Beneath the heatless winter sun, soldiers sprint across hastily constructed pontoon bridges spanning a 55-foot-wide moat, their war cries drowned out by a deafening artillery barrage. Raising improvised bamboo ladders against the walls of the enemy fort, the attackers scramble up even as defenders on the battlements above unleash a shower of hand grenades. The explosives detonate in midair, snapping ladders in half and sending dozens of screaming men to their deaths 45 feet below.

As surviving attackers clamber over the rim of the forbidding wall, the fight degenerates into a series of brutal hand-to-hand melees, with steel broadswords and shorter but no less lethal bayonets drawn for the close-quarters slaughter, as commanders astride Mongolian warhorses ride from section to section, desperately trying to organize their scattered forces atop China’s fabled Great Wall.

Though such images might seem representative of one of the many ancient battles that swirled around China’s most famous fortification, the fight described above actually took place on the chilly morning of Jan. 3, 1933, at the outpost of Shanhaiguan. Long abandoned and left in a state of disrepair since the 1644 Manchu invasion, the obsolescent Great Wall was granted a new lease on life in the 20th century—only this time from the north came not nomadic tribal warriors but the industrialized juggernaut of Japan’s elite Kwantung army.

In a poignant twist of fate the Great Wall, that ancient masterpiece of military fortification, saw its last action at the dawn of World War II in Asia.

The Second Sino-Japanese War—World War II’s often overlooked “missing section of the jigsaw,” as British historian Antony Beevor puts it—took root long before Germany’s 1939 invasion of Poland. Indeed, by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, which gripped the Western world’s attention, China had been embroiled for five years in an even bloodier military conflict with Japan.

By the early 1930s the Kwantung army—garrisoned on Manchuria’s Liaodong Peninsula since shortly after the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War—had evolved into a totalitarian militarist faction within the greater Japanese army that favored expansionism on the Asian mainland. On Sept. 18, 1931, taking advantage of Japan’s turbulent political environment, the Kwantung army independently orchestrated the Mukden Incident (a staged bombing against a Japanese-owned rail line) and the subsequent invasion of Manchuria in a shocking act of insubordination against the Tokyo civilian government’s anti-expansionist policy.

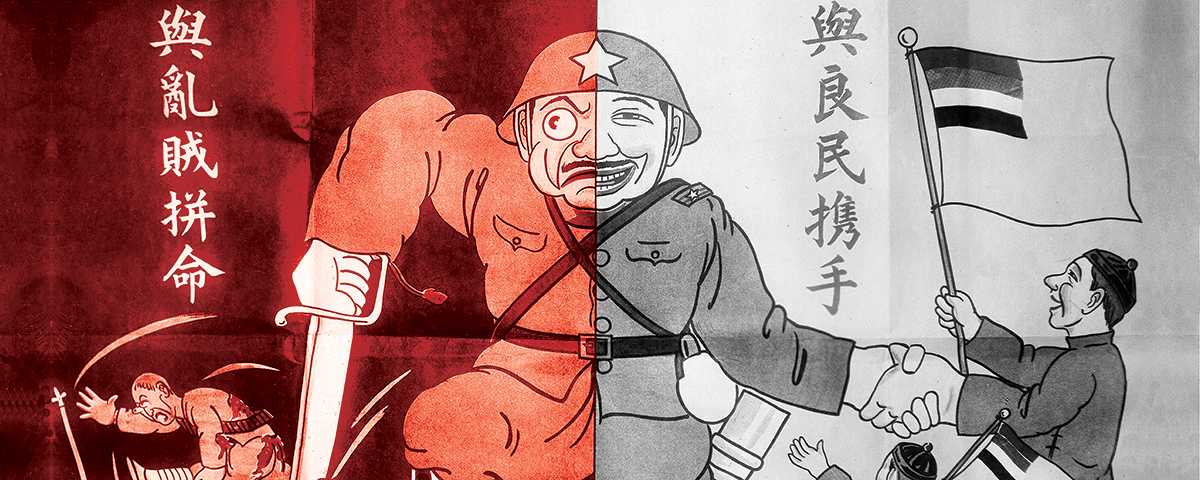

On the Chinese side Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang central government was distracted by its ongoing civil war against Mao Zedong’s Chinese communists, as well as by warlord factionalism within the Kuomintang’s own National Revolutionary Army (NRA). Although an ardent nationalist, Chiang was convinced China was not ready for full-scale war against Japan and adopted the controversial policy of “first internal pacification, then external resistance.” Hence Chinese forces in Manchuria put up virtually no resistance against the Japanese invasion.

Predictably, it wasn’t long before the Kwantung army aspired to further conquests and turned its sights southwest to the Chinese provinces of Hebei and Rehe (pronounced RUH-huh). Rehe—described by a postwar correspondent as “full of tumbling mountains, violent rivers and trouble”—immediately bordered Manchukuo, Japan’s puppet state in conquered Manchuria. Less mountainous Hebei lay south of Rehe, the Great Wall serving as a rough border between the two. Behind the Great Wall lay the bustling metropolises of Beijing (officially Peiping at the time) and Tianjin and then the vast expanse of the North China Plain. After failing to secure Rehe-Hebei as a buffer zone by appealing to a corrupt local warlord, the Japanese decided to take more direct action.

The Kwantung army’s first move was a powerful preliminary attack on the fortified Chinese garrison at Shanhaiguan, on the easternmost end of the main stretch of the Great Wall. Shanhaiguan (“Pass of Mountain and Sea” in traditional Chinese) was named for its strategic position on the narrow corridor leading from Manchuria into China proper. On the evening of Jan. 1, 1933, after staging a grenade attack, the neighboring Japanese garrison commander brazenly labeled the Chinese defenders “terrorists” and ordered them from the pass. When they refused, the Japanese launched a combined arms attack on the garrison the next morning. Compared to their adversaries in the Kwantung army’s 8th Division, the ill-prepared Chinese defenders had little to offer. Other than a handful of Maxim guns and light mortars, their only noteworthy defenses were the centuries-old Ming Dynasty ramparts and watchtowers. Tanks, armored trains, a squadron of Kwantung army bombers and inshore warships from the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 2nd Expeditionary Fleet pummeled China’s ancient fortifications.

Despite a heroic stand by the Chinese defenders, the Shanhaiguan garrison fell after a day of brutal house-to-house fighting. The Japanese had “cracked” the easternmost tip of the Great Wall. But instead of advancing toward Beijing, the Kwantung army shifted its focus westward, away from the Bohai Sea, to the mountains of Rehe.

On February 11 Governor-General Nobuyoshi Muto, commander in chief of the Kwantung army, and his chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Kuniaki Koiso, revealed the plan for Operation Nekka, whose strategic objective was the complete eradication of Chinese military forces in Rehe. Although Japanese units had already broken through the Great Wall at Shanhaiguan, a rash advance toward Beijing along the coastline would expose a long and vulnerable right flank to the Chinese. Although it was doubtful the hard-pressed defenders could or would take advantage of the opening, Muto did not want to take chances. The Kwantung army would first clear out all areas north of the Great Wall in guanwai (“outside the wall,” as the Chinese termed it) before crossing into guannei (“inside the wall”).

Muto launched Operation Nekka on February 23 and within hours received news of Japan’s censure by, and subsequent dramatic walkout from, the League of Nations. The bold offensive called for two divisions and three independent brigades to advance on Rehe along three main southwestward axes, sweeping across the province to deliver a powerful knockout blow to Chengde, the provincial capital just north of the Great Wall. If all went as planned, the nearly 100,000-strong combined force of Kwantung and Manchukuo soldiers would secure the province before Chinese reinforcements arrived.

It was the Chinese themselves who in large part facilitated the dramatic Japanese victory

In fact, the plan went far too well, certainly beyond Muto’s and Koiso’s most optimistic expectations. But it was the Chinese themselves who in large part facilitated the dramatic Japanese victory.

As proven in previous battles, Chiang’s National Revolutionary Army, though poorly trained and equipped, did not lack brave soldiers and capable field commanders. But the NRA command, from the presiding Military Affairs Commission down to the divisional level, was beset by fierce warlord factionalism. Though roughly equal in number to the invading force, the ill-prepared Northeastern Army, commanded by playboy warlord Zhang Xueliang, collapsed like a house of cards before the Japanese onslaught. As Lt. Gen. Yoshikazu Nishi’s 8th Division marched into Chengde on March 4, the dilapidated remains of the Great Wall along the border between Rehe and Hebei provinces became the last line of strategic defense for Beijing, Hebei and the entire North China Plain.

Contrary to popular belief, the Great Wall is not one contiguous fortification spanning China. It is, in fact, an intricate network of defensive walls, forts, trenches, bunkers and natural barriers built, rebuilt and relocated over the centuries by successive Chinese dynasties as their territories expanded or contracted. The majority of the surviving sections of the Great Wall date from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), among the most ardent wall-building dynasties of imperial China. Under continual threat of Mongol, Jurchen and Manchu invasion from the north, the Ming constructed multiple layers of both temporary and permanent walls that ran a remarkable 5,500 miles from the Korean Peninsula west to the Taklamakan Desert.

Although by 1933, almost three centuries after the fall of the Ming Dynasty, the majority of the Great Wall in Rehe-Hebei was in a sorry state of neglect, the vast stretches still standing posed a serious obstacle to any attacker. Following natural contours, the serpentine barrier effectively sealed off most passages through the mountains to the North China Plain, leaving only a handful of heavily fortified passes—Gubeikou on the western edge of Rehe, Xifengkou at the center, Lengkou and Jielingkou on the eastern end—through which an army might maneuver. Even with aircraft and armored cars, Japan’s 20th-century army had no alternative but to assault these fortresses head on with uphill charges against enemy fire from embrasures and arrow slits—just as Chinese engineers had intended when they designed the fortifications centuries earlier.

The Japanese commander immediately ordered all units to disregard their original orders and move south to secure the key passes along the Great Wall before the Chinese could organize effective resistance

While the pace of victory in Rehe took even the Japanese by surprise, Muto knew better than to bask in success. When word reached him on March 4 of the fall of Chengde, the Japanese commander immediately ordered all units to disregard their original orders and move south to secure the key passes along the Great Wall before the Chinese could organize effective resistance and block the route to Beijing. Unfortunately for the Japanese, they had advanced so rapidly that their motorized spearhead was compelled to wait for the bulk of their slowly marching infantry to catch up. That left the Chinese an opening.

After warlord Zhang’s humiliating performance in Rehe and his subsequent resignation, Chiang placed forces in the region under the command of General He Yingqin and a contingent of staff that answered directly to the Chinese chairman. Unlike his ignominious predecessor, He realized the gravity of the situation and immediately ordered the battered Northeastern Army’s remaining divisions to mount an emergency defense centered on the four major Great Wall passes. While anticipating reinforcements from farther south around Beijing-Tianjin, the general would not wait on them.

He understood the Great Wall constituted but a single line of defense with no depth, and while the Chinese had the advantage of terrain, they would be unable to hold in the face of overwhelming Japanese firepower. Thus his plan called for Chinese forces along the Great Wall to delay the Japanese as long as possible, buying time for He to set up a perimeter defense on the outskirts of Beijing and Tianjin. He also requested additional reinforcements from the elite Central Army. Chiang promptly approved. Realizing the extent of the Japanese incursion in Rehe-Hebei, the Chinese commander in chief had called off his thus far unsuccessful Fourth Encirclement Campaign against communist forces in Jiangxi.

Great Wall fortifications at the four key passes feature successive gatehouses that create consecutive barbicans in the narrow pass. Long stretches of the wall descend precipitous slopes to link up with these fortresses, effectively thwarting any possible enemy flanking maneuvers.

When the main force of the Japanese 14th Mixed Brigade and 8th Division finally arrived at Xifengkou on March 10 to launch their assault, the bulk of the reinforcing Chinese 29th Corps was there to meet them. Fierce fighting ensued as the Japanese launched wave after wave of attacks. Under Lt. Gen. Song Zheyuan’s astute command, soldiers of the poorly equipped 29th avoided long-range firefights, which obviously would have given the enemy an advantage. Instead, they let the Japanese approach within 300 feet before rushing out to engage them, thus negating the attackers’ superior firepower by forcing them into close-quarters combat, at which the 29th was highly adept. Many of the Chinese wielded a traditional saber known as the dadao, which proved especially effective in the bloody, medieval-style melees atop the ramparts.

Over two days of fighting the high ground and sections of the Great Wall around the fortified pass changed hands multiple times. More than once the Japanese managed to break into and briefly occupy the first of Xifengkou’s two barbicans, only to be driven back by the resolute Chinese defenders.

On the night of March 11–12 the 29th Corps launched a counteroffensive, led by its best swordsmen and martial artists, who used woodcutters’ trails to infiltrate the Japanese positions. Their superiors specifically instructed the raiders to avoid using firearms and instead rely on the dadao as much as possible. When these elite fighters stumbled on the Japanese 14th Brigade’s artillery positions, they wreaked havoc on the unsuspecting enemy, slaying scores of soldiers in their barracks, destroying artillery pieces with grenades and setting ammunition dumps afire. Seeking to take advantage of the enemy’s disarray in the rear, the main Chinese forces mounted an ultimately unsuccessful frontal assault against Japanese positions.

After ransacking as much as they could, the Chinese raiders vanished into the predawn mist as the disciplined Japanese overcame their initial shock and Chinese casualties began to mount. Though strategically insignificant, the daring raid delivered a blow to the morale of the overconfident Japanese. In its wake Muto grudgingly called off his attack on Xifengkou, gaining the ragtag 29th Corps lasting fame in Chinese military history.

In late March and early April 1933 the Japanese launched probing attacks on Luowenyu, about 35 miles northeast of Xifengkou, but the 29th Corps held firm. At the same time fierce battles raged at the other passes along the Great Wall in Rehe-Hebei, and the results for the Chinese were often less favorable.

After switching hands three times, Lengkou—on the eastern flank of Xifengkou—finally fell to the Kwantung army’s 6th Division on April 11. As soon as the Japanese achieved that significant breakthrough, the entire Chinese defense along the Great Wall began to crumble. Exploiting its success, the 6th advanced farther south toward Qian’an, threatening to encircle Chinese positions at Xifengkou and Jielingkou. On April 13 He ordered defenders at the two passes to retreat, by which time the 29th Corps, originally 15,000 strong, had suffered more than 5,000 casualties.

At Gubeikou the Chinese Central Army’s 17th Corps, which had marched up from southern China, fought a more modern but by no means less savage battle against the spearhead of the Kwantung army’s 8th Division. While the Chinese lost the actual fortification at Gubeikou on March 12, they managed to put up a successful elastic defense to prevent the Japanese from exploiting their breakthrough. The 17th also mounted a number of night raids and counterattacks similar to those conducted by the 29th but using German-supplied Bergmann MP 18 submachine guns instead of cold steel. By May 15 the 17th had suffered more than 4,000 casualties in its fighting retreat toward Miyun and had to be replaced by the Central Army’s newly arrived 26th Corps. By that point Japanese bombers were already circling over Beijing and Tianjin.

Having foreseen the collapse of the Great Wall defenses, He swiftly regrouped his forces for a last-ditch defense at Beijing. By late May Chiang also seemed willing to finally step up to protect his northern metropolis, allotting He one cavalry brigade, two independent artillery regiments and 11 additional infantry divisions from the Central Army, including the German-trained and -equipped 88th Division.

Then the fighting stopped.

With Rehe and northern Hebei firmly in Japanese hands, the Kwantung army had accomplished its goal of securing the southern border of Manchukuo. Facing mounting pressure from both the international community and anti-militarist politicians at home, Muto ultimately decided to bring an end to his grand invasion, halting his forces just shy of Beijing’s city walls. Terms of the Japanese-proposed cease-fire, which became known as the Tanggu Truce, naturally did not favor the Chinese, but Chiang acquiesced regardless, setting the stage for the July 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident and subsequent 1937–45 Second Sino-Japanese War. In the meantime, as the “Rehe Incident” came to its tentative conclusion, a false peace returned.

The 1933 Battle of Rehe was peculiar to early 20th century Asia, where full-scale Westernization was slowly but surely supplanting traditional ways of life. Just like everything else from that turbulent time of revolutionary changes, the military—for a brief moment—also endured a shaky coexistence of the old and the new. As defenders set up their machine guns behind stone battlements, and attackers employed both bamboo siege ladders and aircraft, such surreal scenes of anachronism were unique among the battlefields of World War II. It was in this almost fantastical setting the last major engagement on the Great Wall unfolded, virtually unseen by the rest of the world. MH

Freelance writer Jiaxin Du contributes to both Chinese- and English-language periodicals. For further reading he recommends Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937–1945, by Rana Mitter, and The Second World War, by Antony Beevor, which includes a general account of China’s participation in World War II.