You probably use one of William P. Lear’s inventions every day. No, not a Learjet—unless you’re richer than we reckon—but the practical, affordable, compact car radio.

It all started with Bill Lear’s prototype of an AM radio receiver small enough to fit into a 1920s automobile, which ultimately led to the development of a mega-billion-dollar corporation called Motorola. Lear, as was his wont, moved on to more challenging problems while Motorola was still a garage-size shop, and he continued through a lifetime of peaks and valleys to increase his patent tally—127 of them, some for major inventions, some for pointless trifles—by the time he died in 1978.

(San Diego Air & Space Museum)

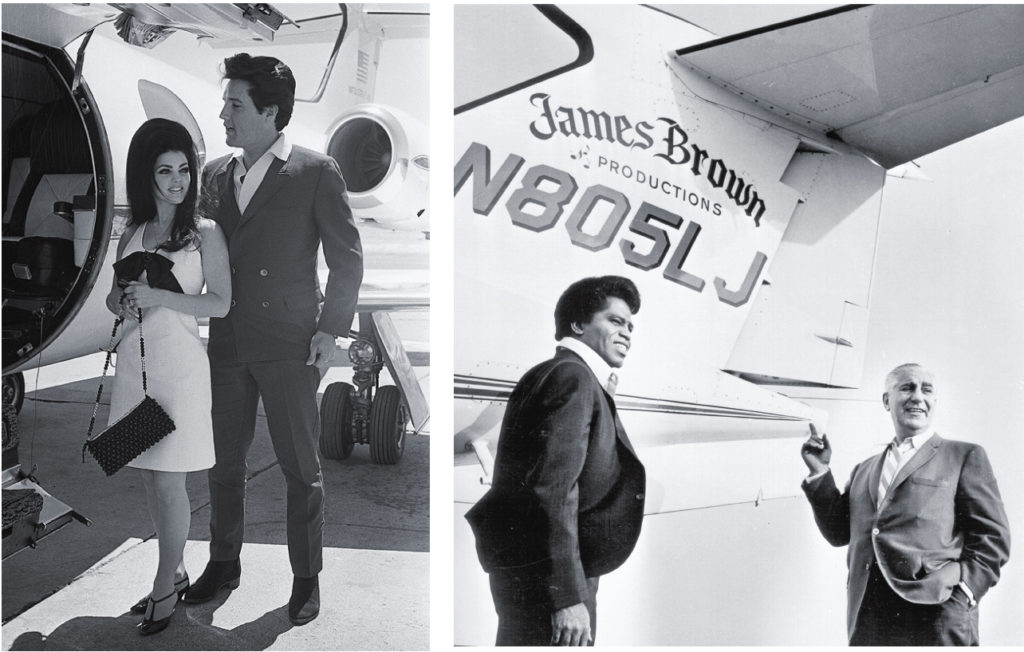

Bill Lear is popularly assumed to have been the designer of the Learjet, but he could no more have designed an airplane than an itinerant aviation writer could knock out a lightweight autopilot. (Such an autopilot was one of Lear’s greatest achievements.) Lear simply decided that the world needed a small, light and comparatively inexpensive business jet, and he hired good engineers to do the heavy lifting. The resulting Learjet became popular shorthand for any business aircraft. “Saying Learjet is like saying Kleenex even if the business aircraft on the ramp, like the tissue paper on the counter, is a different brand,” wrote Walter Boyne and Philip Handleman in The 25 Most Influential Aircraft of All Time. Owning a Learjet also became a winged symbol of success. Frank Sinatra bought one and enjoyed loaning it to his famous friends; golfer Arnold Palmer had one; Carly Simon mentioned the Learjet in her hit song “You’re So Vain.”

But Lear’s forte was electronics, not airplane design. It was once said that the great Lockheed aerodynamicist Kelly Johnson could “see” air, and perhaps Lear could see electricity. He designed lightweight avionics for general aviation, and he was the first to make light planes true traveling machines, able to fly long distances through bad weather and good, with navigation radios to help pilots find their way. Until Bill Lear came along, only airliners and some military aircraft carried radios.

Lear may not have been an aeronautical engineer, but he was many other things: an entrepreneur and visionary, a salesman who could sell a stereo to a deaf Inuit, a serial philanderer, charmer and best friend of everyone he met, particularly the journalists who watered at his trough. His formal education ended after eighth grade, but as one engineer friend said, “Bill didn’t have the limitations of an education. He didn’t know what couldn’t be done.”

George C. Larson, editor emeritus of Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine, was one journalist who covered Lear. “Bill’s overwhelming talent was that he knew how to charm people,” says Larson. “He never met a stranger. He was totally gregarious and always assumed that you loved him. And it stood him in good stead in front of the press, though one of his problems was that sometimes he believed his own press.”

Lear also had a colorful personal life. He was never classically handsome and became increasingly pudgy as he aged, but he often had lots of money and always had lots of charisma. Both attracted women. He never lacked for mistresses. His fourth wife, Moya, once made him a needlepoint adorned with the names of 13 of his girlfriends—not a complete list, just the ones she knew about. The marriage worked well because Moya’s rule was that her husband could have all the lovers he wanted as long as he didn’t talk about them.

Moya was the daughter of vaudeville comedian John “Ole” Olsen, of the duo Olsen and Johnson. It has long been assumed that Bill Lear was the wit who named one of his daughters Shanda, thus condemning her to a life of being introduced as Shanda Lear, but the name was in fact grandpa Ole’s idea.

It couldn’t have been easy to be one of Lear’s children (and he had seven). Lear’s son John once crashed a Bücker Jungmann biplane while he was showing off with aerobatics above his Swiss prep school. Bill had to pay for the airplane. He never forgave John and left him $1 in his will, “which, incidentally, I never got,” John Lear recalls. John once asked his father for airfare to fly John’s girlfriend from Geneva to Los Angeles. In his excellent biography Stormy Genius, Richard Rashke reports that Bill said that if he paid for her trip, he and not John would be the one to sleep with her.

William Powell Lear was born on June 26, 1902, in Hannibal, Missouri, and later moved to Chicago with his mother after she divorced. He developed a love for airplanes, even though his first flight, when he was 17, ended in a minor crash. His second ride was to be aboard a Goodyear blimp, but he was bumped by a photographer at the last minute. The blimp crashed and the cameraman died.

Lear was undeterred. Following a stint in the Navy, he learned how to fly while working at a Chicago airport. After selling his interest in Motorola, in 1931 he bought a fast Monocoupe, which he flew from Chicago to Miami, trying to follow the crude Department of Commerce radio beacon system. He ran into bad weather and was fortunate to survive. Chastened, Lear called a friend to pick him up and hired a pilot to fly the Monocoupe back to Chicago. (Lear once said that if you try to fly through no-visibility weather without knowing how, “You’ll be instrument flying for the rest of your life…about a minute and a half.”) Lear immediately began working on a light, practical radio direction finder that could home in on commercial broadcast stations. He marketed it as the Learoscope but couldn’t afford a patent attorney, so his development went unprotected from competitors such as Bendix. But Lear undoubtedly contributed more to the development of the radio direction finder than any other inventor.

Above all, Lear loved a challenge. He left the mundanities of producing and marketing his inventions to others while he chased new opportunities. The greatest of these, in his mind, was the development of an airplane, and he ultimately left behind the gadgets, as he called them, to pursue that dream.

