Lincoln Prize-winning historian Harold Holzer, recipient of a 2008 National Humanities Medal, former co-chairman of the U. S. Lincoln Bicentennial Commission, co-chair of The Lincoln Forum, and Civil War Times Advisory Board Member, delivered a speech at Gettysburg’s Remembrance Day, November 19, 2017, celebrating the 154th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address and examining current monument issues.

His full remarks were as follows:

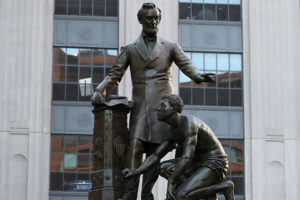

Some three score and seven miles from this spot—in Washington—stands a statue of Abraham Lincoln.

Not that one; another one: Thomas Ball’s statue of Lincoln as a liberator, with one arm clutching the Emancipation Proclamation, the other extended in a blessing, lifting a shackled, half-naked African American from his knees.

It’s unique because it was funded entirely by African American freedmen. Frederick Douglass himself dedicated it. “For the first time in history,” he declared that day, people of color had “unveiled [and] set apart a monument of enduring bronze, in every feature of which the men of after-coming generations may read something of the exalted character and great works of Abraham Lincoln.”

But today, Douglass’s endorsement has been forgotten. The statue is out of fashion—politically incorrect.

To some, the image of Lincoln looming above a kneeling slave is degrading. Critics believe it’s time to take it down and erase it from both the cityscape and popular memory. Despite Douglass’s hopes, it may not long endure, after all.

It is altogether fitting and proper to recall such contested sculpture here and now. We cannot re-consecrate this hallowed ground without acknowledging the statue controversy—the memory crisis—now roiling the country. We gather here above all to remember a great speech on a sacred spot. But Gettysburg is not only a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that the nation might live. It is an outdoor sculpture gallery, too, with more than thirteen hundred monuments: Meade and Lee; Longstreet and Buford; Wadsworth and Warren.

These statues recall a time when valor, more than values, elevated subjects onto pedestals, and when, let’s admit, the real issue that ignited secession and rebellion receded into the shadows; when the Lost Cause was still considered retrievable, and the words that Lincoln echoed here—that all men are created equal—remained a promise unfulfilled.

Now we are engaged in an often uncivil war—a day of reckoning long coming—in which some historians have condemned, civic leaders removed, and activists have defaced, statues. Today, as we remember Lincoln and his finest hour, a speech that went on to inspire statues of its own, we face a challenge to countless other statues and to collective memory itself. Do we embrace it, revise it, or erase it?

That controversial Thomas Ball Lincoln recalls an age when Lincoln held the undisputed title of Great Emancipator.

That was before African-American agency and the U.S. Colored Troops belatedly won recognition by whites as key instruments of black freedom. But does that overdue credit mean that all symbolic, if overzealous, tributes to Lincoln as the sole source of freedom should vanish, including one raised by African Americans themselves? Such a purge could leave our history over-corrected and our landscape barren … and what Lincoln himself called his “greatest act” ignored.

Extremism on both ends of the historic pendulum can distort the arc of memory. Not enough, we must hope, to jeopardize Lincoln — still a hero in an unheroic age.

But enough, I do hope, to make us recognize that the statues of Confederates erected in the South during Jim Crow are sincerely viewed by many as emblems not just of a lost cause, but a bad cause, a treacherous cause, and a racist cause.

Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College, delivers the Keynote Address at the 2017 Dedication Day Ceremony in Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg National Military Park. (Photo by Henry Ballone)

The question is: should they come down? And if so, what happens to the monuments here at Gettysburg, notwithstanding the National Park Service’s recent vow to keep them safe for all time, because there are no forevers in the constant reappraisal of American memory.

Let’s acknowledge one fact: this issue is far from new. Iconoclasm—the desire to destroy effigies—has been a part of the human experience ever since Moses destroyed the golden calf. The ancient Egyptians erased the memory of their only female pharaoh, Hatshepsut, by destroying her statues. Roman emperors obliterated the images of their predecessors.

