The Battle of the Little Bighorn is the best known and least known clash in American history. In a poem penned within weeks of Custer’s Last Stand, Frederick Whittaker, author of the hagiographic “A Complete Life of General George A. Custer” (1876), captured the prevailing mood of the times:

Backward again and again they were driven,

Shrinking to close with the lost little band,

Never a cap that had worn the bright Seven

Bow’d till its wearer was dead on the strand.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who wrote the epic poem “The Song of Hiawatha” two decades earlier, blamed the battle on the broken 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie but memorialized Custer’s death in heroic terms in “The Revenge of Rain-in-the-Face.” So did Walt Whitman, in “A Death-Sonnet for Custer” (retitled “Far From Dakota’s Cañons” in Leaves of Grass).

Newspaper reporters fostered that image in interviews with Lakota leaders, once they had buckled under and returned to their reservations. More often than not the subjugated Indians told the whites what they wanted to hear. After citing their own heroism, the warriors cited the courage of Custer and his men.

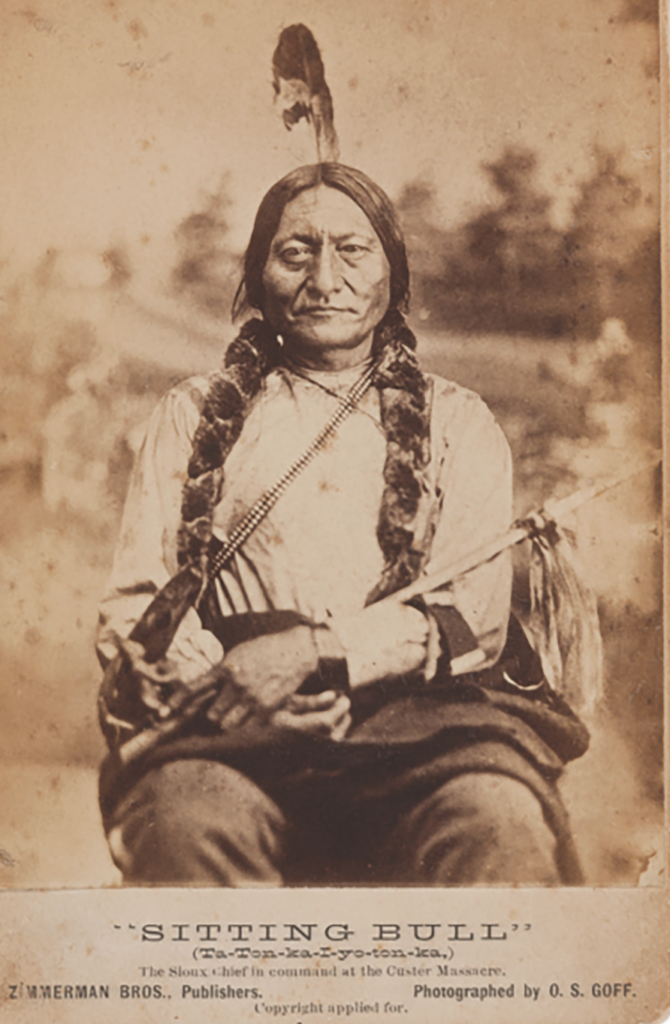

SITTING BULL SPEAKS OUT

“I tell no lies about dead men,” Sitting Bull reportedly told a New York Herald correspondent on Oct. 17, 1877, 16 months after the battle and from a safe distance in Canada. “These men who came with the Long Hair [Custer] were as good men as ever fought.…The Long Hair stood like a sheaf of corn with all the ears fallen around him.…He killed a man when he fell. He laughed.”

Gradually the Custer Myth — a term coined by U.S. Army Col. William A. Graham in his 1953 book of the same name — took shape. The soldiers had all fought bravely to the death, notwithstanding accounts (even those of military origin) of dead soldiers or abandoned cavalry horses found miles from the battlefield, which most news outlets ignored or discounted.

