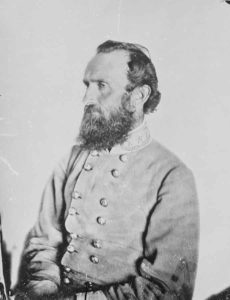

From May 1862 through the Army of Northern Virginia’s bitter end at Appomattox in April 1865, a five-regiment infantry brigade of North Carolina “Tar Heels” fought gallantly in 35 battles and engagements. Known as the Branch-Lane Brigade after its two commanders, Brig. Gens. Lawrence O’Bryan Branch and James H. Lane, the unit consisted of the 7th, 18th, 28th, 33rd, and 37th North Carolina Infantry. The courage, sacrifice, and fighting prowess exhibited on many of the war’s bloodiest battlefields by the brigade’s soldiers—hailed by one of their number, Captain Riddick Gatling Jr. of the 33rd North Carolina, as “these more than immortal men”—has been unfairly overshadowed by a tragic accident on the night of May 2, 1863, at Chancellorsville. In the darkness and confusion following Robert E. Lee’s rout of the Union Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, members of the brigade’s 18th North Carolina mistakenly fired into a party of Confederate officers returning from a nighttime reconnaissance, mortally wounding Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson.

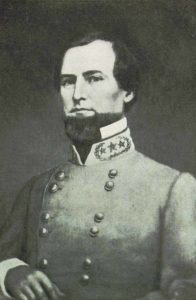

Despite the loss of the irreplaceable Jackson, the Battle of Chancellorsville (April 30-May 6, 1863) is hailed as Lee’s greatest tactical victory, a notable triumph produced by Lee and Jackson’s audacity and Hooker’s timidity and indecision. Defying all conventional wisdom, Lee boldly divided his 60,000 troops—outnumbered more than 2 to 1 by Hooker’s 130,000-man army—and held part of Hooker’s army in front of Fredericksburg with a small force while seizing the tactical initiative to maneuver against the bulk of the Federal army to the west in the Wilderness region. When Hooker inexplicably tarried around Chancellorsville, Lee and Jackson devised an even bolder plan to defeat the Federals. The Branch-Lane Brigade (with Lane in command following Branch’s death at Antietam the previous September), a part of Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Light Division in Jackson’s Corps, soon would be in the thick of the fighting.

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ate on May 1, Confederate cavalry reconnaissance indicated that the Federal right flank was “hanging,” unfortified and unanchored. In light of this intelligence, Lee again chose to divide his command, sending Jackson with 28,000 men, his entire corps, across the front of the Federal army, to attack their exposed lines. The movement left Lee with just 13,000 men, supported by artillery, to distract Hooker and his army while Jackson executed his flanking maneuver.

While Jackson wanted the march to begin at sunrise, May 2, it was 7 a.m. before the lead elements stepped off. The Light Division, bringing up the rear of the column, did not move until 10 a.m. Jackson was spotted riding to the right. When he returned a short time later, Lane’s Brigade moved off, under orders not to cheer Stonewall if he passed. An opening in the woods provided the Federals a glimpse of the Confederates as they marched and gave Union artillery an opportunity to fire on the moving column. From that point on, the Southern regiments moved at the double quick through the opening. Several Federals reported the presence of Jackson’s command, but Hooker believed the Confederate army was retreating toward Gordonsville.

