The first major international traveling exhibit of photographer Sally Mann, which premiered at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., March 4, showcases more than 100 of her photographs, including almost a dozen views of Civil War battlefields, including Antietam, Cold Harbor, the Wilderness, and Fredericksburg. The full scope of the exhibit, Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings, which also includes architectural views, portraits, figure studies, and even family snapshots and keepsakes, explores Mann’s relationship with the American South, particularly its history and heritage as it relates to the Civil War, race, family, and identity.

Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Until May 28, 2018

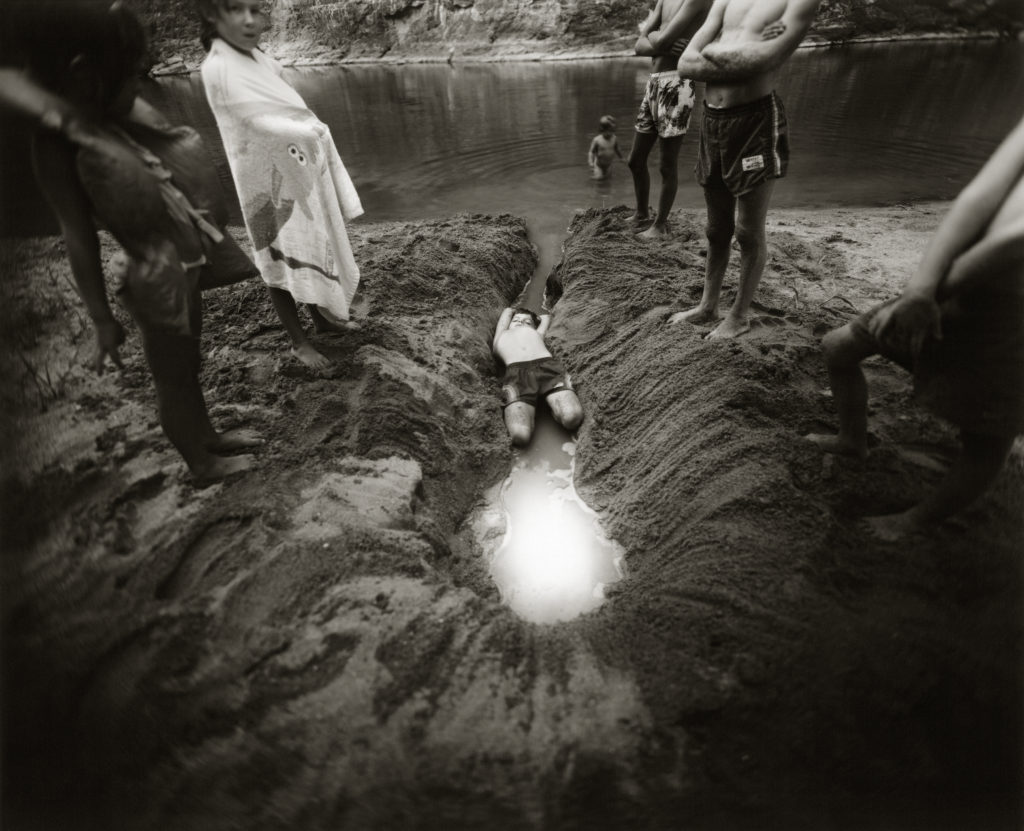

The exhibit is organized into five sections—Family, The Land, Last Measure, Abide with Me, and What Remains. The first section features some of Mann’s most famous images from the 1980s, of her children frolicking, often unclothed, on the family’s Virginia farm. The photos, most of which were shot with a large format 8” x 10” camera in black and white, helped bring Mann to the public stage. Abandoning the popular fine art portrait, Mann sought to capture childhood in all its tenderness and innocence, but without ignoring the messiness, anger, stress, and children’s struggle for individuality.

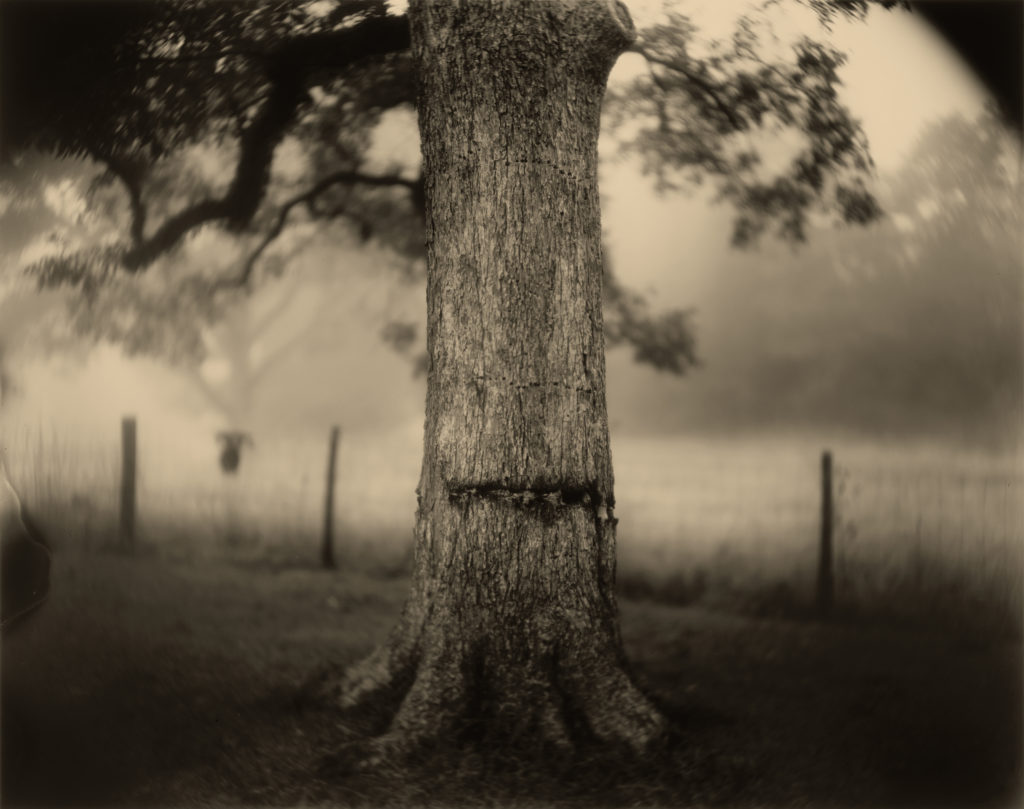

In the 1990s, Mann began to photograph Southern landscapes, showcased in the second section of the exhibit, The Land. She also began to experiment with other forms of photography, including the 19th-century photographic process of making wet plate collodion negatives, used by Civil War photographers such as Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner. Mann particularly embraces the flaws of the process, such as specks of dust or chemical spills, and says she uses them as creative tools.

In 2001, Mann said she began photographing Civil War battlefields to explore the violent histories that lay beneath the often beautiful, serene landscapes. “Does the earth remember? Do these fields, upon which unspeakable carnage occurred, where unknowable numbers of bodies are buried, bear witness in some way?” In Last Measure, the third section of the exhibit, 10 of Mann’s Civil War battlefield images hang in a slightly darkened gallery, the lighting meant to evoke Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation about the miseries of the Civil War, “The heavens are hung in black.”

Mann’s battlefield images are dark, mysterious, and somber. Here she takes full advantage of flaws in the wet plate collodion process to create metaphorical resonance, including specks of dust that create comet or star effects in “Starry Night” on the Antietam Battlefield and streaked dust specks in “Cold Harbor” that fly across the landscape like bullets.

In the fourth section, Abide With Me, Mann specifically explores how race and history shaped the landscapes of the South, but also the people of the South, including her own family. This section includes a series of tintypes of the Great Dismal Swamp, formerly a home to many fugitive slaves, interspersed with large prints of African American men. Representing Mann’s desire to reach across “the seemingly untraversable chasm of race in the American South,” she wanted to address the “rivers of blood” African Americans had poured into the land and their courage displayed during their journeys to escape slavery.

The last section of the exhibit, What Remains, and a final piece of the fourth section, are more autobiographical in nature, including self-portraits of Mann, photos of her husband, and snapshots and scrapbook keepsakes of Virginia “Gee-Gee” Carter, the African American woman who worked for Mann’s family for 50 years and mostly raised her. Haunted by her youthful acceptance of the woman’s presence in her Caucasian home, Mann says she combed through the keepsakes seeking to understand better, “the mystery of it—the blindness and our silence.”

Her full exploration of the history and heritage of the South, both personal and universal, is eloquent and stirring, prompting viewers to admire the beauty of the land and its people, while pondering its provocative past.

“I’ve been coming to terms with the history into which I was born, the people within that history, and the land in which I live, since before I could tie my shoes,” Mann said in 2017. “Now, in the present, there is an urgent cry rising, one that compels me again and again to try to reconcile my love for this place with its brutal history.”