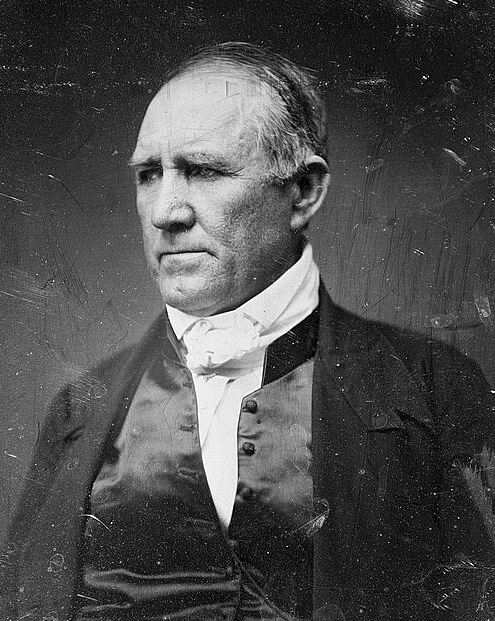

Shaking his left fist to emphasize each word, the governor of Texas proclaimed with rising volume, “States’ rights! States’ rights! States’! Rights!” This wasn’t the 1960s when Southern governors used that phrase to defend Jim Crow against federal civil rights laws. It was April 15, 2009, and the incumbent governor Rick Perry was speaking to a Tea Party crowd in Austin, Texas, during what turned out to be his successful reelection campaign. Perry is a handsome man and this day, in a beige jacket with the collar turned up and a dark blue baseball cap pulled down over his forehead, he looked particularly grim, angry and defiant. “Texans know how to run Texas,” he continued. He quoted Sam Houston, who led a ragtag army to victory over Mexico in the Texas War for Independence in 1836, saying, “Texas has yet to learn to submit to any oppression come from what source it may.” Perry paused and added, almost as a battle cry, “We didn’t like oppression then. We don’t like oppression now.”

Perry subsequently earned national attention by suggesting that, if things don’t change in this country, Texas could just secede. For better or worse, it’s impossible to imagine a governor of any other state making such a threat. But for anyone who lives in Texas, as I have for 50 years, this kind of political rhetoric is not at all unusual, even if plenty of us think Perry would do well to remember that when Sam Houston served as governor on the eve of the Civil War, he tried in vain to keep Texas from joining the Confederacy. Texans like to hear that we are a breed apart and that we not only deserve to follow our own destiny but are also determined to follow it no matter what the opposition. Texans like to hear that by doing things our own way we can and will prevail. If questioned, we tend not to answer but to defy. From 1979 to 2000, Johnny Holmes was district attorney of Harris County, which contains the city of Houston. He became famous for the number of death penalty convictions he obtained. “When one of the national television news programs was pushing me about why we sent so many people to death row,” he said in Texas Monthly, “I told the anchor that it’s nobody’s business but Texans’. I said, ‘I don’t give a flip how you all feel about it.’ ”

Our combination of independence and belligerence is founded on a hallowed past with brilliant heroes, or at least that is how the story is told every time there’s an election. Texans believe in their own revolution, which culminated in the birth of the Republic of Texas 175 years ago and statehood roughly a decade later. They believe in its virtue and its honor and its heroism, perhaps even more than the rest of America believes in the American Revolution. Texans are Americans, of course, but they consider themselves Texans, first and foremost, and embrace a founding mythology that fosters the illusion they are living in a separate country.

By Texas law, the story of the revolution must be taught in Texas schools. School children are required to take Texas history, not once but twice—in the fourth grade and again in the seventh. There is nothing wrong with children learning the past of the place where they live, but here that past is given a weight and even a reverence that is out of proportion to its real importance. It is true that some people important in the history of Texas are also important in the history of everywhere else. Lyndon Johnson is one example. But for the most part, the great heroes of Texas (there are some heroines, but they are few) are giants only here and nowhere else. Do you know these names—any of them—James W. Fannin Jr., Benjamin “Old Ben” Milam, William Barret Travis, Juan Seguin, James Butler Bonham, Erastus “Deaf” Smith or Mirabeau B. Lamar? If you are not from Texas, these names most likely fall on your ears with a dull thud. But Texas school children know them all, at least in theory. And so do most Texans even if only in a hazy way, since these are common street names in our cities, especially Houston.

