For several days in May 1862, the green-coated marksmen of the 1st United States Sharp Shooters had made things miserable for the Confederates manning the lines around Yorktown, Virginia. Artillerymen were a favorite target, and unfortunate were the gunners who had to stand up to load their cannons. The sharpshooters were quickly proving that they deserved to be included among the Army of the Potomac’s elite. As proof of that, Brigadier General Fitz-JohnPorter sent a complimentary note to the sharpshooters’ commander, Colonel Hiram Berdan, passing along praise from Major General George B. McClellan: “Your men caused a number of rebels to bite the dust. The Commanding General is glad to find your [regiment] are proving themselves so efficient….”

Berdan had begun organizing his distinctive organization soon after the Federal Army’s defeat at Bull Run in July 1861. A successful inventor and a champion competitive marksman, Berdan offered to organize and train the best shots from the Northern states for service in the Union cause. The U.S. War Department accepted his offer, and when news of the sharpshooter venture and Berdan’s call for marksmen was published in Northern newspapers, recruits from several states traveled to his camp of instruction in Weehawken, N.J.

To prove they were capable, the eager volunteers had to pass a rigorous shooting test—place 10 consecutive shots in a 10-inch bull’s-eye at 200 yards. Newspapermen flocked to Weehawken to see the exhibitions and write accounts about the training. When the sharpshooters moved on to Washington, still greater numbers came to see Berdan, who was commissioned a colonel, and his marksmen. President Abraham Lincoln even visited the camp, accepting an invitation to fire at some targets.

When enough satisfactory recruits were available, the 1st United States Sharp Shooters was mustered in, with four companies from New York, three from Michigan and one each from New Hampshire, Vermont and Wisconsin. Enough men remained to create eight more companies, which were designated the 2nd United States Sharp Shooters. In addition to their designations, their unique uniforms of green trousers, frock coats and forage caps gave the sharpshooters special status, but the men fully recognized the added pressure they would face during battle. “Much is expected of us as Sharp Shooters, and the Commander-in-Chief has more than once stated that he placed great reliance upon Col. Berdan’s corps of riflemen,” noted one sharpshooter. “Depend upon it, more than one rebel General will fall victim to the unerring bullets of our men.”

The 2nd U.S.S.S. was sent to the Fredericksburg area in 1862, but the 1st regiment was given a chance to test its mettle during the Peninsula campaign, General McClellan’s spring 1862 effort to conquer Richmond by marching on the city from the east between the York and James rivers. The men had been promised accurate Sharps breechloading rifles, but they did not receive them in time for the beginning of the campaign. Instead, aside from a few men who carried civilian rifles with telescopic sites, they would carry Colt five-shot revolving rifles into their first real action.

Berdan’s sharpshooters, assigned to General Porter’s 1st Division of the III Corps, were among the first of McClellan’s troops to board transport ships for Fortress Monroe, located at the very tip of the Peninsula. Upon their arrival, Berdan’s men did not have to wait long for action. On March 27, the sharpshooters received word they would lead a reconnaissance toward Big Bethel.

General Porter’s division had been ordered to probe west along two parallel roads toward the Confederate lines, and companies of sharpshooters would lead the way for each of Porter’s wings—with Colonel Berdan and Lt. Col. William Ripley commanding the respective detachments. The soldiers were excited to have an opportunity for action, but as one officer acknowledged, their first brush with the enemy would likely be significant: “Their reputation [could] be made or lost on this reconnaissance.”

Much to the men’s disappointment, other than exchanging shots with some enemy cavalrymen who quickly rode off, little occurred during that initial outing. About noon, Brig. Gen. George Morell sent a staff officer ahead to halt the sharpshooters, followed by orders to return to camp. Although uneventful, this reconnaissance did help Berdan’s men build confidence. Being selected to lead the effort and seeing the enemy cavalry flee at their approach was exhilarating. “It was like a holiday excursion,” recalled one sharpshooter.

