weight ratio than that of the Messerschmitt. But while Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring wanted the jet to be flown by Hitler Youth in defense of the Fatherland, it was immediately obvious that would never work. Though the He-162 was very nimble, only experienced pilots could safely fly it.

Four days later, while demonstrating the aircraft for RLM and Luftwaffe officials, Peter was making a high-speed pass when catastrophe struck. The aileron on the port wing tore off, taking part of the wing with it. Peter was killed in the crash. Investigation showed the glue used in wing construction was inadequate under high-speed aerodynamic stresses.

The BMW turbojet, which required frequent maintenance, was fitted into a streamlined pod just behind the bubble canopy. While this had several advantages, it was a concern to the pilots, since it would be nearly impossible to bail out without being forced against the gaping jet intake. The design therefore incorporated an ejection seat, fired by an explosive cartridge triggered by the pilot on the right armrest.

Production of the He-162 began while the second prototype was still being tested, with speeds limited to 310 mph. Some of the teething problems could only be alleviated via hastily conceived modifications. The He-162’s pitch instability, for example, resulted in the addition of lead ballast in the nose,“drooping wingtips” and strengthened wings. The third and fourth prototypes were tested in midJanuary 1945, even as the production line was up and running—an indication of the pressure the Luftwaffe was under to get the Volksjäger into frontline service.

The original specifications called for twin MK 108 30mm cannons mounted in the nose, each loaded with 50 rounds of ammunition, resulting in the grandly named Kampfzerstörer, or Bomber Destroyer. When the heavy recoil from that armament proved to be too much for the diminutive fighter’s frame, the He-162A-2 was armed with twin MG 151 20mm cannons, each with 120 rounds.

The first jet off the regular production line was an He-162A-1 on January 28, 1945. By early February, Heinkel reported it had 71 fuselages finished and 58 more on the assembly line, well below what the RLM had demanded. The delay was due to the decentralization of the German aircraft industry driven by the Allies’ strategic bombing campaign. While some of the work was done at the Heinkel factory and Junkers’ Bernberg plant, Speer decided that final assembly would be performed by forced labor at underground sites such as the Nordhausen Mittelwerke facility in the Harz Mountains.

The RLM organized a special testing unit, Erprobungskommando 162, to evaluate the Volksjäger at Rechlin, near Berlin. Lieutenant Colonel Heinz Bär, a 221-victory ace, took delivery of several He-162s in February. While tests revealed serious stability problems, one pilot reported that the Volksjäger was “a firstclass combat aircraft.” After overseeing a hurried evaluation of the new jet, Bär was transferred to Jagdverband 44 to fly Me-262s.

In mid-February, Jagdgeschwader 1 (JG.1) was reorganized as the first operational Volksjäger unit. Its pilots all had previous experience in Fw-190s or Me-109s. Command of JG.1 was given to Colonel Herbert Ihlefeld, a veteran with 123 victories. Two groups of 50 aircraft each, designated I/JG.1 and II/JG.1, were assembled at Rechlin. JG.1 took delivery of its first He-162s at the Heinkel airfield at Marienehe. Instructed by Heinkel pilots, the fighter wing’s members learned how to fly the new jet. After just 20 minutes at the controls, they were deemed ready for combat.

Meanwhile production of the Volksjäger proceeded rapidly, with nearly 200 completed by the end of March 1945. The Luftwaffe had set an impossible goal: 1,000 He-162s built per month by the end of June.

What was it like to fly Germany’s wooden jet? Harald Bauer, who served as a Heinkel factory pilot, provided some insights during a recent interview.

After being wounded while serving as an anti-aircraft gunner, Bauer was assigned to a Luftwaffe training unit.“It was in Stendal and Rechlin, north of Berlin,” he recalled. “We went from the Arado 96 to the Focke-Wulf 190. We were each paired with an experienced fighter pilot, who showed us how to fight the Allied bombers. We weren’t supposed to take on the fighters. The base was under constant threat of air attack, and sometimes we didn’t have fuel to fly more than a short hop. After landing, we pushed the planes back into the woods and put netting on them.” Bauer’s time in the Fw-190 was cut short due to a landing mishap. “I stepped on the brakes too hard on a landing and put it on the nose,” he said.

In early March the Luftwaffe decided experienced pilots were needed for its new jet fighters, and time should not be wasted training new pilots. “In March 65 of us were attached to the Heinkel works in Rostock and Marienehe,”Bauer recalled.“We were Werkespiloten, factory pilots.” Their first job was to make sure the new jets were safe for combat airmen. “We were at the very bottom of the Luftwaffe’s stable of pilots. The Luftwaffe wanted to make sure there was no sabotage, so we were told to put each plane through a 20-minute test of climbing, diving and so on. Then the Luftwaffe inspector put an ‘Accepted’ stamp on the aileron.”

Bauer and his comrades then delivered the He-162s to the JG.1 bases.“We were told to fly at a certain altitude, at a certain speed and just get it there. After delivering a plane, we were to hitch a ride on a transport or a truck or take a train back to the Heinkel works. I think I personally ferried about 10 or 15.”

Bauer’s last flight in a Volksjäger began on March 23. “I took one north to deliver to the base at Parchim, north-northwest of Berlin,” he remembered. “The Allies were bombing the base, and the Reichsjägerwelle, the fighter communications radio, told me to go to Varel and wait until morning. The next morning, the 24th, I was told to take off and get clear. American bombers were coming. I climbed into the plane and got off the ground. I didn’t even think of trying to fight. There was no ammunition in the cannon.”

