American who fought for Canadian independence did hard labor in Britain’s convict colony

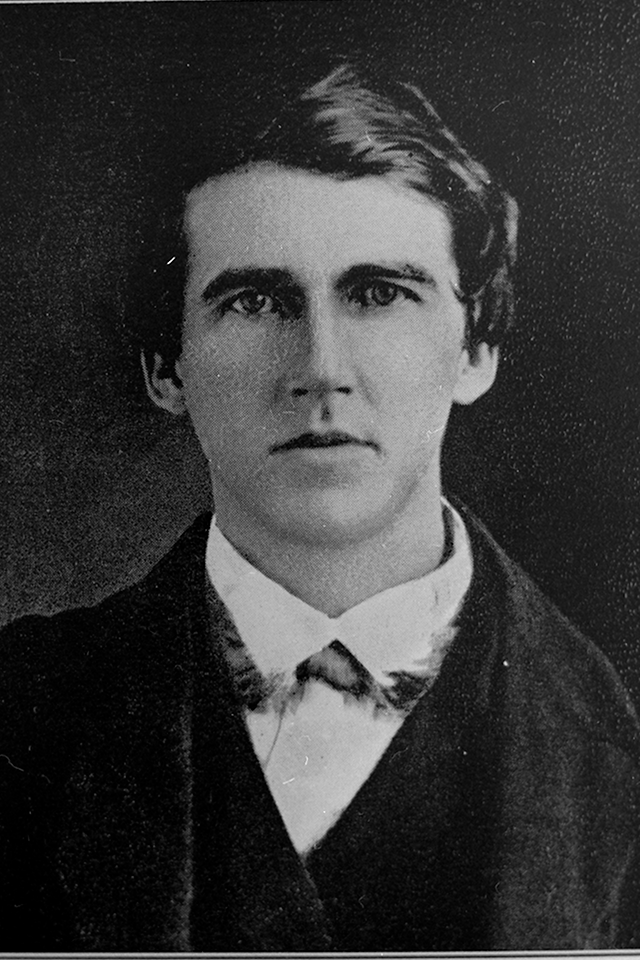

ON SEPTEMBER 24, 1845, a late afternoon sun was lighting the waterfront sandstone warehouses of Salamanca Place, commercial hub of Hobart Town, the capital of Australia’s far south island, Van Diemen’s Land. Linus Wilson Miller, an American citizen, stood alone in the dockyards gazing at whalers and other vessels riding at anchor. The slim, cocky 24-year-old, a native of Stockton, New York, was to sail the next day, a free man returning to his homeland. Seven years earlier, Miller had entered into a desperate enterprise that led to trial, brutalities, and confinement in Canada and England, and finally prison in Australia’s penal colony on the island, better known to its convict population as “Van Demon’s Land.”

Miller’s odyssey started December 5, 1837, with an armed populist uprising in Toronto, in what was then the British Colony of Upper

Canada. Rebels, some armed only with pitchforks, wanted more representation in their government, at the time controlled by the lieutenant governor in cahoots with a ruling oligarchy. Amid a dire economic crisis gripping the region as well as the adjoining portion of the United States, Canada’s elite, the rebels claimed, were denying ordinary people, many of them out of work and destitute, a say in land policies, religion, and politics. Upper Canada was split between its haves and its have-nots.