In the course of the next week, more Union soldiers arrived at Fortress Monroe, and preparations were made for an advance in force toward the Confederate defenses at Yorktown. On the evening of April 3, the sharpshooters received orders to cook three-days’ rations and prepare to march the following morning. Once again they had been chosen to lead the way. “It was a proud morning for us,” one of the marksmen later recalled, “as we marched past camp after camp, and battery after battery, waiting for us to get ahead and for their places in the column.”

For the first several miles of the advance, the sharpshooters met no resistance; the Confederate cavalry remained just ahead, keeping close watch on the army’s movements. Finally, after marching nearly 20 miles, they spotted a makeshift earthwork near a stream crossing. Berdan ordered out a company as skirmishers, while the rest of the regiment advanced within close supporting distance.

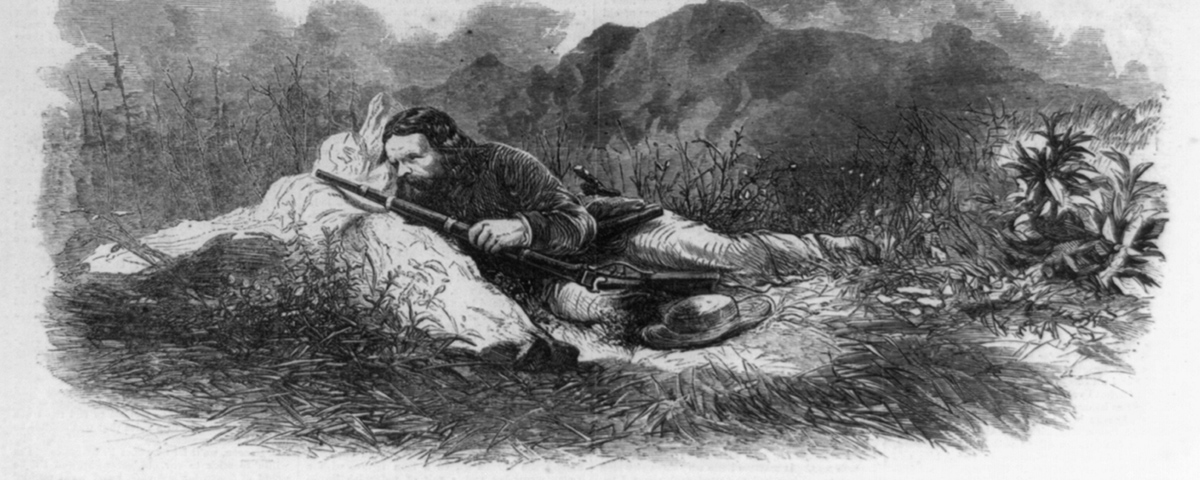

“We immediately deployed as skirmishers and closed in towards the fort,” recalled a sharpshooter in the advance party. “There were only two pieces of artillery there, and as fast as a head would appear over the earthwork our boys would pick him off.” Berdan’s men “took cover behind stumps and other friendly projections [and] the Rebels could not see anything to shoot at.” The Confederates soon deemed it too dangerous to remain unsupported and retired with their artillery pieces.

Berdan’s men pursued the retreating Confederates, capturing some stragglers, and proudly planted their colors on the enemy earthwork. Satisfied with this achievement, and waiting for the rest of the army to catch up, the sharpshooters remained until morning.

Early the next day Berdan’s men pushed forward toward the outer defenses of Yorktown. Advancing through fields and woods in the rain, they made contact with the enemy around 10 a.m. Upon spotting the approaching Union troops, Confederate artillerymen fired some shells in their direction, which sent the troops diving for cover. Once the sharpshooters realized the projectiles were flying harmlessly overhead, however, they got up and pressed on, driving the enemy skirmishers before them.

