The admiral was livid. José Prudencio Padilla, commander of the Gran Colombian fleet, read the surrender demand from his rival Spanish commander and glared at the officer who had delivered it. The rage in Padilla’s eyes told the messenger that, white flag or not, he would be lucky to survive the next few minutes. Frigate Lieutenant Pablo Llánez wisely kept his mouth shut. Padilla’s assembled staff officers did likewise. Padilla considered shredding the document and shooting the messenger. Instead, he sat down at a small table and began to write.

The Spanish commander who so enraged Padilla, Captain Ángel Laborde y Navarro, had written a message both saccharine and condescending. It concluded with an offer to transport the admiral and his men to territory controlled by Gran Colombia, provided he capitulate and turn over all his vessels and arms. Otherwise, Laborde would come for him. In his reply the admiral told the captain not to bother, for Padilla would come for Laborde. On July 24, 1823, the opposing commanders and their fleets did meet in a brackish strait leading to Lake Maracaibo in what today is the Republic of Venezuela.

Padilla may have assumed the condescending tone in Laborde’s demand stemmed at least in part from the captain’s personal disdain for the admiral. Padilla, after all, was not an Iberian Spaniard, nor even a Creole. Padilla was a pardo, a mulatto of Creole and African ancestry.

Born on March 17, 1774, in La Guajira, a coastal department in the Spanish Viceroyalty of New Granada, José Prudencio Padilla was the son of Andrés Padilla, a humble boatwright, and wife Lucía, a woman of African descent. At age 14 José went to sea with the Spanish navy, rising from cabin boy to boatswain. Captured by the British at the Oct. 21, 1805, Battle of Trafalgar, Padilla spent three years as a prisoner before being released to Spain. On his return home to New Granada he offered his services to the viceroyalty, a predecessor to Simón Bolívar’s visionary Gran Colombia, which included present-day Colombia, Venezuela, mainland Ecuador and Panama, as well as parts of Peru, Brazil and Guyana. By 1811 the young naval officer had joined El Libertador Bolívar’s Spanish American wars of independence. The latter’s vocal opposition to slavery in the emergent republics was doubtless a factor in Padilla’s decision.

In action off Tolú, Colombia, in 1814 Padilla, in command of a small vessel, captured a better-armed royalist corvette and its crew of 170. For his participation in subsequent naval battles, including actions off Venezuela at Los Frailes Archipelago in May 1816 and Carúpano a month later, Padilla was promoted to captain of a frigate. His stock with Bolívar continued to rise with each successive victory. Promoted to brigadier general in 1823, Padilla was given command of the Third Department of what would become the Gran Colombian navy. At the time Bolívar’s patriot forces were on the cusp of victory over royalists in the Venezuelan War of Independence.

Padilla’s royalist adversary, Ángel Laborde y Navarro, was everything the self-made patriot admiral was not. Born into nobility in Cádiz, Spain, on Aug. 2, 1772, Laborde had station, influence and wealth. He was studious and learned, having completed his formal education and begun his naval career as a midshipman by age 19. He saw extensive service during the 1807–14 Peninsular War, first with the Spanish-allied French and then against them when Napoléon installed brother Joseph on the Spanish throne, and Spaniards rose against his rule. Laborde later made two extended cruises to the Philippines, all the while steadily advancing in rank. In short, he was a highly educated professional sailor.

On June 24, 1821, Bolívar scored a decisive victory over royalists at the Battle of Carabobo. Believing the Spanish threat in Venezuela to be over and independence secure, he turned his attention to the south, leaving his native land in the hands of subordinates. But the remnants of the royalist army continued to fight, using both conventional and guerrilla tactics. In September 1822 Spanish forces under Francisco Tomás Morales, captain general of Venezuela, recaptured the port city of Maracaibo (capital of the present-day state of Zulia), on the western shore of the strait leading into the namesake lake. Recognizing the threat the Spanish occupation represented, patriot Generals José Antonio Paez, Rafael Urdaneta and Mariano Montilla marched their armies against Maracaibo but were driven back.

