In “officially neutral” Laos, 3,000 communist troops converged on a handful of Americans at a top-secret 5,800-foot-high mountain base

In February 1968 the headlines out of Southeast Asia were all bad: North Vietnam’s Tet Offensive, the battles of Hue and Quang Tri, the siege of Khe Sanh. In one week, America had suffered its highest casualties of the war. And that wasn’t even the whole story. There was another military disaster in early 1968 that would remain unreported for many years. Nearby in “officially neutral” Laos, 3,000 communist troops converged on a handful of American civilians at a top-secret 5,800-foot-high mountaintop base 15 miles from the North Vietnamese border.

U.S. Air Force Maj. Richard Secord first saw Phou Pha Thi—its name means “Sacred Mountain”—in 1966. “The place was right out of a travel poster,” he recalled. “The crest ran northwest to southeast straight out of a lush valley filled with opium poppies waving scarlet in the breeze.”

U.S. Air Force Maj. Richard Secord first saw Phou Pha Thi—its name means “Sacred Mountain”—in 1966. “The place was right out of a travel poster,” he recalled. “The crest ran northwest to southeast straight out of a lush valley filled with opium poppies waving scarlet in the breeze.”

Several thousand feet below the mountain’s razorback ridge raged an unacknowledged “Secret War,” pitting communist Pathet Lao rebels backed by North Vietnam against the U.S.-supported royal Laotian government, which received assistance from CIA paramilitary advisers, Thai mercenaries and fighters from the Hmong mountain tribes. High overhead American bombers flew routes to and from North Vietnam.

Secord, attached to the CIA, oversaw installation of radar on Phou Pha Thi’s peak to guide those bombers, at night and in all weather, to precise drop points as far away as Hanoi. “To get the best accuracy, the ground station [radar] had to be as close as possible to its targets,” he said.