France tore down its Napoleon statues. And in both Canada and India, independence from the Commonwealth emboldened citizens to topple statues of Queen Victoria. But as good causes won, good art lost.

Nor have Americans been immune to such outbursts. In my own native New York, patriots celebrated the Declaration of Independence by hauling down a giant lead statue of King George III, breaking it to bits, and melting the fragments to make bullets to fight the British.

Lincoln iconoclasm has a history of its own. The U. S. Capitol rotunda boasts its own Lincoln-the-Emancipator statue. Never beloved, officials decided late in the 19th-century to remove it. But in the process, workmen accidentally broke off the Emancipation Proclamation that it holds in its hand.

The workers promptly declared the mission jinxed, and refused to carry it out. Instead of crating Lincoln up, they repaired the scroll and left it where it was. It has stood there ever since.

Yet consider this: on the other side of the world, where the public didn’t have much to say about anything, not even the Russian Revolution could purge the most famous monument in Leningrad: the giant equestrian of Peter the Great.

The Communists simply embraced the legend that as long as that statue stood, the city would stand. Decades later, when the Nazis laid siege, the Soviets padded the bronze czar with sandbags and viewed its survival as the key to their own. It still stands today in the city again known as St. Petersburg.

More recently, when the Taliban blew up the Bamiyan Buddhas, when Isis destroyed the ancient statues at Palmyra, people all over the world lamented these affronts to our shared culture, our common civilization.

Which brings us to New Orleans—Charlottesville—Memphis—Baltimore—and back to New York, where busts of Lee and Jackson have been exiled and statues of Christopher Columbus and Theodore Roosevelt face removal because of how they treated native peoples.

So what should we do about monuments that mark, even celebrate, what the Confederacy fought for, and the Union fought against? Statues do matter, because they compel us to look back, sometimes with pride, sometimes with anger. National ideals matter because they inspire us to look ahead.

But without knowledge and care, emotions often rule—and irreversible decisions can be rushed by recrimination, the “fake news” of cultural re-analysis from a distance.

Still, we must acknowledge together that some statues are now touchstones for racists advocating their survival in the name of white supremacy, and we must summon the courage to condemn that impulse and disavow such rationales. That will give us standing to resist when other monuments, including Lincoln statues, become splatter boards for the red paint of misguided protest.

As some have. Recently, a Native American student organization conducted what it called a “die-in” before a Lincoln statue at the University of Wisconsin.

The group’s spokesman justified the protest this way: “Everyone thinks of Lincoln as the great freer of slaves, but let’s be real. He owned slaves, and…ordered the execution of native men.”

How can we deal with such views? Of course, Lincoln never owned slaves, and did more than any man of his age to end it. Where this myth originated is baffling; that it continues to poison the Internet is regrettable; that it percolates at the college level is nothing less than tragic; and that it informs the statue controversy is frightening.

As for the other charge: yes, Lincoln did authorize the execution of 38 Sioux Indians in Minnesota convicted of rape and murder during the Dakota Uprising. But he pardoned 300 others found guilty only of accompanying the others.

Instead of a die-in at the Lincoln statue, why not a teach-in, or a plaque that explains the Sioux executions in full?

Defiling or dislodging statues reflexively—instead of reflectively—eradicates not only the original impulse for commemoration, but knowledge of the events themselves.

Is memory really worth obliterating—rather than comprehending and, where necessary, countering?

Lincoln once said—not his most elegant phrase though he loved to repeat it: “Broken eggs can never be mended.” Neither can broken statues.

Might we here at least highly resolve to slow the rush to judgment—to consider the genuine benefit of art for art’s sake, and to consider that wonderful alternative: context. Why not explain statues instead of reducing them to dust? Why not add new plaques or computer screens to tell full stories?

All of us should deeply sympathize with the many people sincerely offended by statues of Lee or Jackson, and understandably resentful of having come of age in their shadow. Our Civil War past still haunts us. But obliterating relics cannot change yesterday; learning from them can change tomorrow.

