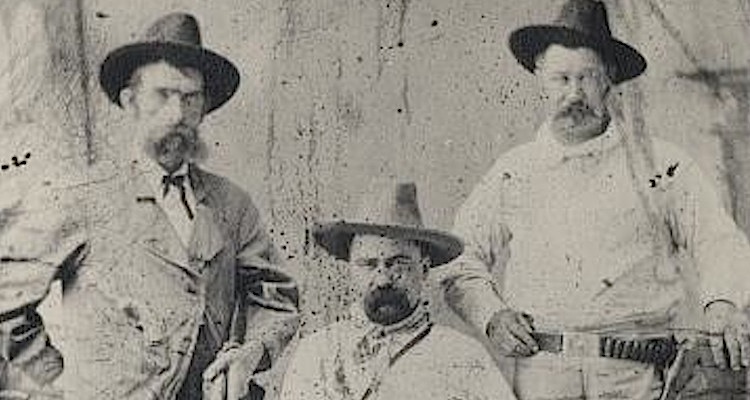

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency, established in Chicago by Allan Pinkerton in 1850, chose as its logo an unblinking eye over the motto “We Never Sleep.” Well, the company remains alert. Now headquartered in Ann Arbor, Mich., Pinkerton provides a wide range of corporate risk-management services and uses a stylized eye logo similar to the ever-watchful CBS eye. Wells Fargo, a multinational company whose roots go back to the 1852 formation of California-based Wells, Fargo & Co., is often associated with the West (its logo is a stagecoach), while Pinkerton has ties to the Midwest (where the “Pinks” were known to bust heads to bust strikes). But Pinkerton also has strong connections to the East (where it provided security for President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War) and the Wild West (where it sought to apprehend infamous outlaws). The Pinkertons relentlessly pursued the James-Younger Gang and later the Wild Bunch. The Pinkerton men might never have slept, but neither did the badmen, who for the most part used cunning, experience, familiarity with their environs and support from family and friends to frustrate the wide-eyed pursuers.

After the Civil War, about the time Frank and Jesse James and Cole Younger were making the transition from Southern guerrillas to Missouri bank robbers, the Pinkertons successfully pursued an Indiana gang. In that state’s Jackson County on Oct. 6, 1866, the Reno brothers pulled off what arguably was the first U.S. peacetime train robbery, nearly seven years before the James-Younger Gang robbed its first train. Other Reno train robberies followed that first one, but dogged Pinkerton agents infiltrated and brought down the gang (read “Reno Gang’s Reign of Terror,” by William Bell). In June 1871, as detailed in Ron Soodalter’s “Allan Pinkerton: ‘They Must Die’” (in the August 2015 issue), son Robert was the first of his family to pursue the James boys, but he came home to Chicago empty-handed. In early 1874 Allan himself became professionally involved, at the request of the Adams Express Co., after the bold ex-guerrillas robbed a train at Gads Hill, Mo. “Given Allan Pinkerton’s roster of high-profile cases, there was no reason to assume he wouldn’t succeed,” writes Soodalter. Rounding up the Renos, however, hadn’t prepared Pinkerton and his agents for what lay in store in Missouri.

First Frank and Jesse James murdered agent Joseph Whicher, and a few days later Jim and John Younger shot down agent Louis Lull (who killed John for his trouble) and a local lawman hired as a guide. Devastated but determined, Allan Pinkerton arranged for his agents to capture the James boys at their family farm, but the explosive event there on Jan. 25, 1875, was deemed an unwarranted attack and certainly was a public relations nightmare for the agency. Pinkerton remained on the hunt, but only dead ends followed. The disastrous Northfield Raid landed the three surviving Youngers in a Minnesota prison in 1876 and a notorious coward assassinated Jesse James in April 1882, but the Pinkertons didn’t have a hand in either of those events or in Frank James’ subsequent surrender.