During World War II the U.S. military developed rudimentary capabilities to rescue downed aircrew members who ditched in the sea—a scenario that until then had usually amounted to a death sentence. Amphibious aircraft, originally designed for maritime patrol, were repurposed for search and rescue, augmented with pursuit and small liaison airplanes for searching and bombers retrofitted for dropping life rafts and other supplies. In the last months of the war, tiny helicopters introduced in the China-Burma-India Theater proved their worth for picking up airmen downed on land.

Search and rescue came of age during the Korean War with the advent of more-capable helicopters and an amphibious aircraft designed specifically for the SAR mission, the Grumman SA-16 Albatross. In Korea the U.S. Air Force’s Air Rescue Service extracted nearly 1,000 personnel from hostile territory. After the war, however, military strategies centered on nuclear weapons, and SAR during a nuclear war seemed ludicrous: There would be no one left to rescue. Air Rescue Service crews no longer trained for combat conditions and mostly flew support missions following peacetime accidents.

In November 1961, USAF crews began training South Vietnamese pilots in counterinsurgency operations using older aircraft such as North American T-28 trainers and Douglas B-26 bombers. Despite the stated goal of training, U.S. crews were soon flying combat missions against the Viet Cong.

The Air Force was initially reluctant to station dedicated SAR aircraft in Vietnam since their presence would indicate U.S. involvement in combat. Instead, a handful of assigned rescue coordinators relied on Army helicopters and the CIA’s Air America, neither of which had crews trained for combat SAR. Even if the Air Force had been willing to send SAR aircraft to Vietnam, Air Rescue Service equipment was woefully inadequate, suited mostly for firefighting support and rescues near a base.

Air Force Major Alan W. Saunders arrived at Tan Son Nhut Air Base near Saigon in June 1963 to work at Detachment 3, Pacific Air Rescue Center. Saunders knew from his WWII experience in Burma that finding downed aircraft in jungles could be difficult. When an airplane hit the jungle canopy, the trees opened up, the machine dropped in and the trees closed back over with nary a dent in the foliage. Even a fire usually left no burn mark.

By the time Saunders arrived, scores of servicemen had been lost. That September, the major and his staff wrote a report to justify the use of professional Air Force SAR units and sent it up the chain of command. As the report crawled through layers of bureaucracy, Saunders fumed at what he viewed as ineptitude that cost lives. In November a U.S. Army helicopter crashed into the ocean at night off the South Vietnamese central coast. All four crew members survived the crash, but while they swam about in their floatation gear expecting to be rescued, the Army’s higher-echelon commander decided not to send helicopters: His pilots weren’t trained to fly at night, which is what had caused the accident in the first place. The copilot swam to shore with a broken arm and hid overnight in bushes. The other three crewmen drowned.

Despite the primitive conditions and equipment, Saunders’ unit found all but two of the nearly 250 aircraft they searched for during his tenure. When searchers couldn’t find downed airmen, Saunders suspended the mission and aircraft then often dropped leaflets offering rewards. The rewards were for turning in equipment, not people, since the Geneva Conventions forbid ransoms. Saunders figured it was okay to say, “We’ll give you 35,000 dong for the parachute if the man is with it, or…17,000 dong if he isn’t with it.” The leaflets rarely worked; he was aware of only one instance when a leaflet drop resulted in someone coming forward, and that information turned out to be useless.

On March 26, 1964, Captain Richard L. Whitesides, who months earlier had become the first Vietnam War recipient of the Air Force Cross, took off from Khe Sanh, just south of the DMZ, in a single-engine Cessna O-1 for a two-hour visual reconnaissance mission. Army Special Forces Captain Floyd J. Thompson accompanied him as observer.

After the O-1 failed to return, dozens of flights searched for 16 days around mountainous terrain covered with dense jungle teeming with Viet Cong. More than 200 South Vietnamese soldiers and U.S. Special Forces personnel joined a ground search, which turned up several villagers who claimed they had seen a small aircraft flying just above treetop level, spewing smoke. More searching and the offer of a reward turned up nothing.

The search was suspended on April 11 and 200,000 leaflets were dropped. On May 21 a defector reported having seen Viet Cong forces shoot down an O-1 in late March. He said one of the Americans was killed in the crash and the other was wounded and captured. The report renewed a flurry of searching, but two weeks later the jungle still refused to surrender the O-1.

On June 2 the U.S. dropped an additional 100,000 reward leaflets. Radio Hanoi broadcast a statement on November 4 from Captain Thompson, who had been captured by guerrillas. He was released in 1973 at the end of the war. It took another four decades to recover Whitesides; his remains were identified in 2014.