Here, for the uninitiated, is a cheat sheet on those men. James W. Fannin Jr. was a luckless officer who failed in his attempt to reinforce the Alamo and later died in the massacre at Goliad. (Non-Texans have probably not heard of Goliad either.) Old Ben Milam rallied the insurgent Texan troops who were besieging the Mexican army in December 1835 with the cry, “Who will follow old Ben Milam into San Antonio?” The troops surged forward and took the town, which is how the Texans happened to be in the Alamo when Mexican reinforcements under Santa Anna arrived a few weeks later. William Barret Travis was the commander of the Alamo. Juan Seguin was of Mexican birth but sympathized with the rebel side in the revolution and died in the Alamo. James Butler Bonham snuck out of the Alamo as a messenger and managed to break back through the Mexican lines with about 40 reinforcements a few days before the final battle. Deaf Smith was a trusted scout for Sam Houston. Mirabeau B. Lamar was the first vice president and the second president of the Republic of Texas. In addition to glorified heroes, there are glorified events in Texas history that are important to the state but little known elsewhere: the Come and Take It fight, the Runaway Scrape, the Battle of San Jacinto. The list could be extended for miles, but with mighty effort I will restrain myself.

Texas history really is unique compared to the history of the other 49 states. In our schools that history is taught, not exactly incorrectly, as a past that gives Texans a certain entitlement. When Anglos in large numbers began to migrate into Texas, most of them coming from the Southern or Midwestern states, they were not entering an ungoverned, unclaimed wilderness, nor were they entering a territory administered by the United States. Instead, they were entering a foreign country, namely Mexico.

During the 1820s and 1830s, Mexico’s hold on the piney woods west of the Sabine River was hardly firm, consisting in a small town or two here and there. San Antonio, the administrative center of a vast territory, was a grubby, muddy frontier outpost of only about 2,000 people. In the endless plains north and west of San Antonio, the most powerful force by far was not the Mexican government but the Comanches who roamed and raided at will.

The Comanches were one reason that Mexican citizens in that era hesitated to move north of the Rio Grande in significant numbers and colonize Texas. In fact the government in Mexico City had some justifiable fears that the Comanche raiders, who appeared to be growing stronger with each day they remained unchecked, would cross the Rio Grande and invade the south. A second reason Mexican colonization was sparse was that the land in northern Mexico and far south Texas is arid, hot, rocky and forbidding. The many illegal migrants who have died in recent times coming north toward Texas testify to the difficulty of travel through this territory.

At the same time, Anglos looking for land were entering Texas illegally from the United States, where the passage through Louisiana or Arkansas was not as dismal as entering from the south. The Anglos settled wherever they thought they would be safe from interference from either the Mexicans or the Comanches. Letters from the era describe land in Texas, here meaning the land just west of the piney woods, as “beautiful” or “rich.” That’s not how the traveler would describe it today, but that’s because today’s traveler means “scenic” when describing something as beautiful. In the first part of the 19th century, beautiful land was land that invited farming. And the land in Texas seemed created specifically for that purpose. These early settlers found a large, spreading, coastal plain laced with gentle rivers that flowed clear to the Gulf of Mexico. “Many immigrants to Texas came from Tennessee, where the stony ridges and thin soil tested the patience of even the Jobs among the plowmen,” writes historian H.W. Brands. “At first feel of the deep black earth along the Brazos and Colorado and Guadalupe, these liberated toilers fell in love.”