Nearing the works, Berdan’s men halted to wait for orders and reinforcements. Before long, Porter’s division began arriving, and while the officers were assessing the situation, some Federal batteries were ordered up to shell the Confederate defenses. Companies A and G of the 1st U.S.S.S. were detailed as skirmishers, to protect the cannoneers, while the rest of the regiment was sent to suppress enemy artillery fire.

“We soon came within sight of them, and could plainly see the men loading the guns behind the ramparts,” wrote one sharpshooter. “The two companies with target rifles then took a position where they could command a battery, and picked off many of the gunners, which made them more careful of exposing themselves.”

Companies C and E of the 1st U.S.S.S. were the companies to which the above soldier referred. They were armed with civilian target rifles (as were a few men in other companies). Although heavy and cumbersome, these were extremely accurate weapons. The sharpshooters in Companies C and E took up positions behind a fence, 800 yards from the enemy works, and set their sights and scopes on the artillerymen. Soon men from the other companies, armed with Colt five-shot revolving rifles, joined in firing at the cannoneers.

One sharpshooter in particular made life miserable for the Rebels, an unusual fellow named Truman Head, but better known to his comrades as “California Joe” or “Old Californy.” Head, so the story went, had moved out West after a lover jilted him, then struck it rich in the gold fields. When the war began, the 52-year-old came back East, lied about his age—claiming to be 42—and joined Berdan’s men, carrying a Sharps rifle he had bought with his own money. Since he had no family, Head had left $50,000 in a trust for the care of Union soldiers in case he was killed.

California Joe was well liked and highly respected by his comrades, and his name appears in many sharpshooter accounts of Yorktown. One marksman remembered that slaves who had escaped from the Confederate lines told of a day of slaughter on April 5, when “out of a whole company that worked the guns in a battery near the peach orchard…only 12 were fit for duty the next morning. It was on that occasion that ‘Old Californy’ did such splendid service.”

Confederate artillerymen from other parts of the line soon began targeting Berdan’s men, and the sharpshooters also attracted the attention of increasing numbers of Confederate skirmishers and marksmen, resulting in casualties. When a shot supposedly fired by a Southern soldier ensconced high in a tree killed a private from Berdan’s New Hampshire company, Colonel Ripley took matters into his own hands. Several accounts claim that Ripley advanced out to the location and picked up the dead man’s rifle. Adjusting the scope and taking careful aim at the adversary in the treetop, he pulled the trigger. Whether the colonel actually killed the enemy soldier was unknown, but no more shots came from that tree.

A little after 9 that night, the men of the 1st U.S.S.S. were relieved and retired to the woods in the rear. During their first day of combat, they had suffered three killed and six wounded.

McClellan’s army began examining and probing the enemy defenses at Yorktown. The works seemed strong, and McClellan decided the best course of action would be a siege operation. For the next four weeks the sharpshooters would play an important role in those efforts—picking off enemy artillerymen, dealing with Southern sharpshooters, guarding the fatigue details digging trenches and earthworks, engaging the enemy from the closest line of trenches and bolstering the picket lines.

Although those tasks exposed Berdan’s men to more danger, they realized that being a sharpshooter had its benefits. For one thing, they were exempted from fatigue duty. One of the men noted that made them feel like “privileged characters.”

As the work details continued their efforts, encircling and then moving the line of trenches closer to the enemy’s, the sharpshooters were instructed not to engage the Confederates unless presented with a sure shot. This was especially important when guarding a fatigue detail, as they did not want to draw return fire on the workmen. But whenever they had the opportunity the sharpshooters were to gun down cannoneers, in an effort to suppress enemy artillery fire.

“Gun after gun was silenced and abandoned…every embrasure within range of a thousand yards was silent,” Colonel Ripley proudly wrote of their efforts, adding that Berdan’s men also suppressed Rebel small-arms fire. “The rebel infantry,” he wrote, “which at first responded with a vigorous fire, found that exposure of a head meant grave danger, if not death.”