About 2:30 p.m., the head of Jackson’s column turned right on the Orange Turnpike. The men had covered 12 miles but were only 5-6 miles from where they had started a few hours earlier. It took time to deploy two infantry divisions: Brig. Gen. Robert E. Rodes’ in the front, followed by Brig. Gen. Raleigh E. Colston’s, in the thick woods on either side of the turnpike. For many years, the trees had been harvested to make charcoal, and the returning undergrowth was thick, almost impassable in places. Confederate troops lined both sides of the turnpike. Brigadier General William D. Pender’s and Brig. Gen. Henry Heth’s brigades of the Light Division were posted behind Colston, to the north of the road. Lane’s Brigade, just coming up, stayed in column on the turnpike. Federal infantry lay a half mile to the east. While not all of his infantry was up, after checking with Rodes, Jackson gave the order to launch the assault around 5:30 p.m. Bugles sounded, followed soon by a scattering of shots from pickets and the blood-curdling screech of the Rebel Yell. The Confederates had caught the Federal line on the flank and quickly routed an entire corps. Federal soldiers “did run and no mistake about it—but I never blamed them,” wrote Lieutenant Octavius A. Wiggins. “I would have done the same thing and so would you….I reckon the Devil himself would have run with Jackson in his rear.”

Lane’s troops struggled to keep up with the advancing lines of battle. As the main Confederate lines crashed through the woods, Lane’s men double-quicked down the road. Dead and wounded Federal soldiers lay on the road and in the woods. Lewis Battle of the 37th North Carolina said, “Our spirits were so high we could scarcely hold ourselves to the ground, for we could see as we passed along the road at least ten dead Yankees to our one,” including the wreckage of an ill-conceived Federal cavalry charge.

By 7:30 p.m., the Confederate advance began to falter. Rodes’ and Colston’s divisions became intermixed in the terrain and were spent by their march and pursuit of the foe. Rodes called a halt to try reorganizing his command. The sun had set about an hour before, and the moon, just one night shy of full, began to rise, casting eerie shadows throughout the twisted woods. Not only did the two lead divisions stop, but so did Lane, who was following artillery, still standing in the road. Near the brigade stood some earthworks the Federals had built the previous day. Jackson was nearby, attempting to help other officers rally and untangle the Confederate infantry. As Jackson rode by the 18th North Carolina, one of its captains remembered making “that wilderness ring with their cheers” as he passed. Jackson “took off his hat in recognition of their salutation.” During this lull in the fighting, Jackson ordered Hill to bring up his men. He meant to continue the advance and cut off the Federal line of retreat at U.S. Ford over the Rappahannock River. Hill picked Lane’s Brigade to spearhead a rare nighttime attack. He ordered Lane to throw out a regiment as skirmishers and form the rest of the brigade behind them. Once in position, Hill wanted Lane “to push vigorously forward.”

Confederate artillery on the road just ahead of Lane opened fire, drawing a response from a nearby enemy battery. Shell fragments covered the road, and Lane ordered his men to lie down where they were, while he and the rest of his staff dismounted and sought shelter in the woods on the left side of the road.

Hill sent one of his staff officers to inquire why Lane’s Brigade was not deploying as ordered. Lane told the officer he didn’t want to lose his brigade and was “unwilling to attempt to form my line in the dark, under such a fire and in such a woods.” In a postwar letter, Lane wrote, “All old soldiers know how difficult it is to maneuver the bravest troops in the dark under a murderous fire, through scrubby oaks & pine thickets, & over the abatis of the enemy’s abandoned works.”

Lane suggested that Hill order the artillery to stop firing, which would perhaps silence the Federal artillery. The staff officer traversed the fragment-strewn road again, delivering Lane’s response, and Hill ordered the Confederate artillery to desist. Soon thereafter, the enemy counter-battery fire indeed halted as well.

Lane ordered Colonel Clark M. Avery to deploy his 33rd North Carolina as skirmishers. Avery took the regiment and advanced 250 yards to the crest of a hill on its front, fanning out on either side of the Orange Plank Road to provide cover. Lane cautioned Avery not to fire into Rodes’ men, whom Hill’s Division had come to relieve. Avery soon reported no other Confederates to their front. The brigade advanced about 100 yards after the bombardment before deploying to either side of the road, according to one Carolinian. The 7th and the 37th North Carolina filed off to the right, with the 37th’s left anchored on the Plank Road. The 28th and 18th North Carolina filed off to the left, with the right of the 18th likewise still on the road. Portions of Stuart’s Horse Artillery maintained a position on the Plank Road in front of the brigade’s center. “The woods in front of our right was of large oaks with but little undergrowth,” Lane wrote. “[I]n rear of our right there was a pine thicket…to the left of the road there was a dense growth of ‘scrubby oaks’ through which it was almost impossible for troops to move.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]‘All old soldiers know how difficult it is to maneuver the bravest troops in the dark under a murderous fire’ -Brig. Gen. James H. Lane[/quote]