Faced with the ravages of the Comanches and the unchecked illegal immigration of the Anglos, the Mexican government envisioned the Anglo settlements as a potential buffer—or bait—for the Comanches and granted men known as impresarios the right to settle a number of families in large areas on the coastal plain north of the Gulf. The greatest of these impresarios was Stephen F. Austin, but there were others. In 1824, Austin succeeded in settling nearly 300 families on fine farming land in southeast Texas. These settlers are known now as the Old Three Hundred. Many of their family names such as Kuykendall, Bryan, McCormick, McNair, Bell and Borden are still prominent in Texas today. In the next 10 years, Austin brought about 1,500 Anglo families to Texas. Due to his efforts, the work of the other impresarios and the large numbers of people who arrived illegally on their own, by the early 1830s there were some 20,000 English-speaking settlers (and their slaves) in Texas compared to only about 4,000 people who spoke Spanish.

The newcomers were required to give up their American citizenship and become citizens of Mexico. Most of the Anglo settlers were Protestant. To become Mexican citizens, they were supposed to become Roman Catholic as well. Sometimes, the Anglos simply ignored these laws, but there were other regulations and taxes that antagonized the colonists. When the Mexican government, realizing a little late that they had created a monster by inviting these Anglos in, tried various means of enforcement, revolution was ignited. One can argue that the Mexican government was more obstinate than oppressive, but these new settlers came from a tradition of revolution. They bristled when a—to them—foreign government interfered with their lives and what was now their land. Federal taxes and regulations inspire the same resentment in Texans today. They may inspire resentment in the rest of the country as well, but a Texan can claim, as Governor Perry has repeatedly, that these are the kind of intrusions the Texas Revolution was fought to repel.

Although there had been grumblings for a decade at least and even a few skirmishes, real revolutionary fever spread during the last months of 1835. At that time Stephen F. Austin toured the South making speeches appealing for aid for the war in Texas. Austin had formerly been more cautious, as had his colony’s largest landowners, who had the most to lose. But circumstances forced him to pick sides, and he chose Texas over Mexico. Once his choice was made, he became a fervent proselytizer, eloquently defending the rebellion by connecting it with the American Revolution that was then just 60 years old. But, according to Austin, the Texas Revolution was even more necessary and righteous than the American. In Louisville he proclaimed that the war in 1776 had been against “a principle, the theory of oppression.” In Texas the revolution was against a reality. It was against “a denial of justice and our guaranteed rights; it was oppression itself.” And to whom did the land belong? To some king or foreign power who claimed it or to the people who had conquered the wilderness to settle there? The answer was clear. Texas belonged to the Texans and to no one else. “The true and legal owners of Texas, the only legitimate sovereigns of that country, are the people of Texas.” That statement was incendiary then. It gave a logical reason for taking up arms. Even today, few Texans would disagree with it.

In 1836, the Anglos managed to create an army and conduct a war. Rather against the odds, they picked up the pieces after the Alamo fell and Sam Houston led them to an intoxicating victory at the Battle of San Jacinto. Now they were not living in Mexico, and they were not living in the United States. They were living in a country of their own creating that they had taken in battle. The delirium of that victory has not receded. Skillful Texas politicians use it to stir their crowds even today.

Texans still think they are living in their own country and believe they have a right to. The state capitol building in Austin, built in 1888 and taller than the Capitol in Washington, does fly the American flag above the Texas flag atop its dome. Also, every session of the legislature begins with the Pledge of Allegiance, followed immediately by a pledge to the Texas flag. But those are the only nods toward federal authority anywhere to be seen. Memorial statues on the grounds commemorate the heroes of the Texas Revolution and of the Confederacy. Cannons, supposedly used in revolutionary battles, guard the doorways. Inside, the names of major battles of the revolution are inlaid in the floor, and the walls are covered with heroic paintings of the Battle of the Alamo or the Mexican surrender to Sam Houston. Battle flags from the revolution hang in the legislative chambers. It’s an impressive and beautiful building that makes you think that Texas is something more than a state, a building where it’s easy to forget that Texas is also less than a country. And that is where our legislature meets to deliberate.

No wonder we are headstrong. No wonder Governor Perry floated the notion that Texas might secede again. No wonder that Texans often radiate a feeling of entitlement and talk as if Texas were exceptional among all the other states. And no wonder non-Texans, having seen that attitude one too many times, want to take it down, want to knock the cowboy’s hat off.

