The audacious hijacking of Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305 on November 24, 1971, degenerated into a frustrating quest for the FBI while remaining a fascinating “who done it” for the rest of us. Still unsolved after five decades, this aviation mystery evolved from a short list of solid facts into an urban legend bearing a thick overlay of conjecture. A new and novel form of grand larceny in the tradition of Bonnie and Clyde seemed to have been created. Maybe a “little guy” had actually beaten the system?

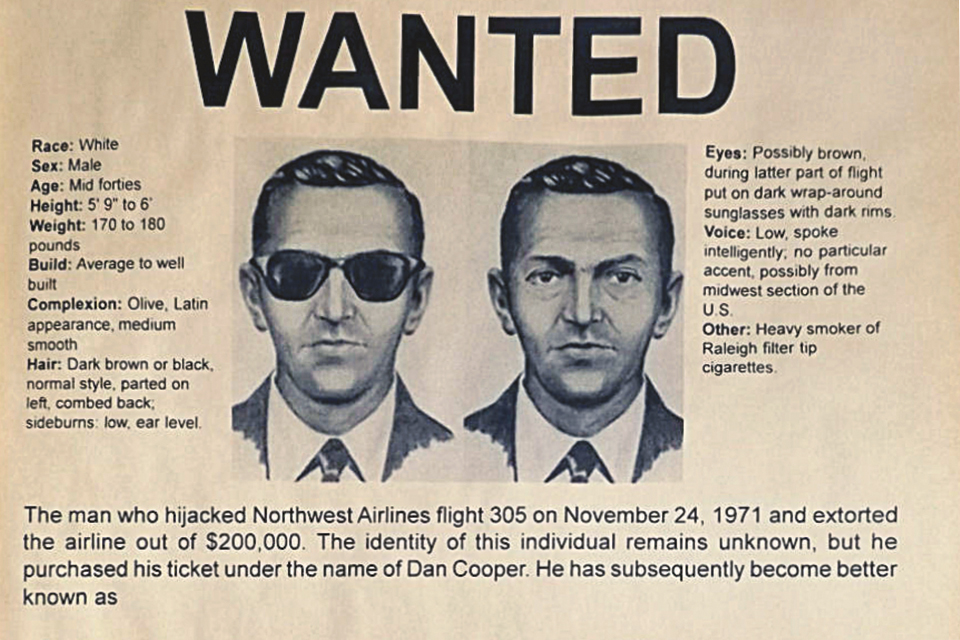

A nondescript olive-skinned man carrying a black briefcase and traveling alone under the ticketed name of Dan Cooper boarded the 727 at 3 p.m. for the short hop from Portland to Seattle. The passenger load of 36 Thanksgiving travelers was unusually light for a pre-holiday afternoon. With the declaration of open seating, Cooper settled himself into seat 18E in the very last row and then purchased with cash a bourbon and soda while chain-smoking Raleigh filtered cigarettes. Not long after takeoff he handed a note to the nearest flight attendant that said, in neatly drawn capital letters: “I HAVE A BOMB IN MY BRIEFCASE. I WILL USE IT IF NECESSARY. I WANT YOU TO SIT NEXT TO ME. YOU ARE BEING HIJACKED.” When the attendant put the note, unread, into her pocket, Cooper said, “Miss, you’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.”

After the 727 landed in Seattle, Cooper’s demands for refueling, $200,000 in cash and four parachutes were met. His clean-cut appearance, rational demeanor and technical knowledge were all indicators of a bright, normal person. The 35 other passengers, plus two of the three flight attendants, were released in Seattle and interviewed by the FBI. Some estimated the hijacker’s age at about 45. Bill Mitchell, a college student seated in 15A, reported seeing thermal long underwear extending into the gap between Cooper’s pant cuffs and the loafers he wore.

The remaining crew of four was instructed to fly through the inky darkness destined for Mexico City at 10,000 feet, unpressurized, with flaps and landing gear extended. This high-drag configuration rapidly consumed a full load of jet fuel, requiring a refueling stop in Reno, Nev., shortly after 11. There it was confirmed that Cooper, the ransom, the bomb and a parachute were gone.

