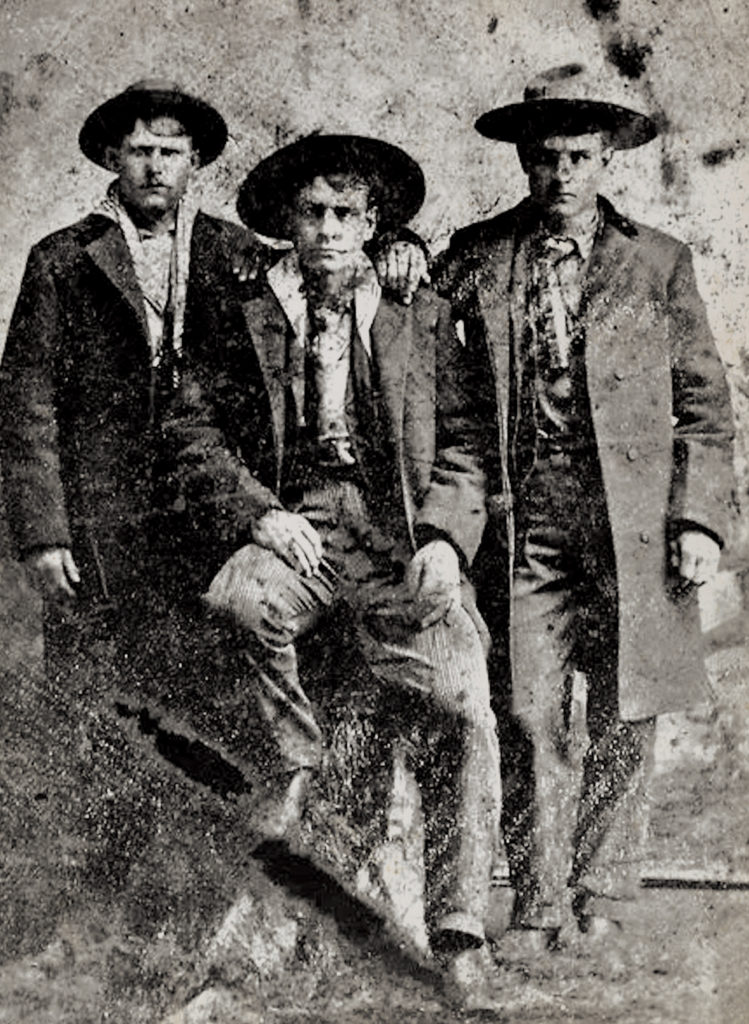

Wild Bunch gang leader Butch Cassidy (real name Robert LeRoy Parker) and cohort the Sundance Kid (Harry Alonzo Longabaugh) are known for having robbed trains and committed various other crimes without killing anyone. Not so Wild Bunch member Kid Curry, born Harvey A. Logan in Iowa in 1867. In my 2012 book He Rode With Butch and Sundance: The Story of Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan I note that Curry has generally been credited with eight or nine killings, some sources stating the figure as high as 40. But such figures are unreliable. “The only killing that can definitely be attributed to Curry, arguably in self-defense, was the result of his saloon brawl with miner ‘Pike’ Landusky in Montana,” I wrote back then. “Still there are modern writers who persist in placing him at the scene of nearly every suspected Wild Bunch killing, even when it can be shown that time, distance and other circumstances make this highly unlikely if not impossible.”

In retrospect, that doesn’t preclude the possibility Curry killed more than once. Two contemporary sources suggest a realistic toll, while the available evidence offers up the most likely candidates for consideration as Curry victims.

Alleged Victims

The first assertion comes from one of Curry’s avowed enemies—Robert A. Pinkerton, who operated out of the New York office of his father’s Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Pinkerton appeared to ignore the apocrypha about Curry when wiring the chief of police in Knoxville, Tenn., after the Kid’s capture east of town on Dec. 15, 1901: “Send you and all concerned hearty congratulations on important arrest made. Logan is one of the worst criminals in the West. He is a leader of train and bank robbers, and as such has no equal. He has committed three murders and is an expert jail breaker. Suggest that you put guard on him day and night.”