Not all art is meant to fill us with joy. Think of the Arch of Titus in Rome, which glorifies the looting of the Jewish temple in Jerusalem, yet provokes no demands that it be torn down. As art, it deserves preservation; as history, it provokes discussion.

Remember: statues can also be moved to museums, or cemeteries, or parks, or, yes, battlefields.

In the South, if they stay where they are, the fate the Soviets chose for Peter the Great—with new plaques—they should testify to vanished and banished traditions—and not the vile efforts by post-war ideologues to perpetuate white heroes to intimidate black citizens.

But when we blow up memory altogether, and leave no trace of it for our children and theirs, we forget who we were, who we are, and how we can become something even better.

Instead of leaving empty pedestals, why not raise high more monuments? Just as Richmond put up a statue of Arthur Ashe to face the Confederate leaders along Monument Avenue; just as Annapolis treated its disputed statue of Chief Justice Roger Taney, the man who ruled that black men could never be citizens.

They did not tear it down. They raised up a statue of Thurgood Marshall, the first black man to sit on the Supreme Court, a supreme response, if ever there was one, to Taney’s prejudice.

What better way to trace the arc of American history than by pointing first to Taney, and then to Marshall, to comprehend how far we’ve come, even if we still have a long way to go? Without Taney in place, Marshall stands at Annapolis without recognition of what he overcame.

In New York, we just green-lit a new statue of Sojourner Truth—our first. And Central Park, which has 159 statues but only two of women—Alice in Wonderland and Mother Goose—will now get a real woman, Susan B. Anthony to face nearby statues of Lincoln and Douglass.

Some statues are too misguided and offensive to survive. And they are bad artistically in the bargain. I count among these the tribute to the Battle of Liberty Place, the uprising against the mixed-race Reconstruction-era government of Louisiana.

That monument was an outrage, and we should celebrate its removal by the mayor of New Orleans. Frankly, I have no love, either, for statues of Jefferson Davis, unpopular then, irredeemable now.

But these are the exceptions, and I still hope they would not dictate the rule. Context, counter statues, and relocation should always come first.

Let me end with one more proposal, an idea that acknowledges one of Gettysburg’s living heroes, Professor Gabor Boritt. He was born in Budapest, a city that has been occupied, over time, by both Nazis and Communists.

His own family fell victim to both rounds of terror. But even in Budapest, after decades of turmoil, Hungarians refused to destroy the public art once raised to celebrate villains. Instead, they created what they call “Memento Park.”

Here, old statues are arranged in a permanent display that, instead of erasing the painful memories of the past, compels people to confront, comprehend, remember, and above all, learn from them.

Maybe we can be strong enough to do that here: to place the statues of disputed Civil War figures in memento parks of our own.

Lincoln once said, “We cannot escape history. We will be remembered in spite of ourselves.”

He posed for enough sculptors in his lifetime to suggest he profoundly understood the power of images to nourish that history. Let’s not recoil from them. Let’s use them as tools to learn from, and, when necessary, warn against. “Multiply his statues,” Frederick Douglass said in dedicating the Thomas Ball Lincoln, “and let them endure forever.”

Hopefully, we are now strong enough and wise enough, to preserve good art while condemning the bad impulses that inspired some of them.

If not, we might suffer empty squares, empty parks, and, eventually, empty museums too. And maybe empty memories to go with them. Isn’t it better to look than look away?

Let’s take the time we need, so we can be sure, to paraphrase Lincoln, that we are honorable alike in what we give, what we preserve, and what we take away.

Let’s consider that even the most painful parts of our history should not perish from the earth, but long endure to be exposed and confronted.

Rather than defacing or dislodging these statues in anger, let’s consider making some of them teachable instruments that illuminate neglected truths. Rather than take a sledgehammer to the unsettling past, let’s fill in the gaps of our full national story.

We have aside too much hallowed ground to stop remembering, and face too much unfinished work to stop striving to make the last, best hope of earth even better. In that spirit, may old statues inspire new statues, and may the monuments to a divided and divisive past yet become the foundations of a united future.

Thank you.

Harold Holzer is the Jonathan F. Fanton Director for the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College and noted Lincoln expert and author.