And they had sold their lives dearly. American Indian losses were said to be substantial, perhaps more than 100, counting mortally wounded warriors. No Indian accounts, however, not even those elicited through coercion or fear, substantiated far-fetched tallies of one dead Indian for every soldier.

The first detailed Plains Indian account, the narrative that may have launched the Custer Myth, was not filed by a newspaper reporter paid by the inch of copy. It was taken down at the Standing Rock Agency in Dakota Territory on Sept. 17, 1876, three months after the battle, by 1st U.S. Infantry Capt. Robert E. Johnston, a Civil War veteran and acting agent at Standing Rock. Johnston’s two interpreters and two independent witnesses signed the sworn statement.

ACCOUNT BY KILL EAGLE

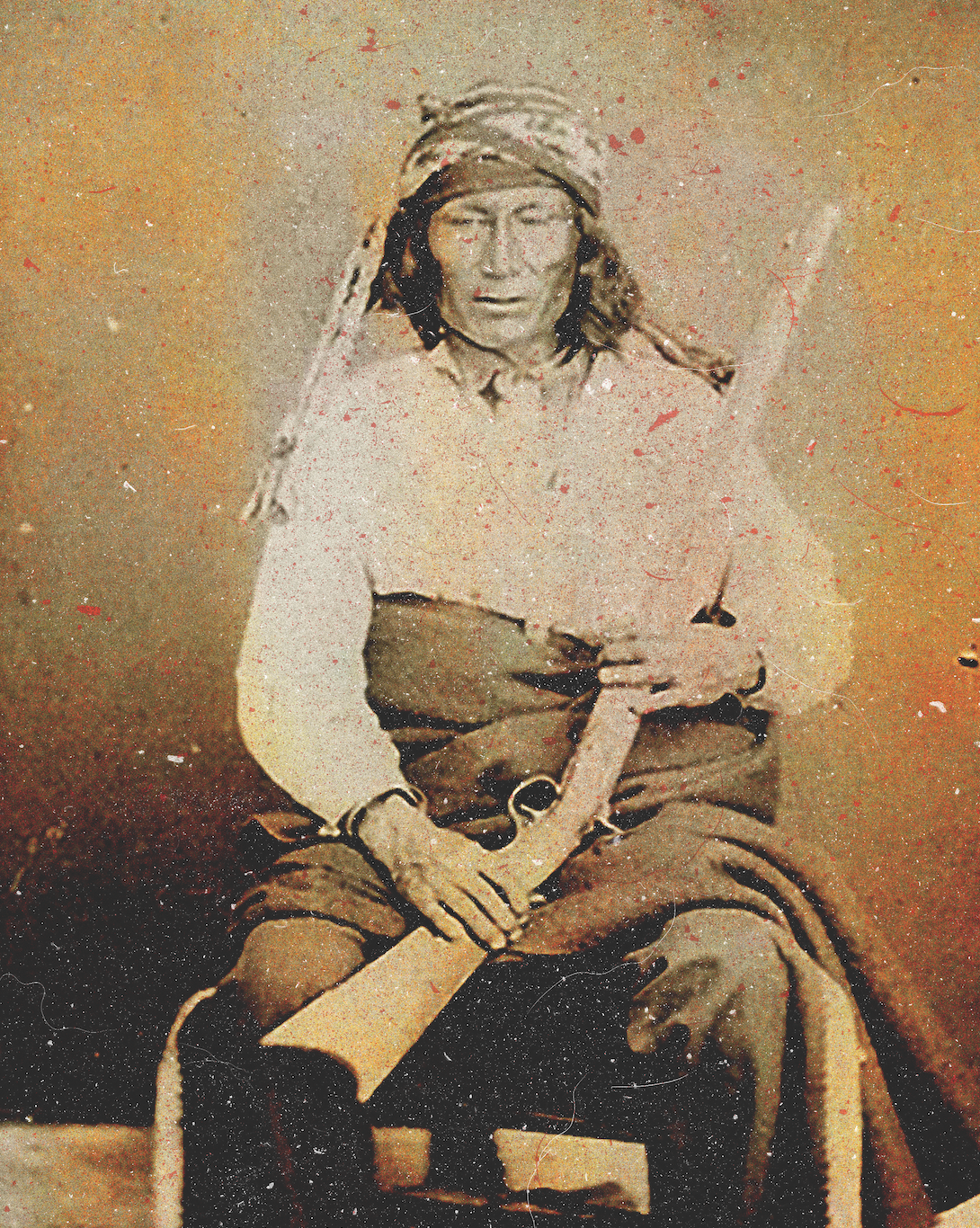

Its accuracy lay at the feet of not Capt. Johnston but Chief Kill Eagle of the Sihasapa Lakota, or Blackfeet Sioux.

“I have taken his statement with a great deal of care and am satisfied from his manner and bearing that he has endeavored to tell the truth,” Captain Johnston wrote in a preface to his interview with Kill Eagle. “He is 56 years of age, has been 13 years with the whites and is one of the most intellectual Indians I have met in Dakota.”

The captain was not a mythologizer. He was an Indian agent and professional soldier who sought to determine what actually happened.

“I have come to see you and have you make a statement for me to send to the Great Father,” Johnston prompted. “You will be careful and tell the exact truth?”

“How!” affirmed Kill Eagle. “You two interpreters were here, and there was an agent here, but no one told me to go out. I went in accordance with my own judgment. I had heard that there was an expedition going into the Indian country, but as I had heard the same every summer, I did not believe it. I was in want of lodges, robes and skins for making moccasins, and I went to get them. I thought I could get them and get away before any of the soldiers got there.”

“Before you left here last spring, you had a dance in the garrison,” Johnston said. “After the dance you fired your pistols in the air and told Colonel [John S.] Poland, ‘I am tired of this place. I am going away.’ Why did you do this?”

PROBING QUESTIONS