The second source of Curry’s possible kill count is the outlaw himself. The Kid spent much of the week before his capture drinking and shooting pool in the Knoxville bars. A local paper reported that he regularly flashed a roll of $20 bills and a couple of revolvers. When full of liquor he boasted to fellow patrons he was “something of a man himself” and claimed to have made three men “bite the dust.” One might assume Curry, when drunk and bragging, would have been inclined to claim a more impressive figure. But as he stated a more credible toll of three, a number that happens to agree with that quoted by Pinkerton, it stands to reason the Kid was telling the truth, or something very close to it.

In their 1954 Pictorial History of the Wild West authors James D. Horan and Paul Sann provide a Pinkertonlike chronological list of killings most commonly attributed to Curry. Rife with misspelled names and incorrect dates, it tallies nine such victims, though the authors credit no official agency or any other source for that matter. The list, with corrections in brackets, follows:

1. [Powell] “Pike” Landusky, Landusky, Mont.—Dec. 25 [27], 1894

2. Sheriff Hagen [Josiah Hazen], Conners [Converse] County, Wyo.—June 5, 1899

3 & 4. Norman brothers [actually two unrelated Mormon men, Andrew Augustus “Gus” Gibbons and Frank LeSueur, St. Johns, Ariz.]—June [March 27] 1900

5. Sheriff Scarborragh [former Deputy U.S. Marshal George Scarborough], Apache County, Ariz. [Deming, N.M.]—July 1901 [April 5, 1900]

6 & 7. Sheriff John [Jesse M.] Tyler, Moab [Grand] County, Utah, and deputy [posse member] Sam Jenkins—May 16 [26], 1900

8. Oliver Thornton, Painted [Paint] Rock, Texas—March 27, 1901

9. James [“Jim”] Winters, Montana— July 26 [25], 1901

A similar list compiled by Pinkerton agent Lowell Spence records seven murder victims, minus George Scarborough and Oliver Thornton. Spence submitted his list for the agency records along with a document titled “Logan’s Log,” in which the Pinkerton agent describes having diligently tracked Curry’s activities from June 2, 1899, to Dec. 15, 1901. Logan’s Log does not list five killings attributed to a gang of five that rampaged through Arizona Territory and Utah in spring 1900. It mentions only three victims: Thornton, Josiah Hazen and Jim Winters. Spence apparently wasn’t certain who killed Thornton; he notes only that George and Ed Kilpatrick were indicted for the crime, though “Logan [was] in it too.”

Does the omission of five killings in Logan’s Log mean Spence believed Curry had no hand in those murders? Furthermore, did the Pinkerton man intend to attribute the seven killings on his overall list to Curry alone or to the Wild Bunch in general? While the seven included Landusky, the latter’s name is absent from Logan’s Log. It’s possible Spence considered Curry’s first killing a matter of record not requiring further documentation. After all, the testimony of witnesses at a coroner’s inquest into the Landusky murder is irrefutable. To sum up, Pinkerton agent Spence’s nominees for the Kid’s kill count include at least Landusky, Hazen and Winters. Note, however, that none of the above referenced documents lists another killing often attributed to Curry—that of Deputy Sheriff William “Billy” Deane, of Johnson County, Wyo., in 1897.

Some writers assert that by early 1899 Curry had accompanied Cassidy and gang member William Elsworth “Elzy” Lay to southwestern New Mexico Territory and there, under the alias Tom Capehart, hired on at the WS Ranch near Alma. This bit of mythology may have been started by New Mexico cowhand, detective and ranger Charles A. Siringo. “‘Kid Curry’ knew every foot of this whole country, as he had been a cowboy along the line of New Mexico and Arizona under the name of Tom Capehart,” Siringo asserts in his 1919 autobiography, A Lone Star Cowboy. “Several years previous Capehart had shot and killed Geo. Scarborough.” Subsequent Wild Bunch/Curry biographers, including Horan, Charles Kelly and Brown Waller, repeated Siringo’s assertion, adding their own surmises.