Once Lane formed the brigade, he rode back to the Plank Road, seeking further orders from Hill. Jackson recognized Lane’s voice in the darkness engulfing the Wilderness. “Lane, whom are you looking for?” he called out. “General Hill,” came the reply, “who ordered me to form my line for a night attack, which I have done, and I now wish to know whether I must advance or await further orders…but General, I do not know where General Hill is.” For expediency, Lane requested orders. “Push right ahead, Lane,” Jackson responded, gesturing in the direction of the enemy before moving on. It “was the last time I ever saw him,” Lane later wrote.

With several members of his staff and escort following behind him, Jackson rode down the Orange Plank Road, passing both the 37th and 18th North Carolina. A member of the regiment, Richard Reeves, later claimed that Jackson had ridden up and advised them to “watch and listen and at the least noise, Fire, as it would be the foe. He rode away looking the gallant soldier he was.” A moment later, Hill rode up with his staff, stopping on the Orange Plank Road to converse with Jackson. After urging Hill to push the attack forward, Jackson rode toward the 33rd and the Federal lines, leaving Hill there on the road between the 18th and 37th regiments.

Lee’s Immortals

It is one of history’s sad ironies that the Branch-Lane Brigade probably is most remembered for its tragic “friendly fire” incident that mortally wounded Stonewall Jackson. Although “the death of the beloved Jackson at the hands of the brigade cast a pall over its otherwise stellar history,” few other brigades in the Army of Northern Virginia can lay claim to a combat record which matched, let alone exceeded, that of these “immortal men” from North Carolina. Their staunch service in Robert E. Lee’s army from 1862 until the bitter end at Appomattox, Va., in April 1865 has been favorably compared to that of the more famous Stonewall Brigade or the Union’s splendid Iron Brigade.

In 35 pitched battles and smaller engagements, the Branch-Lane Brigade had 1,197 men killed on the battlefield alone. In addition, nearly 2,000 succumbed to disease, sickness, accidents, or in Union POW camps—bringing the total number who died during the war to 3,151. This represents an astonishing 35 percent mortality rate for the 8,975 North Carolinians who served in the brigade—and, of course, to this staggering number of dead must be added several thousand who suffered nonfatal combat wounds or who endured long-term debilitating effects of disease.

The list of major battles in which the brigade fought reads like an Army of Northern Virginia honor roll: The Seven Days, Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, and Appomattox. At Antietam on September 17, 1862, the brigade—part of Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s “Light Division”—made the brutal march from Harpers Ferry to help prevent Lee’s right wing from being overrun by surging Union forces late in the day. But the cost was high. Killed during the fighting was its commander, Brig. Gen. Lawrence O’Bryan Branch.

Ten months later, under Brig. Gen. James Lane’s lead, the unit took part in perhaps the most famous tactical action of the Civil War—Gettysburg’s “Pickett’s Charge” on July 3, 1863. Lane led the brigade as part of Maj. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s Division in the three-division attack against the Union’s strong defenses on Cemetery Ridge. Of the 1,355 who advanced, 660 fell killed or wounded—nearly half of the brigade’s strength. Among the wounded were three of five regimental commanders, two of whom were subsequently captured.

Fierce fighting during the 1864 Overland Campaign and the nine-month Petersburg siege whittled away the brigade’s numbers. By April 1865, only 738 Tar Heels remained in the ranks.–M.C.H.