“I never did so,” Kill Eagle said. “The man who fired off the pistol did not belong to my band. He was a hostile. He fired off his pistol and said, ‘This is the way a brave man acts.’ I did not know he was going to fire. I asked him why he did it. He made no reply. The man was killed in the fight.”

“How many young men did you have with you who did not come back?” Johnston asked.

“One, Little Wound’s son,” Kill Eagle said. “He died out there.”

“These are all middle-aged men,” Johnston said, gesturing to the chief’s followers in the room.

“Where are your young men?”

“I do not go around all the lodges,” Kill Eagle said evasively. “My children are all girls.”

“Are there any young men here [at the agency] I have not seen?” the captain asked.

“We have no others, only what you have seen.”

“What were the names of the chiefs?” Johnston asked in reference to those at the Little Bighorn.

“I can’t say.” Kill Eagle’s dodge prompted Johnston to switch tactics and suggest names.

“Is Gall out there?”

“He is, with as big a belly as ever.”

“Is Rain-in-the-Face out there?”

“I don’t know. He was there, and I think he came to Cheyenne [River] Agency and went back to the hostiles again.”

“Is Plenty Crow out there?”

“Plenty Crow has never been away,” answered Kill Eagle, before again claiming ignorance. “I was not allowed to go around and see who was there or learn anything. I was watched all the time. I am in earnest when I say they guarded me closely day and night.”

“Did you all have guns when you started?”

“We had only what we turned in.”

“Did you have plenty of ammunition?”

“The sale of ammunition was stopped here before I went away. I was displeased with that, and I thought I would go out and starve anyway. I thought I could kill some game with arrows.”

“Did you have plenty of provisions when you started?”

“No, sir. The rations were very scarce; that was the reason I wanted to go out and kill some game.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

11-DAY JOURNEY

Kill Eagle then described a journey of 11 days to a place from which Indians collected whetstones. The morning after their arrival warriors rode back into camp to report the approach of white men.

“I answered, ‘Very good, I will go and see them,’” Kill Eagle recalled. “We went to see if there were white men, and instead of being white men, it was a herd of buffalo. We killed 45 of them, including two sick calves. This is what we lived on.

