DURING WORLD WAR II, direct contact between Nazi and Allied leaders was vanishingly rare. Two particularly dramatic exceptions occurred just before turning points in the war, both aimed at brokering a peace agreement. Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess made the best-known such contact, a year and a half into the fighting. The second, coming near the war’s end and far less remembered, was the work of an SS general named Karl Wolff, who invoked Hess, and left a host of troubling—and still-unsettled—questions in his wake.

In May 1941, as Germany was preparing to invade Russia, Hess secretly strapped himself into a Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighter-bomber, flew fast and low under the radar from Germany to Scotland, and parachuted very near his target, the estate of the Duke of Hamilton. His plan was for the duke—whom Hess claimed to have met at the 1936 Olympics—to put him in touch with the king, who in turn would arrange peace between Britain and Germany, allowing Hitler to focus on the East.

No one appreciated Hess’s sincere but delusional gesture. The duke claimed he did not remember meeting Hess. Even if they did meet, hardly anyone in England, the duke and king included, was willing to make peace with Hitler—who himself was unwilling to let anyone else make foreign policy. When told about Hess’s venture, Hitler let out a cry of surprise and rage, and came close to living up to his reputation as a “Teppich-fresser”—a madman who gnawed on carpets. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was initially nonplussed—Was this really the Deputy Führer? Was he acting on his own?—ordered Hess locked up. Somewhat sympathetic to Hess for trying to make peace, the prime minister directed that he spend the rest of the war in isolation but relative comfort; Hess went from the Tower of London to a fortified mansion in the countryside and then to a hospital in Wales, where he spent three years.

Wolff’s turn at peacemaking came in the last weeks of the war. Since late 1943 he had been the senior SS commander in Italy—essentially the Reich’s chief enforcer in that theater. His title was fearsome: SS-Obergruppenführer and General of the Waffen SS, Highest SS and Police Leader and Military Plenipotentiary of the German Armed Forces. He did not have as much military power as his Wehrmacht counterpart, who commanded more than three quarters of a million soldiers, sailors, and airmen—but he embodied Nazi political power.

Wolff had a variety of forces under his command. To fight partisans behind the front lines, he relied on some 160,000 troops, including foreign “volunteers.” This irregular war was not as brutal as that on the Eastern Front, but was marked by occasional excesses. Wolff also commanded some 65,000 Germans who were part of the police apparatus that searched out and arrested the Reich’s enemies, along with running prisons and a handful of labor and concentration camps.

By February 1945, the Allies had driven the Wehrmacht about four-fifths of the way up the Italian boot. The Germans were holding—just barely—south of Bologna in northern Italy. Elsewhere the picture was far worse for the Germans. Their last great offensive, the Battle of the Bulge, had failed, grinding to a halt well short of its objectives and seriously depleting Hitler’s few remaining reserves. Allied forces were now advancing relentlessly from the west, on their way to breach the Rhine in early March. In the east, the Russians had two huge daggers pointed at the heart of the Reich—one from across the River Oder, only about 50 miles from Berlin.

Wolff had some experience as a very junior army officer during World War I but was not a professional soldier. Still, he grasped that it was just a matter of time before the Allies would win. Further resistance would serve no purpose, resulting in needless loss of life and property. In his words, he was ready as early as mid-1944 “to do whatever was in [his] power” to end the war “should an honorable opportunity present itself.” When he saw that opportunity, he decided to act: late in February 1945 Wolff approved a proposal by two officers under his command, Colonel Eugen Dollmann and Captain Guido Zimmer, both of whom wore the black uniform of the SS but had a soft spot for Italy and its culture. Directed at Swiss military intelligence through intermediaries, they asked the Swiss—who, being neutral, could talk to both sides—to extend peace feelers to the Western Allies on their behalf.

The Swiss knew who to turn to: Allen W. Dulles, head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) base in the Swiss capital, Bern. The 52-year-old one-time diplomat was a Wall Street lawyer on extended leave from one of the great white-shoe law firms, Sullivan & Cromwell, where his older brother, John Foster, was a senior partner. Dulles was finding intelligence work far more interesting than the lucrative but dreary practice of corporate law; he actually enjoyed the thrill of operating on Hitler’s doorstep surrounded by enemy territory for much of the war. Besides, he was good at his job, cultivating productive relationships with everyone from Swiss bureaucrats to German walk-ins—one of whom, a midlevel official named Fritz Kolbe, carried briefcases bulging with secret documents and became one of the Allies’ most valuable German spies.

Dulles reacted to Wolff’s initiative by sending intermediaries to meet Zimmer and Dollmann on Swiss soil, where the two sides probed each other’s positions. To prove Wolff was serious, Dulles demanded that he release a senior member of the Italian resistance named Ferruccio Parri, one of Wolff’s most prominent prisoners and a high-value bargaining chip. Dulles was surprised by the quick, unconditional turnaround: by March 8, Parri and one other former prisoner appeared at the Swiss border—followed by Wolff himself. He wanted to see Dulles.