Lane rode back along his line to his brigade’s far right. Near 9 p.m., he instructed his colonels to “keep a bright lookout, as we were in front of everything & would soon be ordered forward to make a night attack.” However, as he approached, Lane encountered a dilemma. Nearby Federals were calling out to their enemies, wanting to know whose brigade they were. “General Lane’s” was the reply. “Tell General Lane to come in,” a Federal retorted. Unsatisfied with their inquiry, Lt. Col. Levi Smith of the 128th Pennsylvania stumbled into the 7th North Carolina, bearing a white flag. Smith stated he was simply trying to learn whether the troops in front of him were friends or foes. Much to Smith’s chagrin, Lane refused to let him return to the Federal lines. Instead he sent his brother and aide, Oscar Lane, back to Hill for instructions about what to do with Smith. Meanwhile, Lt. Col. Junius Hill of the 7th North Carolina approached Lane, imploring him not to advance. Hill had heard “noises which satisfied them that troops of some kind were on” the brigade’s right. Lane agreed, and Hill sent Lieutenant James Emack with four men to investigate.

The 33rd was spread out in a line large enough to cover the brigade’s front. Once the line was posted, the regiment’s commanders, Colonel Robert Cowan and Captain Joseph Saunders, returned toward the main line and found General Hill, probably on the Orange Plank Road. The general told the pair their objective was Chancellorsville, that they were “to push on, drive the enemy out of that, then we would have them on the hip.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]‘What are you firing at? Are you trying to kill all my men in front of you? There are no yankees here.’ –Captain Marcellus N. Moorman[/quote]

On the far right of the skirmish line Brig. Gen. Joseph F. Knipe of the 12th Corps’ 1st Division rode into the lines shouting for his commander, Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams. First Sergeant Thomas Cowan of the 33rd North Carolina called out to Knipe, who identified himself as a friend. “[F]riend to which side?” Cowan inquired, to which Knipe answered “to the Union.” “All right,” Cowan responded, stepping back to his company and ordering his men to fire into the area of the voice in the darkness. This brought a quick response from Federal infantry and artillery.

Colonel Thomas J. Purdie positioned the 18th North Carolina to the left of the Orange Plank Road, with the 28th North Carolina to his left. His adjutant, Lt. William McLaurin, claimed later he did not know that the 33rd North Carolina had been deployed on the brigade’s front as skirmishers. Upon hearing noises on his unit’s front, Purdie called for McLaurin, and the two of them walked out into the darkness along the Plank Road. Soon they encountered Colonel Avery and Captain George Sanderlin of the 33rd North Carolina, whereupon a scattering of shots somewhere “two or three hundred yards in our front, to the right side of the road,” led Purdie and McLaurin to hasten back toward the 18th.

The 7th North Carolina had joined the 33rd in blazing away at the Federals, raising a racket that “gave it every semblance of a battle.” Having just captured nearly 200 Federal soldiers not far from their front, they assumed other enemy troops could be nearby. Lane cautioned his men to keep a “bright lookout” ahead. The 37th North Carolina, to the left of the 7th, joined in emptying their muskets toward an unknown foe in the darkness, toward the Orange Plank Road. There Captain Marcellus N. Moorman’s artillery had just limbered up, waiting to be relieved by a fresh battery. Moorman rushed toward the 37th, crying out, “What are you firing at? Are you trying to kill all my men in front of you? There are no Yankees here.” Noah Collins of the 37th North Carolina wrote that he had fired one round and had loaded to fire again when the officers regained control of the men.