Twenty-five B-17Gs of the 490th Bomb Group were approaching Varel that day. In the nose of the lead Fortress was navigator Lieutenant Bob Durkee, who spotted several planes taking off and called on escorting P-51 Mustangs to “Get those bogies down there.”

Bauer did his best to evade, but suddenly he saw “red tracers coming down on both sides of the cockpit. Then one hit the engine, came through the canopy and buried itself in my leg. The ejection mechanisms weren’t installed until after we delivered the planes, so I had to either bail out or crash-land. I’d heard horror stories of pilots being banged against that huge BMW engine intake, and didn’t want to try it. One of the Heinkel mechanics had told me that if we just turned the plane over, we could jump out safely. But the engine intake was still right there, waiting.”

He brought the crippled fighter down in a meadow. “The He-162 did not glide well; it fell like a rock. But I got it down. And when I realized I was OK and was trying to get out, I heard an American voice saying, ‘That son-of-a-bitch is still alive.’ ” Bauer had bellied into a field behind American lines. The U.S. 2nd Armored Division had crossed the Rhine River the night before, and the pilot looked up to see tanks and troops approaching.

He was taken to a hospital, where the doctor pulled a .50-caliber bullet out of his leg. “He told me it had probably been spent by passing through the engine and canopy,” Bauer recalled, adding, “He let me keep it.”

Of the 65 factory pilots assigned to fly He-162s to JG.1, there were only about five left at war’s end. “None of them were lost to combat,” said Bauer. “They died or crashed during ferry flights or learning to fly them.”

On April 7, 134 B-17s bombed Rechlin, forcing I/JG.1 to move to another base at Leck in Schleswig-Holstein, close to Denmark. In mid-April the I/JG.1 pilots began combat operations. Though they had had little time to become skilled with their new mount, they were pitted against the Allies’ best planes and pilots. The He-162 did offer at least one advantage: Its simple construction and design allowed for quick repair and replacement of the engine and other vital components. Where battle damage would have grounded most other German planes for days or weeks due to a lack of replacement parts, JG.1 could discard a damaged Volksjäger in favor of a new aircraft just off the assembly line.

I/JG.1’s mission was to attack low-flying Allied fighters. On April 19, a captured RAF fighter-bomber pilot claimed during interrogation that he had been shot down by a jet aircraft. His description matched the He-162. Colonel Ihlefeld, JG.1’s commander, attributed the victory to Cadet Günther Kirschner, but the cadet was unable to put in for the credit, as moments later he was shot down and killed by a Hawker Tempest.

First blood was officially drawn on April 26, when a Staff Sgt. Rechenbach shot down a de Havilland Mosquito, confirmed by two other pilots. The sergeant was killed the same day. On May 4, 2nd Lt. Rudolf Schmitt claimed a Hawker Typhoon (in fact a Tempest), but a German flak unit put in a counterclaim and was credited with the victory.

The war in Europe was ending at that point. JG.1’s pilots continued to fly right up to May 5, when British forces occupied Leck. In all, JG.1 lost 13 planes and 10 pilots, mostly due to accidents rather than combat losses.

If fighting had continued for a few months longer and Heinkel had continued producing He-162s, Allied fliers would have seen something terrifying in the skies over Germany: hoards of sleek, nimble jet fighters capable of running rings around the bomber formations. After the war, British, American and French air forces captured the remaining He-162s and flew some of them. Legendary British test pilot Captain Eric “Winkle” Brown judged the jet “an innovative concept that was quite tricky to operate.” He called it “an unforgiving aeroplane,” but noted that it was an effective gun platform, and “as a backup for the formidable Me 262 it could conceivably have helped the Luftwaffe to regain air superiority over Germany had it appeared on the scene sooner.”

Former Volksjäger pilot Harald Bauer ended up in the United States following the war, where he resumed his aviation career. Since his mother was American-born, he was eligible to join the U.S. armed forces. In March 1952 Bauer joined the U.S. Navy. At the height of the Cold War, he flew Lockheed EC-121 Super Constellation radar aircraft attached to an early-warning squadron at Elmendorf, Alaska. “Our job was to test the Soviet air force’s response time when they detected U.S. aircraft,” he said. After that tour, Bauer was told that he would have to qualify for carrier operations if he wanted to remain in the Navy. “I said auf Wiedersehen,” he said, laughing. “I don’t land on postage stamps in the middle of the ocean.” He went on to work for the Associated Press, United Press International and United International Pictures. Today he’s a member of the Estrella Warbirds Museum in Paso Robles, Calif.

Several He-162s are now on static display in museums around the world, including a fully restored Volksjäger at the Planes of Fame Air Museum, in Chino, Calif.

Mark Carlson’s book Flying on Film: A Century of Aviation in the Movies 1912-2012 was recently published by BearManor Media. Further reading: Heinkel He 162: From Drawing Board to Destruction, by Robert Forsyth; Heinkel He 162, by David Myhra; Heinkel He 162 “Volksjäger,” by Heinz J. Nowarra; and Wings of the Luftwaffe, by Captain Eric “Winkle” Brown.

Originally published in the July 2013 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.