Union artillery at the Battle of Stones River shredded Confederate attacks on January 2, 1863

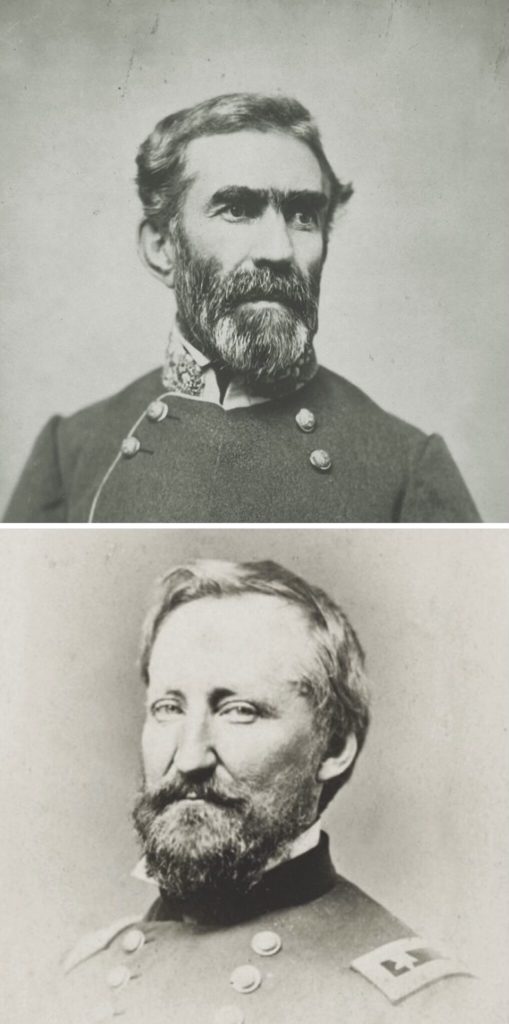

Braxton Bragg seemed satisfied as a bloody day of combat wound down outside Murfreesboro, Tenn., on December 31, 1862. The Army of Tennessee commander was confident that when dawn broke on New Year’s Day, his opponent, Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, would be gone. Although the Confederates could not claim outright victory that first day of the Battle of Stones River, they had enjoyed the advantage after an early morning attack on Rosecrans’ unsuspecting Army of the Cumberland (known at the time as the 14th Army Corps). Rosecrans, Bragg assumed, would pull his army back toward Nashville overnight rather than risk its inevitable annihilation.

Bragg’s contentment on that New Year’s Eve would ultimately cost him the battle. As the general waited to see how Rosecrans would act, he did little to improve his odds, choosing not to draft further plans or to reposition his forces. Rosecrans, however, got busy very quickly. The Union general saw a line of flickering torchlights in the distance during an early morning reconnaissance that he believed signaled another pending Confederate attack. Though he was mistaken, Rosecrans began strengthening his lines. Critically, he also ordered Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden, the Left Wing commander, to reoccupy the high ground above McFadden’s Ford, on the east bank of Stones River.

January 1 would pass with some troop realignment by the opposing forces but no meaningful fighting. Finally, on the afternoon of January 2, Bragg decided to move, ordering Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge to lead a 4 p.m. attack with his division, part of Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s Corps, on the Union left. Bragg believed that an assault launched an hour before sunset, if successful, would thwart any possibility of a Union counterattack. Breckinridge objected, sure the attack was a mistake, but followed orders.

Breckinridge’s troops succeeded in quickly forcing Crittenden’s men off the high ground in front of McFadden’s Ford, but a burst of manmade thunder soon reverberated across the landscape, as 12 Union batteries (57 cannons total) doused the surging Rebels with jagged iron.

By day’s end—in what would prove the most dramatic and effective use of artillery in the Western Theater during the entire war—those smoldering fieldpieces had stopped Breckinridge cold and Rosecrans had managed a crucial victory in Middle Tennessee. Bragg and his army were left to lament a missed golden opportunity.

The clash at Stones River had been building for several months. On October 24, 1862, Rosecrans replaced Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell as commander of the Army of the Ohio, which was renamed the 14th Army Corps, and began efforts to rejuvenate a demoralized army. The Federals had suffered a tactical loss at Perryville, Ky., in early October, and, though Perryville became a strategic victory after Bragg quickly retreated out of Kentucky, it was evident Buell had lost the confidence of his officers and men.

