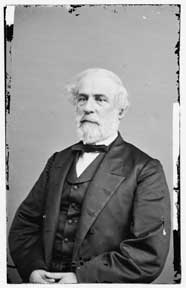

Unwritten History: Why didn’t Robert E. Lee write his memoirs?

Just two months after Appomattox Court House, Robert E. Lee received a letter from a wartime acquaintance that either planted a seed in his mind or affirmed a project he was already seriously considering. It was now Lee’s duty, urged ex-Confederate agent Beverley Tucker, writing from Canada, to “give to the world and posterity, a faithful history of the causes of the late terrible conflict, and the manner in which the war was conducted on either side.” Lee never completed such a work. Yet for more than a year it was the No. 1 item on his personal “to do” list. And in the course of that year and the four remaining to him, he left a variety of tantalizing hints about what he would have said if he had in fact put pen to paper.

Likely in the same month as Tucker’s letter (July 1865), Lee met with Charles B. Richardson, representing New York’s University Publishing Company. While Tucker wanted Lee to produce a wide-ranging book on all aspects of the rebellion, Richardson was seeking a more focused military study of the conflict. Even that was too broad for Lee’s interests. He counterproposed a history of the Army of Northern Virginia’s campaigns, if only he could obtain subordinates’ reports and other papers not then available to him. The publisher eagerly agreed and promised to help track down the material.

Lee promptly began gathering primary sources. In late July he started sending form letters to some of his former officers. Many began: “I am desirous that the bravery and devotion of the army of N. Va. be correctly transmitted to posterity. This is the only tribute that can now be paid to the worth of the noble officers and soldiers….” Explaining that many of his military papers from late 1864 through Appomattox had been lost in the retreat, Lee requested copies of all pertinent materials, often with personalized notations regarding specific reports or information he hoped to obtain.

When word of what he was doing inevitably leaked to the press, Lee received supportive letters from across the country. It was the fervent wish of one North Carolinian that he “should favor the world with your version of the matter, because we believe it will be the only true history that will be written on this painful subject.” The response was not limited to the South; from Philadelphia, William B. Reed wrote to suggest that Lee get cracking. “It should be done while every thing is fresh,” he said. In a rare response to a private letter on this subject, Lee hastened to assure Reed that “it is my purpose, unless prevented, to write the history of the campaigns in Virginia.” By all appearances, Lee’s intended tribute to the Army of Northern Virginia’s historic campaigns was on a fast track.

Richardson was not the only publisher who saw value in having Robert E. Lee’s name on a title page. Cincinnati-based Joseph L. Topham, representing “the largest book-publishing house in America,” offered an advance of $50,000, while S.S. Scranton and his partner promised “to make an offer for the work far exceeding in amount what we have heretofore thought of.” (Richardson was proposing no money up front, with Lee’s income to be a percentage of sales.) E.J. Hale pitched his own impeccable Southern credentials in his approach. Only the harsh fortunes of war had forced him to relocate his business from North Carolina to New York, he wrote, since his family had “staked nearly our all upon the cause of the Confederacy & lost it.” Lee’s older brother, Charles Carter, weighed in, suggesting that if Robert self-published the book it ought to bring in “at least $100,000.” There was strong interest expressed by British publishers, as well as offers to translate the work into French, German and Italian. In all, at least 11 different publishers approached Lee.

Lee’s replies were invariably courteous but firm. “I cannot now undertake the work you propose,” he told Scranton, “nor can I enter into an engagement to do what I may not be able to accomplish.” If anyone had an inside track it was Richardson, who kept Lee supplied with newly issued books on the war and even managed to locate some manuscript reports. Lee did agree to edit and write a new introduction to his father’s Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States, which University reprinted.

Richardson soon learned that Lee could be pushed only so far. When he tried to sweeten the pot by contributing 37 recently published history books to the library of Washington College (where Lee was president), he received a sharp note indicating that Lee considered the gift to be “irrespective of any profit you may expect to derive from the sale of the work I have contemplated publishing….” When Lee later learned that a prospectus listing works in preparation for Richardson’s company included the proposed “History of the Campaigns of the Army of Northern Virginia,” he insisted the notice be removed. These were just small bumps in their relationship, however. Even though there was no formal contract between the two men, had Lee seen the book through to completion, Richardson almost certainly would have been its publisher.