As Capehart was among the prime suspects in the gang of five (which included Wild Bunch members Will Carver and Ben Kilpatrick) believed to have murdered Gus Gibbons, Frank LeSueur and Scarborough in Arizona Territory and Jesse Tyler and Sam Jenkins in Utah, Curry was thus tied to those killings under that presumed alias. The only problem with that erroneous assumption is that the real Tom Capehart, a Texas cowhand, was working at the WS Ranch at the time Curry was said to have hired on. It would have been ludicrous for the Kid to have assumed as an alias the name of someone with whom he was reportedly working.

In fact, no known sources place Curry in the Southwest at the time of the five known murders attributed to the gang of five. Allowing for Landusky as one of the Kid’s victims, that leaves four men to consider as possibly having met death from Curry’s guns—Deane, Hazen, Thornton and Winters.

Examining the Evidence

Deputy Sheriff Billy Deane was shot down on April 13, 1897, some two years and four months after the death of Landusky. Johnson County Sheriff Al Sproul had hired Deane specifically to arrest cattle thieves. Although he was considered a cool and determined man, Deane’s decision to ride out alone to capture or kill fugitive outlaws was pure foolishness. He set out south from Buffalo and on the morning of April 13 confronted two members of a gang of rustlers at the Griggs’ family-run post office. The gang, apparently intent on getting its mail, was thought to have included “Flatnose” George Currie and the two “Roberts boys” (aliases then used by Curry and the Sundance Kid). Deane pushed hard for a gunfight, but the rustlers rode off.

Deane went in pursuit, and a few hours later, near the Kaltenbach sheep ranch, he spotted four men he took to be the rustlers riding toward him. Drawing to within 400 or 500 yards of them, the deputy jumped from his horse and shot at the oncoming riders. Promptly dismounting, the four returned fire. Three of their bullets found their mark, and Deane bled out within minutes. Witnesses testified that as many as seven men shot at the deputy, two having ambushed him from a draw or cutbank.

Given the evidence, or lack thereof, Deane is not a good candidate to mark down as one of Curry’s victims. Even though the prime suspects were members of the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, they were never officially identified, and authorities made no arrests in the killing. The April 22 Buffalo Bulletin reported that the jury at a subsequent coroner’s inquest found “the deceased came to his death from a gunshot by parties unknown.” With four to seven men shooting at a range of 400 to 500 yards, it would be next to impossible to identify Curry, let alone single him out as the responsible gunman.

