Despite being Robert E. Lee’s sturdy lieutenant during the Civil War, James Longstreet was vilified throughout much of the South after the war because of his Republican Party allegiance and service in President Ulysses Grant’s administration. The former Confederate lieutenant general led an almost solitary existence in his mansion set among an extensive vineyard in Gainesville, Ga. His sons had left after their mother Mary Louisa’s death in 1889, and his daughter later married a local schoolteacher, leaving Longstreet in the house with only the company of a servant.

In late July 1897, the 76-year-old Longstreet became smitten with Helen Dortch—his daughter’s friend and 42 years his junior—whom he had met in Lithia Springs, Ga. Soon the press caught wind of rumors that he might take another bride. Longstreet played coy with a persistent New York reporter before he finally confirmed the news.

“The General crossed his legs, looked out over the fields again, and replied: ‘Oh, pshaw! Well, I suppose I might as well give in,’” The New York Times reported. “I am to be married to Miss Dortch at noon on Wednesday in the Governor’s residence in Atlanta. The honeymoon is to be spent in Porter Springs, where I hope you newspaper men will leave an old man to the happiness he has acquired.”

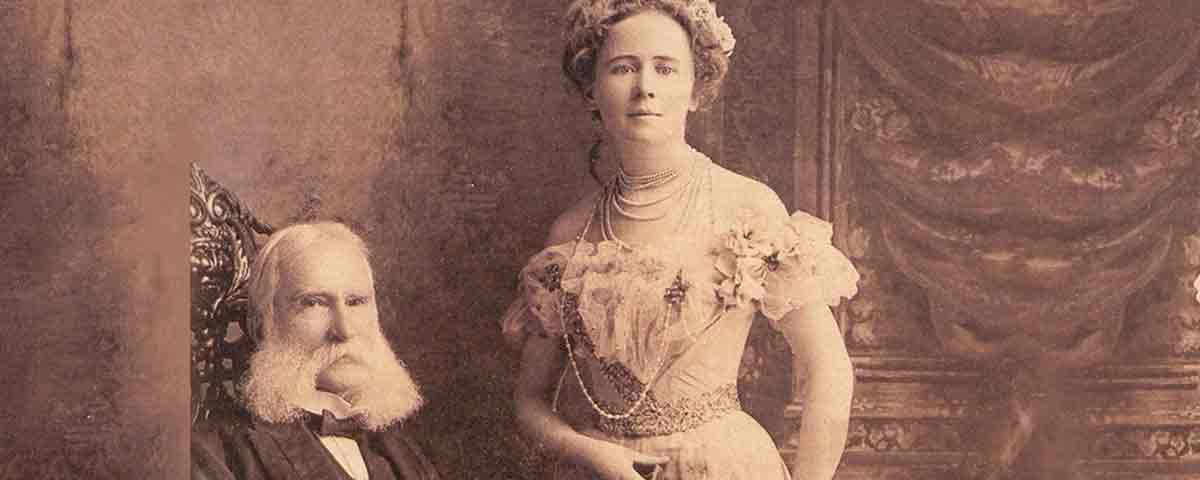

On September 8, 1897, Longstreet and Dortch—described as “pretty, piquant and sympathetic,” with blue eyes, blonde hair, and fair skin—exchanged vows in the parlor at the governor’s executive mansion.

Among those in attendance were the Gainesville mayor, a large group of Longstreet’s friends, and the general’s four sons and daughter. “They all warmly congratulated their new stepmother,” an account noted, “which should dispose of the story that there was any friction because of the marriage.”

Dortch picked the wedding date as homage to her husband, who, as an officer 50 years earlier, had heroically led his regiment at Molino Del Rey during the Mexican War.

Governor William Atkinson served as best man for Longstreet, who had converted from Episcopalian to Catholic in 1877. “When the officiating priest, after having asked the groom the question of assent, turned to Dortch to know if she would take James as her husband,” a newspaper reported, “it carried the suggestion to the groom’s heart that he was a boy again, paddling in the Savannah River.”