“Old Rosy” succeeded in swiftly revamping the army, but President Abraham Lincoln, the commander in chief, wanted more and pressured the general to engage Bragg’s army, now camped at Murfreesboro, before winter set in. Rosecrans moved first to Nashville in early December. Then, on December 26, he headed south toward Murfreesboro with eight infantry divisions along with Brig. Gen. David S. Stanley’s cavalry and the newly formed Pioneer Brigade of engineers—43,400 men total.

In response, Bragg concentrated his 37,317-man army (five infantry divisions, artillery, and Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry) on a wide front across the Nashville-Murfreesboro Pike and the adjoining Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, protecting susceptible approaches to Murfreesboro. Wheeler’s cavalry performed sporadically during the coming battle itself, but had some success disrupting Rosecrans’ ammunition and food supply lines on December 29-30.

The two army commanders had similar intentions for the morning of December 31, each hoping to launch an attack on his opponent’s right flank. The plan Rosecrans devised called for Brig. Gen. Horatio P. Van Cleve’s 3rd Division in Crittenden’s Left Wing to cross Stones River at McFadden’s Ford first and attack Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s Division. As that attack proceeded, Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s 1st Division was to cross the river above Wayne’s Hill and join the push on Van Cleve’s right, to be followed by Crittenden’s 2nd Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. John M. Palmer.

Bragg moved first, however, and gained the initiative by slamming into Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook’s Right Wing. Coming out of an early morning fog, the Confederate assault soon drove the Union right back about 3½ miles to the turnpike. A desperate defense, spurred by the likes of Brig. Gens. Joshua Sill and Phil Sheridan, and in particular Colonel William B. Hazen, went far in preventing what looked to be a Confederate victory.

With the Federals in disarray, Rosecrans had no choice but to call off his planned attack, recalling Van Cleve’s division across the river. Two of Van Cleve’s brigades, Colonel Samuel Beatty’s and Colonel James Fyffe’s, were sent right to help contest the Confederate envelopment. Colonel Samuel W. Price’s 3rd Brigade remained at McFadden’s Ford, supported by Lieutenant Cortland Livingston’s six-gun 3rd Wisconsin Battery.

The Federals managed to hold on until dark, helped that heavily fatigued soldiers in several Confederate units forced their commanders to call off further attacks. That night, Rosecrans met with his three wing commanders—Crittenden, McCook, and Maj. Gen. George Thomas—in a council of war and decided to keep his army in place, see what developed, bring forward ammunition and supplies, and even consider an attack on the Confederate positions.

Rosecrans’ most important decision came early on January 1 when he instructed Crittenden to reposition his 3rd Division—now commanded by Colonel Beatty, with Van Cleve shelved by a serious foot wound—on the elevated terrain adjacent to McFadden’s Ford. Beatty aligned his brigades in two rows—two in front and one in reserve.

Occupation of this ground, rising about 50 feet above the river, provided Rosecrans with a significant tactical advantage, whether in defense or to launch an attack on Bragg’s right flank, which to that point had not been tested. Bragg recognized, although too late, the advantage of this same high ground, learning to his chagrin the morning of January 2 that Federals were already in place there.

Troops from Palmer’s division were sent to the ford later on January 1 to support Beatty: Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft’s 1st Brigade and Colonel William Grose’s 3rd Brigade. Early the next day, two additional brigades from Brig. Gen. James S. Negley’s 2nd Division, in Thomas’ Center Wing, were sent over: Colonel Timothy R. Stanley’s 2nd Brigade and Colonel John F. Miller’s 3rd Brigade.

The artillery attached to Negley’s and Palmer’s divisions accompanied them to the ground behind McFadden’s Ford. For Negley, there had been 13 guns in three batteries on December 31; he now had six. Palmer was better off. He lost only two of the 14 guns he had, in two batteries, during the fighting December 31.

Captain John Mendenhall, Crittenden’s chief of artillery, positioned these 18 new guns alongside the six-gun 7th Indiana Battery of Van Cleve’s division. Soon, 12 guns of the 26th Pennsylvania and 6th Ohio batteries joined Mendenhall’s artillery, with more batteries on the way.

In the late morning and early afternoon January 2, increased Confederate activity in the direction of McFadden’s Ford was a good indication that an attack was possible. Confederate patrols had engaged Beatty’s skirmish line with increasing frequency and, midafternoon, an infantry battalion-sized patrol supported by artillery probed the Union defenses. Three of Breckinridge’s brigades that had been engaged at the hotly contested Round Forest on December 31 were returned across Stones River to Bragg’s right flank.