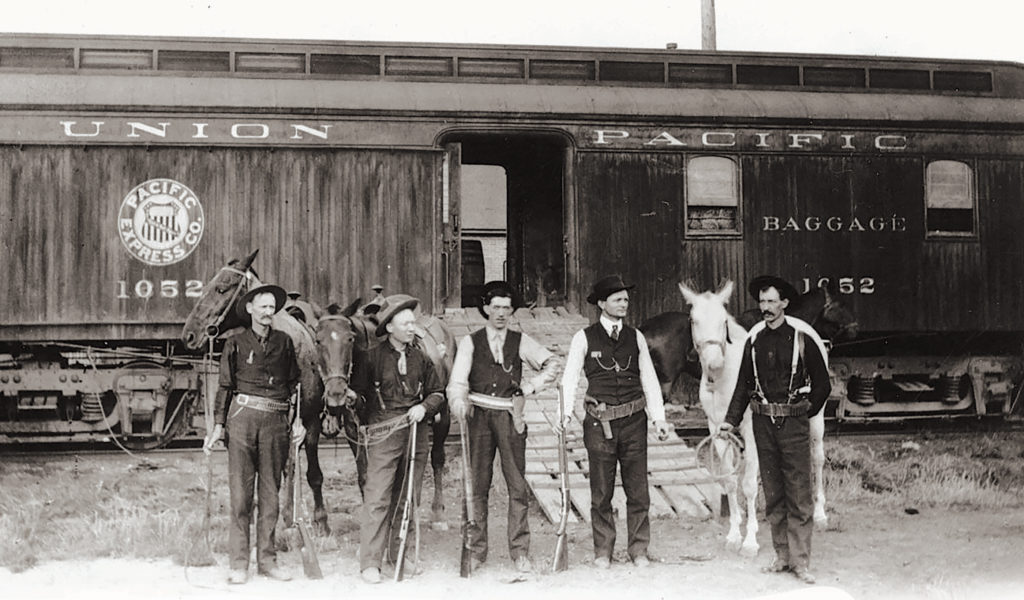

Little more than two years later, on June 5, 1899, Converse County, Wyo., Sheriff Josiah Hazen was ambushed while trailing three men suspected of the Union Pacific train robbery at Wilcox three days earlier. The posse tracked the fugitives—George Currie, Kid Curry and the Sundance Kid—to a spot along Castle Creek, roughly midway between Casper and the outlaw hangout also known as Hole-in-the-Wall. Sheriff Hazen and Dr. John F. Leeper of Casper (though some sources claim the second man was Union Pacific Special Agent Frank Wheeler) dismounted and walked up a draw, searching for the tracks of the outlaws’ horses. Hazen found the trail and called to Dr. Leeper. The latter had approached to within feet of the sheriff when the outlaws suddenly opened fire from concealment.

The newspapers called it a volley or succession of shots, one posseman recalling the reports of three distinct guns. “At the first shot Sheriff Hazen threw up his hands,” reported the June 8 Wyoming Derrick, “shot through the abdomen, the ball entering the right side and passing through.” The outlaws kept the posse pinned down for the next several minutes to cover their escape north along the creek. Hazen was taken first to Casper, then to his home in Douglas, where he died early the next morning.

The June 10 Cheyenne Daily Sun-Leader stated that some members of the posse had “returned a few shots…but the robbers could not be seen and, [as] they use smokeless powder, could not be separately located.” Although no one in the posse could be sure who’d shot Hazen, there’s a possibility the bandits themselves knew. First, the two parties had been in much closer proximity than those in the Deane confrontation. Second, this gunfight had pitted just three outlaws against two posse members. Finally, if we’re to believe the report that the first shot had been distinct from the volley or succession of three, the bandits may have known who among them fired the fatal bullet. Hazen certainly could have been one of the men Curry claimed to have made “bite the dust.”

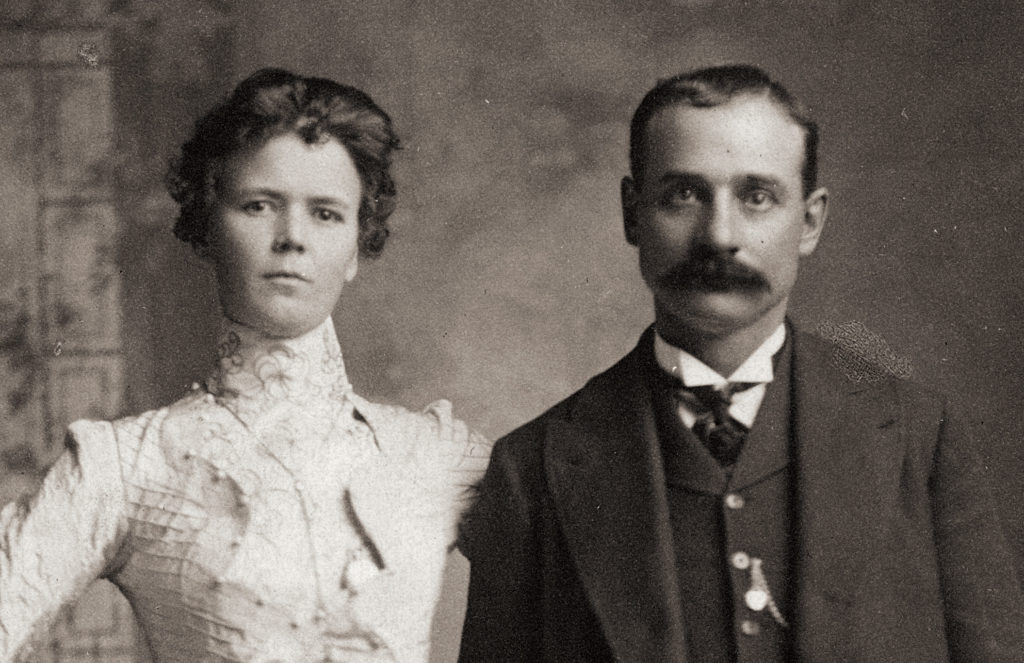

Trying to identify the person who murdered Oliver Thornton is, at this late date, an exercise in futility. Wild Bunch members Curry, Carver and Ben Kilpatrick were present at the latter’s Planche Spring family farm, between Eden and Paint Rock, in Concho County, Texas, in late March 1901. They were relaxing and laying low in the wake of a fall 1900 celebration with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in Fort Worth, during which they posed for the infamous “Fort Worth Five” photo. They had designated the cow town as a rendezvous point after having split forces to hold up both a Union Pacific train at Tipton, Wyo., and the First National Bank of Winnemucca, Nev.

On March 23, 1901, Butch, Sundance and the Kid’s companion, Ethel Place, arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on a steamship out of New York City. On or around the same date the other three gang members, who’d been posing as dealers in polo ponies and touring west Texas in a rubber-tired buggy, arrived at the Kilpatrick family farm.

On March 27, the day of the Thornton shooting, Ben’s younger brothers, George, Ed and Felix, and his sisters, Ola and Alice, were also present. An initial report of the killing appeared in the April 6 Devil’s River News, out of Sonora, Texas. “The reports which have been received in San Angelo are meager and conflicting,” the newspaper equivocated, before spilling details:

“Oliver Thornton, who was an employee of Ed Dozier and working on his farm, had been greatly troubled by hogs belonging to the Kilpatricks.…He went over to the Kilpatrick house to ask them to keep their hogs out. Ed Kilpatrick, George Kilpatrick and Walker were playing croquet. [Thornton, armed with a Winchester] threw down on the crowd and demanded that they keep the hogs out of Dozier’s premises. Ed Kilpatrick stated that the hogs were [his brother] Boone Kilpatrick’s, and that they wanted no trouble, and that Walker then shot him.”

“Walker” was Charles Walker, an alias of Will Carver. Curry, also present, was using the alias Bob McDonald. While the Pinkertons knew those aliases, local authorities were unfamiliar with them, a fact the Kilpatricks exploited to initially mislead those investigating the shooting.

George Kilpatrick later identified Walker as Carver and claimed McDonald had killed Thornton. However, the newspaper’s description of Walker as “a small man weighing from 135 to 140 pounds, dark complexion, heavy brown mustache, a bald head and aged between 35 and 40 years” more closely resembled Curry than Carver. Several months later Kilpatrick’s older brother Boone (who wasn’t present at the shooting) told St. Louis detectives Carver had done the killing, though Boone deemed it justifiable homicide, insisting Will had shot Thornton as the latter was thumbing a shell into his shotgun.

“In considering our outlaws, Will Carver and Harvey Logan,” author John Eaton writes, “we have trouble in finding a motive. In a robbery or in self-defense these men would kill for the profit and preservation of their lives, but never over an argument concerning someone else’s hogs.…A killing would tell the law where they are and have it close in on them, just as this one did.” That same assumption is true of Ben Kilpatrick. A news item from St. Louis published in the November 19 Billings (Mont.) Gazette reported that Kilpatrick, while in custody, claimed to have killed Thornton to save the life of his brother (Ed or George), whom Thornton had covered with a pistol.

Texas rancher John Loomis referred to his neighbors the Kilpatrick boys as “natural born criminals” and suggested a younger outlaw (meaning either Ed or George) had killed Thornton in a bid to impress veteran gang member Carver. In March 1902 the younger Kilpatrick brothers were duly arrested and tried for the Thornton murder, but both were acquitted.

Taken as a whole, the evidence suggests that no one, except Carver and the Kilpatricks, was aware of Curry’s presence in the region or even knew what he looked like. Thus, there really isn’t any concrete evidence Curry had anything to do with Thornton’s murder.