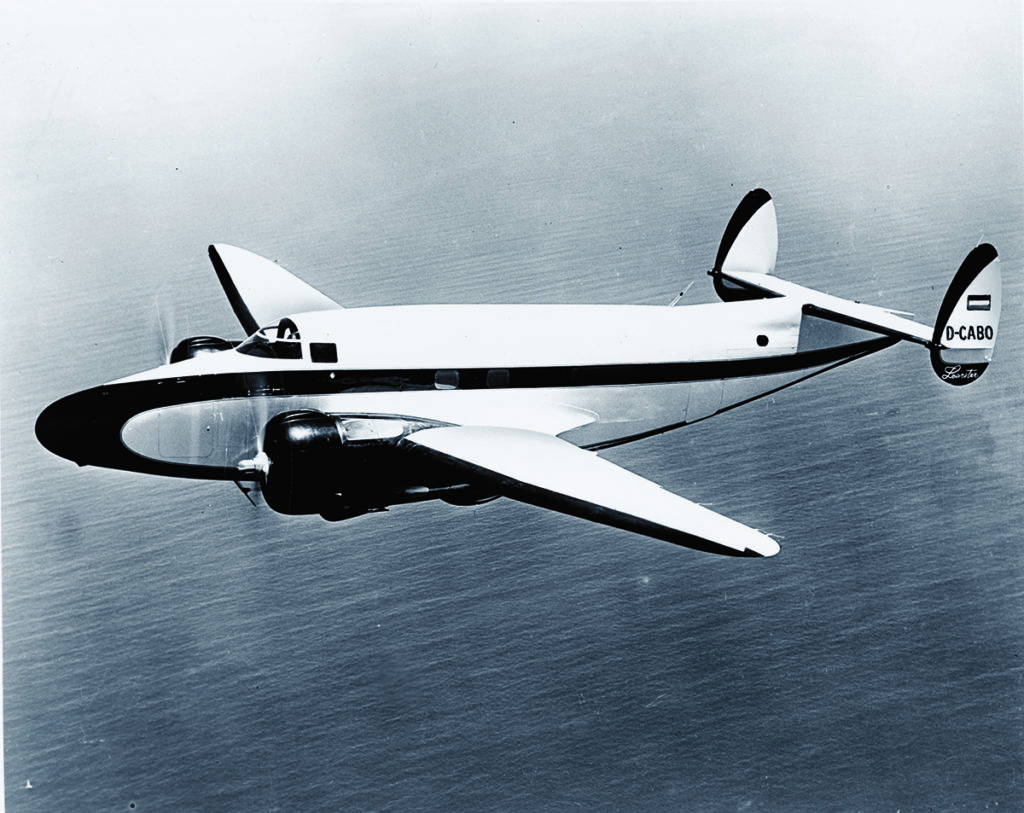

In the early 1950s the U.S. Air Force lent Lear an elderly Lockheed Lodestar transport to use for testing an autopilot and approach coupler for automated instrument landings that Lear was developing for military aircraft. Lear called the airplane the Green Weeniebut liked it enough to purchase it for pennies on the dollar. He did some drag-reduction work on the airframe and created a posh executive interior, ending up with one of the nicest corporate airplanes of the time. He sold the Green Weenie for $200,000 and bought two more surplus Lodestars for $70,000. Lear gave them the same executive facelift and realized he had the makings of an airframe business.

At the time, however, Lear’s company had a board of directors, and those directors were interested in making money, not airplanes. They told their CEO to drop the Lodestar project. Instead, Lear went behind their backs and formed the Lear Aircraft Engineering Division. Little did the directors know that Bill was also privately buying run-out Lodestars and then reselling them to his own airplane subsidiary at a handsome profit.

Lear was not an airplane designer, and he knew it. He hired some of the best-known aeronautical engineers in the business—Gordon Israel, Ed Swearingen and Benny Howard—to turn the Lodestar into the Learstar via a redesigned wing and other modifications. With a cruise speed of 300 mph and a range of 3,800 miles, the Learstar briefly was the fastest and longest-range twin-engine piston airplane in the world. Finally, Bill had found his true calling—building airplanes.