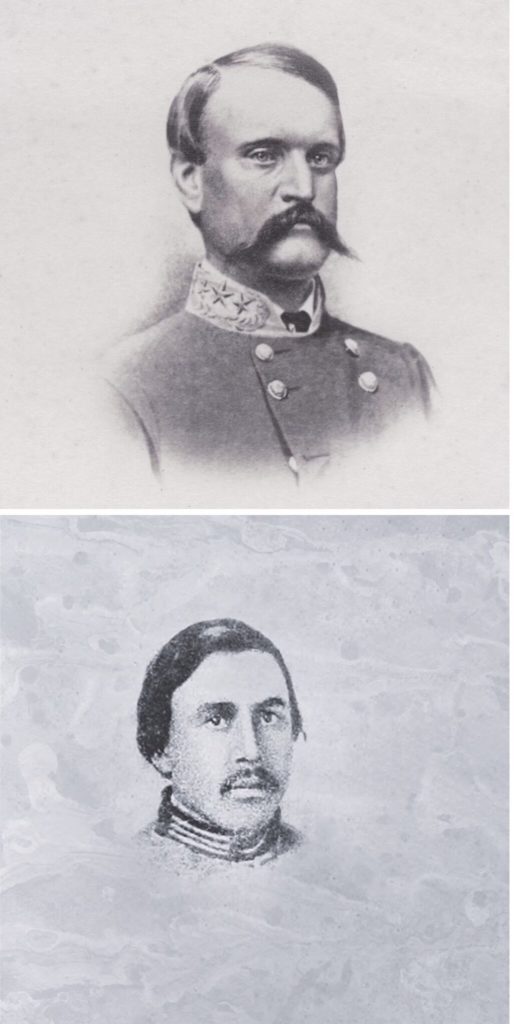

That morning, Breckinridge had ordered skirmishers, supported by artillery, to reconnoiter the Union position on the high ground, with Breckinridge also moving forward for a closer look. Bragg was understandably concerned when Breckinridge reported his observations, realizing the right and center of his army’s position could be subjected to enfilading fire. To Breckinridge’s dismay, Bragg ordered an attack on the Union position. Despite Breckinridge’s protests that the massed Union artillery firing into his flank during an assault would result in heavy casualties, Bragg was not swayed, responding. “I have given you the order to attack the enemy in your front and expect it to be obeyed.”

With no choice, Breckinridge returned to his division to inform his brigade commanders, all of whom shared his outrage. The order was “murderous,” howled Brig. Gen. Roger W. Hanson, who also threatened to go and “kill Bragg.”

At the battle’s onset, Breckinridge’s Division comprised four brigades and an attached brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. John K. Jackson, as well as five batteries. Jackson’s Brigade had joined the three Breckinridge brigades sent to the Round Forest on December 31 but stayed there when those three brigades returned across Stones River. On the afternoon of January 2, Breckinridge had the services of about 5,200 men.

The Confederate attack was set for 4 p.m., just an hour before sunset. Breckinridge hoped to use the short daylight period to his advantage. Commencing the attack and capturing the objective would not provide Federal forces sufficient time to regroup, bring up reserves, and counterattack before dark. This would provide the entire night for Breckinridge and Bragg to reinforce the newly captured high ground and decide on their next move.