After 1866 Lee put the military history project aside, having never progressed past a few pages of memoranda on several of his wartime campaigns. Yet it would be wrong to conclude that he had not thought or talked about what he would say. Based on notes of conversations with him, as well as public statements and his private correspondence, we can gain insight into what he would likely have written.

Lee had been stung by articles in Northern newspapers branding him a traitor for having forsaken his West Point allegiances, so he would have undoubtedly prefaced his history by defending his actions. As he explained to a Confederate veteran and Washington College faculty member, he attended the military academy representing the state of Virginia, “who was entitled to this, and he could not see that it at all lessened his obligation to obey her.” And where went Virginia, so went Robert E. Lee. Testifying before Congress in early 1866, he explained that he looked “upon the action of the State, in withdrawing itself from the government of the United States, as carrying the individuals of the State along with it; that the State was responsible for the act, not the individual,” and “the act of Virginia, in withdrawing herself from the United States, carried me along as a citizen of Virginia, and that her laws and her acts were binding on me.”

Lee believed that secession was “a constitutional maxim at the South…, that they were merely using the reserved right which they had a right to do.” He understood further that the “position of the two sections which they held to each other was brought about by the politicians of the country; that the great masses of the people, if they understood the real question, would have avoided it.” As to citizens such as himself, they “looked upon the war as a necessary evil and went through it.”

Concerning his resignation from the U.S. Army, Lee felt “it was a hard thing for him even, thinking, as he did that Secession was foolish and the war wrong, to break loose and come South.” When he resigned, Lee believed the chances for martial conflict between North and South were slight. “I did believe at the time that it was an unnecessary condition of affairs, and might have been avoided if forbearance and wisdom had been practiced on both sides,” he said, and he sincerely “hoped and believed even after resignation that there would be peace, and intended to live in retirement.” Following a meeting with Virginia’s Governor John Letcher, Lee accepted the commission to command the state’s military forces, although he was a little fuzzy whether or not he actually swore an oath of allegiance to the newly minted Confederacy. “If it was required, I took it; or, if it had been required, I would have taken it; but I do not recollect whether it was or not,” he told Congress.

Following short periods of service in western Virginia and along the South Carolina coast, as well as stints as military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia after General Joseph E. Johnston was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines. Lee’s immediate impulse was to go on the attack. “When he took command,” related one confidant, “he found it would be necessary to strike a blow, that most of the Generals in the army were opposed to this….But he thought it would never do, and he proposed to Mr. Davis to bring down [Stonewall] Jackson [from the Shenandoah Valley], & gather all and make an attack on McClellan.” Lee was very much dissatisfied at his failure to wreck McClellan’s command in a series of savage battles collectively known as the Seven Days’, as his final report made plain. “Under ordinary circumstances,” he wrote, “the Federal army should have been destroyed.” A letter to his wife penned in early July 1862 voiced his underlying motives: “Our enemy has met with a heavy loss from which he must take some time to recover & then recommence his operations.”

Following the Second Battle of Manassas in late August, Lee boldly decided to move his army into Maryland and perhaps even Pennsylvania. In an 1868 letter he explained: “I will state that in crossing the Potomac I did not propose to invade the North, for I did not believe that the army of N.Va. was strong enough for the purpose, nor was I in any degree influenced by popular expectation. My movement was simply intended to threaten Washington, call the Federal army north of that river, relieve our territory and enable me to subsist the army….After reaching Frederick City, finding that the enemy still retained his positions at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry, and that it became necessary to dislodge him, to open our communications through the valley for the purpose of obtaining from Richmond the ammunition, clothing &c which we were in great need; [so] after detaching the necessary troops for the purpose, I was left with but two divisions, Longstreet’s and D.H. Hill’s, to mask the operation.”

Lee had counted on McClellan acting with the same degree of caution he had demonstrated during the Seven Days’ Battles and was surprised when the Union general moved quickly against his scattered forces. Only afterward did the Southern commander learn that the Federals had obtained a wayward copy of his own general orders. Still, he wanted there to be no doubt that his ultimate objective was to shatter the Union army.