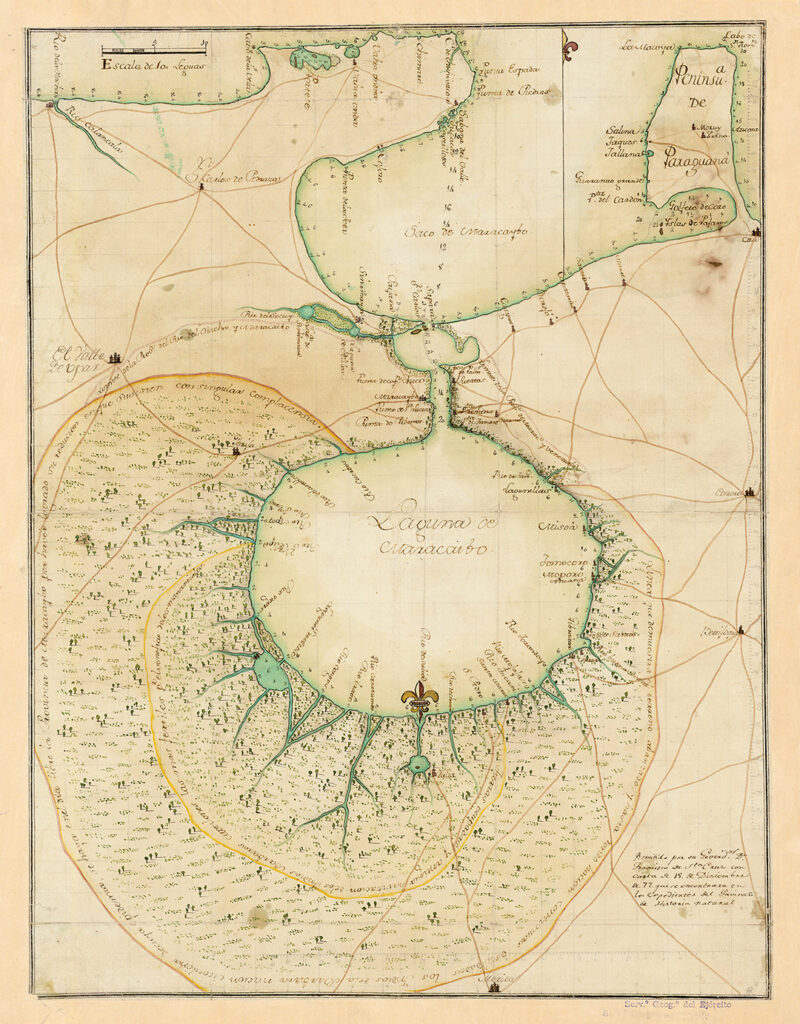

Lake Maracaibo is a tidal bay, or lagoon, connected to the Gulf of Venezuela and the Caribbean Sea beyond by a strait some 30 miles long and scarcely 3 miles wide at its broadest. At 99 miles long and 67 miles wide, the lake itself is slightly more than half the size of Lake Erie, with a maximum depth of 150 feet. Some 135 rivers flow into Lake Maracaibo, which is freshwater in the south and increasingly brackish to the north. While the waters of the lake are generally still, the current through the strait is swift and turbulent.

On the east side of the narrow channel linking the strait and the Gulf of Venezuela is a peninsula, or bar, on which sits Castillo San Carlos de la Barra, a fortress built to control entry into the lake and protect Maracaibo against pirates. Ironically, in 1666 French buccaneers briefly captured Castillo San Carlos, and three years later Welsh privateer Henry Morgan and his men also seized the fortress preparatory to a raid on the port cities of Maracaibo and Gibraltar.

Maracaibo’s strategic importance was immense. All goods from the Andes and Colombia had to pass through the port. Any ship entering the strait from the sea would have to pass under the guns of Castillo San Carlos.

Control of the lake provided the Spanish with a beachhead, allowing the reestablishment of a military presence and resupply of their forces. Their position also flanked Bolívar’s forces, which Morales had pushed inland. If the Spanish could defeat the Gran Colombian armada, Venezuelan independence would be lost yet again. Were Padilla to prevail, however, he could deny Spanish-occupied Maracaibo reinforcements and resupply. Morales’ army would wither on the vine. Whoever commanded the strait controlled the lake and the fate of nascent Venezuela.

Padilla and General Montilla, the commander of patriot land forces, devised a plan to coordinate their efforts and prompt a maritime showdown, thus neutralizing royalist land forces. First, Montilla would attack Maracaibo and lure Morales away from the lake. With Spanish troops thus engaged, the strait would be lightly defended, allowing Padilla’s squadron to enter.