Newspapers were quick to point out the disparity in ages between the former general and the accomplished young woman, characterizing it as a “May and December” union. A Louisiana paper noted that although Longstreet was “a gallant and distinguished Confederate officer during the war…his apostasy since has lost him the respect and esteem of the Southern people.” Few Southerners forgave Longstreet for becoming a Republican and serving under Grant.

Another publication mentioned the general’s varied interests, and believed that his new bride, “a bright young woman,” could help manage them. In addition to a large hotel in Gainesville, Longstreet owned a vineyard and winery, raised sheep and turkeys, and had authored two books. And President William McKinley, himself a Civil War veteran, had recently called on Longstreet to serve as the U.S Commissioner of Railroads.

From her wedding in 1897 to Longstreet until well after his death at 82 in 1904, Helen would do much more than help “manage” her husband’s interests. Fiercely protective of James Longstreet, she defended the General’s reputation and memory the rest of her life—especially against critics who argued he failed to do his duty at Gettysburg. And the woman nicknamed “The Fighting Lady” led a remarkable life herself, living well into the 20th century.

The First Mrs. Longstreet

It seems preordained that Maria Louisa Garland, seen above with two of her children, would marry a soldier. Born at Fort Snelling in the Minnesota Territory in 1827, she was the daughter of Harriet and John Garland, a career U.S. Army soldier.

On March 8, 1848, Maria Louisa, better known as Louise, married Longstreet, who had graduated 54th in a class of 56 cadets at West Point in 1842. She followed her husband to many of his stops during his long military career. John, the first of the couple’s 10 children, was born in 1848 while James was on assignment at the Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania.

Louise and James were rocked by death and tragedy during the Civil War. Three of their children—Augustus, James, and Mary Anne—died of disease in Richmond in the winter of 1862. (Two other children died in infancy: William in 1854 and Harriet Margaret in 1856.)

Forged by war and family tragedy, the Longstreets’ bond was strong. When his wife became seriously ill in the fall of 1889, “Old Pete” was observed sadly walking the streets of Gainesville, Ga., the couple’s home since 1875. When asked about Louise, Longstreet became emotional. “The battle-scarred veteran, who had on hundreds of fields with unblemished cheek and unquailing eye faced death,” a newspaper reported, “became unnerved as a little child as he despairingly pointed in silent grief to the sick chamber of his wife.”

On December 29, 1889, 62-year-old Louise Longstreet died of an undisclosed illness at the Piedmont Hotel in Gainesville. “A distinguished Georgia lady,” proclaimed the headline in The Atlanta Journal Constitution the next morning. A reporter at her funeral at Alta Vista Cemetery in town observed Longstreet: “Beside the little mound of earth stood the bowed form of her husband, ‘the old war horse of the confederacy.’ Fear though he knew not, yet over the grave of his dead wife his strong frame quivered, and the stern soldier of other days stood unmanned in the presence of death.” –J.B.

Born April 20, 1863—less than five months before Longstreet led a Rebel army at Chickamauga—Helen Dortch was a woman years ahead of her time. In an account of her wedding to Longstreet, she was described as “one of the most conspicuous among the progressive women of the new south.”

At 15, she became a newspaper reporter and editor at the weekly Carnesville (Ga.) Tribune—employment that was almost exclusively limited to men at the time. “Her early journalistic experiences were not pleasant,” an account noted, “but she pluckily went forward….” She later became editor and publisher of the Milledgeville (Ga.) Daily Chronicle.

A champion for women’s rights, Dortch led an effort to open the Normal Industrial Training School for girls in Georgia. In 1894 she became the first woman to hold office in Georgia when she was appointed assistant state librarian. “I had to get the legislature to change the law before I could assume office,” she said of the so-called “Dortch Bill.” “A hundred thousand women signed a petition that the law be repealed so I could be appointed.”