As Ripley stated, deadly shots from the sharpshooters made manning the Confederate defenses dangerous work. In response, it seems some Southern troops then resorted to a desperate tactic. “They forced their negroes to load their cannon,” an officer in the 1st U.S.S.S. sadly noted. “They shot them if they would not load the cannon, and we shot them if they did.”

Southern officers foolish enough to present themselves in the open also made inviting targets. On one occasion General Porter sent for some of Berdan’s men because the general wanted a Confederate officer on a distant earthwork “killed or driven away from some engineering he was pursuing.” A sharpshooter was assigned to see what he could do. Once the target was pointed out to him, the marksman found a good position, took careful aim and fired. He missed. Adjusting his range, he tried two more shots, missing both times. Guessing that he was firing too low, the marksman increased the angle and discharged his weapon. This time his target fell— reportedly more than 1,000 yards off.

Word of the sharpshooters’ achievements spread, and soon officers all along the line were clamoring for assistance from Berdan’s men. On April 19, Companies A and C, under Major Casper Trepp, were sent to Brig. Gen. William F. Smith’s division, on the left, to deal with some enemy artillery hampering work efforts there. “They have fine fun, being only 250 yards from the Rebels,” noted an envious sharpshooter left behind. “Old ‘Californy’ is in his glory.”

Aside from the larger detachments sent to other units, individual groups of sharpshooters were also deployed to help man picket outposts. A New Jersey soldier wrote, “On each of our posts was stationed one of Berdan’s sharp shooters, who were always on the look out for game, and woe to the rebel who put himself in their way….” Accounts of the sharpshooters’ exploits soon began circulating within the Union camps. “The Sharpshooters have a great name down here now,” boasted one of Berdan’s men to his parents. Through their efforts on the picket line and in silencing the enemy artillery, another proud marksman boasted, “Our regiment won great laurels…and thousands of wonderful stories are told.”

With Berdan’s men causing so many problems, Southern sharpshooters were assigned to handle the menace. Before long, opposing groups of marksmen were dueling each other, and Berdan’s men quickly gained respect for their counterparts. “Soon after we reached Yorktown, we discovered the rebels had Sharp Shooters also,” wrote one 1st U.S.S.S. officer, “and I will give them the credit of having as good shots as I ever saw, and some better than I want to see again.”

On one occasion a detachment of eight sharpshooters drew the attention of a particularly talented Southern marksman. Along the top of their rifle pit, some of Berdan’s men had placed a log and boards with four 3-inch diameter holes for firing. Opposite their position, a Confederate with a telescopic rifle began shooting through each of the openings until a U.S.S.S. sergeant was killed. Berdan’s troops at this location were armed with Colt revolving rifles, which were no match for an enemy with a telescopic rifle.

Frustrated by the situation, Lieutenant J. Smith Brown ran the gantlet of fire to reach a nearby artillery battery. He pointed out the location of the menace to members of Captain Thaddeus Mott’s 3rd New York Artillery battery, and the cannoneers responded. Carefully sighting their piece, they sent a shell toward the sharpshooter’s position that “exploded in his pit, sand bags, timber, gun and man were only a mass of ruins.” Brown noted that this tactic seemed “hardly fair,” but such was war. After that incident Berdan’s men sent back for some comrades carrying target rifles and scopes; four marksmen came up and manned the pit to make sure they would not be outgunned again.

Sharpshooters on both sides earned special respect from their opponents and also engaged in a unique type of competition. One of Berdan’s men recalled that when he peered out of his trench, a ball “flattened the corner of my cap down on my head.” Seeing the man fall to the ground, the enemy marksman thought he had a kill. When the Southerner called out, the Union soldier informed his adversary of the miss, “so that he would not mark down any more Yankees than he was entitled to.”

