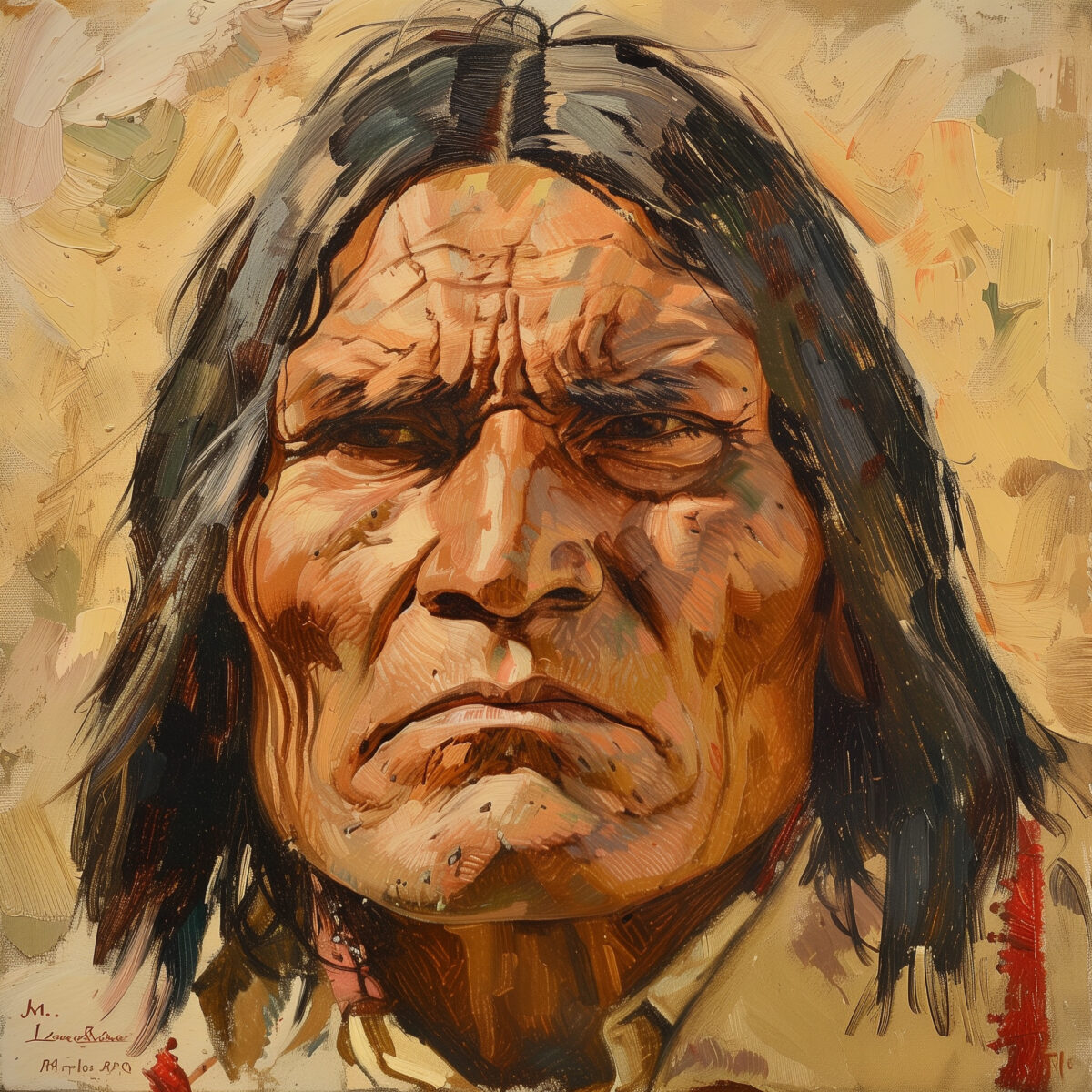

The news was a stunner: Geronimo had converted to Christianity. The story made headlines around the country in July 1903. The New York Times declared that the once-feared Apache war leader and medicine man had publicly confessed his many misdeeds while on the warpath and become an “enthusiastic worshiper.” The Times article added: “He has issued a proclamation to his people urging them to give up dancing and other worldly amusements and repent of their sins. Geronimo’s change of heart has caused a sensation among the Indians of Oklahoma and Indian territories.”

Could it be true? Geronimo a Christian? A follower of Jesus Christ? Impossible, said skeptics, who claimed they knew exactly what the cunning old warrior was up to.

Geronimo had declared his allegiance to the Reformed Church of America, a nearly identical offshoot of the Dutch Reformed Church. The latter’s most famous member was none other than U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, to whom Geronimo made repeated pleas for executive clemency. He’d been a prisoner since his surrender in 1886, and 17 years later Geronimo’s fondest final wish was to return to his Arizona Territory homeland to die. But first he had to convince Roosevelt of his change of heart.