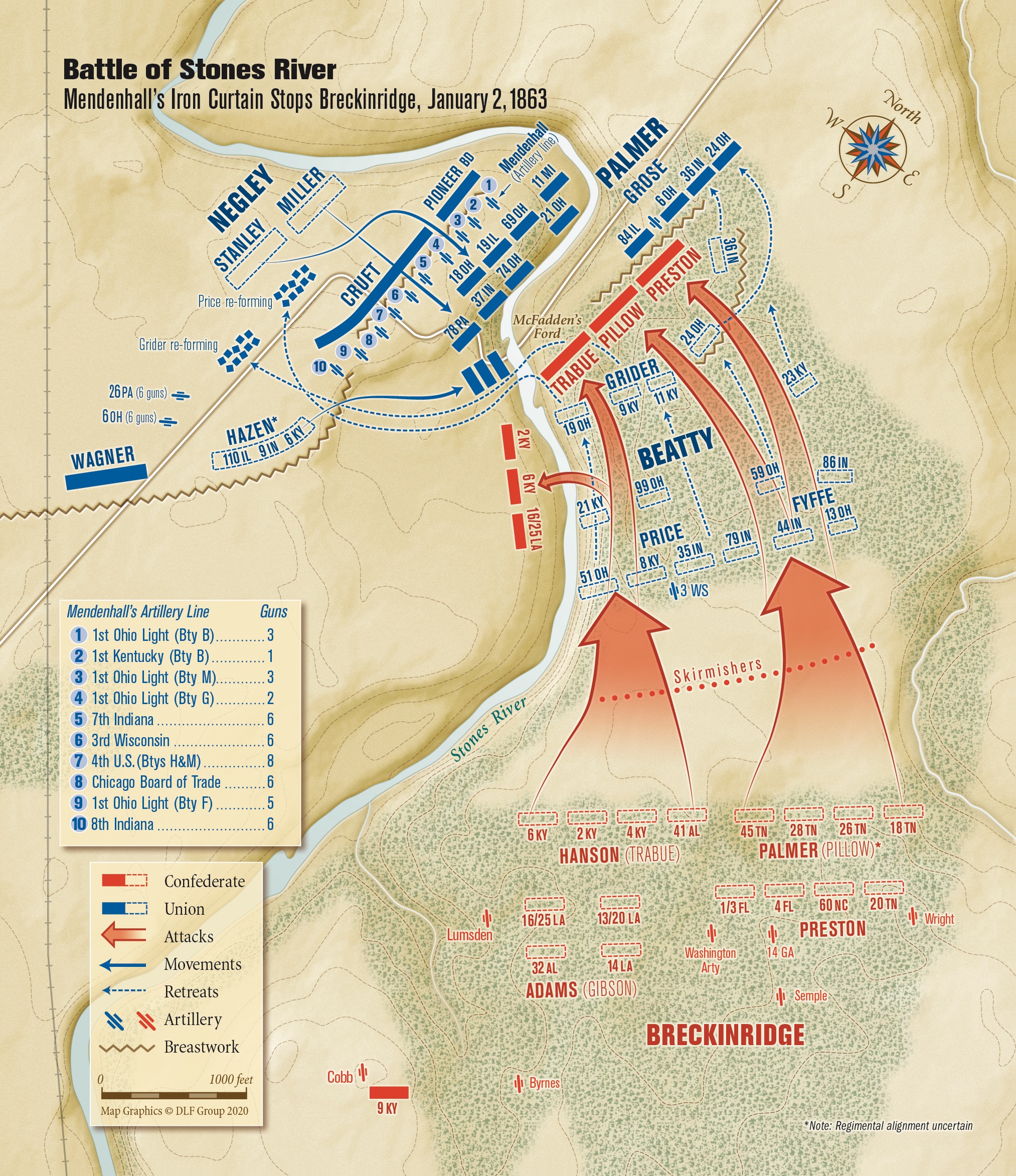

Breckinridge deployed his division with two brigades in front and two in support. On the first line was Hanson’s five-regiment brigade, with Colonel Joseph Palmer’s five-regiment brigade, now commanded by Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, to Hanson’s right. The supporting line featured Brig. Gen. Daniel W. Adams’ three-regiment/one-battalion brigade, commanded by Colonel Randall L. Gibson, on the left, and Brig. Gen. William Preston’s four-regiment brigade on the right.

Supporting the attack were 24 guns of Breckinridge’s divisional artillery. In addition, Bragg ordered Captain Felix H. Robertson to shift his battery and two sections of Captain Henry C. Semple’s Alabama Battery—a total of 10 guns—across the river to join Breckinridge’s attack. Breckinridge and Robertson argued, however, on how to deploy these 34 guns during the attack. Breckinridge wanted all artillery to advance alongside his infantry; Robertson thought the batteries should be held back and join the infantry once the high ground was captured. In the end, Breckinridge’s 24 guns advanced with the infantry and Robertson’s 10 guns waited in place.

As Breckinridge’s leading brigades exited the woods, where they had formed, they came under immediate artillery fire. Hanson’s Brigade marched on the double-quick directly toward Price’s position. Ordered not to fire until they were within 100 yards of the defenders, and then to deliver a single volley and charge with their bayonets, Hanson’s troops moved steadily across the open ground.