The subsequent battle for Lake Maracaibo was not a single cataclysmic clash but a series of fights—the patriot assault of Maracaibo, the seizure of Castillo San Carlos and its guns, a series of naval skirmishes and the final, decisive engagement.

On March 15, 1823, Padilla sailed north from Cartagena, Colombia, with his small fleet, arriving within sight of Castillo San Carlos on April 5. For several weeks the patriot fleet bided its time in the gulf as the admiral and his staff dithered and debated how best to proceed. Then came word that made their decision for them—Laborde’s Spanish fleet was preparing sail west to Maracaibo’s relief from Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. By then Morales was campaigning against Montilla’s patriot army some 50 miles away and had left Castillo San Carlos woefully underdefended. Padilla resolved to force the bar.

On May 8 the patriot fleet weighed anchor and headed south on a favorable wind. Despite their excellent luck in finding the channel open, four of Padilla’s largest vessels ran aground, shellfire from the fortress making short work of one of them. To refloat the other three, Padilla ordered their ballast and cannons thrown overboard.

While his ploy worked, Padilla realized the ships would be useless without armament. Perhaps taking a page from Captain Morgan, the admiral decided to raid ashore and strip both the port and the castillo of their guns for use on his ships. After sweeping up a Spanish squadron Morales had tasked with defending the lake, the patriot fleet arrived off Maracaibo on June 16. After a daylong bombardment to little effect, Padilla landed a force of 250 infantry and 50 dragoons who fought street by street and house to house until capturing the town and forcing the capitulation of Castillo San Carlos.

Returning to Maracaibo with a 2,500-man Spanish army on June 19—three days too late—Morales found the city looted by Gran Colombian forces and the castillo stripped of its guns and ammunition. After placing some of his own artillery in the fort, there was little for him to do but wait for Laborde.

Meanwhile, having rearmed his fleet with the captured guns, Padilla set about refitting and repairing his ships and training their motley crews for the coming fight.

More than a month had passed since word of Laborde’s imminent departure from Puerto Cabello. His delay was a credit to an unlikely foe. On May 1 a nine-ship Gran Colombian squadron under Commodore John Daniel Danels, an American citizen and Baltimore native, attacked Laborde’s fleet as it left port.

Forming a battle line, the patriot ships traded shots with the royalist fleet at pistol range for two hours. But Danels’ squadron was no match for Laborde’s superior fleet. The patriots lost 60 dead and wounded and 300 captured, including Danels, while the Spanish suffered only 17 wounded. Regardless, the engagement forced Laborde to divert his ships north to Curaçao to refit and repair the damage inflicted by Danels’ stubborn squadron.

Completing repairs in late June, Laborde set out from Curacao on July 4 with a frigate, three corvettes, a brig and some two dozen smaller vessels. Ten days later the Spanish fleet sailed past the guns of Castillo San Carlos into the strait off Maracaibo. En route a windstorm had damaged the rigging of several ships. Laborde would have preferred to make the necessary repairs, but heated exchanges with Morales forced his hand. It was better, the noble-born captain reasoned, to engage one’s enemy at a disadvantage than to be dishonored by claims of cowardice. On July 17 he sent the surrender demand that so enraged Padilla.

On July 22 Laborde, anticipating contact with the Gran Colombian fleet, formed a line of battle to protect Spanish ships stranded in the shallow waters of the strait. A patriot scouting party did appear but was easily repulsed.

Tactical Takeaways

Don’t count chickens.

On defeating a Spanish army at Carabobo on June 24, 1821, Simón Bolívar considered Venezuela free from Spanish rule and took his eyes off the prize.

Bait works on land.

A Gran Colombian army under Mariano Montilla lured Spanish forces away from Maracaibo, leaving it and Castillo San Carlos vulnerable.

Mobility is paramount.

Several Spanish ships became stranded in the shallows, leaving Ángel Laborde little option but to anchor his fleet and fight a defensive battle.

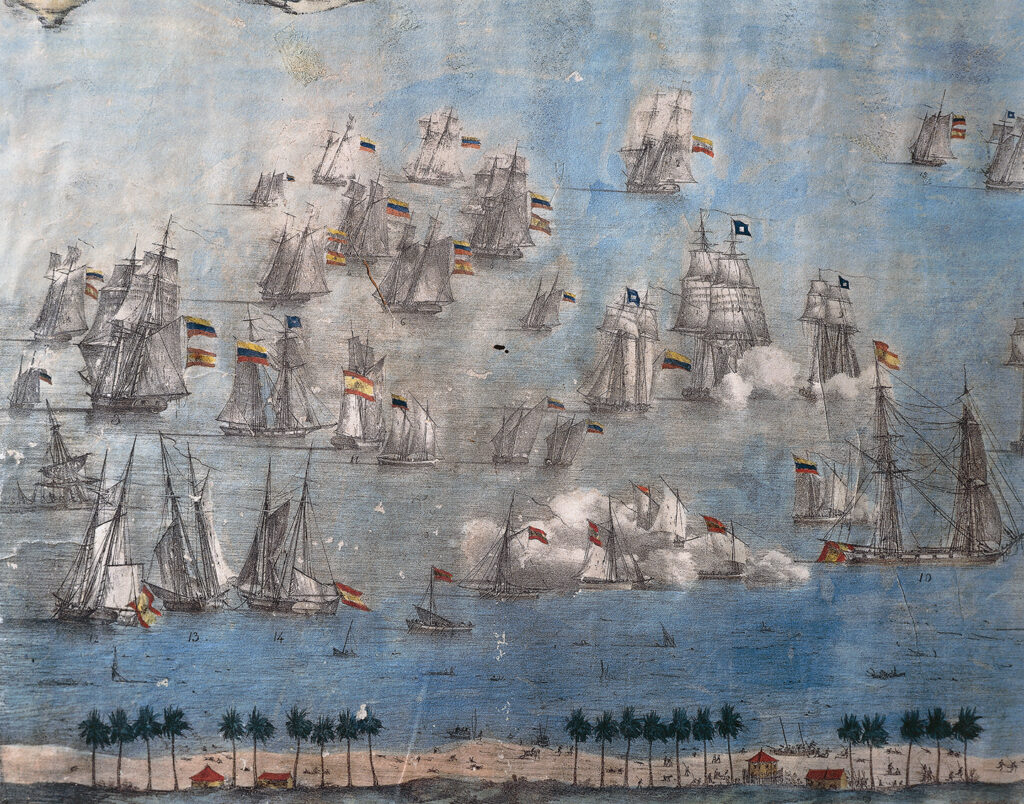

The next day the Gran Colombian fleet suddenly hove into view and closed with the anchored Spanish fleet. A firefight ensued. The patriot ships briefly paralleled the royalist line before turning away and disengaging. Padilla was not yet ready for battle.

Sources differ on the relative strength of the combatant forces, those favoring the Gran Colombian side claiming the Spanish had the more powerful fleet, and vice versa. By most accounts the royalist ships outnumbered those of the patriots by 2-to-1. Sources also differ on the quality of the ships and their crews. Not surprising, Colombian and Venezuelan sources insist the Spanish fleet was far superior, while Spanish sources suggest Laborde’s fleet was in disrepair and manned by shopkeepers, merchants, fishermen and others with no training or experience in naval combat.

Anticipating Padilla would return the next day and believing the damage to some of his ships would make maneuver difficult if not impossible, Laborde ordered his fleet to remain at anchor off the western shore of the strait near Bella Vista, north of Maracaibo, forming a floating fortress. Most of Padilla’s squadron retired to Los Puertos de Altagracia, off the eastern shore of the strait, opposite Bella Vista, while a smaller force anchored farther north.

At dawn on July 24 Padilla ordered his captains to his flagship, the brig Independiente, and gave them final instructions. Not content with that, the admiral visited every ship in the fleet to personally encourage their respective crews.

While Padilla and Montilla had been able to find common ground in the face of a common enemy, Laborde and Morales had not. On several occasions the pair arranged to meet and form a plan, but each time Morales found some excuse to send a junior officer in his stead, thus insulting Laborde. Morales also demanded a decisive naval action despite Laborde’s advice to the contrary. Finally, though Laborde had resolved to assert his position regarding all matters naval, he ultimately swallowed his reservations and committed his fleet. He was simply unwilling to buck Morales, who as captain general of Venezuela was the representative of the Spanish Crown.

That morning Laborde instructed his gunners to carefully target their Gran Colombian counterparts. In the end, it mattered little. With no room or plans to maneuver, the Spanish could only wait for Padilla to make the first move.

Finally, at midafternoon on a favorable wind, Padilla ordered the patriot squadron to attack the royalist fleet head-on. Around 3 p.m. the Gran Colombian ships slipped in among the stationary Spanish vessels so closely that the bowsprits of several ships snapped off at contact. In the ferocious, close-quarters combat that followed, the Gran Colombian ships either destroyed or captured all the Spanish vessels but for three schooners that cut their anchor cables and fled for the shelter of the castillo. Laborde was aboard one of the schooners. Padilla had lost 44 men killed and 119 wounded to Laborde’s 473 killed and wounded and 437 captured. On August 20 Morales evacuated Maracaibo.

The Battle of Lake Maracaibo benefited the cause of Venezuelan independence more than Bolívar could have imagined. Without a fleet to resupply the Spanish forces at Maracaibo, Morales had no option but to capitulate, surrender all warships and installations, and retire to Cuba. Moreover, given the Gran Colombians’ decisive defeat of the Spanish at Lake Maracaibo, international recognition of Venezuela followed. Later that year both the United States and Britain recognized the republic. Not until 1845 did the Spanish government acknowledge Venezuelan independence.

Ironically, the results of the battle had opposite effects on the careers of the winning and losing commanders.

Despite his defeat, Laborde retained the confidence of the Spanish Crown and went on to a distinguished career. It helped that Captain General Morales admitted his error and agreed the captain had justly sought to protect his remaining assets and avoid pitched battle. Laborde served in positions of ever-increasing responsibility. Promoted to brigadier in 1825, he spent the next few years fighting pirates and supporting expeditions tasked with suppressing rebellions in Mexico and other parts of the decaying viceroyalty of New Spain. In 1832, by royal decree, he was appointed minister of the Spanish navy. By the time of his death in Havana from cholera that April the once-disgraced Laborde was much admired. Transported home to Cádiz, his remains were interred in the Pantheon of Illustrious Sailors of San Fernando.

Padilla, whose brilliant victory at Maracaibo assured Venezuelan independence, didn’t fare so well.

Racism had always hounded the dark-skinned admiral, who in his lifetime never received due regard from the largely Creole society he served. He also became enmeshed in the politics of the time, staunchly advocating the rights of the pardos. Despite safeguards in Gran Colombia’s republican constitution of 1821, Bolívar became increasingly authoritarian. Naively, Padilla took sides against his onetime champion in favor of Francisco de Paula Santander, Bolívar’s vice president, who actively solicited the support of the pardos. But the latter had no interest in alienating El Libertador. In 1828 Bolívar declared himself dictator, abolished the office of vice president, crushed the incipient rebellion and had Padilla arrested on a pretext. That September supporters of Santander hatched a plot to assassinate Bolívar, free Padilla and declare the latter their leader. During its botched execution the rebels murdered Padilla’s jailer, a cousin to the father of South American independence.

Though no evidence surfaced that Padilla had conspired to assassinate Bolívar or even knew of the plot, authorities sentenced the hero of Lake Maracaibo to death. He was executed by firing squad on the morning of October 2.

Despite being the ringleader of the rebellion, Santander, a Creole, was ultimately pardoned and exiled. Bolívar had to walk a thin line. Like most Creoles, he feared a revolution by pardos, yet he needed their support. After all, the rank and file of his army largely comprised pardos and Indians. Yet, perhaps calculating he needed the support of Creoles and their wealth more than the fealty of the pardos, Bolívar refused to pardon Padilla. Still, his execution must have bothered El Libertador, who had repeatedly stated his belief in the equality of all men. Indeed, he later expressed regret over the incident and his treatment of Padilla.

A few years after Padilla’s death the Colombian government formally recognized the disgraced admiral as a hero of the revolution and the founder of its navy. In 2000 the government in Caracas also declared Padilla a hero and symbolically interred him in the National Pantheon of Venezuela. Thus in death he finally achieved a measure of respect from those for whom he had fought.

Jerome Long is a former instructor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff Officers’ Course who taught classes on such topics as military intelligence, operational warfare and military history. For further reading he recommends The Venezuelan Navy in the War of Independence, by Hadelis Jiménez López, and Latin America’s Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899, by Robert L. Scheina.

This story appeared in the Autumn 2023 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.