At the time, Geronimo was a detainee at Fort Sill, Oklahoma Territory—an old man who supported his whiskey habit selling handmade bows and arrows to tourists. But to the non-Indian world, he’d always be seen as bloodthirsty, cruel and irredeemable, the very embodiment of Apache terror. Geronimo haters saw his “awakening” as another plot by this intelligent and supremely adaptable man, an extension of his diabolical wartime ways. But several modern historians, including Angie Debo, author of the 1975 biography Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place, have looked beyond caricature and see his conversion as something simpler and painfully ordinary—the effort of a flawed man to find hope at the close of his life.

The conquered Apaches arrived at Fort Sill in 1894. Missionaries from the Reformed Church came a year later and converted Chief Chihuahua and the former scout Chatto. But the most important Apache convert, the one who would have exerted the strongest pull on Geronimo, was Naiche, son of Cochise, viewed as the Apaches’ ultimate leader. Naiche held so steadfastly to his new faith that he was called Christian Naiche.

Geronimo initially brushed off the missionaries. But by 1903, with many important Apaches adopting white customs and beliefs, he was ready to go along. “Part of it was that he was losing influence with the tribe,” says Sharon Magee, author of Geronimo! Stories of an American Legend. “He wanted to be like the white man, because he thought it represented the future. But he was a very spiritual person, too, open to religion of any kind. He was a complex character.”

That summer, after a fall from his wife’s horse, Geronimo arrived at a tent meeting near the fort. In Debo’s account, Naiche sat beside a physically and emotionally frail Geronimo, then about 79, who admitted he was “in the dark…not on the right road” and wanted to “find Jesus.”

After several days of religious instruction, he accepted Christianity. “I am old, and broken by this fall I have had,” Geronimo said. “I am without friends, for my people have turned from me. I am full of sins, and I walk alone in the dark. I see that you missionaries have got a way to get sin out of the heart, and I want to take that better road and hold it till I die.”

At his baptism a week later, fellow Apaches crowded around gripping his hands, and Naiche hugged him. As the missionaries told it, Geronimo’s face “softened and became bright with joy.” But like many others with a declared allegiance to Christianity, Geronimo wasn’t particularly good at it. Missionary Hendrina Hospers said, “The old influences were too great, and his resistance to some forms of vice too weak.” The vices in question were horse racing, gambling and drinking. He was religious about those, too, and his practice of them led to his suspension from the church in 1907. Even at his most faithful—he urged Apaches to study Christianity, “the best religion in enabling one to live right”—Geronimo complained that church rules were “too strict,” and he never abandoned Apache rituals.

“He blended the two religions, and you still see a lot of that on the reservation today,” says Jay Van Orden, a former Arizona Historical Society curator. “People were skeptical of his conversion because it was so on-again, off-again. But I think Christianity was a genuine part of him.”

In his memoir, dictated to S.M. Barrett and completed in 1906, Geronimo spoke of his religious views and comes across as honest, searching and conflicted: “We [Apaches] believed that there is a life after this one, but no one ever told me as to what part of man lived after death. I have seen many men die. I have seen many human bodies decayed. But I have never seen that part which is called the spirit. I do not know what it is, nor have I yet been able to understand that part of the Christian religion.”

But his memoir also included statements that sounded like cheap flattery, providing fodder for those who thought the whole exercise an act. “I am glad to know that the president of the United States is a Christian,” Geronimo wrote, “for without the help of the Almighty, I do not think he could rightly judge in ruling so many people.”

In a 1907 interview with the Daily Oklahoman, Geronimo came right out and asked a reporter to write to Roosevelt, pleading his case for clemency: “Say to him: ‘Geronimo got religion now. Geronimo fight no more. The old times, he forget.’ Geronimo wants to be prisoner of war no more. He want free.”

Roosevelt said no, and in the end Geronimo died a prisoner of war—and a prisoner of whiskey. While returning from Lawton, Oklahoma Territory, where he’d gone to sell his bows, he got drunk and fell from his horse. He was found the next morning lying partly in Cache Creek and desperately ill with pneumonia.

In the hospital, he spoke to those keeping vigil, sometimes coherently, sometimes in visions. He imagined seeing his late grandson Thomas and Thomas’ friend Nat Kayitah, who had died days before. The boys urged him to return to Christianity. In Debo’s account, Geronimo refused, saying he’d been unable “to follow the path,” and now it was too late.

Geronimo died on February 17, 1909, and was buried in a Christian ceremony. Naiche eulogized him with kind words for his wartime courage. But he was merciless in criticizing Geronimo’s refusal to accept Christianity, “thus being an utter failure in the chief thing in life.” The New York Times also used its obituary to fire one last shot, saying that “he was all his life the worst type of aboriginal American savage” and noting that he embraced the same faith as Roosevelt to obtain his freedom. “Even his so-called religious conversion was not without cunning,” the paper snarled.

These were the words of non-Indians who couldn’t see the Apache Geronimo as a man, in the midst of his last fight. This one had nothing to do with guns or bullets. It was, in fact, a great spiritual struggle brought on by what Debo described as the “new power in his personal experience.” But, in her words, Christianity also created in him a “spiritual cleavage that was never closed.”

Originally published in the April 2009 issue of Wild West.