The final man under consideration as one of the Kid’s possible victims is Montana rancher Jim Winters. After the July 3, 1901, Great Northern train robbery near Wagner, Mont., Curry, Ben Kilpatrick and O.C. “Deaf Charley” Hanks hid out in the Missouri Breaks until those hunting for them wearied of the pursuit. Around 6 a.m. on July 25, eight days after the posses disbanded, Winters had stepped out the back porch of his ranch house to brush his teeth when struck in the abdomen by two bullets. One slug lodged in his stomach, the other shattered his spinal column.

Among those alerted by the shots were six young Easterners staying at the ranch that summer to help with the haying. Sources differ as to whether Abe Gill, Winters’ stepbrother and partner, was also present that morning. A subsequent inquest lists the six Easterners as witnesses, one of whom reported having seen someone he didn’t recognize run up a coulee some 150 yards away in a crouched position. Warning shots from that shooter, or shooters, kept the six hands pinned down until about 8:30 a.m., when two were finally able to ride north to Harlem for a doctor.

Authorities found empty .30-40 Winchester shell casings beside an old hog pen west of the ranch house, behind which the killer (or killers) had taken up a firing position. From there two sets of footprints led to a campsite in a creekside willow thicket. On the ground were the butts of several hand-rolled cigarettes, while the shod prints of two or three horses led away from the creek. The evidence suggested two or three men had waited several hours for Winters to show himself. Authorities speculated the shooter had ridden away first, while his accomplice, or accomplices, provided covering fire. A three-man posse followed but soon lost the trail of the bushwhackers.

The next day, the 26th, the Fort Benton River Press named the Curry gang as prime suspects. “The Curry gang and their sympathizers have had it in for Winters ever since the latter killed John Curry about five years ago, an occurrence which was justified by Curry commencing to fire at him with a six-shooter,” the newspaper wrote. “[John] Curry claimed the Tressler Ranch, which Winters had bought, and tried to enforce his claim by ordering its owner out of the country.”

Winters had recently told Siringo he expected to be waylaid and killed by John’s brother, Kid Curry. But five years had passed since the Winters/John Curry gunfight, and all that time Kid Curry hadn’t shown any inclination to seek revenge. Anyway, Winters had plenty of other enemies. Residents of north-central Montana’s Little Rockies, for example, were not happy Gill and Winters had invited the various barroom posses to camp on their ranch. While they supposedly scoured the country for the Great Northern bandits, posse members had cut barbed wire fences, ridden through neighbors’ grain fields and intermittently ducked into Landusky to fill up on whiskey and shoot up the town. One upset neighbor reportedly threatened that unless Winters reimbursed him for damaged crops, he’d “get what Johnny Curry got.”

The verdict of the inquest was Winters had been killed “by some person or persons unknown to this jury.” On September 3, after a thorough investigation, a Fort Benton grand jury was only able to conclude Winters had been murdered “by a fugitive from justice…one of the parties to said [Great Northern] train robbery.” While the grand jury lacked the evidence to charge Curry with murder, Winters may well have been the final victim on the Kid’s list of three men he made “bite the dust.”

In determining the identities of the alleged three (not nine) victims of Curry’s guns, with Pike Landusky as a given, the other two were most likely Josiah Hazen and Jim Winters. But without any confirmation from Robert Pinkerton or Curry himself, their identities will have to remain as speculation.

On June 7, 1904, Curry and two cohorts robbed a Denver & Rio Grande train outside Parachute, Colo. Two days later, on being cornered and wounded by a posse, the Kid fatally shot himself in the head. Questions inevitably arose over whether the dead man was in fact Curry, but Knoxville authorities who had interacted with the outlaw during his 1901–02 stay in their county jail identified the body from photos as that of Harvey Logan, alias Kid Curry. Confirmation of the deceased’s identity came in the form of a 3-inch scar atop his head—the relic of a wound inflicted on Curry by a nightstick-wielding Knoxville policeman.

Seattle author Mark T. Smokov has long had an interest in Kid Curry and other Western outlaws. Smokov’s book He Rode With Butch and Sundance: The Story of Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan is recommended for further reading along with Harvey Logan: Wildest of the Wild Bunch, by Donna B. Ernst, and Will Carver, Outlaw, by John Eaton.