“Let me win your heart and mind or I’ll burn your God damn hut down.” Those are the words inscribed on the small, slightly beat-up silver Zippo cigarette lighter that sits on my desk. On the reverse is inscribed: “Vietnam, 67-68, Qui Nhon,” the time and place where I served. Below that is a pint-sized image of the pointy-nosed spy-versus-spy guy from the Mad magazine comic.

I can’t remember just how and when I came into possession of that lighter. It’s been 43 years, and my memory is hazy. Its provenance aside, the fact that this wartime object keeps me company today is a small illustration of the iconic place that Zippo lighters have in the lives of those of us who took part in the American war in Vietnam—even those of us who don’t smoke.

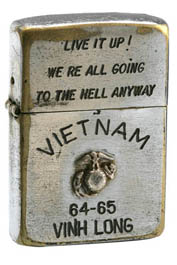

The fact is that Zippos are much more than simple metal cigarette lighters. The ubiquitous Zippo, engraved in-country, became woven into the fabric of the Vietnam War experience. These compact lighters “are the small, speaking, archeological objects that bear witness to great personal heroism, pride, pain and tragedy,” wrote Jim Fiorella in his photo-filled 1998 coffee-table book, The Viet Nam Zippo, 1933-1975. The lighters served as “amulets and talismans bringing the keeper invulnerability, good luck and protection against evil,” Sherry Buchanan penned in the excellent 2007 Vietnam Zippos, which examines the extensive Vietnam War Zippo collection put together by Bradford Edwards.

The humble Zippo was born in 1932, when George G. Blaisdell, whose Pennsylvania oil business was foundering as the Great Depression put a chokehold on the world economy, designed a small silver-colored rectangular cigarette lighter with a hinged top. He coined a modern-sounding name for his innovative design, the “Zippo,” playing on the word “zipper,” and began selling the lighters for $1.95 in 1933. A few years later the Zippo Manufacturing Company began engraving words and images on its lighters, primarily as marketing tools for other businesses.

The company hit the big time in World War II when—like many other American manufacturers—it stopped making consumer items and produced its lighters for the U.S. military. From 1943 to 1945, every Zippo made was shipped directly to post exchanges and Navy ships around the world. Millions of Zippos were carried into battle by American troops across the globe. They were a huge hit—an essential tool in the days when a high percentage of Americans, especially young men, saw smoking as a harmless and satisfying recreation—one that advertisements often even touted as having healthful benefits. Indeed, cigarettes were distributed to the troops by the Red Cross.

“If I were to tell you how much these Zippos are coveted at the front and the gratitude and delight with which the boys receive them, you would probably accuse me of exaggeration,” the famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote in August 1944. “I truly believe that the Zippo lighter is the most coveted thing in the army.”

To date, Zippo has produced nearly a half-billion cigarette lighters.

The engraved Zippo played a unique role in the Vietnam War. Aside from the fact that GIs by the hundreds of thousands bought them at PXs and on the black market, the term “Zippo” worked its way into the war’s military lexicon wherever fire and flame were concerned. Burning down a hooch or a village, for example, was widely known as a “Zippo job,” a “Zippo mission” or a “Zippo raid.” Grunts who specialized in performing these fiery missions sometimes were called “Zippo squads.”

The Army’s Vietnam War flame-throwing M-67 tanks and M-132 armored personnel carriers were commonly called “Zippos” or “Zippo tracks.” And, guess what the troops used to ignite the APCs’ napalm fuel when the electrical igniters wouldn’t work? No surprise also that the M2A1-7 portable flamethrower used in Vietnam was referred to as a “Zippo.” A “Zippo monitor” was one nickname for a Brown Water Navy boat that was equipped with a flamethrower.

In fact, some people referred to the whole American operation in Vietnam as the “Zippo War,” branding the entire effort with Zippo-lit village-burnings.

As for the other side, history does not record how many North Vietnam Army troops and Viet Cong fighters carried engraved American-made Zippos, but it’s a good bet that many of them did. And while the enemy didn’t have flamethrowers, they did use Zippos as a weapon—booby-trapping them and depositing the lighters in bars and other rear areas for unsuspecting Americans to pick up and detonate.

More than half of American men 18 and over smoked in 1965, and about 44 percent did in 1970, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Extrapolating those statistics to the war zone—and taking into consideration that smoking always has been big among troops in a war—a good guess would be that well over a million men (and women) who served in the Vietnam War smoked while they were in-country.

While other types and brands of cigarette lighters were available, the lighter of choice in Vietnam was, by far, the Zippo. It’s a good guess that American troops bought several hundred thousand—probably as many as half a million—Zippos in Vietnam.

We used them, naturally enough, to light up, as well as to put fire to heat tabs or pieces of C4 plastic explosives to cook our C rations and pop our TV Time popcorn. They also served as a tiny mirror for shaving in the bush, or as repositories for salt tablets in the lighters’ bottoms to replenish on a sultry day in the boonies. We carried them most often in our fatigue chest pockets or tucked them into the camouflage band on our helmets.

Enterprising Vietnamese entrepreneurs popped up around base camps setting up shop to engrave our PX-bought Zippos with whatever words or pictures we could dream up. Some creative guys engraved their own, too, as they whiled away the hours in the field or in the rear.

The most common engravings were maps of Vietnam, unit insignias, places and dates, peace signs, cartoon characters (the irreverent beagle Snoopy from Charles Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip was big) and nude women—a lot of nude women. The most common phrases included the ubiquitous FIGMO (“Fuck it. Got my orders,” meaning your tour was up); variants of “Yea, though I walk through the valley of death…” from the 23rd Psalm; and “Death is our Business and Business is good.” The Zig-Zag man, who adorned papers used to roll your own cigarettes—as well as joints—was also a popular adornment, along with other phrases and illustrations regarding marijuana.

The Zippo makers also churned out their own factory-engraved lighters that were specially designed to appeal to the troops in Vietnam. That included lighters featuring finely wrought images of all five service logos, and—perhaps because sailors were particularly big-time smokers back then—lots of Brown Water Navy boats.

In the decades since the end of the Vietnam War, thousands of people—veterans, military memorabilia collectors and just-plain-old Zippo fans—have put together personal Zippo lighter collections. Unfortunately for collectors, fake Vietnam War–engraved Zippos, also known as counterfeits, have flooded the market. Counterfeiters have been cranking them out in Vietnam for years, and you can pick up a phony wartime Zippo there for a few bucks. The most obvious fake is a generic lighter and insert on which someone has engraved the Zippo logo.

The Vietnam War tradition of engraved Zippos lives on in legitimate forms, too. In 1998 the Zippo company produced the “Vietnam Collectors Set,” lighters adorned with miniature images of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in black matte. The words “Vietnam, 1965-1972” are etched on the lid (even though the names on The Wall are from 1959-1975). Zippo limited production of the Vietnam Collectors Set to 5,000. I just saw one listed on eBay for $39.99.

Journalist, historian and author Marc Leepson is the editor of Webster’s New World Dictionary of the Vietnam War, and is senior writer and columnist for The VVA Veteran magazine.

Click here to view more Zippo art.