“I then called my men to a feast of buffalo meat and said, ‘This is what induced us to leave the agency. Now we have got it, we will turn by a roundabout way and return to the agency.’ My brother-in-law (who is dead) said, ‘No. Here is the village over at the place where they get blue earth [meaning Sitting Bull’s village]. We will go over there and get skins for moccasins, etc., which we need, and then return to the agency.’ And in doing this, he plotted my death but died himself.”

Staying put for the time being, Kill Eagle’s band slaughtered another 30 buffalo and returned to camp. The next morning unknown Lakota horsemen rode in.

“These were Indians coming from Sitting Bull’s village,” Kill Eagle said. “From them I heard from Sitting Bull’s camp. They told me there were contributions being made in Sitting Bull’s camp for me, and that I should make haste and get there, that they would make my heart glad.”

“When I got to the camp, I found the Indians starving, but they killed dogs and made a feast for me and told me, notwithstanding I was tired, I must march again the next day and camp where the buffalo were. In the morning the camp moved to Cottonwood Creek. I was the last to move, and when I got into camp, they were bringing in buffalo meat.

BUFFALO FEAST

Now that they had meat, the ‘Crow Society’ of the ‘Uncpapas’ [Hunkpapas] made a feast for me. I went to the feast, and a young man made me a present of a large roan horse and said to the Indians: ‘Here is a man that lives with the white men. You have invited him to come out here and get robes and skins.

Now he is here, why don’t you speak? This is why I have given him the horse. Now come forward and give him your robes and skins.’ They gave me 34 robes packed on horses (horse and all) and said, ‘Here is what you came for—take it and go.’ These gifts made my heart very glad. The young man who gave me the roan horse was named ‘Spotted Eagle.’

“The next morning I got on my horse and went to an Indian soldier’s lodge, where there were many soldiers assembled, and said to them, ‘My kindred, I came out here for robes and skins. I have got them. Now my heart is glad, and now, my friends, be merciful to me and let me go back to the white men.

“They all answered, ‘How!’ but one man jumped up and spoke differently. There were four chiefs of soldiers there, who sat in the back part of the lodge. They said, ‘You have not spoken well. We are killing buffalo. Wait until we have sufficient to send in with you, and when you get it, you will have plenty meat to speak with, and then your heart will be glad.’”

“From that day I was to suffer,” Kill Eagle said.

Resuming his narrative, Kill Eagle steadfastly asserted his unwillingness to join the larger Lakota party. “The next morning the camp moved, but I remained behind. I pretended not to notice their movements, but the Indian soldiers surrounded my camp and made me move with them, the Indian soldiers marching behind and on both sides of us, so that it was impossible for us to get away.”

SUN DANCE

When the party reached the Rosebud, the Indian soldiers invited Kill Eagle’s men to a Sun Dance, promising a horse to any who needed one. Kill Eagle said they were guarded every step between the Rosebud and the village on Greasy Grass Creek (aka Little Bighorn River).

“We camped very close to this creek, and all at once there was a great commotion, it being reported that white men were coming.

I got on my horse and said, ‘Pity me, my friends, we come from the whites, and they want you to listen to me. You are all grown men and must obey me. This nation here [the bands of Sitting Bull and others] fights with the whites, but the whites are our friends, and we don’t bear arms against them.’

“The Indians then went out to battle, but there came a herd of buffalo, and I and my men went after the buffalo and brought back buffalo meat. “When the Indians returned from the battle, they denounced me as a traitor, because I did not go on to the fight.”

Soon breaking camp, the Indian soldiers compelled Kill Eagle’s band to fall in with them. The chief’s refusal to do battle with Custer’s 7th U.S. Cavalry prompted those who had to taunt and otherwise provoke Kill Eagle and his men.

“They abused and whipped my men,” he said. “They can show the marks today.” Captain Johnston noted that a number of warriors present did in fact exhibit wounds made by knives,

lances and quirts. Kill Eagle himself bore a rather large wound on his hip. He said the hostile Indians also set fire to his band’s lodges and killed some of their horses. The outraged chief

returned the insult, killing one of their mounts. “After this they treated us still worse.”

