Charles A. Dana went wherever he was needed to act as Stanton’s spy

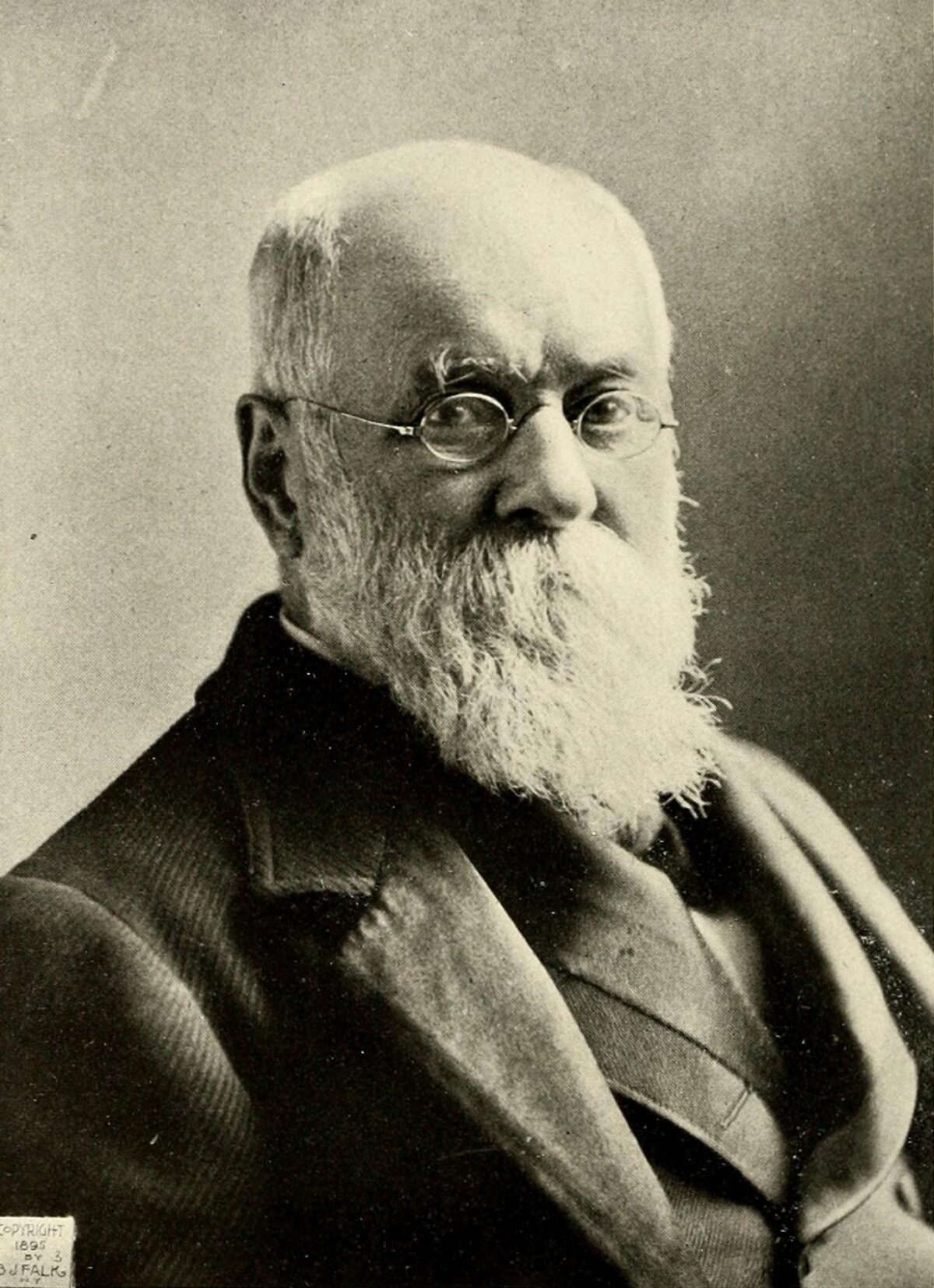

Walt Whitman described Charles A. Dana as “a straight, trim-built, prompt, vigorous man, well-dressed with strong brown hair, beard, and mustache, and a quick, watchful eye. He steps alertly by, watching everybody…a man of rough, strong intellect, tremendous prejudices, firmly relied on, and excellent intentions.” A successful journalist, Dana would have an outsized impact on the Civil War by bringing the qualities ascribed to him by Whitman to further the Union cause, a cause in which he passionately believed.

The only previous full-length biography of Dana was written in 1907. Carl Guarneri remedies this void with an empathetic, but not uncritical, biography of the Civil War’s quintessential “inside man.” In straightforward prose, Guarneri quickly summarizes Dana’s early years, culminating in his job as managing editor of the New York Tribune. Dana would reclaim his place as an outstanding newspaperman after the war as editor of the New York Sun.

After Dana and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton crossed paths, the journalist’s Civil War legacy began to grow. Stanton concluded that Dana was a man on whose judgments he could rely. Dana became Stanton’s troubleshooter, beginning with an assignment to report on questionable contracts being issued by Union quartermasters in Cairo, Ill.

But Dana’s service to the nation took a gigantic step forward when Stanton sent him west in 1862 to “report to me every day on what you see.” Dana’s target was Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, then in the midst of his campaign to capture Vicksburg, Miss., and split the Confederacy. Washington was rife with unfounded rumors of Grant’s military incompetence and his occasional public drunkenness.

Guarneri leads readers through Dana’s undisguised infiltration of Grant’s inner circle. Guarneri maintains, “His dispatches kept Stanton and Lincoln informed about Grant’s movements, explained his plans, and projected confidence in his success.” He probably saved Grant’s career at this critical juncture because “he saw Grant as the fighting general the Union desperately needed, and he committed himself to championing his cause with Stanton and Lincoln.”

After that, Dana showed up wherever the action was hottest. When William Rosecrans got his Army of the Cumberland bottled up in Chattanooga, Tenn., after the Union disaster at Chickamauga in September 1863, Dana’s reports on the situation helped get “Old Rosy” relieved and Maj. Gen. George Thomas put in charge.

When Lincoln and Stanton needed information on the progress of Grant’s Overland Campaign, Dana was ready to ride at a moment’s notice. Guarneri goes so far as to conclude that “Dana called the shots as he saw them without fear or remorse, and his dispatches to Stanton and Lincoln hastened the Union’s day of vindication.”

Guarneri’s insightful analysis and scrupulous research more than justify his conclusion that the Civil War “harnessed [Dana’s] prodigious energy and ambition to the dual cause of preserving the Union and ending slavery.” “Dana’s insider role and his unflinching judgments,” Guarneri maintains, “made him controversial, then and now.”