In 1955, Bill and Moya moved to Switzerland. He intended to set up a European subsidiary to sell his products internationally, but he had also bought into the legend that Swiss engineers were superb. Perhaps they could help him build his next airplane, whatever it might be. His relocation was probably hastened by the fact that his board of directors had learned about the Aircraft Engineering Division and were planning to shut it down. It didn’t help that the Learstar was losing money, a fact that Lear never admitted publicly. Nor did Lear’s general aviation compact avionics ever make much of a dent in a market dominated by Narco, Collins, Bendix and King.

In Switzerland Lear became intrigued by a new Swiss fighter-bomber, the Flug-und Fahrzeugwerke Altenrhein AG (FFA) P-16, that was intended to replace the Swiss Air Force’s aging British de Havilland Vampire first-generation jets. The P-16, however, never made it past the prototype stage. Four were built, and two ended up at the bottom of Lake Constance when their test pilots ejected after experiencing systems failures. The Swiss press began referring to the P-16 as “the Swiss Submarine,” but Lear liked its thin, fast, multi-spar, low-aspect-ratio wing.

So, Bill hired the P-16’s chief engineer, Hans Studer, to design a small business jet for the company Lear had already established in Switzerland and called the Swiss American Aviation Corporation—SAAC. He named his new airplane the SAAC-23.

There has been a long-running battle between those who claim the resulting Lear 23 was directly derived from the FFA P-16 and those who insist that the Learjet was an entirely new design with just a few features inspired by the Swiss jet. As recently as 2007, Lear’s son William P. Lear Jr. was moved to rebut an article in Aviation International News that ran “complete with references to the well-worn tale of the Swiss fighter connection.” Lear Jr., a former Air Force and Air National Guard fighter pilot, had flown the P-16 to evaluate it at FFA’s request, and claims that he was the source of his father’s interest in the design.

His rebuttal is not entirely convincing, for his five main points contain three clangers. First, Lear Jr. said the Lear 23 and the P-16 had “similar but not the same” airfoils. In fact, the first Learjet did utilize the P-16’s airfoil, although its leading edge was modified after a test pilot found that it had some squirrely handling and stall characteristics.

“The P-16 wing sweep was zero, while the Learjet’s was 13 degrees,” said Lear Jr. Not true; both aircraft had identical 13-degree leading-edge sweeps and straight trailing edges.

He also said, “The P-16 had a cruciform tail and the Learjet a T tail.” True of the prototype and production airplanes, but the scale model of the first Lear 23 proposal, as designed by Gordon Israel, had a cruciform tail like the P-16’s. It was changed to a T tail when the airplane turned out to be faster than expected and needed a horizontal stabilizer well out of the wing’s turbulent wake. (Lear famously called the revised design “the best-looking piece of tail I ever saw.”)

Whatever the case, engineer Israel, responsible for much of the Learjet’s design, did draft an entirely new internal structure for the wing, though he retained the Swiss multiple-spar concept. Both airplanes also included the distinctive wingtip fuel tanks.

Israel became involved after Lear summarily snatched SAAC out of Switzerland, renamed it Learjet Inc. and moved it to Wichita, Kansas, in 1962. As his son Bill Jr. recalls, “We bailed out of Switzerland [because] labor was half the price, but it took four times as long to get anything done.” Swiss engineers and technicians turned out to be better suited to creating wristwatches than airplanes. Israel was eventually fired, and the Model 23 design was completed by former Cessna engineer Henry Waring, who had been responsible for the Cessna T-37 Air Force primary trainer known as the Tweet, as well as the handsome Cessna 310 light twin.