THROUGH A SWISS INTERMEDIARY Wolff forwarded what amounted to his peacemaking credentials. On top was his calling card—much like a business card today, bearing his official title. Attached was a long list of names of references, including Hess and Pope Pius XII, marked with short notes. Wolff included Hess presumably because the Allies could ask him about Wolff; the two men had known each other in Berlin when Wolff had been a member of Hitler’s inner circle. And Wolff, although not Catholic, had had an audience with the pope in May 1944 to discuss the prospects for peace. Wolff noted that at the pope’s request, he had released an Italian prisoner, and that the pope “stands by to intercede, if desired, at any time.” Complementing the references were letters recording instances of Wolff’s clemency and his role in protecting priceless art. He claimed hundreds of irreplaceable Italian paintings from the world-famous Uffizi Gallery in Florence had been moved to safety on his orders.

The Americans were not entirely sure what to make of Wolff. OSS files in Washington contained little more than a paragraph or two of information about him: born in 1900 near Frankfurt, service in a paramilitary corps after World War I, member of Reichsführer SS Himmler’s personal staff, regular visitor to Hitler’s headquarters. (Those last details were a major understatement: Wolff was at Himmler’s side from 1933 to 1943, rising to head his personal staff as well as to serve as his liaison to the Führer.) One file gave Wolff’s address in Berlin as Prinz Albrechstrasse 8, which was actually the headquarters of the SS, a combination of office space for executives and cellblock for prisoners being interrogated and tortured. There was mention of his moderately successful work in advertising between the wars.

Dulles’s assistant, the well-connected German American Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz, had heard of Wolff. The two even had some mutual acquaintances, and Gaevernitz knew that Wolff had interceded on behalf of a Catholic philosopher the Gestapo had threatened in 1939.

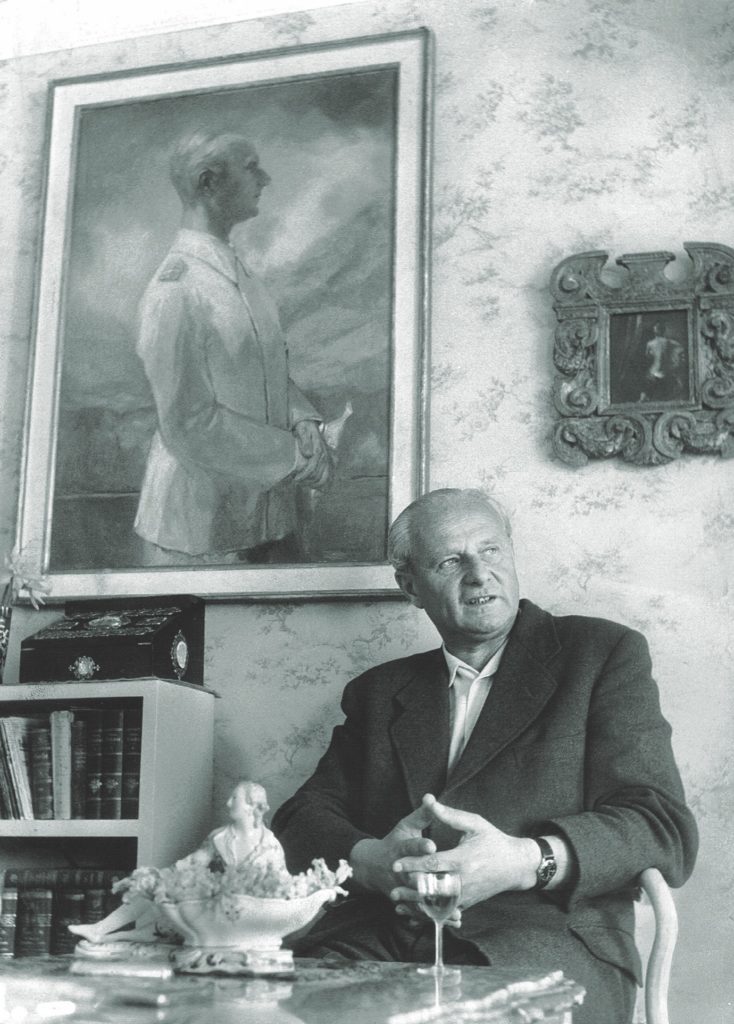

Dulles decided to see for himself what Wolff was like, and arranged to meet him shortly after he presented himself that March 8, at an apartment Dulles kept in Zurich for what he called “meetings of the touchiest nature.” It was located at the end of a quiet street and looked out on Lake Zurich. Dulles set the stage for the late-night meeting by starting a fire in the fireplace, his theory being that crackling flames helped visitors relax. Since American officials were uncomfortable shaking hands with Nazis, Dulles just nodded in greeting when Wolff arrived but offered his guest, who seemed ill at ease, a glass of scotch. He noted that Wolff was “a handsome man and well aware of it”: Nordic, well-built, with graying dark blond hair, pleasing features, and—especially for a Nazi—good manners. He had blue eyes and spoke High German without a regional accent, unlike Hitler, who never shed the Bavarian twang he’d picked up as a child and did not worry overmuch about his manners.