Seeking to placate his abusers, Kill Eagle had his women prepare a feast of wild turnips and invited the Cheyennes in camp to the feast. Members of four warrior societies accepted the invitation and promised to intercede for Kill Eagle’s band. “You have been mistreated,” one Cheyenne chief told Kill Eagle, “but hereafter we will protect you. We are 500 lodges strong. Go your way, and we will stand between you and Sitting Bull’s men.”

DIFFICULT JOURNEY

The following night was especially dark and windy, so Kill Eagle had his people quietly strike their lodges and flee. Despite the promise of the Cheyennes, he said, Sitting Bull’s soldiers set out after them. The band wore out seven horses in their efforts to escape, but they got away. “When I came into camp,” Kill Eagle said, “I found turtle, fish and beaver, and this was our food.” He may have shared the last detail in a tone of disgust, as most Plains Indians detested eating fish.

Having recorded Kill Eagle’s narrative, Capt. Johnston pressed the Sihasapa Lakota chief for specifics about the battles on the Rosebud and Little Bighorn.

“How many warriors had Sitting Bull in this battle [Rosebud]?” the captain asked.

“A great many. I could not tell how many.”

“Did they have plenty of arms and ammunition?”

“They seemed to have. I could not tell, as I had not opportunity to get about to see them. All the Indian soldiers who were guarding me had splendid arms.”

“Did they have needle guns?” [Prussian army Dreyse breechloading rifles, which by 1876 were obsolete in Germany but popping up throughout the West as surplus.]

“They had all kinds of guns—Henry rifles, Winchesters, Sharps, Spencers, muzzleloaders—and many of them two or three revolvers apiece. All had knives and lances.”

“Did the [Indian] soldiers who were guarding you have plenty of ammunition?”

“Yes, their belts full, and the best kind of arms, fixed ammunition, metallic cartridges. All of us here had very bad guns. You see what we turned in.”

“In this fight [Rosebud] how many Indians were killed or wounded?”

THE WOUNDED AND THE DEAD

“Four killed and left on the field, who were mutilated by Crow Indians, and 12 died in the camp.”

“How many Indians were killed on the right of the camp [on the Little Bighorn] in the fight with [Major Marcus] Reno?”

“Fourteen were killed on the field with Reno, and 39 died on the field with Custer. I know of seven who died of wounds within camp afterward.”

Kill Eagle’s 16 dead Indians on Reno’s field and 39 on Custer’s may have included 10 women and children known to have been killed during the battle. In an 1886 interview Hunkpapa Chief Gall said 43 Indians had been killed, including two of his wives and three of his children. Eight years later Rain-in-the-Face claimed the Lakota had lost 14 to 16 warriors. Major Reno counted 18 dead Indians on the field. Kill Eagle’s numbers fall in the general range.

A WHITE MAN’S ARM

Kill Eagle insisted Sitting Bull’s soldiers tortured no one during or after the Rosebud and Little Bighorn fights, though mutilation of the dead, as practiced, appalled even many Indians.

“When we were in the council lodge, smoking [after the Rosebud fight],” Kill Eagle recalled, “a warrior named Black Moccasin, a Cheyenne, brought in a white man’s arm.

“He began beating me and my men over the head and shoulders with it, and said, ‘Here is your husband’s hand.’…They brought in Crow Indian scalps and beat us over the head with them. If ever one of these men comes into this agency, I vow to kill him.”

“Did Sitting Bull take any prisoners alive?” Johnston asked of Custer’s Last Stand on the Little Bighorn.

“He did not. He took no one alive. It was like a hurricane and swept everything before it.”

Kill Eagle said the fight with Reno began about noon and lasted only a few minutes, while the fight with Custer continued almost until sundown.

“The United States troops were all killed on the east side,” he repeated. “None crossed the stream.”

Johnston wrapped up the interview with questions about specific participants.

“How old do you think Sitting Bull is?”

“About 40 years.”

“What is the color of his hair? I heard it was light.”