After months of Air Force and Army wrangling over ownership of the search-and-rescue mission, Saunders finally received approval to move SAR units to Southeast Asia. He wanted four units with Kaman HH-43B Huskie helicopters, but Air Rescue Service planners instead chose only two units with Sikorsky CH-3s, which Saunders considered too big for Vietnam’s jungles and rugged terrain. And more than two units were needed to cover the vast north-south distances in Vietnam. Still, it was better than nothing.

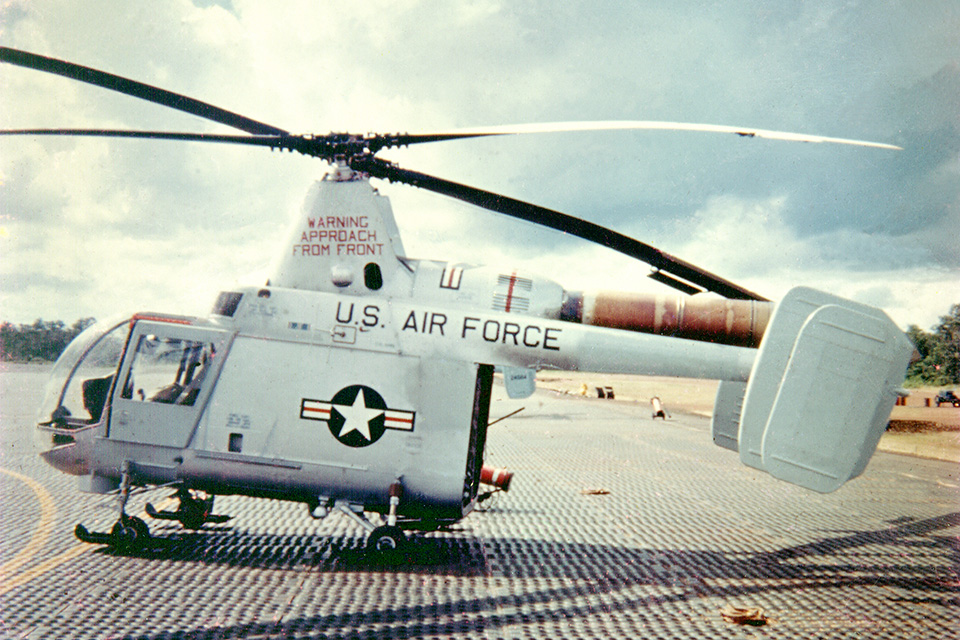

Throughout the summer of 1964, Saunders continued advocating for HH-43Bs, even though they, like the CH-3s, weren’t outfitted for combat and were primarily used for crash rescue. When an aircraft crashed, a Huskie was airborne in less than 90 seconds. Slung beneath the helicopter was a fire-suppression kit, nicknamed “Sputnik,” that carried a spherical fire extinguisher about three feet in diameter, hoses and other rescue equipment. At the crash site, the HH-43B crew dropped off the Sputnik and one or more firefighters, who laid a path of foam toward the burning wreckage while the helo pilots hovered 10 feet above, using air from their contrarotating rotors to push the foam along the path and create a safe corridor for rescuers to pull survivors to safety.

Saunders asked that any Huskies sent to Vietnam be modified for combat with upgraded engines, self-sealing fuel tanks, shatterproof glass, armor plating and gun mounts on the doors. But Kaman told the Air Force it would take another three months to modify the helicopters, so it would be at least September before the newer aircraft, the HH-43F, arrived.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

In June 1964 two unmodified HH-43Bs from Okinawa arrived at Nakhon Phanom (NKP) Royal Thai Air Force Base (RTAFB) near the Thailand-Laos border. Two Albatross amphibians (now designated HU-16s) also arrived at Korat RTAFB near Bangkok, followed by two more HU-16s at Da Nang Air Base on South Vietnam’s east coast.

A few days after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in August, Detachment 2 of the Central Air Rescue Center at Minot AFB in North Dakota got orders to deploy to Vietnam. The unit had only two helicopters and they both needed major maintenance, so someone borrowed two serviceable HH-43Bs from nearby Grand Forks AFB. Maintenance personnel at Minot disassembled the loaners and loaded them onto a Douglas C-124 cargo plane as Huskie pilot 1st Lt. John Christianson and his squadron mates rushed about, getting their personal affairs in order and collecting equipment for their deployment.