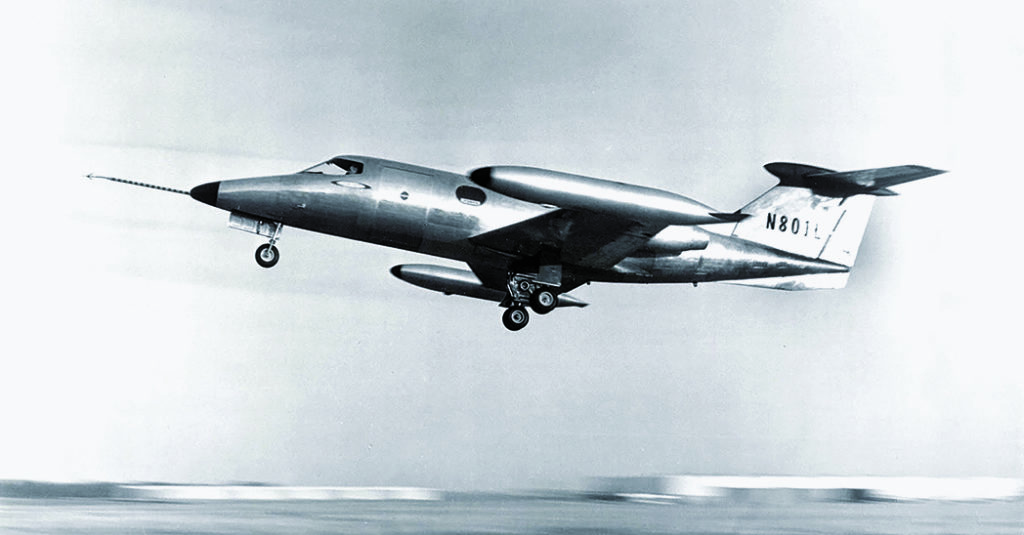

True to his all-or-nothing character, Lear took a major gamble with the Learjet 23. He didn’t build a prototype, a hand-built unit that could be tested for flaws and modified as necessary, with the changes then carried to the production line. Instead, he built his very first airplane using production tooling and jigs, and changing any of them would have been very expensive. (The wing’s leading edge was reprofiled, but that was a simple sheet metal modification.) “With this approach,” he said, “you’re either very right or very wrong.”

The first Learjet made its initial flight on October 7, 1963. On June 4, 1964, the FAA pilot flying it during certification testing forgot to retract the landing spoilers during a touch-and-go takeoff and the airplane ended up on its belly in a cornfield. There was little damage, but a fuel line broke and started a fire that reduced the airplane to cinders. “We just sold our first Learjet,” Bill said as he pocketed the insurance check. The FAA was embarrassed enough by the crash that it smoothed the path to certification as much as possible, and Lear had his jet approved that July 31, less than two months after the accident. Even more important, it received certification four months ahead of Lear’s biggest competition, the Aero Commander 1121 Jet Commander. The Lear 23 project cost Bill the equivalent of $112 million in today’s dollars. Never before had a single individual conceived, driven, produced and financed an aviation project of such magnitude. (During the certification process, Lear got a ride in a Lincoln Continental that had been outfitted with a Muntz Autostereo four-track tape deck. Never one to miss an opportunity, he immediately became a Muntz distributor, and within a year Lear had invented the first eight-track stereo deck, after being told it couldn’t be done.)

Soon after the Model 23 and a couple of follow-on versions flew, Lear became bored and sold his company to the Gates Rubber Company. (The resulting Gates Learjet Corporation compressed the original Lear Jet name into one word.) Lear moved on to other projects. None would ever achieve success in his hands.

His agreement with Gates forbade him from designing or building aircraft for five years, so Lear decided to solve the world’s air pollution problem by designing a steam-powered automobile. However, Lear’s grasp of automotive technology was mired in the 1940s. He considered research to be a trip to Harrah’s Las Vegas vintage-car museum and seemed to believe that all atmospheric contamination was caused by vehicles. “I want to be the man who eradicated air pollution,” he said. He intended the car’s engine, a steam turbine, to be powered by a closed-cycle superheated liquid he called Learium. (Lear named virtually everything he invented after himself.) The liquid was supposed to be denser than water so it would hold more heat, but Lear finally was forced to use plain distilled water.

He continued to call it Learium, though everybody knew it was a joke; he privately referred to it as Delearium.

The steam-car project failed miserably, appearing very briefly in prototype form as a clunky and impractical steam-powered bus, but Lear shouldered the blame. He reportedly said that if he had only read a physics textbook, he would have known that it would never work.