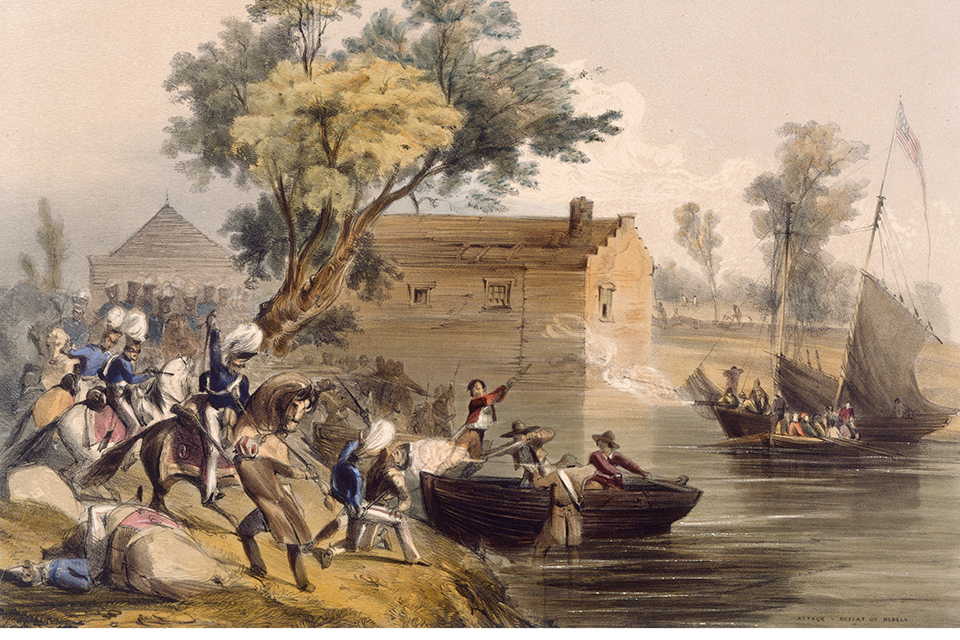

Authorities quickly quashed the Toronto uprising. Many rebels and their leader, William Lyon Mackenzie, crossed the Niagara River into the United States, where their cause had sympathizers. At Buffalo, New York, Mackenzie fired up more support, and with their newfound allies he and his men seized and fortified British-owned Navy Island, a speck in the Niagara—declaring the island to be the new “Republic of Canada.” Canadian militiamen and red-coated British regulars harassed the rebels with cannon and musket fire. For supplies, the insurrectionists were relying on Caroline, a privately chartered steam vessel flagged in the United States. Rebel resolve persisted until the night of December 29, 1837, when a Canadian attack sent Caroline drifting in flames toward Niagara Falls. One man died. “BUTCHERED IN COLD BLOOD” shrieked the Buffalo Journal, dramatically multiplying the number of casualties. Similar exaggeration by border newspapers from Michigan to Vermont fired and reinforced the emotions of young American men, many as adrift as their Canadian cousins. As young Buffalo diarist Mary Peacock wrote, “The war in Canada has so affected and excited the people in this city that it is a subject of some doubt where it will end and in what manner…”

To settle matters on Navy Island, U.S. President Martin Van Buren dispatched General Winfield Scott. The celebrated military leader convinced the rebels on the island to relent.

However, an underground paramilitary calling itself “the Hunters” had formed secret lodges in border states. Unemployed fellows, some acting out of democratic impulse, others drawn by the outfit’s promises of land and gold, swelled the Hunters’ ranks.

Asserting themselves to be servants of Canadian independence, Hunters and other Americans organized into an amateur “Patriot Army”

that through 1838 carried on a sustained, if ramshackle, campaign of cross-border raids, each in succession defeated by superior British forces.

Hazel-eyed Linus Miller, six feet tall and 20 years old, with brown hair and whiskers, joined one such invasion. An upstate country boy from Stockton who wanted to be an attorney, he was in Maysville, New York, reading the law when he surrendered to the excitement spreading across New York’s western frontier over Canadians’ determination to establish their own government. Miller volunteered to join the fight. He crossed onto the Canadian Niagara Peninsula in advance of a Patriot Army invasion planned for July 4, 1838.

When the attack stuttered and failed, Miller tried to return to the United States but found the border too closely guarded. He rejoined the raiders, now being pursued by loyalist militia. “Little did I dream of the dark cloud which was fast gathering Sover my head,” he wrote later. Miller hid in patches of woods until he had no choice but to take to the open road, where a pair of British cavalry officers took him prisoner. On trial for his life at Niagara on charges of sedition, Miller, drawing on his legal training, at first made a bold defense, but then, at his lawyer’s suggestion, pleaded insanity, to no avail. After hanging insurgent James Morreau, Canadian authorities set a date of August 25, 1838, to hang Miller and three compatriots. “There was no bitterness in the thought; no regret that I had joined my fate with the struggling Canadians,” Miller wrote in his basement cell. “For conscience told me I had done my duty, fearlessly and faithfully.” Intercessions by friends and family led officials to commute his death sentence and 12 others to transportation to Van Diemen’s Land—now Tasmania—for life (see “Propulsive Punishment,” below). Miller felt relief but, he wrote much later, “could I have foreseen one fourth part of the sufferings which that commutation entailed on me, I would have preferred immediate death.”