“Had the Lost Dispatch not been lost,” Lee stated, “and had McClellan continued his cautious policy for two or three days longer, I would have had all my troops reconcentrated on Md. Side, stragglers up, men rested & I intended then to attack McClellan, hoping [for] the best results from state of my troops & those of the enemy. Tho’ it is impossible to[o] to say that victory would have certainly resulted, it is probable that the loss of the dispatch changed the character of the campaign.”

When it came to Gettysburg, Lee found it hard not to be critical of several key subordinates, with his most specific negative assessments centering on Second Corps commander Richard S. Ewell and cavalryman J.E.B. Stuart. As Lee explained in one postwar conversation: ”Stuart’s failure to carry out his instruction forced the battle of Gettysburg, & the imperfect, halting way in which his corps commanders (especially Ewell) fought the battle, gave victory…finally to the foe.”

Lee insisted that he had not taken his army into Pennsylvania looking for a fight. According to one confidant: “He expected however probably to find it necessary to give battle before his return in the Fall, as it would have been difficult to retreat without it….He expected therefore to move about, to maneuver & alarm the enemy, threaten their cities, hit any blows he might be able to do without risking a general battle, and then towards Fall return nearer his base….As for Gettysburg—First he did not intend to give general battle in Pa. if he could avoid it—The South was too weak to carry on a war of invasion, and his offensive movements against the North were never intended except as parts of a defensive system.” Once he stumbled into a major engagement at Gettysburg, The Confederate commander said on several occasions that he felt he had no choice but to fight.

Writing in 1868, Lee offered his own take on the battle: “Its loss was occasioned by a combination of circumstances. It was commenced in the absence of correct intelligence. It was continued in the effort to overcome the difficulties by which we were surrounded, and [success] would have been gained, could one determined and united blow have been delivered by our whole line. As it was, victory trembled in the balance for three days, and the battle resulted in the infliction of as great an amount of injury as was received, and in frustrating the Federal campaign for the season.” Thinking about Gettysburg reminded Lee even more forcefully how much he and the Confederacy had lost with the death of Stonewall Jackson after Chancellorsville, for, as he wrote, “if Jackson had been at Gettysburg they would have gained a victory.”

One major theme that emerges from Lee’s postwar commentaries is the disparity of numbers facing him—a view at sharp variance with his pugnacious 1862 outlook. When he first took command, he sought to stamp out defeatism among his generals—who were only too aware of how badly they were outnumbered. He cut short one officer’s accounting with the comment, “if you go to ciphering we are whipped beforehand.” The postwar Lee saw things in a different light. As he said: “the force which the Confederates brought to bear was so often inferior in numbers to that of the Yankees that the more they followed up the victory against one portion of the enemy’s line the more did they lay themselves open to being surrounded by the remainder of the enemy.” To Jubal Early, Lee confided that it would be “difficult to get the world to understand the odds against which we fought.”

Another topic Lee would have been unable to ignore involved the mistreatment of Union prisoners of war. As he testified to a Congressional committee: “I never knew that any cruelty was practiced, and I have no reason to believe that it was practiced. I can believe, and I had reason to believe, that privations may have been experienced among the prisoners, because I know that provisions and shelter could not be provided them….I never had any control over the prisoners, except those that were captured on the field of battle. Them it was my business to send to Richmond to the proper officer, who was then the provost marshal general. In regard to their disposition afterwards I had no control. I never gave an order about it. It was entirely in the hands of the War Department….”

Lee was not without opinions about what the Confederacy should have done to secure its independence. “He claimed that he knew the strength of the United States Government; and saw the necessity at first of two things—a proclamation of gradual emancipation and the use of the negroes as soldiers, and second the necessity of the early and prompt exportation of the cotton,” reported one postwar interviewer.

In undertaking to write about the Army of Northern Virginia’s campaigns, Lee professed no personal agenda. Speaking with a colleague, he said “he had fought honestly and earnestly to the best of his knowledge and ability for the ‘Cause’ and had never allowed his own advantage or reputation to come into consideration. He cared nothing for these, success was the great matter.”