A worldwide phenomena at the time, hijackings typically ran their course and were forgotten. The first airliner hijacked to Cuba was in 1961. The pace quickened to three per month during the summer of 1969. Perpetrators ranged from the mentally unbalanced to political dissidents avenging a genuine (or contrived) grievance. U.S. airlines generally obliged the demands of the hijacker because passengers, aircrews and airframes most often survived. That precedent abruptly ended with the devastating terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001—an epic event that triggered creation of the Transportation Security Administration, intense airport passenger screening, fortified cockpit doors and vigilant passenger identification.

As authorities initially investigated a suspect named D.B. Cooper who was quickly cleared of involvement, that name erroneously slipped into one of the first press accounts and became immortalized. Attracted to the Reno airport by broadcast news accounts, gawkers lined the chain link fence, staring at the wayward airliner parked with its aft ventral stairway extended. FBI agents went to work, dusting for fingerprints and searching for other forensic evidence. Without DNA testing (not yet invented), an ashtray full of cigarette butts was lost. (DNA tests were later conducted on a sample from a tie that Cooper had left on the 727, but proved inconclusive.) Cooper was aboard the airliner for five hours, chatting freely with cabin attendants, yet shared no useful clues about his identity. Handwriting analysts were stymied because Cooper reclaimed his handwritten notes before bailout.

Already the D.B. Cooper mystique was evolving into a cultural phenomenon. Few criminals become heroic, but Cooper had touched a nerve. The story was rife with gaps and inconsistencies, inviting speculation. The result is enough books to fill a grocery store shopping cart.

Brief glances into the briefcase convinced the crew that the bomb was real. The demand for a flight attendant to sit next to Cooper bestowed three important benefits during the layover in Seattle: The interphone provided instant communication directly with the captain; close proximity discouraged intervention by a law enforcement sharpshooter; and, most important, her safety was the stated reason the cockpit crew remained with the airplane.

Cooper demonstrated an understanding of airport operations. Furthermore, he had an insider’s knowledge of aviation. When asked the desired flap setting, he instantly responded “15 degrees.”

The Port of Seattle, FBI and the airline acceded to Cooper’s every whim—a strategy endorsed by Northwest Orient’s president, Donald Nyrop. Despite some delays, nothing requested was denied; however, rounding up cash and parachutes late in the afternoon on Thanksgiving eve was a challenge. Fortunately a hoard of circulated $20 bills existed in a safe at Seattle First National Bank (Seafirst) as a kidnapping contingency ransom fund. Best of all, the serial numbers were already recorded. Each bundle, holding $2,000, was secured by a rubber band. The cache of $200,000 weighed 21 pounds. Attempts to obtain parachutes from nearby McChord Air Force Base failed. Earl Cossey, a local FAA-certified parachute packer, provided two backpack-style military parachutes via Linn Emrich’s sport jumping business, which also supplied two chest-style chutes.

Exceptionally polite, Cooper became agitated and invoked profanity only once. That was when the refueling in Seattle went awry, possibly at the behest of the FBI, though it was blamed on vapor lock. A step truck was positioned at the left front cabin door. With the arrival of cash and parachutes, Cooper ordered the other hostages to deplane. The sole remaining flight attendant, Tina Mucklow, a deeply religious 22-year-old, scurried up and down the step truck stairway five times, each time delivering a parcel to Cooper.

Cooper first inventoried the loot before focusing on the parachutes. A military emergency parachute consists of a canopy made of ripstop nylon, 28 feet in diameter, secured to the harness by risers. With surgical precision, Cooper quickly went to work on one of the chest-style sport parachutes by opening it and using his pocketknife to harvest six-foot riser segments.

Confronted with a choice of a superior performing sport chute, Cooper instead opted for a military backpack-style parachute and began his own inspection by pulling the record booklet from its pocket. Satisfied, he deftly donned the chute. Mucklow was impressed with how quickly he adjusted the chest and leg straps. The purloined riser cords were used to wrap a packet of cash and then secure it to his waist so that the improvised rucksack would impact the ground first—another hallmark of military training.