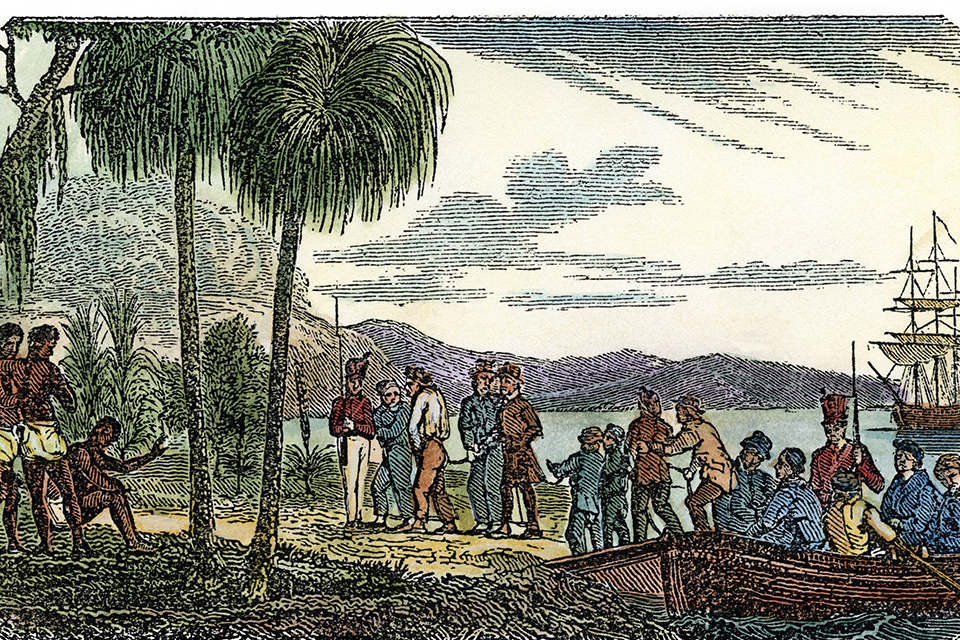

The prisoners to be transported were held for nearly three months at Fort Henry near Kingston, Canada, before being shipped by steam vessel to Quebec.

On November 22, 1838, riveted into irons pinioning them hand and ankle, 33 rebels were ferried to the three-masted Captain Ross, about to depart Quebec harbor for Liverpool, England. The men crowded into a fetid, dark hold 12 by 14 feet. “I was horror stricken,” Miller wrote.

“I always knew they meant to kill us, but didn’t think of being buried alive in such an infernal hole as this!”

The prisoners were 25 days crossing the Atlantic. Britons had been following the Canadian border disturbances in sensational newspaper coverage, so when the shackled North Americans stepped onto a quay at Liverpool on a chilly December morning they had an audience. Wagons carried the prisoners to a jail where, in a spacious yard, guards unshackled and unchained the men. Magistrates addressed them in not unkindly terms. “We were soon made to feel that we had come less to a land of strangers than of friends,” Miller wrote. He and his companions expected their sentences to be appealed in habeas corpus hearings, but for that to occur the convicted rebels had to travel by train to London, arriving in January 1839 at Newgate Prison. “The massive doors were unbarred to welcome us,” Miller wrote. “We were again buried in a living tomb.” Daily guards released the men for appearances in Westminster Hall. In May the court upheld Miller’s and many others’ convictions, remanding the prisoners to custody to await transportation. “During this long and anxious period, our suffering arising from hope deferred and the uncertainty of the future, were often intense and severe,” the former rebel wrote.

From London authorities moved the convicts to Portsmouth, in Miller’s words “an exceedingly filthy seaport town.” Fellow prisoners rowed them to York, a Royal Navy man-of-war reduced to service as a prison hulk. Trusties removed the prisoners’ irons, sheared their hair, confiscated all money and tobacco, and ordered them to strip and wash in a large, dirty cistern, “in which the whole van-load of prisoners had cleansed their filthy carcasses,” Miller observed.

Until they sailed for Australia, prisoners awaiting transportation had to work at hard labor. Miller “began to learn that a prisoner must have no will of his own, no feelings, no soul: the discipline to which he is subjected, being intended not only to torment the body, but to crush and destroy all those attributes which constitute the man as distinguished from the brute.” Nightly, exhausted, cold and hungry, hands and feet blistered from toil, the men of York squeezed into tiny hammocks to roost. Meals were as squalid as the conditions: porridge for breakfast, a ship’s biscuit for lunch, dinner of a pint of watery soup, a half-pound of salt beef that was mostly bone, and a pound of “brown tommy” bread. “I do not exaggerate, when I assert that swine, in my own country, would not eat it unless half starved,” Miller wrote.