As one might suspect, Berdan’s men were coveted targets for the enemy. On one occasion when a member of the 1st U.S.S.S. was killed in an advanced rifle pit, some Confederates managed to get to his body. After confiscating his extremely accurate weapon, they left the Yankees a note indicating that they hoped to get more of these guns in the future. That same incident also made the Southern papers, which boasted that a “McClellan Sharpshooter had been picked off by a Kentucky hunter.”

While they were in front of Yorktown, Berdan’s men talked about one particular Confederate marksman more than any other—a black sharpshooter. It seems he occupied a hollow tree more than 1,000 yards in front of their line. Apparently armed with a telescopic rifle, he kept the pickets pinned down with effective fire.

Colonel Berdan received a request to deal with this deadly threat. A member of the 1st U.S.S.S. described how he and a comrade dispatched the enemy marksman:

One of our men in Company G, named Brown, has a small telescopic rifle, weighing only 32½ pounds. He and I were detailed for special duty, this sad duty being to kill a Rebel sharpshooter—a big negro—who had been picking off our men. We waited a long time for a sight at him but he did not show himself. It was getting towards night, when a puff of smoke was seen to rise from a tree near the fort, and a bullet came whistling past our heads. We now arranged our plans. By the aid of a glass I could see his black “mug” peeping from behind a tree. I elevated my sight and fired. It must have come close, for he sprang out. As he did so Brown fired, and “my joker” fell, with a bullet through him. Brown had his sight elevated for fifteen hundred yards!

Using a hollow tree for concealment was just one of the innovative tactics sharpshooters used in confronting each other. When one of Berdan’s men was mortally wounded, the colonel began surveying the enemy line and noticed on a low mound “a long way off” what appeared to be a crow coming into view periodically. Carefully examining the object with a field glass, Berdan watched as the “bird” would periodically appear and disappear. Pointing out the location to Lieutenant William Elmendorf, of Company B, Berdan ordered the lieutenant to take six men to put some holes through the object. Elmendorf’s party advanced under cover of darkness, dug a rifle pit and prepared for sunrise. When the crow emerged the next morning, a sharpshooter sent a bullet just under it, and “what was inside of it, must have stopped a bullet, as it was the last seen of it.”

As the siege at Yorktown progressed, the dangers for the sharpshooters increased because the Federal trenches were continually closing in on the Southerners’ works. Berdan’s men were even nearer the enemy—toward the end of the siege the advanced rifle pits were within 50 yards. Especially because of their close proximity, Berdan’s men were told not to draw fire unnecessarily. “Don’t shoot unless the Rebels open the ball” were the instructions given, but as one sharpshooter noted, the enemy initiated the contest “everyday.” He was also careful to follow his other instructions: “Whenever you see a head, hit it.”

Once General McClellan’s line of entrenchments had closed on the earthworks at Yorktown, the Confederates realized they needed to abandon their defenses. On the morning of May 4, detecting that the enemy works were empty, a commander of a nearby Union regiment requested the honor of entering the defenses. Brigadier General Charles Jameson gave the honor to six sharpshooters, however, saying, “The Sharpshooters have been at the front during the entire siege, and they shall not be displaced now.”

Upon occupying the abandoned position, the Union soldiers heard stories from escaped slaves that further bolstered the reputation of Berdan’s marksmen. One older black man who was inside the fort during the siege later related, “By golly! Stick up a cap, an’ a hole gets in it immediately.”

General Porter complimented the sharpshooters in his official report, saying, “Col. Berdan and Lieut.-Col. Ripley, of the Sharpshooters, deserve great credit throughout the siege for pushing forward the rifle pits close to the enemy’s works, and keeping down the fire of the enemy’s sharpshooters.” Many other officers and men lauded the sharpshooters as well, but all the praise the Union marksmen garnered might well have been summarized in one sentence written by a soldier in New York’s Excelsior Brigade. In a letter home he noted, “Berdan’s Sharp Shooters prove themselves to be one of the most useful organizations of our service.”