After hopscotching on a C-130 across the U.S. and Pacific, the detachment finally landed at Da Nang, where Christianson recalled the base commander greeted them with, “Who the hell are you and what are you doing here?”

There wasn’t much action at first for the HH-43Bs. The Huskies were assigned to missions over land but many downed aircrews made it to the Gulf of Tonkin, where the Albatrosses or Navy helos picked them up.

In November a unit equipped with the HH-43F models that Saunders coveted arrived from the U.S. to replace Christianson’s unit. Rather than return to the States, Christianson, along with another pilot, Jim Sovell, went to NKP in Thailand to replace two pilots.

On November 18, right after Christianson and Sovell arrived at NKP, F-100 Super Sabre pilot Captain Bill Martin was downed by anti-aircraft artillery while escorting a reconnaissance mission in Laos. He ejected near the border with North Vietnam and his wingman radioed for help. An Air America aircraft responded first, but an HU-16 soon arrived, followed shortly by two Navy Douglas A-1 Skyraiders. The “Spad” pilots took out the gun emplacements with their 20mm cannons and spotted the F-100 wreckage. The HU-16 called NKP and asked for helicopters to fly to the wreckage and pick up Martin.

After two HH-43s were refused entry into Laos because the U.S. ambassador in Vientiane hadn’t given his permission to cross the border, someone called the embassy to get authorization. Christian-son and Sovell got in on the action, flying their Huskies straight across the Mekong River into Laos to meet the waiting Spad and HU-16 pilots, who escorted them to the crash site. But an extensive search came up empty-handed.

Overnight the SAR center coordinated 31 aircraft to search the next morning: 13 USAF Republic F-105 fighters, eight F-100s, six Navy Spads, two HH-43s and two Air America helicopters. At that point, it was the largest number of aircraft assembled for a SAR mission in Vietnam.

By mid-morning an HU-16 and four F-105s had sighted Martin’s parachute near his F-100 on a prominent limestone karst outcrop. As the F-105s attacked a nearby gun emplacement, the HU-16 brought in the two Air America helicopters, escorted by four T-28s. The copilot of one of the helicopters was lowered on a hoist to the parachute, but Martin was dead, having apparently succumbed to injuries from landing on the jagged limestone terrain.

The rescue forces mourned Martin’s death, but the coordinated effort that found and recovered his body proved that SAR in Southeast Asia was starting to mature.

On February 13, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson authorized the campaign of airstrikes in North Vietnam designated Operation Rolling Thunder. USAF aircraft poured into Southeast Asia, along with additional Navy ships and aircraft carriers.

Albatrosses operating from Da Nang had a brief heyday during Rolling Thunder, rescuing 35 U.S. airmen and one South Vietnamese pilot who bailed out over the Gulf of Tonkin. Every day an HU-16 departed Da Nang just before sunrise and orbited in a racetrack pattern about 20 miles off the coast of North Vietnam until noon, then a later shift orbited from noon until sunset. The HU-16’s navigator helped maintain the aircraft’s position via radio using the Tactical Air Navigation (TACAN) system carried aboard a Navy destroyer in the gulf.

As the Albatross flew its pattern, armed aircraft orbited near it in a rescue combat air patrol (RESCAP), using their guns if needed to ward off hostile boats or land forces that might converge on any downed aircrew. The low-and-slow prop-driven A-1s were best for RESCAP. A Spad pilot could spot ground targets more easily than a jet pilot and the A-1 usually carried more ammunition, could loiter longer and its armor-plated underbelly could take a huge amount of punishment from small-arms fire.

If an aircraft went down, the pilot’s wingman broadcast its position over the radio. The Albatross and RESCAP aircraft headed toward the location, with the speedier RESCAP aircraft usually arriving first. They fired warning shots across the bow of any threatening sampans or junks and shot the boat if it kept approaching. If survivors weren’t in immediate danger and a Navy helicopter happened to be nearby, Albatross crews usually waited for the helo to make the pickup, since the HU-16 was prone to damage during water landings. The Albatross crew might drop a smoke flare to mark the spot, or in some cases they dropped the flare away from the pilot and circled above the smoke to deceive any hostile forces.

On November 1, 1965, an Albatross crew earned Silver Stars for a rescue under fire. Captain Dave Westenbarger and copilot Captain Dave Wendt had been almost ready to return to Da Nang at the end of their shift when an Air Force F-101 Voodoo was shot down. Two A-1s from the carrier Oriskany orbiting with them headed for the downed pilot, Norman Huggins. He had landed in the water but was close to an island and swam ashore, where North Vietnamese spotted him and chased him back into the water. While he used his .38 pistol to keep his attackers at bay, the Albatross arrived.