Price’s regiments held their fire until Hanson’s men were 60–90 yards away before delivering a devastating volley that temporarily stalled the Confederates. But they soon rallied and continued to advance. The Union position began to crumble as the front-line regiments retreated through those behind, and Price finally ordered his regiments off the high ground. Hanson was mortally wounded in the attack, dying two days later.

On Breckinridge’s right, Pillow’s Brigade hit Fyffe’s position. Because Fyffe’s regiments on the left extended past the Confederate right, they were able to pour flanking fire into Pillow’s men. One of Preston’s regiments, supported by Captain E. Eldridge Wright’s Tennessee Battery, maneuvered to attack Fyffe’s flank, driving those regiments back. The remainder of Preston’s Brigade moved forward with Pillow’s to continue the attack, while Gibson advanced after moving Adams’ Brigade in line with Hanson’s.

In an effort to stop the overwhelming attack, Beatty committed his reserve brigade. Those troops were initially successful, but, once flanked, they too joined in the retreat. After 30 minutes of intense combat, Breckinridge had accomplished his objective: capture of this key terrain east of the river. Darkness was not far off, and though success was within the Confederates’ grasp, what happened next changed everything.

As the Rebel attack proceeded, Captain Mendenhall positioned three more batteries—15 guns total—at the ford, and Livingston’s 3rd Wisconsin Battery returned across the river to add six guns to a formidable Federal artillery line.

That gave Mendenhall the immediate services of 45 guns in 10 batteries, aligned along a 675-yard-wide front. As the terrain on the west bank of Stones River was 10 feet higher than the east, it gave the Union artillery an unobstructed field of fire across the river and the ground beyond.

In the center of Mendenhall’s position was Captain George R. Swallow’s 7th Indiana Battery (six guns). To Swallow’s left were the guns of Negley’s three batteries—Lieutenant Alexander Marshall’s Battery G, 1st Ohio (two guns); Captain Frederick Schultz’s Battery M, 1st Ohio (three guns); and Lieutenant Alban A. Ellsworth’s Battery B, 1st Kentucky (one gun). To the left of Ellsworth were the three guns of Captain William E. Standart’s Battery B, 1st Ohio.

On Swallow’s right was the 3rd Wisconsin (six guns), flanked on its right by Lieutenant Charles C. Parsons’ Batteries H and M, 4th U.S. (eight guns). Captain James H. Stokes’s Chicago Board of Trade Battery (six guns) was on Parsons’ right, alongside Lieutenant Norval Osburn’s Battery F, 1st Ohio (four guns) and Lieutenant George Estep’s 8th Indiana Battery (six guns). Mendenhall also had the support of four infantry brigades, as well as the recently arrived Pioneer Brigade in reserve.

There were 12 additional guns stationed to Estep’s right , belonging to Lieutenant Alanson J. Stevens’s 26th Pennsylvania Battery and Captain Cullen Bradley’s 6th Ohio Battery (six guns each). While the Confederates attacked, these batteries were able to deliver oblique and enfilade fire.

It was 4:30 p.m. Beyond the high ground Breckinridge had captured was a stretch of land featuring several rolling depressions that should have been used to provide protection from Mendenhall’s artillery. Instead of consolidating their gains, however, the Confederate infantry, flush with victory, rushed forward into the Union artillery’s kill zone.

The ground the Rebel infantry crossed in pursuit of the fleeing Federal troops extended roughly 900–1,000 yards. Once they reached the river, the attacking Confederates would be partially protected by a steep slope, which provided some relief from Mendenhall’s guns but did not prevent rifle fire from the infantry supporting the artillery.

As soon as Breckinridge’s men began crossing the open ground, the big Union guns opened fire. Mendenhall, a seasoned, tactically proficient artillery officer, handled his batteries deftly over the next 15-20 minutes. With each gun firing at a rate of two rounds per minute, those 57 guns unleashed 114 rounds for every minute of the attack. The result was a total of 1,710–2,280 rounds that tore apart the compact and rapidly disorganized mass of Confederate infantry.