The firing rolled on down Lane’s line. In front of the 18th Regiment came the sound of horses in the woods, moving in their direction from the Orange Plank Road. Purdie, still out in front of the regiment, ordered the men to “Fix bayonets; load; prepare for action!” Someone in the regiment yelled “Cavalry,” and the men poured a volley into the woods. “Cease firing! You are firing into our own men,” came a desperate shout through the smoke and darkness. “Who gave that order!” retorted Major John D. Barry of the 18th North Carolina. “It’s a lie! Pour it into them, boys!” With that, sheets of flame from the rifles and muskets leapt out once again into the darkness. John Frink of the 18th North Carolina recalled a stricken horse falling just three feet in front of him. The 28th North Carolina likewise fired a volley into the night.

Nevertheless, the voices crying out in the wilderness had been correct. Unbeknownst to the brigade’s officers and all but a few in the ranks, Stonewall Jackson and A.P. Hill, with their staffs, had ridden through the lines toward the enemy. Some accounts have Jackson taking the Mountain Road and stopping behind the 33rd’s skirmish line, listening to the Federals bringing up reinforcements and strengthening their lines. Other accounts have the group advancing on the Orange Plank Road. Adjutant Spier Whitaker later wrote that Jackson and his staff passed through the lines of the 33rd North Carolina, reconnoitering the Federal position. With the firing on the Confederate right, Jackson’s entourage “came galloping back and across our line to the right of the road to escape the artillery fire.” In all probability, the muskets of the 37th North Carolina drove Jackson and his party from the Orange Plank Road into the woods in front of the 18th North Carolina, who mistook the mounted officers for Federal cavalry. Hill’s staff, closer to the 18th, was decimated by the fire. Though most of Jackson’s staffers survived, the general was struck three times. Amid an outburst of withering small-arms fire, Hill rushed toward the 18th North Carolina, howling, “You have shot my friends! You have destroyed my staff!”

Jackson, meanwhile, lay wounded in the darkness. Hill soon found him and tended his wounds personally while sending orders for an ambulance and a surgeon. Jackson was moved behind the lines. Major W.G. Morris of the 37th North Carolina caught a glimpse of Jackson being carried off. “A party of men carrying a wounded man on a litter halted within ten or fifteen feet of me,” he wrote, “and someone said: ‘General, are you suffering much?’” Early the next morning, Jackson’s ravaged left arm was amputated.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]‘You have shot my friends! You have destroyed my staff!’ –Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill[/quote]

In the wake of the friendly-fire melee that felled Jackson, Hill was wounded, too, from artillery shrapnel across the back of both legs. Hill reportedly stumbled into the lines of the 18th, demanding the regiment’s identity. Hill learned it was the 18th and that it was commanded by Colonel Purdie. When Purdie appeared, Hill chastised him “for firing at a noise.” One member of the regiment, according to McLaurin, brazenly taunted Hill: “A body knows the Yankee army can’t run the ‘Light Division,’ and one little general needn’t try.” Whether Hill heard the taunt is uncertain, but the general sought out Purdie in the next few hours and publicly apologized.

“Our regiment was fully aware of the terrible mistake that they had made, within ten minutes after it happened,” Captain Alfred Tolar of the 18th North Carolina wrote after the war. “Imagine, if you can for no tongue or pen will ever be able to describe the anguish of sorrow that rankled in the bosom of his devoted soldiers as it was whispered from one to another, ‘General Jackson is wounded,’” chronicled a member of the 37th. Lane, still on the right of his brigade dealing with the captured Federals, heard his name being called. He found fellow brigade commander William Dorsey Pender, who advised him of Jackson’s wounding and of the likelihood that it had been caused by Lane’s command.

