Italian aviator Francesco de Pinedo earned accolades for his marathon flights, but his desire to break records ultimately proved a fatal attraction.

On November 7, 1925, a single-engine flying boat touched down on Rome’s historic Tiber River to tumultuous acclaim. At the controls were pilot Francesco de Pinedo and mechanic/copilot Ernesto Campanelli. In 370 flying hours they had just completed an incredible 35,000-mile, three-phase aerial odyssey halfway across the world, from Italy to Australia, Japan and back.

Born into an aristocratic Neapolitan family in 1890, the Marquis Francesco de Pinedo was a naval academy graduate who saw action in destroyers during the 1911-12 Italo-Turkish War, which witnessed the first use of airplanes in combat, by the Italians. In 1917, after pilot training, de Pinedo joined the naval air division and spent the remainder of World War I flying reconnaissance missions.

In 1924 he transferred into Italy’s newly independent air force, the Regia Aeronautica. Destined for staff work, the reserved young major soon requested a leave of absence to embark on the first of a number of flights intended to demonstrate the superior long-distance potential of seaplanes over their land-based counterparts.

De Pinedo elected to fly to Australia and the Far East in a virtually stock SIAI S.16ter, an open-cockpit biplane flying boat. Powered by a Lorraine-Dietrich 450-hp engine, it could fly for up to nine hours and had a range of more than 900 miles. He named the rugged little seaplane Gennariello after the patron saint of Naples, St. Gennario.

Setting off from Lake Maggiore on April 20, 1925, de Pinedo and Campanelli flew eastward across the Mediterranean to North Africa before crossing the featureless Syrian Desert to alight on the Tigris River at Baghdad. There the resourceful Campanelli reportedly used a copper frying pan from a local kitchen to improvise a metal patch for a leaking oil tank.

Continuing along the Persian Gulf, they arrived in at Karachi on May 5. After crossing India and the turbulent Bay of Bengal, on May 14 they reached Rangoon, Burma, where the flying boat’s hull was scraped and repainted. They made it to Singapore 10 days later and arrived at Broome in northern Australia on May 31.

After 10 weeks spent touring Australia, the Italians headed northward from Cooktown on August 13, island-hopping by stages to New Guinea, Manila and Shanghai, reaching Tokyo on September 26. After an engine change in Japan, on October 17 they headed back to Italy via Hong Kong and Rangoon.

In Rome de Pinedo was lauded by Prime Minister Benito Mussolini and promoted to lieutenant colonel. The trusty Gennariello was not only the first seaplane to fly from Europe to Australia, it was the first airplane to do so and return—a magnificent achievement for the two airmen and the international prestige of Italian aviation.

