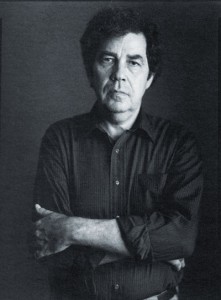

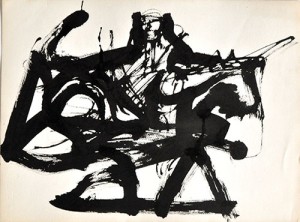

Raymond Spillenger was an artist of the mid-20th-century New York School, an avant-garde community. He and many other New York School artists belonged to a movement that critics dubbed “abstract expressionism” or “action painting” and which with its emphasis on spontaneity took American art into new, exciting realms. Spillenger, who died in 2013, lived and worked outside the traditional marketplace, but his paintings are in the collections of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., and lately his oeuvre and his engagement in a vivid moment in modern American art have been undergoing reconsideration. An exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston, Massachusetts, included his work, and the Neuberger Museum of Art (neuberger.org) in Westchester County, north of New York City, is staging a major Spillenger exhibition that opens September 10, 2016. Son Paul Spillenger has written an essay adapted from a reminiscence published for “Ray Spillenger: Rediscovery of a Black Mountain Painter”, a retrospective of his father’s work now on exhibit at the Black Mountain College Museum+Arts Center in Asheville, North Carolina.

In the winter of 2011, I took my 87-year-old father, Ray Spillenger, to the funeral service for the painter Pat Passlof, whom he’d been close to since 1948, when they attended a legendary summer session at Black Mountain College.

It was a moving experience; Pat had been one of the few artists in Ray’s circle who seemed interested in me when I was a child. I was sad to see my father, who was by then suffering from serious dementia, wonder what he was doing at a Chinese funeral home. When I told him it was Pat’s service, a happy smile spread across his face.

“Oh yeah—Pat!” he said. “How is she?”

I thought of a moment about 10 months earlier, when I’d been living with my father, helping him out in the apartment where my brother and I had grown up and where Ray had lived for more than half a century. One day the phone rang.

“Paul, how is he?” Pat Passlof asked. “Who’s taking care of him? You’ve got to get him a show before he dies,” she said. “You’ve got to do it.”

“Pat, I’ve tried for years, but he doesn’t want it,” I replied, feebly.

“It doesn’t matter what he wants!” Pat was almost yelling. She paused. “He’s the most brilliant unknown painter of his generation.”

When Ray Spillenger died on November 20, 2013, at 89, he was the last of the old crowd to go—at least the last of those I knew, the artists who were a kind of extended family for me when I was a child. With his passing, the door closed on a moment in the history of art, a “scene” he’d inhabited fully, on 10th Street, at the Cedar Tavern, and in the studios and lofts that dotted the Lower East Side.

He was highly thought of by his peers, but my father never became famous and doesn’t figure prominently or at all in most scholarly studies of the period. He’s just beginning to get some much-deserved attention, and to help you understand why that has been so long coming, I’d like to tell you a little about him.

Ray Spillenger grew up in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. When he was eight or nine, his mother started taking him to art classes at the Brooklyn Museum. After graduating from James Madison High School in 1942, he went to the Pratt Institute to study graphic design and in 1943 enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He flew The Hump in Burma, China, and India as pilot of a C-47 transport plane and received the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Corps’ highest honor.

Ray returned to the States in 1946 a changed man. He had, like Odysseus, “seen the cities of many men and known their minds”; suddenly Brooklyn seemed small and provincial, his family obligations suffocating. He was impatient for experience.

After finishing at Pratt in 1948, Ray went for the summer to Black Mountain College—to study art with Mark Tobey, or so he thought. But on the train to Asheville, North Carolina, fellow travelers told him Tobey was ill and that the painting class would be taught by Willem de Kooning. The two guys who filled him in were John Cage and Merce Cunningham.

De Kooning did teach that class, and at Black Mountain he and my father became good friends. Ray also studied with Josef Albers, met Pat Passlof, and did set design for The Ruse of Medusa, a satirical Erik Satie play that Bill and Elaine de Kooning, Cage, Cunningham, and many others worked on.

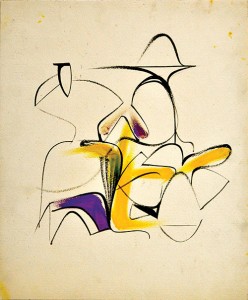

That fall, Ray went to work for Helena Rubinstein as a graphic artist, but his heart wasn’t in it. He was already painting abstract oils, many in the de Kooning style. So when he had an opportunity to study painting in Italy, he grabbed it. He stayed a year and a half.

By early 1951, Ray was back in New York, living and painting on the Lower East Side. He hooked back up with de Kooning and Passlof and through them met other artists—Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Milton Resnick, James Rosati, Reuben Kadish, and many others, famous and not—and was an early member of the Club, that group’s semi-official headquarters.

Ray met Marian Dennison (née Katz) in the early 1950s, and in 1955 they got married; the guest list from their wedding reads like a Who’s Who of Abstract Expressionist painters of the 1950s. A photograph taken at Franz Kline’s studio shows Bill de Kooning, Franz Kline, Vincent Pepi, George Spaventa, Aristodimos Kaldis, and Milton Resnick, along with the smiling newlyweds. I was born a year later, and soon we moved to an apartment on Third Avenue and 10th Street.

This was the world I became conscious in, a street of low-rise walk-ups and lofts, stoops and plate-glass windows, seedy bars, and a liquor store. The Tanager Gallery was there, as was the Camino. The March Gallery, of which my father was a founding member, was in the basement of our building at 95 East 10th.

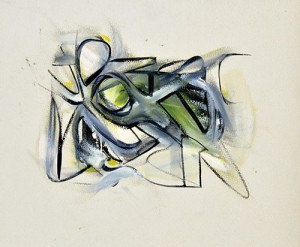

It is hard to imagine the excitement my father must have felt at being part of this movement. He would never have thought of Abstract Expressionism or Action Painting as “styles” or as being driven by some philosophy or credo, but for him—and I suspect for most of the others—it was a movement, defined as much by social reality and attitudes as by ideas about art.

I have faint memories of being taken along to the Cedar (I must have been four or five; who had money for a sitter?) and the smells of beer and cigarettes and the gale of noisy conversation and laughter, and the sweetness of the Shirley Temples with maraschino cherries my parents bought me. Ray and Marian threw Thanksgiving parties in those days, and Kline would be there, and de Kooning, and Passlof, and Resnick, and a crowd of others, and the tiny apartment would fill with an energy I can’t describe—sometimes angry, sometimes physical, often scary, sometimes joyous. It was packed, almost claustrophobic, and always laughter and yelling.

This frantic moment lasted only briefly. Pollock died the year I was born, so I never saw him, and Kline died when I was six. One of my most intense memories of my mother is watching her cry and chain-smoke Salems all day long after she learned Kline was gone. They’d been very close. I named my son after him.

Ray had his lone one-man show at the Great Jones Gallery in 1960. He had pieces in early group shows and exhibited in the March Gallery. That seems to have been about it. By the early 1970s, he had seen his entire social and artistic world fall apart. Pop Art had arrived in America. By 1965 Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol were the darlings of the New York art establishment. Some AbEx painters were wealthy enough to not care; others gave up on art or moved out of the city to raise kids in safer areas with better schools. Ray held on, one of the last of a dying breed, until he couldn’t anymore. By the late 1970s, he had stopped painting altogether. “I thought I could do it all,” he once wrote to me. “I was mistaken.”

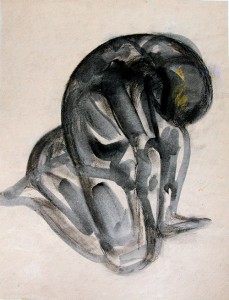

But in the mid-’90s, after 15 years of not painting, long after 10th Street and the New York scene had become unrecognizable to him, Ray started again—not the oil paintings of his youth but smaller, more figurative life drawings and paintings synthesizing much of what he’d done as a young man. In this later work, I see the influences of the Black Mountain artists; the brilliant Renaissance expressions of the human figure he’d seen in Italy; his time in the 10th Street scene of the 1950s and early ’60s; and perhaps even his long hiatus from painting. This was representation informed by the mind, skills, and experience of an abstract painter. He told me he liked what he was doing because he had sloughed off that young man’s albatross—the need to paint the “big painting”—and this had freed him. I believe in this last spurt of work he finally did feel free.

Ray Spillenger continued painting, drawing, and revising for another 15 years or so, until two years before his death, when acute dementia finally made that impossible.

If you had met Ray, you might have thought him somewhat self-effacing, but certainly not meek. He could be very funny, he was incredibly well-read, and he loved baseball. He was notoriously resistant to self-promotion, possibly also a little shy, and averse to the competition and conflict that go along with carving out a “career” as an exhibiting artist. Ray’s reluctance to show puzzled other painters, such as his friends Kline and de Kooning, who both tried to get his work seen. He did not have the flair for the dramatic gesture that Pollock and de Kooning had. But he had the respect and admiration of his contemporaries.

After he died, I went through the 10th Street apartment, gradually discovering a large number of paintings, most of which I had never seen before and which I doubt anyone still living had seen. They were under beds, in closets, behind couches, in boxes and portfolios, or just lying there—170 paintings,dating from the late 1940s through the 1970s and representing distinct periods in Ray’s development as an artist. There were hundreds of works on paper from Ray’s return to art in the 1990s. It was a revelation.

It’s human nature to want to reduce a cultural moment to a few of its prominent participants. But Ray Spillenger’s story is also important, not only for me personally but for those who want a genuine sense of the Abstract Expressionist art scene of the 1950s. My father was a true believer. He valued above all the “act” of painting and felt it beneath his dignity to promote himself or play the gallery game. Partly as a result of this, Ray has remained unknown—a state of affairs I am now working to correct.

In a sense, I have come to know my father for the first time through his life’s work. I invite you to do the same.

—Paul Spillenger

This story was originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.