In September 1839, York emptied its human contents into the 500-ton merchantman Canton for passage to Van Diemen’s Land and the intervening punishment of sea travel. “No sooner were the sails unfurled, than sea-sickness commenced, and in a short time became general,” Miller recalled. “‘Accounts were cast up’ without ceremony, not only on the floor but in the berths; and our apartment was rendered truly horrible. An entire week passed before it could be properly cleansed.” Miller and fellow rebel prisoners were traveling with civilian felons who also were paying for their crimes with transportation for life.

The voyage, by way of Africa’s southern tip, took months. The climate shifted from the temperate zone’s cold and winds to calm, insufferable heat in equatorial waters. As political prisoners, Miller and companions enjoyed small entitlements resented by the 240 thieves and murderers also aboard. The other men made their ire known. “The most horrible blasphemy and disgusting obscenity, from daylight in the morning till ten o’clock at night were, without one moment’s cessation, ringing in my ears,” Miller wrote.

Time crept by, slowed in perception by confinement, rampant dysentery, and seasickness. Two men died; with shot-weighted hammocks for coffins, they were committed to the deep. “The board was raised, a plunge succeeded, and the slight ripple of the parted waves, as we sailed on, soon disappeared,” Miller wrote in his memoir.

A lookout sighted mountainous Van Diemen’s Land in January 1840, signaling the imminent end of a pounding four-month, 16,000-mile voyage. Their first day ashore, bodies swaying on sea legs, the convicts formed a ribbon staggering toward the “Tench,” as Hobart

Town’s massive stone prison compound was known. A man died; ordered to bury the corpse, Miller wrote, friends found the unfortunate’s body “cut in many pieces, with its entrails lying beside it. They gathered up the pieces together and put them in a coffin of rough boards… carried him away and laid him in a stranger’s grave…”

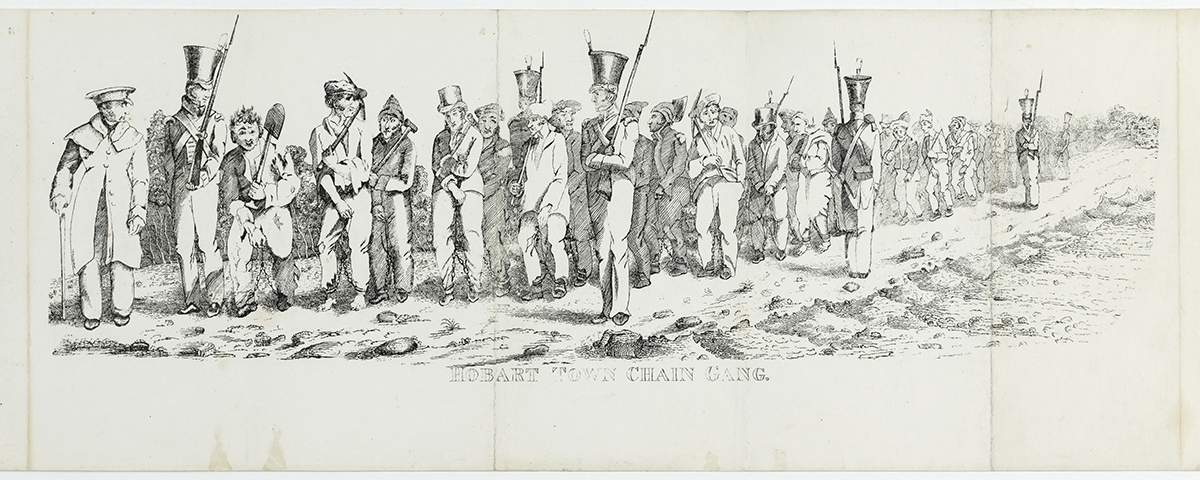

Summoning memories of his legal studies, Miller drafted a petition requesting liberal treatment for political prisoners. The authorities denied the petition, sending the former rebels into the “probation” system—two years as gang laborers. Their first task was felling, trimming, and shaping trees into ships’ spars and hauling the finished product to the camp’s headquarters. Subsequently the men worked dawn to dark breaking and hauling stones for road building. Rations were slight, clothing insufficient, and hunger constant, according to

Miller. The punitive routine was literally killing. Nine American captives died of disease, quarry explosions, lumbering accidents, and being run over by loaded carts.