After daylight gave way to darkness, a radio call went out: “Tower, Northwest 305 is ready for taxi.” As is typical for late November, a fierce storm off the nearby Pacific Ocean pummeled western Washington that night.

Huddled in the cockpit, Captain William Scott was in constant radio contact with both air traffic controllers and company headquarters in Minneapolis. Cooper was not privy to this dialog, but it probably distracted copilot William Rataczak. It was his turn to fly this segment. Victor 23 is the imaginary pathway in the sky plied by airliners between the busy Seattle (SEA) and Portland (PDX) airports. Rather than the normal steep climb into the serene atmosphere above, Rataczak disengaged the autopilot and hand-flew the big Boeing tri-jet southward through the low-hanging storm clouds, intermittent precipitation and constant crosswinds gusting to 45 mph.

Shortly after takeoff, Cooper ordered Mucklow to extinguish the cabin lights, close the first-class curtain, go to the cockpit and stay there. The two exchanged a final friendly wave as she pulled the first-class curtain shut. Cooper was never seen again. Indicator lights in the cockpit signaled when the aft door and ventral stairway were unlatched. At 8:12 p.m., the crew sensed a subtle airframe shudder accompanied by a change in cabin pressure, suggesting Cooper had jumped.

With the war in Southeast Asia winding down, I arrived at McChord AFB, between Seattle and Portland, in 1973 as an aircrew life support specialist. A friend organized a weekend hunting excursion in late 1974. After a day in the rugged terrain, the topic of Cooper’s hijacking came up as we sat in the chilly darkness around the crackling evening campfire. An Air Force Convair F-106 interceptor pilot told his story. He recalled the 318th Fighter Interceptor Squadron had stood down for an annual bash on that fateful night three years earlier. As part of NORAD (North American Air Defense Command), the normal mission of the squadron was defending the ADIZ (air defense identification zone), a boundary line over the nearby Pacific. Four of the Mach 2.2 interceptors were always on alert, ready for immediate takeoff.

During the party, pilots from another base, who were unfamiliar with the local terrain, performed alert duty. A call came in: “Hijacking in progress—scramble—this is not a drill!” Two of the missile-laden fighters belched afterburner flame as they clawed for altitude in pursuit of Cooper’s 727. Controllers barked intercept coordinates over a secure radio net. The F-106s, however, were designed for supersonic dash. As then configured, the airliner was too slow for them to follow without slewing back and forth to maintain sufficient airspeed.

The inbound airliner with a potential jumper and chase aircraft in hot pursuit motivated air traffic controllers to clear a broad pathway over greater Portland. Although the F-106s caught up with the airliner, they were unable to see anything in the darkness and were recalled just prior to entering PDX airspace.

Write us!

Have something to say? Send us an email or Letter to the Editor at aviationhistory@historynet.com. Please include your name and hometown.

The 727 passed close to PDX but its exact trajectory was unclear. With copilot Bill Rataczak manhandling the controls while battling crosswinds, was Flight 305 centered on Victor 23? Or to the west, nearer the Columbia River? Or east, upwind of the Washougal River watershed? Bar patrons in the small town of Ariel clearly heard an airliner pass overhead. Or was it the sound of fighter jets disengaging from a futile chase?

The need for an eyewitness to Cooper’s jump was dire. Did the parachute open high or low? The temperature at 10,000 feet was 22 degrees and it was windy. If Cooper’s parachute opened at high altitude, surely the gusting winds would have blown him far inland and into very rugged country. Did the canopy “stream” (malfunction by tangling) or fail to open?

The Air Force pilots who had pursued Cooper were much better prepared than he was to survive such a jump. The temperate rainforest of the Cascade foothills is tightly packed with Douglas fir and other conifers commonly growing to 250 feet. Because of the jungle war in Vietnam, the newest military chutes were equipped with a tree lowering device built into the back pad, enabling safe descent from tall trees. Also attached to the parachute by lanyard was a survival kit packed with useful items: a handheld radio, one-man life raft, gloves and wool stocking cap, matches, compass and signaling devices. Even on land, the life raft provided shelter and insulation from the cold. Tightly laced leather jump boots were mandatory for ankle support on landing. Cooper had none of these items.

