In his youth, Lawrence Joel faced many challenges beyond the color of his skin. Born on Feb. 22, 1928, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, he spent his early years in poverty. The Great Depression took such a toll on Joel’s family that his parents separated six years later. Joel was raised by foster parents.

After graduating from high school in 1945, Joel joined the Merchant Marine. He enlisted in the Army a year later and went to jump school. Joel spent most of his tour in postwar Italy. Following his discharge he hoped to become a beautician but found his opportunities limited and returned to the Army in 1953. According to Time magazine, which interviewed Joel for a 1967 article on Blacks serving in Vietnam, he “was convinced that you ‘couldn’t make it really big’ as a Negro on the outside.” He became an Army medic, a role well-suited to his quiet, peaceful personality and desire to help others.

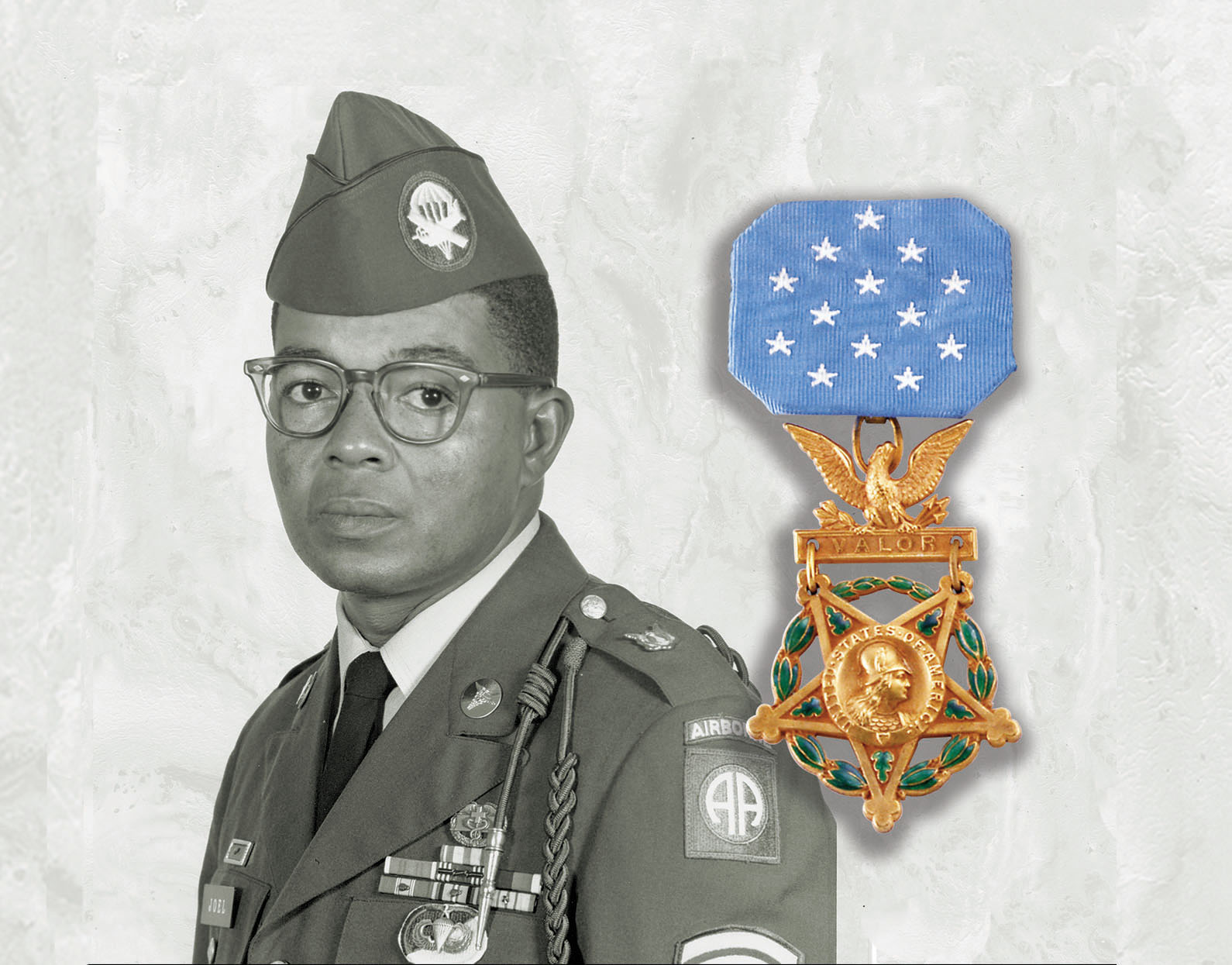

In 1965, Joel, then a 37-year-old specialist 5, was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment, 173rd Airborne Brigade, and sent to Vietnam. On Nov. 8 he accompanied an infantry company into a Viet Cong stronghold northwest of Saigon. Joel was unarmed and carrying a medical aid bag filled with bandages, syrettes of morphine, plasma and instruments.

After disembarking from helicopters, the lead squad was hit by withering fire from a well-hidden and much larger Viet Cong force. Nearly every man was killed or wounded. The remaining squads scrambled for cover to engage the enemy in what became a bitter 24-hour firefight.

Ignoring enemy fire, Joel rushed forward to reach the wounded and dead. As he darted from man to man, a machine-gun bullet struck him in the right leg. He paused long enough to rip open his pants, stuff a bandage into the wound and administer morphine to himself.

Hobbling across the battlefield, Joel patched up bullet wounds and gave mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Finding a man who needed blood, Joel knelt in full view of the enemy to hold the bottle high enough to administer life-saving plasma amid a hail of bullets. Joel saw one soldier with a chest wound bubbling out his last ounces of blood. He pressed a plastic bandage bag over it hoping to congeal the blood—and silently praying for a miracle. The soldier survived.

A second bullet lodged in Joel’s right thigh, but he dragged himself over the battlefield to treat 13 more men before his supplies ran out. Joel sent word that he needed more. While waiting, he shouted words of encouragement to men who seemed to have no hope. A soldier who crept forward with the supplies noted Joel’s ripped trousers and bloody, bandaged legs. “You better head back to the rear and get treatment,” he said.

“I’ll be all right,” Joel responded. As another platoon charged forward to dislodge the entrenched enemy, Joel followed, knowing there would be many more wounds. Throughout the day and into the night, he limped and crawled under deadly fire to aid and comfort his comrades, even though they urged him to get down and head to the rear for treatment. Joel refused.

The next morning the battlefield was littered with more than 400 Viet Cong bodies. Nearly 50 Americans were dead. Many more were wounded. Joel moved about the battlefield to search for the wounded and recover the dead. He finally collapsed. According to Time magazine: “Joel recalls looking at himself: hands encrusted with blood to the wrists, legs thick with edema and dirty bandages. He lay under a tree and cried for the first time since he was a boy in Winston-Salem.”

An officer found Joel and ordered him to the rear for treatment. His comrades, stunned by his display of courage, compassion and determination, nominated him for the Medal of Honor.

President Lyndon B. Johnson presented him with the medal on March 9, 1967. Joel was the first living Black American to receive the award in combat since the 1898 Spanish-American War and the first medic to get it in Vietnam. In 1984, at age 55, Joel died of complications from diabetes. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. V

Doug Sterner, an Army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam, is curator of the Military Times Hall of Valor database of U.S. valor awards.

This interview appeared in the October 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine.