As the Communist Khmer Rouge overran Cambodia, a former CIA pilot pulled off a desperate escape.

Flying for Air America Inc., an airline secretly owned by the CIA in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War, had been the most fulfilling nine years of my life. From 1964 to 1973, I had been based in Saigon and Vientiane, Laos, flying cargo and making airdrops of supplies to friendly locals in hostile territory.

I left it in September 1973 when Air America’s Vientiane base closed. I joined my family who had been living in New Zealand and easily landed a couple of unstimulating jobs, flying tourists over a volcano crater and looking for smoke or lightning strikes in the forests.

After a year of that drudgery, I needed a fix. I was filled with intermingled relief and ecstasy when I received a call from former Air America colleague Pete Snyder (not his real name, which has been changed to protect his privacy), the chief pilot in Cambodia for airline Tri-9. He offered me a job flying Convair 440s, essentially Convair’s version of the venerable DC-3 propeller-driven passenger and cargo plane. I began working for Tri-9 in December 1974.

I was initially based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital. Flying in Cambodia resembled nothing that occurred anywhere in the world of regulated aviation. It was a panic operation, a conglomerate with a wild bunch of pilots and planes—different airlines, but the same uniforms. Anyone with a pilot’s license flew for whatever airline happened to have a flight ready to leave. The crews operated in much the same way as sailors hanging out at a port looking for work on a freighter.

Many of the planes were owned by trucking companies that no longer had safe overland passage because of the Communist Khmer Rouge insurgents overrunning the country. The attackers regularly shot at planes, and as a result most aircraft were adorned with flattened beer cans that had been pop-riveted onto their fuselages for emergency repairs. My narrowest escape occurred when a .50-caliber round went through the wing and fuselage but missed the fuel selector valve by just an inch.

The Khmer Rouge had been fighting Cambodia’s Western-backed government of anti-communist President Lon Nol for years. Lon Nol fled into exile on April 1, 1975, and on April 17 Khmer Rouge troops entered Phnom Penh. The city initially met them with celebrations. Since the civil war was over and Americans were out of the country, order would finally be restored, people thought.

Within hours, however, Phnom Penh’s population was rounded up and ordered to leave for resettlement in the countryside, where former urbanites became workers in a primitive agricultural society to serve the “common good.” People were starved and forced to work endlessly. Families were separated. Many Cambodians died from disease, torture or execution. The new regime, under leader Pol Pot, was a ruthless horror show. Although there are no definitive statistics, it is estimated that the Khmer Rouge killed between 1.5 million and 2 million people, at least a quarter of Cambodia’s population.

I had left Phnom Penh in February 1975 and moved to Kompong Som, on the southwestern coast, roughly 150 miles from the capital, to fly rice in a Convair 440 for Angkor Wat Airlines, named after Cambodia’s majestic Buddhist temple complex built in the 12th century. Kompong Som was a white sandy beach town that might have passed for a trendy resort, except that the nightly entertainment was watching firefights with the Khmer Rouge in the distance.

Thursday, April 17, 1975, began for me at 6 a.m. The noise of the cook slamming the screen door in the kitchen across the courtyard of my beachside motel woke me. From what I could see of the sky outside, it would be a great day for flying. I packed up my stuff in a battered old aluminum suitcase, donned a clean uniform and grabbed a can of PET condensed milk.

On the far side of the courtyard, the cook had set the tables for breakfast. I found a table and punched a hole in the can of milk as my Filipino co-pilot joined me. I had heard the previous day that helicopters had evacuated the U.S. Embassy’s staff in Phnom Penh. By this time, the Khmer Rouge were only about 10 miles from the capital. With the arrival of that news, Pete and I agreed that he would meet me in Kompong Som and we would leave together.

A Douglas DC-3 captain and co-pilot—Chinese men who flew for Khmer Airlines, owned by a trucking company—also sat at our table. They had left the Kompong Som airport much later than we had the past evening, so I asked them if they had seen a Tri-9 Convair come in. Pete might be on it. They reported that only their DC-3 and our Convair 440 were on the ramp when they left the field. They were scheduled to fly a rice shuttle to Phnom Penh after breakfast. I suggested this was not a good time to be going to Phnom Penh. The Khmer Airlines captain was offended. “The Khmer Rouge wouldn’t hurt us—only long-nose Americans,” he said and left.

Not wanting to tip my hand entirely, I told his co-pilot and mine that I was considering getting out. “Good idea, captain,” my co-pilot said.

I told the Khmer Airlines co-pilot he could come along if he wanted but added that I did not want him to tell his captain or anybody else. I feared the Cambodian military might find out about our plans, stop us and turn us over to the Khmer Rouge, an understandable attempt to save their own hides by demonstrating that they were now devoted comrades of the new rulers.

“No, I fly with him,” the loyal co-pilot said, “but if no good, no land, come back go with you.”

“All right,” I agreed, “but if you’re not back by noon, I’m gone.” His jeep showed up, and he left for the airport with his captain.

A half-hour later, a Land Rover sent by Angkor Wat Airlines showed up with the station manager driving and our steward and stewardess in the back. The steward was one of the airline owner’s relatives, and the stewardess performed no function other than being the steward’s girlfriend.

The airport was about 9 miles away. As we started down the hill on the west side of the airfield, we could see our Convair 440, a mural of the Angkor Wat temples on its tail, sitting on the ramp and being loaded. The only other bird on the field was an old Curtiss C-46 military transport resting forlornly in the weeds off the ramp. The Khmer Airlines DC-3 presumably was en route to Phnom Penh.

We had a normal load of pigs, rice and people. Our flight was scheduled to go to Battambang in northwest Cambodia on the first trip and then to Kampong Cham, 75 miles northeast of Phnom Penh. My co-pilot filed a flight plan to Battambang with a Cambodian major and give him his bonjour—a word that in this context translated into “bribe” rather than “good day,” the literal French. Meanwhile, I wandered over to the food stalls lining the edge of the ramp and bought a piece of sugar cane to munch on.

8:05 a.m. Showtime. I began my normal preflight check. We would have to play it cool. If it appeared we were trying to leave the country, we might be stopped by the military or mobbed by people trying to flee before the Khmer Rouge took control.

I told my co-pilot to act like we were going to Battambang. We were going to have to delay takeoff until noon so Pete could join us. I had seen him the previous day in Battambang. He had to fix a flat nose wheel tire but should have been able to get out of there by now.

8:30 a.m. The air stair folded into the fuselage. In the cockpit, the routine went normally. The 2,500 horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-2800 CB16 engine on the right side grumbled to life, belching a cloud of blue-white oil smoke out the augmenter and then settling into a smooth mutter as all 18 cylinders began to warm up. The left engine wasn’t as cooperative, backfiring a few times as the augmenter overheated and beeped. The carburetor on that engine was stuffed and running the mixture too rich. I manually leaned the mixture until there wasn’t any more black smoke coming out.

The temperature and pressures were improving nicely, so I stuck my hand out the window and flipped my thumb sideways, telling the station manager standing to the left front of the plane to remove the chocks from the wheels. After he completed the task, he returned to the left front, snapped a military salute and waved us out of the ramp. What did he think this was, Air Force One, instead of a sick old bird full of pig piss and puke? I returned his salute and advanced the throttles to taxi to the runway.

On the way down the runway, I made a couple of calls on the radio using a plane-to-plane frequency in the blind to determine if there was anyone about to land at the Kompong Som airport, which had no control tower to relay that information. No reply. Where was Pete?

At the end of the runway, I brought the power up and cycled the propellers a couple of times, then advanced the throttles to the field barometric pressure to check the magnetos—ignition devices using rotating magnets to create an electric current. The right engine checked out fine, but when I checked the magneto on the left engine, I slipped the magneto switch to the “off” position and back on. That made the engine backfire.

“What the hell? We better go back to check this thing out,” I said and let out an exaggerated sigh. I then wagged my head in disgust. It was all an act, part of my escape plan, and I was proud of my thespian skills. Back on the ramp, we shut down. Our half-dozen or so passengers deplaned. We didn’t ask if anyone wanted to escape with us because we were afraid someone might divulge our plans to military officials at the airport. I climbed out and asked the station manager for a ladder so I could check the engine. As I climbed the ladder, I continued my deception, bitching about how hard it would be to get two trips in today. I pulled out a couple of spark plugs, went down the ladder, sat on the air stair and began picking some carbon out of the plugs.

9:30 a.m. “Captain, plane coming!” yelled my co-pilot. Barely over the hills to the north was a DC-3 heading our way. The pilot was too low. A few moments passed, and he could be heard coming in at high power, straight and fast. As he came across the threshold of the runway, he jerked the power off and the engines snapped and belched flames from the abuse. The landing was rough and fast. It was the Khmer Airlines DC-3 crew who had breakfast with us. They turned around at the end of the runway and headed to the ramp while still going very fast. The tires squealed, and one wing started up, but the pilot got the plane under control.

The props were still turning when the captain jumped out of the door, yelling for gas. His co-pilot followed, trying to calm him.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“Phnom Penh burning,” the captain answered, agitated. “They shoot at us!” he yelled, like that was something to be surprised about. “We go Bangkok now!”

I grabbed him and hissed, “Shut up, don’t let the military hear you, or we’ll get arrested.”

The passengers on the DC-3 started climbing out. “What are you going to tell the passengers?” I asked.

“We tell them we try again to go Phnom Penh, but go to Bangkok,” the captain said.

“Thai customs will love you,” I said.

“You better go too.”

“Sure, but let’s be a little careful,” I said. “Why don’t you wait in your plane? And I’ll help your co-pilot get gas and clearance.”

The pilot went back to his DC-3.

10 a.m. His co-pilot showed up with the gas truck, and I cornered him. “You know your captain wants to go to Bangkok?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t think that’s a very good idea,” I told the co-pilot. “With passengers, customs there will give you a ration of shit, particularly if some of the passengers don’t want to go to Bangkok.”

“Yes, but what else to do?”

“Go to Sattahip, it’s a Thai Air Force Base, so there aren’t any customs to give you a hard time. If they get nasty, tell them you got lost, or there’s a problem with the plane. If your captain doesn’t like the idea, cold cock the son of a bitch with the fire extinguisher.”

I gave him the frequency for the tower at Sattahip and asked him to monitor 123.9, the frequency used for calls between planes. I would contact him when we got off the ground.

10:30 a.m. The DC-3 was cranking up, and I went back to my Convair 440. The steward asked if the plane was fixed. I said it looked like we would have to unload and test fly it, maybe even have to go somewhere overnight to get it fixed. He might have picked up on my plan because he wanted to go home for some money and clothes.

“Just be back before 11:30,” I said.

The DC-3 started its takeoff roll, slowly breaking ground at the end of the strip and making a gentle turn to a west-southwest heading. The station manager, standing next to me, didn’t say anything about the DC-3 heading in the wrong direction for a flight to Phnom Penh. If he didn’t know before, he knew now that something was up. I asked him to get my plane unloaded so we could fly it. He hesitated and then went to get some workers who took off the rice and pigs.

11 a.m. My plane was now unloaded, and I had replaced the plugs. I had the co-pilot file a clearance for a local test flight. When he came back, he said, “Major nervous, can’t get anybody on the radio.” The major, the officer who received his bonjour earlier, had been trying to reach the military outpost north of the airport to determine if the Khmer Rouge was near.

I didn’t want to risk running the batteries down, so we made a just a few short calls on the cockpit radio, with no luck except on frequency 123.9. The DC-3 answered faintly, reporting everything to be OK, but it had not yet been able to raise Bangkok Center. I gave the pilot my aircraft identification number in case he made contact with Bangkok, so he could tell the crew there that I would be arriving in a couple of hours.

When we climbed back into the plane, I noticed some of the noodle stalls on the edge of the runway were gone and the rest seemed to be hurriedly closing up.

I told the co-pilot to watch the road stretching to the hills in the distance and report if he saw dust coming from the north. I walked to the airport’s makeshift operations office, housed inside a large corrugated metal shipping container called a Conex box. I noticed two more noodle stalls had their front flaps closed and the cart with the sugar cane was being pulled up the road by a little Honda 50cc motorcycle. The only vehicles left were a truck and the major’s jeep.

The major looked up from closing the briefcase that held his bonjour. His face bore the visage of someone who had seen a poisonous snake slithering through the door.

“Going home already?” I asked.

“No more flights today,” he said.

Just for the hell of it, I asked, “When you go, could we ride with you?”

“Not allowed!”

“Never mind, our company car will come back soon. See you tomorrow.” Surely there was an Oscar in my future.

The major had refused me a ride because he didn’t want to be anywhere near a round-eye the Khmer Rouge would think was CIA. He hustled out to the jeep while soldiers from the fuel and oil storage operation climbed into the truck.

11:24 a.m. There were only three of us left at the airport: the station manager, my co-pilot and me.

11:32 a.m. Where was Pete? His wife was in Phnom Penh. She probably would have caught one of the flights to Bangkok since most of the crews knew her, but I was afraid Pete might try to make sure she had gotten out.

11:46 a.m. The station manager was squatted down next to my co-pilot in the shade of the wing. Nobody was talking, just staring to the north where the shimmering heat seemed to magnify the hills in the distance. No dust, no breeze, just eerie quiet.

11:58 a.m. Here came the Land Rover, its driver looking like he was trying to qualify for the Indianapolis 500. He skidded up to the airplane, and the steward and stewardess jumped out.

The steward was panicky. “No people on the road, people all go!” he said.

“Where did they go?” I asked.

“I no know, just go. No good here, we go now?”

“Let’s get this show on the road.”

12:07 p.m. No Pete. Nothing else to do but leave.

Before going up the air stair, I looked into the station manager’s eyes. “We are going to Bangkok. I want you to come too.”

Unflinching, he stared directly back at me and fought to control his emotions. “No sir, I stay. My family. My family Phnom Penh, sir.”

I didn’t reply. What could I have said? We shook hands for the first and last time.

12:11 p.m. We started the engines and broke the stony silence. No chocks to pull since I had already removed them, but the station manager was standing in his place, as usual, looking up at the cockpit, tears tracking down his cheeks. He snapped a salute. My earlier cynicism depleted, I returned his salute, and he waved us out of

the ramp.

At the end of the runway the temperatures and pressures looked good, so I turned around and poured the coal to it. The speed built up, and as we passed the ramp the station manager was still standing there. I realized I didn’t even know his name.

Eighty knots. I came off the nose wheel steering and on to the yoke with my left hand. One hundred knots, rotate.

The plane rises off Cambodian soil for the last time.

****

Pete arrived in Kompong Som after an unsuccessful search for his wife in Phnom Penh. The Khmer Rouge arrested him the next day in the motel room where I had stayed. They marched him to the Thai border and, miraculously, released him. Pete never found his wife. She became one of the victims of the Cambodian holocaust.

The DC-3 crew arrived safely in Sattahip Air Base with little fanfare.

My plane landed in Bangkok, and I was commissioned by the crown prince of Laos to take it to Vientiane and fly for Royal Air Lao. I remained there a few months until advancing Communist Pathet Lao forces necessitated another escape to Thailand, this time by boat.

Southeast Asia was falling down around my knees. It was time to go home to the United States.

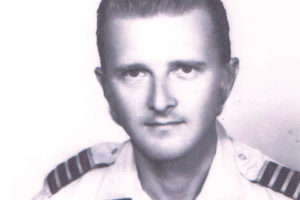

—Neil Hansen travels the country on the speaking circuit, frequently recounting stories about his Air America days to military and veterans’ groups. He lives in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. “The Last Plane Out of Cambodia” is based on a chapter from his book FLIGHT (2019).