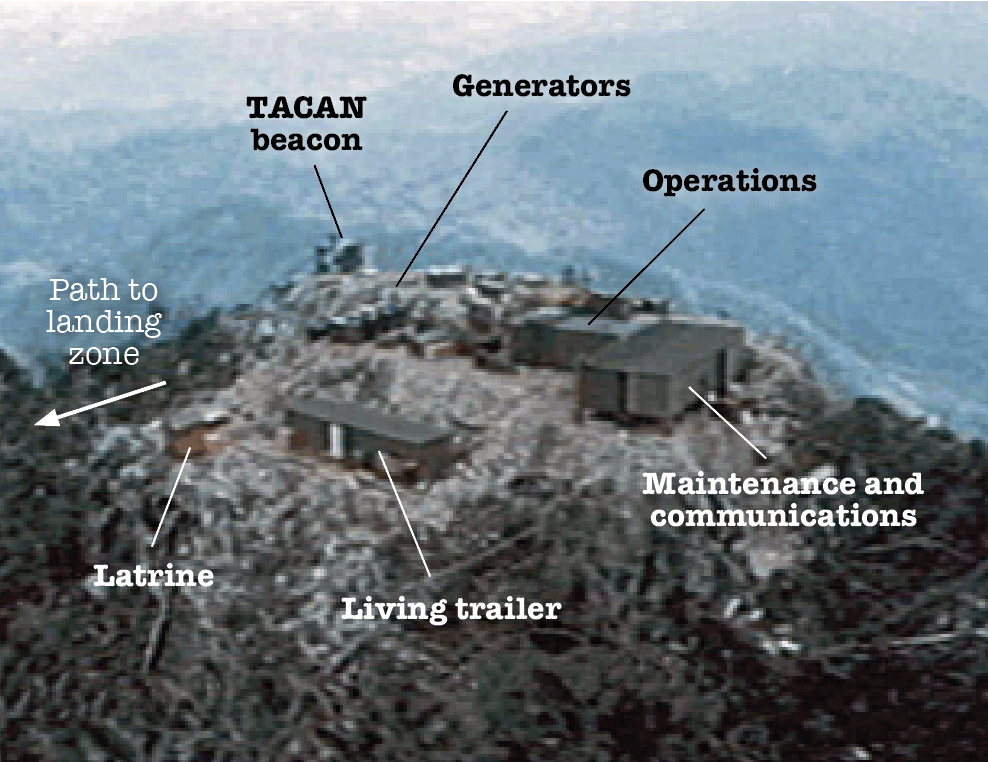

During the Secret War, the CIA dotted Laos with covert bases for Air America, a U.S.-government-owned airline that secretly delivered supplies to the Hmong fighters. Bases with paved airstrips were designated L for Lima (and the initial letter in “Laos”) and those with unimproved airfields as LS, Lima Sierra (the initial letter in “site”). At LS-85 atop Phou Pha Thi, there was no room for a runway at all. The CIA cleared a 700-foot dirt strip on the lower slope to supply the crew of a secret “tactical air navigation” beacon, or TACAN, on the crest.

The U.S. ambassador to Laos, William H. Sullivan, reluctant to further violate supposed Laotian neutrality, forbade American troops to defend the Lima 85 radar site despite an enemy response that was sure to come. On his initial survey of the site in July 1966, 7th Air Force mission coordinator Lt. Col. Robert C. Seitzberg gave its crew “six months if they were lucky.”

Lima 85 eventually received some 150 tons of material. The base and pedestal for the 8-foot radar dish alone weighed a ton. There were power generators and fuel tanks, frequency converters, various tactical radios and antennae, a weather station, a helipad, a command bunker, two 12-by-9-by-40-foot steel containers for living quarters and operations, and a clapboard shack for a latrine. Everything was airlifted in by helicopter. All this construction and activity did not go unnoticed by communist forces around Phou Pha Thi.

“We had intended and planned for a long time to liberate the Pha Thi area,” wrote Maj. Do Chi Ben of the North Vietnamese Army in a 1996 Vietnamese-published book about the raid. “In 1966, in addition to sending a reconnaissance element to prepare the Pha Thi battlefield, [Northwest Military Region headquarters] gave particular attention to developing and training a sapper [commando] team that would practice deep penetration and methods of attacking targets atop karst [limestone] mountains.”

At the end of September 1967 Lima 85 received a handpicked crew officially discharged from the Air Force and re-employed as civilian contractors by Lockheed Aircraft Corp. They were former “U.S. servicemen with critical skills posing as civilian contractors on a volunteer basis,” Secord said. All personnel wore ordinary American street clothes and were issued Lockheed company IDs.

“We felt we were elite,” admitted one of the airmen who switched to Lockheed and thus became ex-Air Force Capt. Stanley J. Sliz, the site day-shift coordinator, “and I still do believe that everybody up there was a special individual. We thought we were going to shorten the war because we could bomb the North during monsoon season.”

On Nov. 1, 1967, the new radar went online. It tracked Air Force F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bombers out of Thailand and B-52 Stratofortress bombers out of Guam, regardless of night or bad weather, computed solutions for ideal bomb release points and relayed the guidance. Over the next few months, Lima 85 would direct 507—about 27 percent—of 1,899 bombing missions over northern Laos and North Vietnam.

Aerial reconnaissance soon revealed the enemy response. “North Vietnamese workers were clearing brush and leveling terrain in an attempt to build a motorable road in the direction of Phou Pha Thi—a dagger aimed at the heart of Site 85,” Secord said. “If it was allowed to get within 15 kilometers [about 10 miles] of the installation by the time the dry season commenced next spring, artillery could be brought up to blast the facility off the map.”

Hmong commander Gen. Vang Pao placed 800 of his men between the road head and the mountain, with 200 more posted on the mountaintop, backed by 300 Thais. As a guerrilla force unable to match the enemy army in strength, the Hmong unit’s job was to detect and delay any attackers only long enough for the Americans up top to destroy the installation and airlift out.

“We had been watching the Song Mai military district in North Vietnam west of Hanoi for months,” Secord said, “waiting for the slowly massing battalions to make their move. We even knew the number of the units and the names of their commanders: two regiments of NVA regulars, about 3,000 troops—one of infantry and one of artillery drawing 85 mm divisional field guns. When it decided to take the field, it would be the largest concentration of heavy artillery observed in Laos since the siege of Dien Bien Phu against the French in 1954.”

On New Year’s Eve 1967, communist forces shelled Lima Site 11, just 5 miles north of 85. Ten days into 1968 the Hmong drove off an enemy probe at the foot of Phou Pha Thi. Two days later Lima 85 was showered with grenades, mortar-shell bombs and rockets launched from a pair of Soviet-made North Vietnamese Antonov An-2 biplanes. Air America Capt. Ted Moore, piloting an inbound helicopter, couldn’t believe his eyes when he saw the biplane: “It looked like World War I.”

Moore, in his faster but unarmed Bell 212 (a civilian UH-1 Huey), chased the Antonovs as his crewman, flight mechanic Glenn Woods, leaned out the side door and fired an AK-47 assault rifle. Both biplanes crashed into the trees short of the border. One was felled by Woods’ rifle.

The other was knocked down by heavy ground fire. This curious little dogfight was the CIA’s first air-to-air victory—and is thought to be the first and only time a helicopter shot down an airplane.

At the end of January 1968, the NVA and Viet Cong began the Tet Offensive, a mass of simultaneous attacks on towns and bases throughout South Vietnam. Although not direct targets of the offensive, the bases in Laos also were in danger.

“We knew that the enemy was coming,” Sliz, the ex-captain, recalled. “We could see them on the other mountains around us. We could see them through binoculars looking back at us.”

Over the first 10 days in March, Lima 85 directed only three bombing raids into North Vietnam but called for 230 within roughly 15 miles of Phou Pha Thi for the base’s own defense. Five more radar technicians were brought in, raising the crew strength to 19 and allowing for 24-hour operations to maintain the bombing runs on North Vietnam and protect the base itself. Yet this barely slowed the enemy road builders’ progress. “We’d knock off a bulldozer or tractor and another would arrive the next day to take its place,” Secord remembered. “Burned-out ‘Cats’ [Caterpillar tractors] littered its shoulder, like locust skins, but the road kept coming.”

Lima 85 could have been evacuated before the NVA reached the base, but military planners decided against it. On March 9, a CIA assessment concluded: “The length of time which seven enemy battalions can be tied down in an assault on Site 85 will significantly affect the enemy’s ability to exercise other aggressive attack options in northeast Laos.” The U.S. military had its hands full with Tet and didn’t need those seven enemy battalions employed elsewhere. Orders came down direct from Washington to hold the site “at whatever cost. It is of vital importance.”

The communists were not planning an all-out assault on Lima 85. “We saw that it would be difficult to use a large attack force and difficult to develop firepower,” admitted Do Chi Ben. “However, if we used a small sapper force and appropriate tactics, it would be possible to achieve success.”

The NVA assault platoon consisted of 40 soldiers from the 41st Special Forces Battalion under the command of 1st Lt. (later Lt. Col.) Truong Muc. All had undergone nine months of specialized training in mountain climbing and scaling cliffs. Late on the afternoon of Sunday, March 10, they took position at the foot of Phou Pha Thi.

At shift change that evening the base commander, ex-Air Force Lt. Col. Clarence F. “Bill” Blanton called a meeting in the operations shack. “He said that we were in dire danger and perhaps we could still get some choppers in that evening to evacuate or we could go ahead and drop bombs and get out at first light,” recalled radar operator and ex-Air Force Staff Sgt. John G. Daniel. “We all decided to stay and continue our mission.”

Daniel felt so secure that he fired up a charcoal grill to cook steaks for everybody. “There was only one way up to the radar and the path was guarded,” he said, but it was a misplaced sense of security. “Just as we were getting ready to break off [from work for the day], this loud explosion occurred outside the door,” Sliz recounted. An enemy shell had landed right on Daniel’s grill. “Steaks were flying everywhere,” he said.