Shortly after James Longstreet’s death, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed the widow postmaster of Gainesville, a significant position at the time. “It is safe to say,” the Atlanta Constitution reported, “President Roosevelt could have made no appointment that would have proved as universally popular.”

Throughout her life, Dortch was active in environmental and political causes big and small. In 1910, she was founder of a movement to erect a monument to the slaves of the Confederacy—a long-shot effort if there ever was one. In an eloquent speech, she said:

“I shall pray that I may live to see a monument at every capital in the south to the slaves of the confederacy. They wrote a story of devotion and loyalty that has no parallel in the history of man. While their masters were engaged in that struggle, the results of which would leave a helpless race free or in shackles, they worked for, guarded and defended the children of the confederacy with a fidelity that should be recorded in letters of gold across the bosom of stars.”

Not surprisingly, the monument was never built.

For years after her husband’s death, Dortch also backed efforts to have a monument placed in her husband’s honor in Gettysburg. That effort would fail, too, during her lifetime.

In 1943, at the height of World War II, the widow Longstreet took a job as a riveter at a B-29 aircraft factory in Marietta, Ga. She was 80, described as “frail but vivacious,” yet was determined to contribute as she could. “This is the most horrible war of them all,” she told a reporter. “It makes General Sherman look like a piker. I want to get it over with. I want to build bombers to bomb Hitler.”

Dortch refused to give her age to the reporter, claiming only that she was “older than 50,” and added: “Never mind my age. I can handle that riveting thing as well as anyone. I’m intending to complete in five weeks three courses which normally take three weeks.”

She lived in a trailer camp near the factory and spent long hours in training to learn her craft. “I could not stay out of this war,” she said. “It’s not the soldiers fighting soldiers like it used to be. It’s a war on helpless civilians, on children and the infirm. They are the ones who suffer. Lee, my husband, and many another southerner proved that Americans surrender only to Americans, so we are bound to come out victorious.”

Helen defended the General’s reputation and memory the rest of her life.

Her work was praised by plant officials, but a union, with which she had some difficulty, called her a “very old lady” and accused the company of hiring her as a publicity stunt. Nevertheless, Dortch stuck it out for nearly two years, and a foreman said her work ranked among the best done at the plant.

After the war, Dortch also became a vocal supporter of civil rights for blacks, and in 1950 she ran for governor of Georgia as a write-in candidate. In challenging incumbent Herman Talmadge, the “scrappy widow,” a newspaper reported, vowed to stand up for blacks and “unhood the ruffians” of the Ku Klux Klan. “I’ll make this state a place where the humblest Negro can go to sleep at night,” she said, “and be assured of waking up in the morning, unless the Almighty calls.”

Running naturally as an independent, the 87-year-old Dortch lost badly. Talmadge won reelection with 98.44 percent of the vote.

In the last 10 years of her life, Dortch’s health gradually declined, and by her early 90s she was completely deaf. After a visit to a relative in Georgia in 1956, she took a bus trip back to a health resort in Danville, N.Y., where she often lived. During a stopover in Pottsville, Pa., she told stories of “her husband’s exploits and was given a big hand when she left.” Donning her best hat, she posed for photographers. “I’m just 39, still a young belle,” she said as she departed.

Probably suffering from dementia, however, she was removed from the bus in Elmira, N.Y., after the driver told authorities she had been annoying passengers. Taken in by the Travelers Aid Society, she wandered away and later was taken into custody by police for her own protection. A city health officer said Dortch seemed “irrational and incoherent.” She was hospitalized in New York before being sent back to Atlanta.

Six years later, on May 3, 1962, Helen Dortch Longstreet died in the Milledgeville State Hospital, once the largest insane asylum in the world. According to doctors there, she seemed “perfectly happy.” The woman who had defied convention and never liked to reveal her age was 99.

John Banks is author of two books on the Civil War, Connecticut Yankees at Antietam and Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers, both by The History Press. He also is the author of a popular Civil War blog (john-banks.blogspot.com). Banks lives in Avon, Conn.