The aging entrepreneur still had a couple of airplanes up his sleeve, though by the time the first one flew, it bore virtually none of his DNA. He called it the Learstar 600, repurposing the name he’d used for his modified Lodestar. It was to be a spacious twinjet with a fast, efficient, supercritical wing and newly developed turbofan engines but it never advanced beyond a very preliminary paper concept limned by an outside consultant. By 1975, Lear had spent most of his fortune and couldn’t afford to do any more than dream about Learstar jets, but he managed to sell the dream to the Canadian company Canadair, which figured that it was buying not so much an airplane as Lear’s name.

Canadair inflated the already-rotund fuselage to mini-airliner size—the company called it a walk-around cabin and Lear referred to it as “Fat Albert”—and renamed the airplane the Challenger 600. Challengers are being built to this day, in three different sizes, as is a line of regional airliners based on the stretched Challenger and called CRJs. Canadair sidelined Bill Lear in 1977 and he had no involvement with either line of airplanes.

Bill Lear’s last airplane, the Lear Fan 2100, hadn’t flown by the time he died. Only three were built, and none were sold. They were manufactured almost entirely under the direction of Moya Lear and were riddled with structural and powerplant problems.

Yet it could have been one of the most important airplanes of its time, for the Lear Fan was made entirely of composites—carbon-reinforced plastics. Hard lessons learned during the prototyping of the Lear Fan are today reflected in a wide variety of composite-crafted aircraft from fighters to airliners.

(©Paul Bowen)

The Lear Fan was also a pusher, with its propeller at the tail end of the fuselage. That configuration allows an airplane’s fuselage, and some of its wing, to fly through undisturbed air, thus decreasing drag and increasing airspeed, range and efficiency. The Lear Fan’s single prop was driven by two turboshaft engines, through a troublesome gearbox that sought to combine their power.

The FAA had never certificated an all-composite aircraft, and some people involved with the Lear Fan project claim that the government’s demands for increased structural strength were two and three times greater—and heavier—than necessary. Throughout the process, the Lear Fan’s weight grew and performance shrank. The Lear Fan never came close to its initial performance predictions, the FAA ultimately refused to certify it and the Irish company formed to build it declared bankruptcy.

By then Bill Lear was gone, having died of leukemia in May 1978 at the age of 75. He may not have designed the business jet that bore his name, but he had certainly made an impact on aviation. Lear’s oft-stated mantra was, “Don’t nibble at a problem, take a big bite of it,” and he lived by those words. He did his best work well before people like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk made rogue entrepreneurship part of the mainstream, but they would have understood.

Stephan Wilkinson is Aviation History’s contributing editor. For further reading he recommends Stormy Genius: The Rags to Riches Life of Bill Lear by Richard Rashke; They Said It Couldn’t Be Done: The Incredible Story of Bill Lear by Victor Boesen; and Fly Fast…Sin Boldly: Flying, Spying and Surviving by William P. Lear Jr.

The Last Learjet

On March 28, 2022, Bombardier Aerospace, which had purchased the Learjet Corporation in 1990, delivered the last Learjet, a model 75. “There’s no doubt that today is an emotional day for many of us as it marks the end of the production era of Learjet,” said Bombardier’s vice president for Learjet operations, Tonya Sudduth. Since the first Learjet 23 flew in 1963, more than 3,000 airplanes with the name Learjet had been produced; around 2,000 are still flying. The line had gone through many changes and upgrades over its nearly six decades. Winglets replaced the original wingtip fuel tanks, fuselages became stretched and engines received upgrades. With the introduction of the Learjet 45 in 1998, Bombardier essentially parted ways with the original jet and began producing a wholly new airplane—but kept the iconic name. Bombardier announced plans to introduce an all-composite Learjet 85 but cancelled the project in 2015, making the Model 75 the end of the line. We will see no more airplanes bearing the name Learjet, but Bill Lear’s vision will remain the symbol of luxury private air travel for many.