NVA artillery blasted at the mountaintop for an hour and a half. The TACAN beacon, a 105 mm howitzer and the command bunker were hit. The living quarters were riddled with shrapnel. Sliz and his day shift crew took their sleeping bags and M16 rifles and sought shelter elsewhere. Ex-Staff Sgt. Jack C. Starling, a TACAN specialist, remembered, “We took cover on the opposite side of the mountain from where the [enemy artillery] rounds were hitting. Most of them went right over us.”

As night fell a C-130 Hercules flare ship arrived to illuminate the valley for F-4 Phantom II fighter-bombers and A-26 Invader attack aircraft to pound the enemy gun positions. The enemy barrage trailed off, although scattered gunfire could be heard below where the Hmong ground force was engaged. No Americans were wounded, and the radar was undamaged. Blanton and his night shift went to work calling in airstrikes, but Sullivan in the Laotian capital of Vientiane made the decision to evacuate at first light. Secord and his CIA cohorts in Thailand spent the night arranging air cover for the pullout.

Meanwhile, Muc and his NVA assault platoon did what the Americans all thought impossible—climbing Phou Pha Thi in darkness. By 3 a.m. they were on top of the ridge and positioned to assault the helipad, the communications shed and radar. The North Vietnamese planned to attack at dawn, but squad leader Trinh Xuan Phong’s cell bumped into a concealed Thai guard post at about 3:45 a.m.

“All of a sudden, we started hearing machine gun fire and hollering from the Vietnamese,” Starling remembered. “It looked to me like there were probably a couple hundred of them out there and no Thai Army. Now I was scared.”

The attackers immediately fired rocket-propelled grenade launchers (B40 Vietnamese-made Russian RPG-2 launchers) into the generators and radar center. Blanton and his crew ran outside and came face to face with the attackers. As generator repairman and ex-Staff Sgt. Bill Husband later told Sliz: “Blanton said, ‘Hey, wait a minute!’ and reached for his wallet so he could show these guys his Lockheed service ID and that’s when they shot him.”

The enemy was already overrunning the helipad and cutting off the only path down the mountain. There was no way out. Sliz, Daniel and a few others knew a hiding spot. “We sneaked down the mountain about 20 feet to a cave,” Sliz said. The cave basically was just a rock overhang on a ledge with a sheer drop to the valley floor. “There were five of us in that little hole, with barely enough room for two. It wasn’t the greatest spot.”

Above them NVA commandos were already mopping-up. Starling and ex- Staff Sgt. Willis R. Hall, a cryptographic technician, took cover in the jumble of rocks on the summit. Starling returned fire with an M16 until it jammed.

“Me and another guy [Hall] were laying side by side,” he said, “and these two Vietnamese came down on where we were and jumped over him and landed on my ankle. I had been hit earlier by sniper fire, in the leg. When they jumped over him, they turned around and just opened up on him. How they missed me I’ll never know.” Starling saw the enemy finish off Blanton and his men and begin looting the bodies. He played dead. “At that point I figured I was dead.”

Down on the rock ledge, Sliz’s crew chief, ex-Chief Master Sgt. Richard “Dick” Etchberger, prepared to make a last stand. “Etch was watching the trail above,” Sliz remembered, “and whispered, ‘Stan, there’s people coming!’ I said, ‘When they get close enough, shoot.’ So he did. Almost immediately all hell broke loose. They opened up on us from all over, throwing grenades and firing their AK-47s.”

Ex-Staff Sgt. Henry G. Gish and ex-Tech. Sgt. Donald K. “Monk” Springsteadah were killed almost immediately. Sliz and Daniel were both wounded. At one point a grenade bounced onto their ledge. They only survived by rolling Gish’s body onto it. Sliz said, “When I came to, pieces of Hank were all over me. But the rest of us weren’t killed.”