“He has light hair.”

“Is he light himself?”

“He is not a white man,” Kill Eagle replied. “You can’t expect an Indian to be white.”

“How large a man is he?”

“About 5 feet 10 inches. He is very heavy and muscular and big around the breast. He has a very large head. His hair is not long; it only comes down to his shoulders.”

BROTHER TO BEAR’S RIB

“I have heard that there was a Spaniard fighting with the Indians. Did you see him?”

“There was once a white man in camp, but he went to Spotted Tail’s [agency] before the fight.”

Kill Eagle made his mark at the bottom of the statement, and Afraid of Eagles, a brother to Bear’s Rib, subchief of the Hunkpapa Lakotas, corroborated his testimony. “I have been with Kill Eagle,” he told Johnston, “and what he tells you is just what I would tell you.”

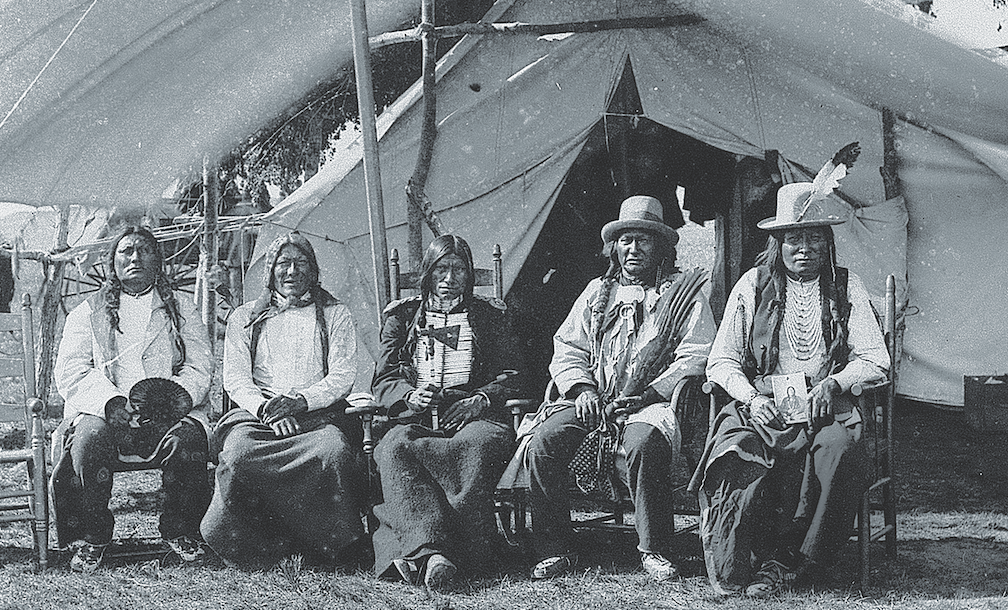

Kill Eagle’s account of events on the Rosebud and Little Bighorn contributed one particular insight to the Custer Myth—that Sitting Bull ruled his tribe as a de facto dictator and master strategist. The real Last Stand was not a Sioux ambush but a surprise attack by the 7th Cavalry that backfired once the Indians overcame their astonishment. Custer and Reno lost 268 soldiers and scouts. Kill Eagle’s Indian casualty list, while high, falls far short of the notion a warrior died for every soldier or scout.

Kill Eagle’s neutrality may also have been a myth. According to a Hunkpapa account from Standing Rock—written by Indians for Indians—Kill Eagle and about 20 of his warriors fought right alongside those desperate to save their families. His story of his reluctance in the face of Sitting Bull’s bullying tactics may have been prompted by similar motivation. Warriors can’t hunt buffalo to feed their wives and children while lingering in a guardhouse or moldering in the ground.

Wild West special contributor John Koster is the author of “Custer Survivor” (2010) and “Custer’s Lost Scout” (2017). Kill Eagle’s account appears in “The Custer Myth,” by Colonel William A. Graham, and the casualty statistics in Custer in ’76, by Walter Mason Camp.

This article originally appeared in the June 2017 print edition of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.