Lieutenant Edwin P. Thompson of the 6th Kentucky Infantry offered the best description of the Federal cannonade from the Confederate perspective, writing:

The main body…were on the point of dashing wildly into the river, the very earth trembled as with an exploding mine, and a mass of iron hail was hurled upon them. The rushing host had been checked in mid-career, and now staggered back. The artillery bellowed forth such thunder that men were stunned and could not distinguish sounds. There were falling timbers, crashing arms, the whirring of missiles of every description, the bursting of the dreadful shell, the groans of the wounded, and the shouts of the officers, mingled in one horrid din that beggars description. To endeavor to press forward now was folly, to remain was madness, and the order was given to retreat. Some rushed back precipitately, while others walked away with deliberation, and some even slowly and doggedly, as though they scorned the danger or had become indifferent to life….But they paid toll at every step back over that ground which they had just passed with the shout of victors….It was stated by a participant that the time from giving of the command “Charge bayonets” till the Confederates had been driven back was forty-two minutes…in the short space of time mentioned, and chiefly during the last fifteen minutes, Breckinridge’s loss, as stated by himself, was seventeen hundred men—more than thirty-seven per cent.

The sustained Union fire stopped, broke up, and then drove back Breckinridge’s infantry. Negley’s two brigades (Stanley’s and Miller’s), which had been supporting the artillery, counterattacked and drove the Confederates beyond the recently captured higher ground. As dark descended on the battlefield, the key terrain east of the river was again occupied by Union troops.

So, what had gone wrong for Breckinridge, especially after his early success? Three factors were principally involved:

First, the Confederate artillery was poorly handled. Breckinridge had 34 guns available to support his attack: 24 under his control and 10 commanded by Felix Robertson, captain of a battery in Maj. Gen. Jones M. Withers’ Division. Breckinridge and Robertson argued about the employment of the artillery. Breckinridge wanted all of the available artillery to accompany his attack, but Robertson thought such a maneuver would compress the batteries and place them in a dangerous position. He wanted to hold the artillery back until the high ground had been captured before bringing the guns forward.

Both concepts had merit, but as it played out, Breckinridge would advance with his 24 guns while Robertson stayed back. This divided command and control resulted in many of the batteries going into action piecemeal or not at all.

Second, the Union artillery was superbly controlled.

It was positioned to provide concentrated fire in defense of the ground on both sides of McFadden’s Ford. As the fighting progressed, Captain Mendenhall brought additional artillery into action. Interestingly, nine months later at Chickamauga, he would attempt a similar massing of artillery on September 20. There he arranged 29 guns from six batteries, five of which had been with him at McFadden’s Ford, on the high ground west of Dyer’s Field in an attempt to check Confederate penetration of the Union defenses. At Chickamauga, however, he had the support of only a few infantry regiments and was unsuccessful, as the Confederates were able to flank his artillery position.

Third, the Confederate attack went too far. The objective of Breckinridge’s attack was to capture the high ground east of McFadden’s Ford, which he did. Whoever controlled this ground would have two tactical advantages: It could be used to enfilade the other’s defensive line with artillery, and, in turn, it would deny the enemy the advantage of enfilading artillery fire. The attack was timed so that the ground would be captured just before sunset. That would give Rosecrans minimal time, if any, before it got dark. In addition, Breckinridge would have the entire night to organize and strengthen his brigade’s defensive alignment.

Had the Confederates stopped once they captured the high ground, they had options to hold their position. Although they were within range of Union artillery above McFadden’s Ford, depressions and folds in the open ground offered them ample protection. Also important was that they could remain out of range of effective Union rifle fire.

Rather than stop and consolidate their position, many regiments pursued the Federals retreating toward the river. At this point, the attack began to lose cohesion, command and control broke down, and units became commingled.

Two months after the battle, General Hardee wrote a distinct appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of the Army of Tennessee and the Army of the Cumberland as exemplified by the fighting on January 2: “It is worthy of remark that at Murfreesboro, whenever the fight was confined principally to musketry, and the enemy had no advantage in artillery, we were successful. It was only when they had massed heavy batteries that we were repulsed. In every form of contest in which mechanical instruments, requiring skill and heavy machinery to make them, can be used, the Federals are our superiors.”

Matt Spruill is a retired U.S. Army colonel, author of 10 Civil War books, who resides and writes from Colorado. The fighting he discusses in this article can be fully explored in Winter Lightning: A Guide to the Battle of Stones River and Decisions at Stones River: The Sixteen Critical Decisions That Define the Battle, published as part of the University of Tennessee Press’ newest series “Command Decisions in America’s Civil War.”