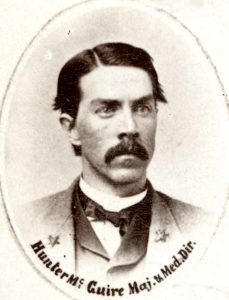

What Really Killed Stonewall Jackson

Stonewall Jackson survived amputation of his wounded left arm the night of May 2-3, 1863, only to die eight days later—purportedly of pneumonia. Eight doctors who cared for Jackson certainly believed so. Over the years, some even claimed that the notorious hypochondriac hastened his own death by deciding to take “cold baths,” accelerating the onset of pneumonia. Yet, according to an article by U.S. Navy officer and physician J.D. Haines in the November 2006 issue of Armchair General, Jackson did not die of pneumonia—he died of an unpreventable pulmonary embolism. Wrote Haines:

Although Dr. Hunter H. McGuire, Jackson’s medical director, and attending physicians agreed that pneumonia was the cause—indeed, it is always given as Jackson’s cause of death—unbiased, modern-day analysis reveals the much more likely cause was pulmonary embolism. Jackson’s so-called pleuro-pneumonia affliction was presumed due to lung contusion incurred during his accidental fall from the litter the night of May 2. However, in any fall less than 3 feet, the subject’s ribs naturally absorb the impact, thereby protecting the lung from serious damage. There also would be obvious external bruising and abrasion in any lung contusion. Yet Jackson’s physicians found no external trauma evidence.

In terminal pneumonia, the clinical course regularly goes from bad to worse in a steady decline. But, in Jackson’s case post-amputation, there were two distinct, sudden episodes of deterioration, separated by a period of apparent recovery—not the expected pneumonia-induced steady decline. His two well-documented episodes of side pain occurred May 3 and May 6-7, in addition to the acute onset of chest/side pain, with accompanying nausea, shortness of breath, extreme fatigue and, perhaps, fever.

These symptoms are consistent with pulmonary emboli, clearly revealing blood clots traveling to the lungs. Among numerous complications following an extremity’s amputation are non-healing of the stump, infection, and thromboembolism—the often-experienced formation of a blood clot within a large vein. According to Dr. McGuire, Jackson’s arm wound appeared to be healing and any infection did not seem to be significant enough to concern his attending doctors.

Today, it is known that an amputee significantly risks venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism. Patient immobilization following amputation can allow blood to pool and clot within veins. However, clots can form in the large veins tied off during the amputation. The veins tying off, termed “ligation,” leads to blood stagnation in the veins, leading to thrombus (blood clot), which can travel to the lungs and kill the patient. Even with today’s advanced technology, as many as half of all pulmonary emboli are undetected. The treatment of thromboembolism employing modern medical procedures is chemical blood thinning agents, unavailable to Jackson.

Given the primitive medical treatment in 1863, Jackson’s post-amputation death could not be prevented; however, examination of his well-documented symptoms reveals Jackson certainly died from thromboembolism—a direct consequence of his arm wound and subsequent amputation, rather than pneumonia long incorrectly presumed. –Jerry Morelock

Upon reaching the 18th, Lane encountered Major Barry, who confessed knowing nothing of Jackson’s and Hill’s riding to the front. Furthermore, “he could not tell friend from foe in the dark & in such a woods, that when the skirmish line fired there was heard the clattering of approaching horseman & the cry of cavalry & that he not only ordered his men to fire, but that he pronounced the cry of friends to be a lie” and kept his men firing. McLaurin added that neither Jackson nor Hill habitually rode to the front.

Some blamed Lane and his Tar Heels for the tragedy played out in the darkness of the Wilderness. “General Lane got scared,” wrote one staff officer in his official report, “fired into our men, and achieved the unenviable reputation of wounding severely Lieutenant-General Jackson and wounding slightly Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill.” After the war, Lane told an early Chancellorsville historian: “In all my intercourse with Genl. A.P. Hill I never heard him, nor have I ever heard any one else censure the 18th regiment for firing under the circumstances.” The debate continues.

Adapted with permission from General Lee’s Immortals: The Battles and Campaigns of the Branch-Lane Brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865, by Michael C. Hardy (Savas Beatie, 2018).

Michael C. Hardy, who in 2010 was named North Caro-lina’s Historian of the Year, is the author of 22 books, including North Carolina Remembers Chancellorsville and Remembering North Carolina’s Confederates.