All these observations indicate that Lee had likely been getting his thoughts in order about the war soon after it ended. In fact, he was still referring to the project as late as a few months before his death. Yet he never wrote the book. Why? Answering this question takes us into the realm of speculation.

Some of the reasons are obvious. By the fall of 1865, he had what was very much a full-time job as president of Washington College in Lexington, Va. Besides being driven by his own work ethic, Lee was inspired by the opportunity to help guide a future generation of Southern leaders. “No one can have more at heart the welfare of the young men of the country than I have,” he explained. “It is the hope of doing something for the benefit of those at the South that led me to take my present office.” Family matters preyed on him as well, not to mention the hundreds of appeals he received from veterans. And his own health noticeably declined soon after the war ended.

Still, in wartime Lee had shown himself capable of handling many disparate tasks; had he been as determined in 1867 to produce his history as he sounded in 1865, it seems likely he would have found a way to do it. From the beginning he framed his core motivation as a simple quest. “My only object is to transmit, if possible, the truth to posterity,” he told Jubal Early in 1865, “and do justice to our brave soldiers.” But it’s likely that the deeper Lee delved into the realities of writing such a book, the more he saw the hazards.

Curious as it may seem, given his subject, Lee did not relish the prospect of creating controversy. In a telling moment, he offered a critique to Stonewall Jackson’s widow after receiving an advance copy of an adulatory biography of her husband by R.L. Dabney: “I should have liked it more had questions and topics, calculated to excite unpleasant discussion, been omitted. I think its publication would then produce more general pleasure and satisfaction.” In a follow-up note he added: “I was also of opinion, that when the account[s] of the military operations became public, that those of the other corps of the army might reasonably think that less weight than was due had been given to the effect they produced in the result of a general action, and that thus an unpleasant discussion might be produced in the public papers, which would be to me a cause of regret.”

Pressed by Joe Johnston for support about issues he had had with President Davis and some subordinates, Lee responded: “I very much regret the revival of these questions now, as I do not think it will produce good.” After Early showed him some of the material he was preparing for publication, Lee strongly advised him to “omit all epithets or remarks calculated to incite bitterness or animosity between different sections of the Country.” The partisan agendas that emerged in the first wave of Southern postwar historiography deeply upset Lee. “It will be some time before the truth can be known,” he said in late 1865, “and I do not think that period has arrived.”

Then too, Lee was a realist when he came to assessing his own skills for the task, telling one interviewer that “he was hardly calculated for a historian. He was too much interested and might be biased.” It is worth noting that most of his official reports were drafted first by his staff, then reviewed and revised by Lee. The one proposal offered by Charles B. Richardson that Lee did accept was to write an introduction to the Revolutionary War memoirs originally published by his father. The results are best described by one of the general’s most recent biographers as “pretty pedestrian and quite uncritical.” Whether Lee would have sought or even accepted help from a professional co-writer is not known.

From the letters he received about his anticipated project, Lee could see that expectations were incredibly high—starting with his friend Beverley Tucker, who proclaimed: “No work in the 19th century has ever had, or ever will have, such a sale. Every man, woman, & child, who can read, will deny themselves the luxuries or even necessaries, if need be, to have Robert E. Lee’s History of the American War.” From a Texan, the former general learned that in “common with the whole civilized world, we rejoice that there is hope of one record of that terrible conflict of the nations, which shall be characterized by the magnanimity & truth & justice that are the ruling principles of your life.” For an experienced writer, such expectations could be a tonic; for Lee, a first-time author, they established a bar that loomed agonizingly beyond his abilities—at least his own perception of his abilities.

It is a final irony that Southern citizens, who saw Lee as the only man capable of telling the world the true story of their struggle for independence, may bear the heaviest responsibility for killing his “History of the Campaigns of the Army of Northern Virginia.” In this case it wasn’t anger or distrust that did the deed; instead, it was a profound, deep and ultimately suffocating love that stopped Robert E. Lee, amateur historian, dead in his tracks.

Noah Andre Trudeau is the author of many books, including Robert E. Lee: Lessons in Leadership (2009).

Originally Published in August 2010 Civil War Times