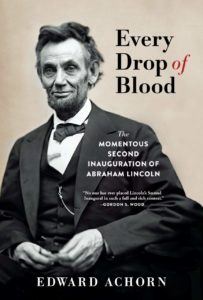

In August 1864, President Abraham Lincoln was so unpopular and the war so hated that he was certain he would not be reelected in November. In Every Drop of Blood: The Momentous Second Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020, $28), journalist and historian Edward Achorn tells the remarkable story of how Lincoln won a second term, and then on Inauguration Day gave a timeless speech in which he argued that the war had been just and that nation’s new task was to heal the wounds of both battle and bitterness.

Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020, $28

How did Lincoln turn the tide? Before the election, Lincoln was seen by Radical Republicans as a timid man who had not provided the stern leadership needed to win the war. Democrats viewed him as a vile tyrant who had all but destroyed America by throwing his political enemies, including newspaper editors, in jail without due process and by pressing to make African Americans the social equals of whites. Lincoln wrote on August 23, “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected.” Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in September finally made it seem the war might be won, and Lincoln was able to persuade the public, as he put it, that “it is not best to swap horses while crossing the river.” Finally, he worked very hard to get pro-Lincoln soldiers to the polls.

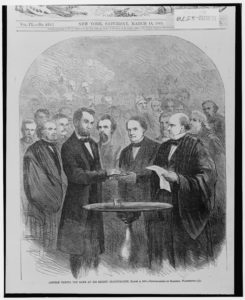

Set the scene at the U.S. Capitol on Inauguration Day, March 4, 1865. It had been raining for days, and the accumulated dirt and horse manure on the streets of Washington had turned into a watery yellow mud that splashed up on everybody and everything. Tens of thousands of people had been undeterred, though, and came to Washington to celebrate, more than filling every hotel. That morning, fierce winds tore through the city. Reporters lamented the ruined dresses of women who came to the Capitol for the inaugural events — a very big deal in those days. There was some fear that Lincoln would not be able to adhere to tradition and take the oath on the steps of the Capitol, on a wooden platform built for the occasion. But the rain let up enough for that to happen, and as he rose to give the speech the sun burst through the clouds. Many in the audience thought that providential, a sign from God that better times were coming.

In writing his second inaugural address, Lincoln spent many months trying to make sense of the war and find a way to ease the hatred that divided the states. When did this process start and how did he craft his thesis? Lincoln seemed haunted by the question of what this hellish war meant. How could a just God permit so much death and agony? How could He not side with North, which in Lincoln’s view was fighting to save the last best hope on Earth for human freedom? How could He seemingly be against both sides? In 1862, he wrote down some of these thoughts and concluded that God’s purpose might be “something different from the purpose of either party.” He mined these thoughts in the Second Inaugural Address, concluding that the war was God’s judgment on America for the evil of slavery, and the country was obligated to use all necessary means — however horrific — to finally root it out.

Lincoln believed that God would punish America—North and South—for the great sin of slavery and that he owed the country an explanation for the price it had to pay. Talk about how his religious beliefs were expressed in the inaugural address. Lincoln’s address was remarkable. He had struggled to save America at great cost and stood on the brink of finally winning this ghastly war. Yet there is no hint of triumphalism in his words. The speech is all about the suffering that both North and South had endured. One of the few things still uniting Americans in early 1865 was their intense Christian faith, including the belief that a just God watched over them. Lincoln tapped into that to make the argument that neither side had triumphed — that the war had been in God’s hands since no human could have imagined its magnitude. And God, Lincoln speculated, was using the war to end slavery. As he poignantly put it, if God willed the war to continue “until every drop of blood drawn with the lash” applied against the enslaved “shall be paid by another drawn by the sword,” the judgments of God could be deemed “true and righteous together.” It is in this context that Lincoln spoke so beautifully of binding up the nation’s wounds and proceeding “with malice toward none, with charity for all.” Both sides had been wrong. Both sides had perpetuated slavery. Both sides had to come together and move on.

Explain how the Book of Genesis’ words about tyranny formed the core of Lincoln’s moral beliefs—including his hatred of slavery and his veneration of the Union. Lincoln had always been struck forcefully by a passage in Genesis, in which God punishes Adam for his disobedience by condemning him, and his successors in human history, to lifetimes of work to survive. As God puts it, “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread.” At the core of Lincoln’s moral beliefs — at the core of his hatred for slavery and love of individual liberty — was the belief that every man deserved to keep what he had earned from the sweat of his brow. No government, no aristocracy, no slaveholder had a right to deprive a fellow human of what they had earned for themselves. During his celebrated debates in 1858 against Senator Stephen Douglas, he said this was the “real issue” that would grip America long after he and Douglas were gone. Lincoln said of tyranny: “No matter what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it was the same tyrannical principle.”