The HU-16 crew had to jettison their external fuel tanks before they could land on the water, but the left tank didn’t drop away. Westenbarger and Wendt decided to land anyway, and as they lowered their flaps and slowed down, the tank fell off. Then two sampans fired at the Albatross and one of the Spad pilots launched several rockets at the lead boat, destroying it. The HU-16’s propellers made a sickening sound as they shredded the sampan’s wooden debris, but the Albatross emerged unscathed. The second sampan turned and fled.

After chasing away another enemy swimming toward Huggins, the HU-16’s pararescue jumper, Airman 1st Class James Pleiman, went into the water and pulled him to safety. Westenbarger and Wendt delivered him to Da Nang, where the grateful pilot bought drinks for everyone. Four months later, Pleiman was killed during an attempt to rescue an F-4 crew from the gulf.

By late October 1965, several Navy crews back in the States were training for combat operations in Kaman UH-2 Seasprites that had been modified with armor and more powerful engines. But as combat operations in the gulf increased, commanders began to ask more from unmodified Seasprites already in theater. On November 8 a UH-2 from helicopter squadron HC-2 was sent to the frigate Richmond K. Turner as a last-ditch back-up for an overland combat SAR mission that had kicked off on November 5 after an F-105 crashed. Two A-1s and a CH-3 were shot down during the rescue attempt, and an SH-3 helicopter crash-landed on a 4,000-foot mountain after running out of fuel. The desperate task force commander dispatched the only helicopter he had left, the UH-2 sitting on Turner. Arriving at the mountaintop, the underpowered helo pulled two of the four downed aircrew aboard. An Air Force helicopter arrived later to rescue the remaining crewmen.

The UH-2 had been staged on Turner for a single mission, but someone soon decided to routinely keep helicopters onboard smaller, more maneuverable ships that could operate farther north and closer to Vietnam’s shore than lumbering aircraft carriers. Exactly who made the decision is lost to history, but on November 8 a UH-2 from Oriskany’s squadron HC-1 was dispatched to the guided-missile cruiser Gridley.

Pilots Lieutenant Tom Saintsing and Lt. (j.g.) Jim Welsh, along with Airman James Hug and Petty Officer 3rd Class John Shanks, were the guinea pig crew. They landed on Gridley’s fantail, on a spot barely big enough for one helicopter. Saintsing recalled Gridley’s captain greeting them with: “I know nothing about helicopters. You’re going to have to tell me what to do and how to do it.”

With limited rescue experience and no combat time, Saintsing and Welsh barely knew what to do themselves. But once aboard Gridley they didn’t have long to wait for some action. Weather closed in the second day of their stay and waves tossed the cruiser about. At about 2 a.m. someone woke the crew and sent them to retrieve Lt. Cmdr. Paul Merchant, who had ditched his Spad about a mile offshore in the gulf after taking groundfire during a night reconnaissance mission.

A little over an hour later, Saintsing and his crew skimmed 200 feet above the black water. The weather was terrible, with 25-foot waves rising and merging with the dark sky. They were up against two North Vietnamese fishing boats and enemy forces on the beach who fired at them as they approached. Blue streaks from tracer fire filled the sky. No one on the helicopter had been shot at before and they didn’t even wear flak jackets. Their armament consisted of two Thompson submachine guns tossed aboard almost as an afterthought.

The helicopter won the race. Hovering above Merchant, the two enlisted crewmen lowered a rescue sling and reeled the pilot aboard.

Dangerously low on fuel, Saintsing turned back toward Gridley. Before they took off, he noted the Seasprite wouldn’t have enough fuel to fly the more than 200-mile round trip, so he asked the crew to steam toward the coast. Just before Saintsing touched down again around 4:15 a.m., the low-fuel light illuminated the cockpit.

On November 28 the first Seasprites equipped with armor plates and Navy crews specifically trained for the SAR mission arrived in the Gulf of Tonkin. Although SAR crews, equipment and techniques continued to improve throughout the war, the arrival of the modified Seasprites and the detachments of helicopters on smaller ships signaled that SAR in Southeast Asia was finally a mature mission.

Retired U.S. Air Force officer and former flight test engineer Eileen Bjorkman is a freelance writer and author of Unforgotten in the Gulf of Tonkin: A Story of the U.S. Military’s Commitment to Leave No One Behind, which is recommended for further reading.

This feature originally appeared in the March 2021 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!