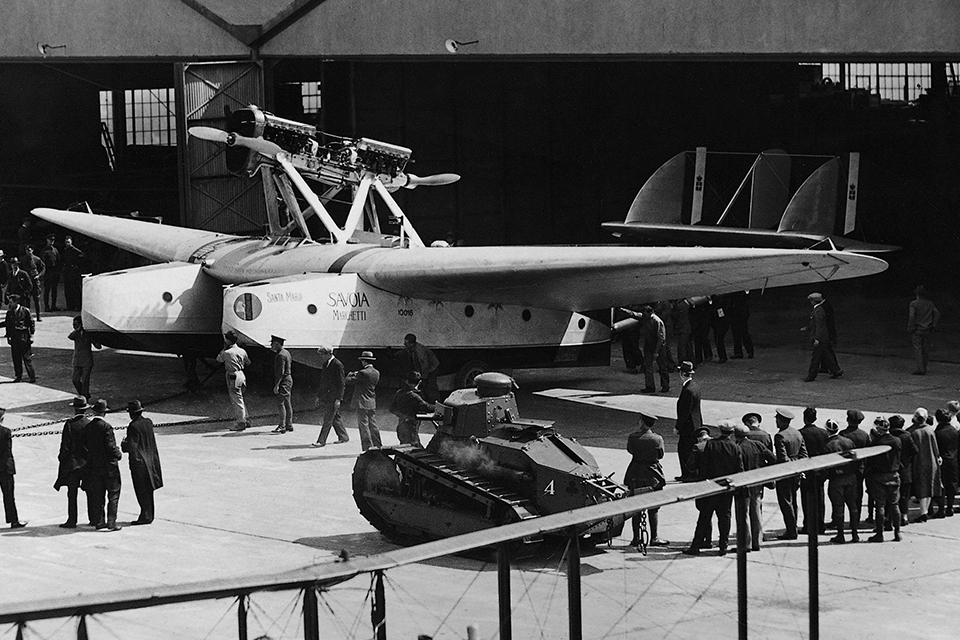

De Pinedo’s next venture, enthusiastically supported by Mussolini and the new air minister, Italo Balbo, was a double crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, beginning in the South Atlantic and returning by a northerly route. For this de Pinedo selected the unorthodox but proven Savoia-Marchetti S.55 catamaran flying boat, powered by two Isotta-Fraschini engines mounted in tandem above the cantilever wing. Accompanying him were copilot Captain Carlo Del Prete, an experienced long-distance flier, and mechanic Lieutenant Vitale Zacchetti. Their S.55 was named Santa Maria in honor of Christopher Columbus.

Leaving Italy on February 8, 1927, Santa Maria flew by stages down the West African coast before heading out across the southern Atlantic from the Cape Verde Islands on February 20. Bad weather forced them down after 1,500 miles off the Brazilian island of Fernando de Noronha. They reached Rio de Janeiro six days later and Buenos Aires on March 2. There the airmen were feted while the S.55’s engines were changed in preparation for the long flight northward across

South America.

Departing Buenos Aires on March 14 and lacking adequate maps, Santa Maria’s crew navigated mainly by dead reckoning and overnighted at river refueling stops. They crossed the Caribbean via Guyana and Cuba, arriving in New Orleans on March 29.

Heading west, Santa Maria alighted near Roosevelt Dam, in Arizona, on April 5. During refueling a cigarette butt tossed into the water by a careless spectator ignited residual gasoline on the surface. De Pinedo watched in horror from the shore as Santa Maria was consumed by the flames and his two companions leapt overboard and swam for their lives.

Air Minister Balbo immediately ordered a substitute S.55 shipped to New York, and the U.S. Army Air Corps flew de Pinedo and his crew there. When Santa Maria II arrived in early May, the punctilious de Pinedo returned to New Orleans to restart the flight. The Italians then headed north to Chicago, Montreal, Quebec and Trepassy, Newfoundland, from where, on May 30, they set off across the North Atlantic for the Azores.

Strong headwinds caused Santa Maria II to run out of fuel and force-land in the ocean 200 miles short of the Azores. Taken in tow by passing ships, the crew spent three uncomfortable days on board before they reached Horta. Resuming the flight on June 10, the ever-scrupulous de Pinedo backtracked to their ditching position before setting course for Lisbon, Barcelona and finally Rome. They arrived to an ecstatic welcome on June 16, having covered roughly 26,000 miles in the two Santa Marias.

A delighted Mussolini promoted de Pinedo to general and named him “Lord of the Distances.” Balbo soon invited him to lead the first of his justly celebrated “air cruises” by massed formations of flying boats around the Mediterranean.

Not long after, de Pinedo’s star began to fade. Having fallen out with Balbo, he resigned from the air force in early 1933. September 3 found him at Floyd Bennett Field in New York, nattily dressed in a business suit, bow tie and derby hat. After making a short speech de Pinedo clambered into the cockpit of his specially modified Bellanca J-3-500 monoplane Santa Lucia, intent on setting a new distance record by flying solo 6,000 miles nonstop to Baghdad.

Minutes later de Pinedo was dead, engulfed in flames when the Bellanca, with more than 1,000 gallons of fuel on board, swerved and crashed during takeoff. The Lord of the Distances had made his last flight.

Longtime Aviation History contributor and Royal Air Force veteran Derek O’Connor passed away on May 10 following a lengthy battle with Parkinson’s disease. We are grateful to his son Anthony for allowing us to continue his legacy with this article.

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!