Was D.B. Cooper a dashing and brilliant hero or a desperate loner stumbling toward suicide? Evidently he was an eclectic mixture of both. Despite demonstrating knowledge of both airfield operations and parachutes, his other choices were fatally flawed. Hikers, hunters and other nature lovers routinely get lost in the Pacific Northwest mountains and are never seen again. Late November in the region is characterized by short days, persistent precipitation and temperatures near freezing.

Upon landing, Cooper would have needed to quickly seek shelter. Cocooning within the parachute canopy would provide a modicum of protection, but the worst problem was the loafers. Surely they would have been lost in the windblast of bailout. Bare feet, hands and head invite hypothermia and make travel by foot difficult on slippery rocks within steep ravines blocked by fallen trees.

Extensive air and ground searches yielded nothing. Two hundred U.S. Army soldiers from Fort Lewis (accompanied by 20 FBI agents) scouring the rugged terrain on the south shore of Lake Merwin in March 1972 found two unrelated bodies: a deceased woman in a mill pond and the remains of a man with a broken leg who had starved to death.

In 1971 only the Boeing 727 and Douglas DC-9 had aft ventral stairways. Copycats emerged who survived their jumps but got caught. What could be done? The mechanical solution was simple but ingenious, visible to all but never heralded. The mechanism consisted of a paddle measuring about four inches in diameter, a spring and a plate. On the ground, the spring pushed the paddle outward and allowed the ventral stair to lower. In flight, the slipstream pushed the paddle back 90 degrees, blocking the door from opening. Every 727 and DC-9 either received a “Cooper vane” or had the door permanently sealed.

Years passed without a useful clue until February 10, 1980, when eight-year-old Brian Ingram, on a family picnic, dug into the sandy spit on the north shore of the Columbia River downstream from its confluence with the Washougal River. Young Brian excitedly brought to his parents a stack of waterlogged $20 bills with an aggregate value of $5,800. The two soggy bundles were secured with their original rubber bands, now rotted. The third was a partial bundle. All the bills were in the same order as recorded by Seafirst bank almost a decade earlier. Together, the excited family proceeded to the Portland FBI office. Interest in D.B. Cooper exploded in the wake of this stunning discovery.

Neither the Columbia River nor the Washougal watershed had been previously searched. Did the Columbia’s relentless current sweep Cooper’s drowned body and parachute 100 miles downstream and into the Pacific at Astoria? Were the bundles of cash buried in the river bottom? Did river dredging conducted in 1974 disturb the cash by lifting a stack of it onto the spit?

Larry Carr was the last FBI agent assigned to the case and contributed to an updated profile of Cooper published in March 2009. Carr surmised that Cooper had served with the USAF in Europe as an airborne cargo handler (possibly a loadmaster). In that role, he would have been familiar with the best flap settings for airdrop. Also, he would have often donned a parachute—but never actually jumped.

Carr thinks it’s highly unlikely that Cooper survived the jump. If his job required him to throw cargo out of planes, Cooper would have worn an emergency parachute in case he fell out. That would have provided him with working knowledge of parachutes but not necessarily the functional knowledge to survive the jump he made. Carr further theorized that Cooper may have taken an aviation job in Seattle when he got out of the military and it’s possible he lost his job during the industry’s economic downturn in 1970-71. If he was a loner with little or no family, Carr said, “Nobody would have missed him” after he was gone.

The FBI ceased investigating America’s only unsolved airliner hijacking in 2016. No additional loot was ever recovered and generous cash rewards went unclaimed despite the publication of every serial number. Agent Carr’s conclusion is logical. In all likelihood the mystery man known as D.B. Cooper was killed in his jump and his body rotted away, either on land or underwater.

John Fredrickson is the author of five aviation history books, including the recently released (with coauthor John Andrew) Boeing Metamorphosis: Launching the 737 and 747, 1965–1969. For further reading, Fredrickson notes that a recent trip to his public library turned up a stack of 16 books on the Cooper hijacking—take your pick.