At the command bunker near the helipad, CIA case officer Howard Freeman, an ex-Special Forces noncommissioned officer who had arrived at the site the Friday before, ventured out with a shotgun and a handful of Hmong to reconnoiter the summit, which was wreathed with smoke from the burning generators. Freeman nearly walked into an NVA commando coming the other way around the operations shack. A hair-raising, cat-and-mouse firefight ensued at point-blank range in the little arena on top of Phou Pha Thi. One Hmong was wounded. The rest fled with him.

Alone, Freeman surprised a pair of NVA soldiers in a machine gun nest and shot them both in the back. He was hit in the leg and withdrew under the smoke of a white phosphorus grenade. Seeing no survivors, Freeman made his way back to the bunker and told ex-Sgt. Roger Huffman, who was in contact with the support aircraft, to call down an airstrike on the site.

On the ledge Etchberger was the only man unhurt, returning fire with his M16. “Dick never got hit during this time and was directing me on what was taking place and what to do,” recalled Daniel, who used their only radio to raise a pair of inbound A-1E Skyraider fighter-bombers. “Dick and I decided that we needed them to drop their ordnance on top of the hill as there was no evidence of life there, except for the ones shooting at us.”

Sliz told them he agreed with that decision. “We’re goners anyhow, so you might as well do it.”

The Skyraiders swooped in to dump full loads of cluster bombs, scattering hundreds of tennis-ball-sized grenades over the mountaintop. “It was like setting off a string of firecrackers, only a thousand times magnified,” Sliz said. “It was a horrendous noise. After a while everything was deathly still. I thought I had gone deaf after the A-1’s dropped their bombs. I couldn’t hear a thing, just the ringing in my ears.”

As the smoke drifted off and the dust settled, rescue choppers moved in to pick up anybody still alive. A Huey hovered over the rock ledge and lowered a hoist. Etchberger helped Sliz and Daniel onto it. When Husband, with shrapnel wounds up and down his left side, limped past for the chopper, Starling—unable to walk—called out: “Tell them I’m here!”

Together, Husband and Etchberger were last up the line, tumbling aboard the Huey just as it began taking groundfire. Etchberger, who so far had come through unscathed, had just grabbed a seat when he was struck by a bullet coming up through the bottom of the helicopter. He died en route to Thailand. More Hueys set down at the helipad to pick up Freeman, Huffman, CIA officer Bill Spence and several wounded Hmong. Husband told everyone that Starling was still on the mountaintop.

Starling was plucked off Phou Pha Thi by chopper at about 9:45 a.m. “It seemed like 20 hours,” he recalled, “but it was only five or six hours. I just stayed there and kept still because I didn’t have anything to protect myself with.”

He was the last of the seven American survivors pulled to safety.

The 12 men left behind were presumed dead—the largest single-day loss for Air Force ground operations in the Vietnam War. One more, Skyraider pilot Maj. Donald E. Westbrook, was shot down and killed during efforts to bomb and destroy the remaining facilities at Lima 85. The communists claimed that they had killed 42 men, including Hmong and Thai defenders. They reported that only one of their 3,000 men had been killed, with two others slightly wounded.

Phou Pha Thi was never retaken. On March 31, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced a partial halt to the bombing of North Vietnam and in November called it off entirely.

The Americans lost at Lima 85 were all awarded posthumous Bronze Stars. Freeman, who survived, received the CIA’s Intelligence Star, the agency’s third-highest award. For his selfless actions to save his teammates, Etchberger was posthumously awarded the Air Force Cross and ultimately the Medal of Honor, presented in 2010 after the battle at Lima 85 finally was acknowledged by the U.S. government.

In 2005 the remains of several American bodies were recovered where the enemy had thrown them—on a ledge 540 feet below the summit. The fate of the rest has been the subject of rumors, government denials, freedom-of-information searches and lawsuits ever since.

“The disaster at Phou Pha Thi is a shocking story,” Secord said, “a bitter pill that was tough enough for me to swallow at the time. It gets no sweeter in the telling. Still, it’s a story that must be told, if only to let those who paid the final price rest a little easier.” V

Don Hollway wrote “Flaming Flattops” in the August 2020 issue. He lives in central Pennsylvania.

For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: