In June 1675 warriors of the Wampanoag sachem, or elected chief, Metacom—known to New England colonists as King Philip—laid siege to the Plymouth Colony town of Swansea, killing settlers, burning homes and igniting a conflict known today as King Philip’s War. Although the murder trial and execution of a trio of Wampanoags by the English had been a pretext for the war, tensions had long been building between the tribe and colonists in Plymouth and adjacent Massachusetts Bay. “The pent-up passions of many years, fanned into flame, were past suppression,” one observer later noted.

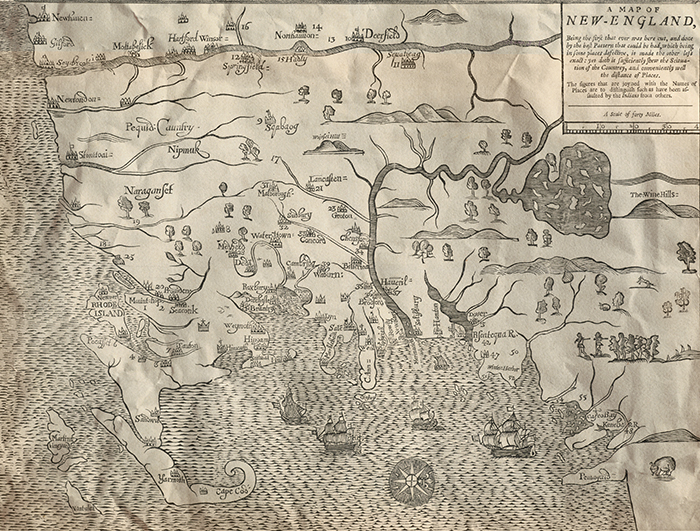

Bordering Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth to the south and west was the tiny colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (united by royal charter in 1663). Of all the English colonies it was the smallest in population, the most divided in sentiment and the least effectively organized for the carrying out of any public policy. Yet it was at this point that Rhode Island, which had been excluded from the military alliance of the United Colonies of New England, was thrust into conflict with the powerful native Narragansetts and their fellow Algonquians the Wampanoags.

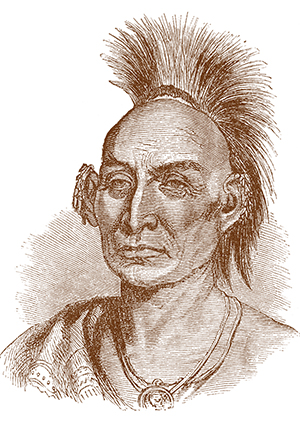

Settlers in Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, as well as those in the United Colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth and Connecticut, all sought to keep the Narragansetts—who occupied most of present-day Rhode Island—neutral in the war and prevent them from joining forces with Metacom. To that end colonial officials, at the urging of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams, held several councils with the Narragansetts and their sachem, Canonchet (or Quanonchet). The Narragansetts also realized war with the English would be a disaster, and Canonchet assured the colonists he had not allied with Metacom.

During the summer of 1675, however, Wampanoag refugees drifted south into Narragansett territory, and Canonchet gave them shelter. In response to what they felt was a violation of Narragansett neutrality, the commissioners of the United Colonies met in Boston in late September 1675. In attendance were several Narragansett sachems, including Canonchet, who agreed to turn over the enemies of the English they were harboring by October 28.

When asked to turn over Indian fugitives from the brewing King Philip’s War, Narragansett sachem Canonchet shot back, ‘No, not a Wampanoag nor the paring of a Wampanoag’s nail’

But when that day arrived, Canonchet didn’t turn over the refugees. When asked if he would surrender them, the sachem reportedly answered, “No, not a Wampanoag nor the paring of a Wampanoag’s nail.” Although the Narragansetts still insisted they had no formal alliance with Metacom, they would not betray their fellow Algonquians to appease the English.

Colonial fears of an alliance between the Wampanoags and Narragansetts became so great that on November 2 the commissioners of the United Colonies took the extraordinary step of authorizing a pre-emptive attack against the Narragansetts to knock them out of the war before they had a chance to join forces with Metacom. Canonchet’s claims of neutrality were not good enough. “In the excited state of mind that existed among both magistrate and people of New England at the time, neutrality was impossible,” wrote George Ellis and John Morris in their 1906 history of the conflict. Rhode Islanders were oblivious to the coming invasion.

The commissioners selected Governor Josiah Winslow of Plymouth to command the colonial army. Massachusetts provided 527 militiamen (under Maj. Samuel Appleton), Connecticut 315 (under Governor Robert Treat) and Plymouth 158 (under Maj. William Bradford). Some 150 allied Mohegan and Pequot warriors from Connecticut accompanied the column. The officers chose “Smith’s Castle,” Richard Smith Jr.’s fortified trading post in Cocumscussoc (present-day Wickford, R.I.), as the rallying point and forward supply base.

While the colonists were preparing for war, the Narragansetts were settling in for the winter. They established their principal settlement in the Great Swamp—thousands of acres of wetlands, open marshes, forest and impenetrable undergrowth roughly a dozen miles southwest of Smith’s Castle. The settlement was huge for an American Indian village. Spanning anywhere from 3 to 6 acres, it held some 500 lodges sheltering the Narragansett warriors, the Wampanoag refugees and thousands of women, children and older men.

The Narragansett palisade had a chink in its armor. As one period chronicler noted after the battle, ‘They had not quite finished the said work’ before the English attacked

Around the settlement the Narragansetts erected a defensive palisade of logs set vertically into the ground with an inner rampart of stacked stone and clay. While the tribe had constructed such fortified villages long before the arrival of English settlers, this one was particularly stout. The Narragansetts built blockhouses at intervals along the perimeter wall to create interlocking fields of fire at every approach. As a final measure they arranged felled trees outside the wall as a defensive abatis to slow the advance of any attacking force. Yet the palisade had a chink in its armor. As one period chronicler noted after the battle, “They had not quite finished the said work” before the English attacked.

The Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth regiments of the colonial army arrived at Smith’s Castle on December 13. Five days later they united with the Connecticut militiamen and their tribal allies at Jireh Bull’s recently ransacked farm in Pettaquamscutt, 7 miles to the south. The winter of 1675–76 was brutal even by New England standards. In Narragansett country 2-foot-deep snow with drifts up to 3 feet covered the ground. When Winslow’s men reached the smoldering ruins of Bull’s farmhouse, they went into bivouac—without tents.

That night Winslow held a council of war with his officers. The army was in a precarious position. They were deep in Narragansett country, short on provisions in the midst of winter, and the men lay exposed to the elements. Had a Narragansett informer with the English name Peter Freeman not betrayed the location of his tribe, the colonists would have had no idea where to find their adversaries. Furthermore, Freeman had agreed to lead the army to the fortified village in the Great Swamp, about 8 miles west of Bull’s homestead. Having come that far, faced with the choice of attacking or retreating, Winslow chose to attack.

Before dawn on Sunday, December 19, the largest army ever assembled by the United Colonies marched off to find the Narragansett stronghold. A Massachusetts company under Capt. Samuel Moseley led the vanguard, followed by the remainder of the Massachusetts regiment. The smaller Connecticut and Plymouth regiments brought up the rear, while the Mohegan and Pequot scouts screened the army’s flanks.

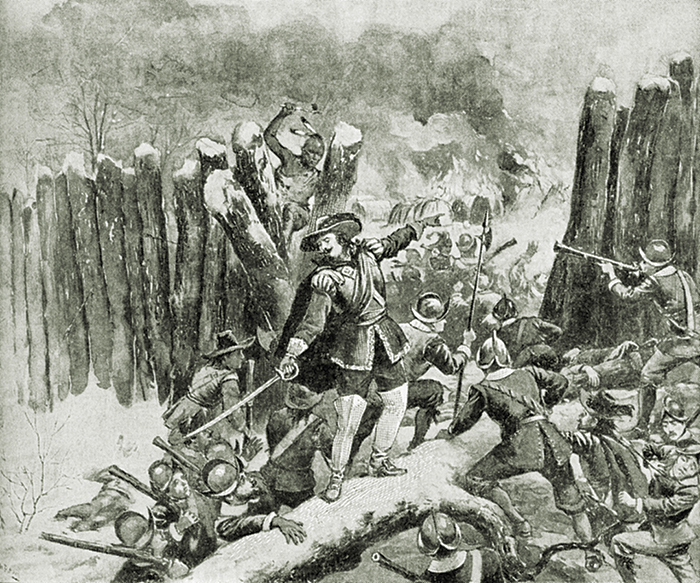

Aware of the approaching English, the Narragansetts initially chose not to contest their advance. Then, shortly after noon, the lead elements of the army were ambushed not far from the Narragansett stronghold. After firing a volley, the warriors retreated inside “ostentatiously” by the principal entrance. But Freeman led the Massachusetts companies around to the right, directly to an unfinished section of the palisade. While a blockhouse guarded that section of the wall, and a large log spanned the gap, no abatis of felled trees obstructed the approach. In another stroke of good fortune for the English, the bitterly cold temperatures had frozen the normally swampy ground solid, granting them good footing over terrain that in warmer temperatures would have been an impassable quagmire.

On spotting the gap, the three Massachusetts companies in the vanguard rushed in without conducting reconnaissance or waiting for the remainder of the army to advance. Their field officers paid a heavy price for such impulsiveness, as on entering the fort, the men were raked by a deadly enfilading fire. Captain Isaac Johnson was slain outside the palisade, while Capt. Nathaniel Davenport entered the fort only to be killed by a withering volley that decimated his company. The two other Massachusetts companies entering the fray were similarly battered.

Stunned by the ferocity of the Narragansett defense, the Massachusetts men poured from the gap in retreat, Capt. Samuel Gardner barely gaining the swamp before being shot dead. Just then Maj. Appleton arrived in their midst. “They run!” he shouted, seeking to rally his men. “They run!” Appleton then led the Massachusetts troops into the breach once more. Again the Narragansetts poured musket fire into the attackers, but the English pressed forward. Driving into the fort, they passed the point where enfilading fire from the blockhouses could reach them. Waiting Connecticut troops, who were taking heavy fire from the walls and blockhouses, then forced the gap, followed by the two Plymouth companies.

The English surged forward, pushing the Narragansetts deeper into the village. The warriors continued to resist, pouring fire on the militiamen from all directions, many attackers taking shots to the back from defenders atop the palisade. The soldiers set fire to a lodge or two, and soon the village was ablaze. As the Narragansett powder supplies ran short, the resistance collapsed.

What followed was not war, but murder.

As Narragansett women, children and older men fled the burning village, the advancing English indiscriminately cut down scores of them with musket and sword. “The shrieks and cries of the women and children, the yelling of the warriors, exhibited a most horrible and appalling scene,” one participant recalled. Survivors fled into the brutally cold winter night. To screen their escape, warriors remained outside the palisade to snipe at any English foolish enough to go in pursuit.

Though the militiamen had won the battle, they were the midst of enemy territory and surrounded by a dangerous foe. Furthermore, they were out of provisions and had not eaten all day. Temperatures were dropping, and the men were exhausted from lack of sleep, having marched all morning before fighting a four-hour battle. Winslow’s aide, Capt. Benjamin Church—an experienced Indian fighter—suggested the army stay the night in the village. That way the men could gather what supplies remained, cook a meal, treat their dozens of wounded and get a good night’s sleep in the shelter of the blockhouses before returning to Smith’s Castle. But a certain doctor accompanying the expedition insisted the wounded be kept moving, or they would grow stiff and be difficult to transport. With few good options, Winslow chose to heed the doctor’s advice and reject Church’s suggestion. Then, despite his men’s desperate need for the food stored in the Narragansett lodges, he ordered the village razed. Not until dusk did he start his depleted army on the long march back to Smith’s Castle.

The journey proved as horrific as Church had predicted. As the soldiers trudged through the deep snowdrifts, the temperatures plummeted further. Despite the doctor’s counsel, nearly two dozen wounded succumbed during the retreat

The journey proved as horrific as Church had predicted. As the soldiers trudged through the deep snowdrifts, the temperatures plummeted further. Despite the doctor’s counsel, nearly two dozen wounded succumbed during the retreat. After an 18-mile forced march the main body of the army finally reached Smith’s Castle at 2 a.m. Winslow and a smaller contingent got turned around in the dark and didn’t arrive for another five hours. But the famished, exhausted soldiers weren’t out of the woods yet, as the castle was out of food.

Soon after the English marched out, Narragansetts began returning to their settlement, only to find the bodies of their kin littering the ground and their food stores largely destroyed. After gathering what supplies and provisions remained, they abandoned the village. From the Great Swamp they traveled north through the freezing cold to seek shelter among friendly tribes in western Massachusetts. Estimates of Narragansett casualties at the Great Swamp Fight vary wildly from a handful to hundreds of warriors killed. “Although badly hurt by the English raid, the Narragansett threat had not been extinguished,” wrote Len Travers and Sheila McIntyre of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. “In fact, the colonists’ actions transformed the formerly neutral survivors into committed enemies.”

At Smith’s Castle the timely arrival of a supply ship sent by the United Colonies spared the army from starvation. Still, English casualties in what was remembered as the Great Swamp Fight were fearful. More than 70 militiamen were either killed immediately or died of their wounds. Another 150 were wounded but survived. Thus nearly one in four Englishmen was a casualty, a testament to the ferocity of the Narragansett defense. Casualties among the officers were particularly appalling. Half of the 14 men commanding militia companies were slain on the field or soon died of their wounds, three each from Massachusetts and Connecticut, and one from Plymouth. The Connecticut regiment had been so severely mauled that it was forced to withdraw from the campaign, over the protests of the other colonies. Winslow did not report Mohegan and Pequot casualties.

Some historians have suggested the Narragansetts purposely left a section of their palisade unfinished, then allowed the English to capture the traitorous Peter Freeman so he might lead them to the killing zone the defenders had established. Such a strategy seems overly complicated and fraught with danger, however. Without Freeman’s help the English wouldn’t have been able to find the enemy settlement, let alone exploit the gap in the palisade. It seems improbable the Narragansetts would prepare such an elaborate fortification to defend their families and food stores only to have the English led to its very gates.

Given the casualties suffered during the Great Swamp Fight, the withdrawal of the Connecticut contingent and the poor condition of survivors, Winslow had no choice but to hold position at Smith’s Castle until the colonies sent sufficient reinforcements for him to resume the offensive. Not until late January 1676 was the army strong enough to retake the field. After leaving Rhode Island, the colonists marched into western Massachusetts in a fruitless search for the Narragansetts, who had withdrawn deep into the wilderness. Again the English nearly starved before Winslow abandoned the campaign.

Meanwhile, the vengeful Narragansetts pursued alliances with other tribes, and by March they were ready to take the offensive. The United Colonies had launched their winter campaign without a formal notice of war, so residents of Rhode Island were unprepared for the coming storm. While rogue Narragansetts had attacked individual settlers, the colony had largely escaped the destruction experienced by Massachusetts and Plymouth. Thanks to the pre-emptive English attack in the Great Swamp, however, the Rhode Island settlers and Narragansetts were soon embroiled in a war they didn’t want.

Retribution was swift and deadly. On March 17 Narragansett warriors entered deserted Warwick, burning the settlement to the ground. Residents of Simsbury, Marlboro and Providence had likewise fled before the Narragansetts struck on March 26 and torched most of their houses, including the Providence home of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams. That same day a force of Narragansett warriors all but annihilated a Plymouth company comprising 63 colonists and 20 Indian allies. Two days later they attacked old Rehoboth (present-day East Providence). By then all but the troops and the most resolute settlers had abandoned Narragansett Bay. The destruction of Rhode Island was complete. Survivors fled to Aquidneck Island, where they lived in constant fear of Indian attack.

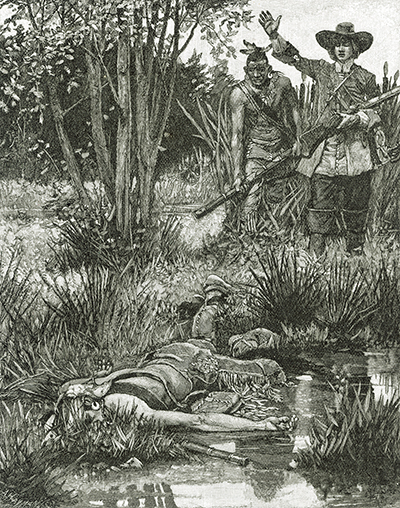

Despite their successes, time was running out for the Narragansetts and Wampanoags. On April 3 Connecticut troops captured Canonchet encamped by a hill on the fringes of present-day Pawtucket, R.I., and transported him to Stonington, Conn. There colonial authorities offered to spare his life if he would order the Narragansetts to end the war. He refused. Officials then turned Canonchet over to his enemies the Pequots and Mohegans, who shot the sachem, quartered and burned his remains, then sent his head to the capital at Hartford as a trophy.

With the arrival of spring colonial armies struck back, burning Indian villages, destroying crops, and killing warriors and noncombatants alike. By midsummer Algonquian resistance had collapsed. On August 12 a company of colonial rangers and Indian allies, led by Winslow’s former aide, Capt. Church, killed Metacom near his headquarters at Mount Hope (in present-day Bristol, R.I.).

The Narragansetts never recovered from King Philip’s War. “The Indians had been practically exterminated,” wrote Ellis and Morris. “Their lands had passed to the whites; a few scantily inhabited villages were all that was left of the mighty tribe of the Narragansetts.…Never again did the southern New England tribes menace the people of these colonies.” As another writer put it, the Narragansetts were “scattered to the winds of Heaven.” Several hundred captive Narragansetts were sold into slavery in the English-held Caribbean and later in Spain. While Rhode Island officially prohibited the enslavement of Indians, officials allowed for the bondage of Narragansetts within its boundaries for a number of years. One small enclave of surrendered Narragansetts remained free in southern Rhode Island, while other individuals settled among the English, often as apprentices. Still other Narragansett survivors drifted west to join tribes in upstate New York. Some eventually migrated west to Brothertown, Wis.

Individual settlers and Rhode Island officials continued to seize Narragansett lands. By 1880 the tribe had lost most of its remaining lands, and the state stripped it of tribal status. The Narragansetts persevered, and in 1978 Rhode Island returned 1,800 acres of tribal land. Five years later the Narragansetts received federal recognition as a tribe.

Neither the Narragansetts nor the settlers of Rhode Island wanted war. Most understood the conflict would bring only devastation to their people. It took an invasion of Rhode Island and Narragansett territory by an uninvited colonial army, followed by a massacre of Narragansetts at the Great Swamp, to spawn the bitter war both sides had avoided. “By the United Colonies [the Narragansetts] were forced to war,” one Rhode Island historian noted, “thereby involving us in such hazards, charges and losses.” Although the colony soon rebounded, the English victory in King Philip’s War forever crushed the power of the Narragansetts. MH

Retired Army officer Douglas L. Gifford specializes in American military history. For further reading he recommends King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict, by Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias; King Philip’s War: Based on the Archives and Records of Massachusetts, Plymouth, Rhode Island and Connecticut and Contemporary Letters and Accounts, by George W. Ellis and John E. Morris; and A Brief History of the Warr With the Indians in New England, by Increase Mather.