The revolution is the primary reason, but not the only reason, that Texans feel unique among all Americans. It’s a tired old joke that Texas, and everything in Texas, is big. Yes, the sheer size of the place has had a deep effect on the Texas soul, but it also disguises something more important. Despite the size, the geography of the state is relatively uniform. Yes, it can be freezing in Dalhart at the northern tip of the panhandle while it is hot in Brownsville 759 miles away at the southern tip. And, yes, the rainy piney woods in the east give way to rolling limestone hills, that in turn, just west of Austin, give way to flat and mostly arid plains. But between those extremes of weather and landscape, there is a sameness across a vast territory that is remarkable. Drive from San Antonio to Dallas, about 280 miles, and you won’t see any change worth noting. During the summer, go to any place south of the panhandle and it’s hot as the sun bakes the land. During the winter, go to any place north of San Antonio and it’s cold as the wind roars across the prairie. The uniform climate is one reason there is a recognizably Texan way of dress. Jeans and pearl snap shirts can go most anywhere any time of year, and a hat with a broad brim keeps off both the summer sun and winter rain.

Similar land and similar climate make for a similar experience of the natural world, so much so that it’s not unusual for a Texan who lives in the city to pose as someone who lives in the country. One common fault among Texans, seldom understood by outsiders, is that we can easily fool ourselves that a role we adopt is actually true. A lawyer, say, who has spent his life in a large downtown firm in Dallas, but who owns a house on a piece of land in the country, comes to think he is a rancher. Even people without country land may think they are ranchers. They are ranchers who just don’t happen to own a ranch.

The effect of this and other, similar widespread delusions is that while Texas is overwhelmingly urban by population, the mentality of the state is basically rural. Certainly, a rural mentality rules the legislature. It’s true that currently the lieutenant governor comes from Houston and the speaker of the house comes from San Antonio. But the governor and many of the important committee chairs are from rural areas and, again, the people who live in the cities often think, act and vote as if they lived in the country. That’s why in the Texas legislature, outsiders, fancy pants, intellectuals, artists and the federal government are viewed not just with suspicion but often with hostility. By the same token, anyone who wears boots, even if only figuratively, and who glibly broadcasts the accepted political wisdom, which these days is a know-nothing belief in the free market and complete faith in guns, can easily con legislators so completely they will walk sideways to do his bidding.

Texas is far from an intellectual or cultural wasteland. Dallas and Houston have impressive museums, symphonies and opera companies. And in San Antonio and Houston and especially in Austin, the local music scene is vibrant. There are outstanding universities and active cultural organizations of all descriptions. And culture reaches out from the cities, far into the country, especially in the wide, lonely spaces of west Texas. All that activity and talent is why I’ve lived here for as long as I have. But all that is despite state government, not because of it. Such things become even more beside the point when the budget gets tight.

When it comes down to it, I agree with our governor that Texas is exceptional. But I differ from him and others who are now running our government about what exactly is exceptional about the state.

In history, Texas is where Anglo culture and Latin culture met and clashed. There are still ugly vestiges of that clash, but there are also beautiful vestiges of the mixture that resulted, and you see them in food, in song and in architecture. The Latin culture has smoothed the Anglo culture and made it more aware of, among much else, romance. Think of the Everly Brothers’ song “Bye Bye Love.” In Spanish it’s a more mellifluous “Adios, Adios, Amor.”

Most of all, and this is precisely what is exceptional about Texas, I feel I am living on the Texas frontier, never mind my books and stereo system and air conditioning and other citified comforts. There’s no land for the taking in Texas anymore, so Texas is not a frontier in that sense. But it is a frontier in the sense that this place has yet to be formed. After the victory in the revolution, Texas took its destiny in its own hands, and despite annexation and statehood, despite secession and statehood again, Texas has never let that hold slip away completely. Texans are exceptional because they are part of a grand, historic endeavor to become…what? Well, that’s what we’re working out.

Gregory Curtis was the editor of Texas Monthly from 1981 to 2000. He is also the author of The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World’s First Artists (Knopf, 2006). He lives in Austin.