Lincoln believed that public opinion was central to whom would hold power in a representative democracy and that it was how well a speaker could frame an argument that meant the difference between winning and losing. The secret of Lincoln’s rise to power was his ability to connect to voters through his words. He worked and worked to be understood by the common people. The reporter Noah Brooks told a funny story about the reaction to Lincoln in the 1850s by one ornery Democrat who pounded his cane on the ground as he listened. “He’s a dangerous man, sir! A damned dangerous man,” the Democrat said. “He makes you believe what he says, in spite of yourself!” Lincoln understood the power of language in a system of self-government such as ours. “Our government rests in public opinion. Whoever can change public opinion, can change the government, practically just so much,” Lincoln said. “With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently, he who molds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions.” You can imagine how encouraging that is to someone like me, who works in his day job as an editorial writer and editor!

What was it about Lincoln’s mastery of the English language and particularly his use of the rhythms of the King James Bible that made his inaugural address so timeless? Lincoln did not read widely but he read deeply. He read the King James Bible and the works of William Shakespeare over and over. He particularly loved a line in “Hamlet”: “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends; rough-hew them how we will.” He knew all about rough-hewn wood, of course, but when you think of it, that phrase is pretty much the theme of Second Inaugural Address: that humans might have fought the war, but God shaped its ends. People said he read the Bible as he would a good book. Sometimes when he was feeling miserable about the war, he would slump on a couch and start reading it and found great relief. Aside from any dimension of faith, he found it a fascinating source of wisdom about dealing with problems and what it means to be a human being. I’m sure it was very useful to him as a politician, too, given the intense religious feeling of the voters. The resonance, tone and even language of the Second Inaugural are straight out of the Old Testament: a just God ultimately controls the world, and humans inevitably suffer at times for their errors and sins. The beautiful balancing of “with malice toward none, with charity for all” sounds to me like something from the Psalms or Shakespeare — the most lovely use of the English language you can find anywhere.

Talk about the reaction of prominent listeners to the speech—Frederick Douglass, Walt Whitman, John Wilkes Booth. One of the key themes of the book is Frederick Douglass’s evolving opinion about Lincoln. Well into the war, as a former slave, Douglass considered Lincoln a despicable, conniving, immoral politician who did not care about the fate of African Americans. He had hoped another man would be nominated in 1864, someone like then-Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, who was a much more staunch abolitionist. But in time Douglass came to understand what Lincoln was doing: bringing the public along so that it would support radical changes such as the end of slavery and civil rights for former slaves. Douglass, as a black man, is barred from attending inaugural activities inside the Capitol, so he listens to the speech standing in the mud in front of the platform. He is amazed that here was a president who could express with such power that slavery was an evil so great that it had to be destroyed, even at the cost of the immense suffering in the war. That night, he is determined to shake Lincoln’s hand at a reception at the White House. Again, as a black man, he has a difficult time getting in, but when he does, there is a very moving scene. “Here comes my friend Douglass,” Lincoln says when he sees him in line. Lincoln presses him for his opinion of the speech. “Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort,” Douglass says.

Walt Whitman is covering the inauguration for The New York Times. He treats the event poetically, describing the scene in glowing language. He doesn’t comment on the speech itself. I wonder if he could even hear it. What I’ve always found fascinating was his description of Lincoln after the speech. Lincoln, he wrote, “looked very much worn and tired; the lines, indeed, of vast responsibilities, intricate questions, and demands of life and death, cut deeper than ever upon his dark brown face; yet all the old goodness, tenderness, sadness, and canny shrewdness, underneath the furrows.” Whitman seemed to understand, before almost anyone else, the mythic nature of Lincoln — this prairie lawyer and calculating politician who told dirty jokes — as a great American hero.

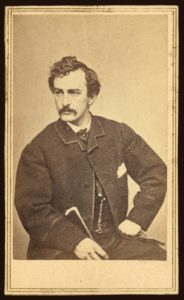

The popular actor John Wilkes Booth stalks Lincoln at the inauguration. He is pulled out of line when he gets close to the president, and many people later believed he would have killed Lincoln that day if he had not been stopped. Booth later told a friend, “What an excellent chance I had to kill the president, if I had wished, on Inauguration Day! I was on the stand, as close to him nearly as I am to you.” His friend asked him what good it would have done to kill Lincoln, Booth answered, “I could live in history.” One of the great ironies of this day is that, as that sun beams down on Lincoln, no one knows he will be dead in six weeks, gunned down by Booth at Ford’s Theatre.

An abbreviated version of this interview appeared in May 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.