A man who displayed good behavior during the probationary period stood to earn a ticket-of-leave. Ticket holders could seek work for wages under the jurisdiction of district police magistrates. Continued good behavior could gain a prisoner a full pardon.

Miller decided to escape.

Taking insanely bold and impossible flight, Miller and fellow exile Joseph Stewart sneaked away from a probation station. The two roamed for days until, demoralized and exhausted, they fell asleep and were caught by searchers. The escape attempt drew them reassignment to Port Arthur, a fearful and barbarous place in southern Van Diemen’s Land Australia that reserved as a location at which to confine hardened criminals. “I can expect no quarter,” Miller told himself. “I am an American citizen—I am a British Slave.”

Convicts at Port Arthur worked at hard labor in the forest. The six-foot Miller felt the fullest weight of the 300-lb. logs he and shorter crewmates staggered under through dense brush. To collapse was to earn a flogging. On a visit to Port Arthur, Lieutenant-Governor Sir John Franklin pulled Miller from a lineup to berate his Yankee prisoner.

“I am glad, very glad that you are here, in my power where there is no escape,” Franklin said. “I’ll break your American spirit. I’ll break your low republican independence.” Miller felt himself give up.

However, he began to catch breaks. The station surgeon reassigned him from the lumber detail to the garden and laundry. He then clerked for the chaplain and tutored the commissary officer’s children. Good behavior and favorable impressions earned Miller a ticket-of-leave and relocation to Hobart Town, where in summer 1843 he undertook a clerkship in the law. His nemesis Franklin was reassigned, and Franklin’s replacement as lieutenant governor began to cultivate a friendship with Miller.

In February 1845 Miller received a full pardon for his 1838 infractions. Seven months later, having arranged to pay his passage by giving the ship’s captain a promissory note, Miller sailed east on Sons of Commerce. “To describe my feelings on leaving Van Diemen’s Land, would be impossible,” he recalled. “The remembrance of all my dreadful sufferings, the persecutions of my enemies, the kindness of my friends, and

the forlorn condition of my less fortunate comrades, came up before me, and I am not ashamed to acknowledge, that I paced the deck for some time, my breast heaving with uncontrollable emotions, and tears gushing from the eyes, in spite of my efforts to restrain them.”

At Pernambuco, Brazil, Miller transferred to Globe, an American bark that was bound for Philadelphia. From that city he rode by train to Stockton for a reunion with family and friends. He married, fathered five children, and spent the rest of his life farming and dairying. An unapologetic rebel, Miller lectured on the patriot experience and the horrors of transportation. When his “Notes of An Exile” was published in 1846, the first 2,000 copies sold out within weeks. “Uncle Linus” became known as “the famous adventurer of the family.” By 1880, the year Linus Miller died, Canada had reformed its system of governance and long since forgotten the Rebellion of 1837.

_____

Propulsive Punishment

Britain’s punitive system of transportation evolved out of 16th-century Poor Laws enacted during a time of widespread crime and deep poverty. A 1579 law applying to “Rogues, Vagabonds, and Sturdy Beggars,” besides enumerating standard penalties for various crimes, directed that offenders who appeared dangerous or unredeemable be committed to jail and if deemed necessary, through a further court ruling be “banished…and conveyed…beyond the seas.” Such enforcement was scant until the early 1600s, when courts sent felons and petty thieves to the American colonies to empty packed English jails. Transported prisoners were auctioned as indentured servants, providing much needed labor in the growing colonies. The 1718 Transportation Act provided for official contracts with ship owners to transport prisoners, increasing the volume of men and women sent to North America for terms of seven to 14 years, after which they could return home. The Revolution ended use of the colonies as a pressure relief valve for Britain’s social ills. As prisons overflowed, the 1776 Hulks Act provided for the recycling of decommissioned ships-of-the-line as prisons, with inmates released by day to work at hard labor, an arrangement maintained until 1857. In the late 18th century the Crown answered a renewed need for punitive transportation y designating Australia, on the Empire’s distant frontier, as a locus to which criminals of every stripe were to be banished. In 1787, the first thieves, poachers, embezzlers, murderers, and political prisoners went to Botany Bay. In 1803 transportation shifted to Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania, a flow kept up until 1853. The majority of transported prisoners died in exile or chose never to return to their homelands, making transportation a life sentence. —Stuart D. Scott