Wolff relaxed enough to tell Dulles what he could and could not do. Germany had lost the war, and the only sensible course of action was to surrender. He wanted the best for his country, and was prepared to act on his own to surrender the forces under his command. But the result would be far better if he, Wolff, could persuade the Wehrmacht commander in Italy, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, to surrender the hundreds of thousands of troops under his command as well. Wolff had a good relationship with Kesselring and, so long as no one betrayed his plans to Hitler, he just might succeed. Wolff did not ask for any kind of special treatment for himself.

Dulles reported his favorable impressions to Washington, especially that Wolff represented a “more moderate element in [the] Waffen SS, with a mixture of Romanticism”—an apparent reference to the Teutonic never-never land that Wolff believed in. This was where the men were cultured Aryans like himself, the women fertile like his two wives, the children with folkish names like his sons Widukind and Thorisman. The 44-year-old general was, Dulles summed up, “probably the most dynamic personality in North Italy and most powerful after Kesselring.” Dulles was eager to proceed, as was OSS Director William J. Donovan. Others in Washington were guardedly optimistic—so long as Wolff understood that the only possible terms were unconditional surrender.

THE BASIC IDEA—a local surrender in northern Italy—was straightforward. But the devil was in the details, and there was one complication after another. Wolff had repeatedly discussed the matter with the multi-talented Kesselring, a Luftwaffe general equally at home commanding air forces and ground troops. But just when Kesselring seemed on the point of yielding to Wolff’s arguments, Hitler transferred Kesselring to another command. Wolff had to instead work on his successor, General Heinrich von Vietinghoff—a more traditional army officer who was uncomfortable with the idea.

The regional friendly military command, Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ), wanted to form its own impressions of Wolff, and dispatched two of its most senior officers: the British Major General Terence Airey, responsible for intelligence, and the American Major General Lyman Lemnitzer, the assistant chief of staff at AFHQ. They met with Wolff in Switzerland on March 19.

Somehow Hitler and Himmler got wind of Wolff’s activities, without learning their full extent, and summoned him to Berlin for not one but two rounds of consultations. Wolff survived the hair-raising trips thanks to his good relationship with Hitler and his quick wits. He did take one precaution, which offers a clue as to what he expected, although not explicitly requested, from Dulles. Preparing a note to be delivered to the American in case Hitler or Himmler ordered his arrest, or if he died for any other reason, he asked that “Mr. Dulles… rehabilitate my name, publicizing my true, humane intentions; to make known that I acted not out of egotism…, but solely out of the conviction and hope of saving, as far as possible, the German people.” He also asked, “if this is possible,” that Dulles protect his two families, meaning his first and second wives and their children.

CHURCHILL AND American president Franklin D. Roosevelt were both briefed about Operation Sunrise, as Dulles had labeled the surrender negotiations. Churchill paid more attention to the matter than Roosevelt, who was seriously ill by that time. When Churchill insisted that the Soviets be informed, Stalin exploded in paranoid rage, accusing the British and Americans of maneuvering behind his back. (Nonsense, of course, since they had just told him what they were up to.) Roosevelt’s death on April 12 was yet another major complication, one that led Wolff to handwrite a letter of condolence to Dulles—the only one from an SS general officer to a senior American official. The prose was stiff, but the message was thoughtful: “…the passing of the President with whom you were so close must have been painful to you in equal measure as a man and a member of the government.” (Dulles was not actually close to Roosevelt but he was known in Switzerland as his personal representative.)

By April 20—coincidentally Hitler’s birthday—there had been so many complications that the British and American chiefs of staff ordered Dulles to break the link to Wolff and let their armies get on with the war. They were tired of waiting for the Germans in Italy to agree among themselves, and they did not want any more arguments with Stalin. They also knew that their military position in Italy was growing stronger by the day.

Despite the obstacles, Wolff stayed the course, continuing to work on Vietinghoff. When Vietinghoff finally—and reluctantly— agreed to go along with the surrender, Wolff renewed his offer to the Allies. A few days later Italian partisans surrounded Wolff and a few of his men at a villa in northern Italy. The partisans appeared intent on capturing or killing him, which would have ended Operation Sunrise. A tense standoff ensued. Dulles sanctioned a multinational rescue team—two carloads of Swiss officials, OSS men, and even two SS border guards—who drove through the surrounding cordon and freed the SS general. When Wolff happened to encounter Dulles’s man Gaevernitz at a border crossing, Wolff fervently thanked him and insisted on shaking hands. One report has Wolff proceeding to hug Gaevernitz—which, if true, would have been another one-off event.

Since the Germans had agreed among themselves to proceed with the regional surrender, Washington and London, at Dulles’s and AFHQ’s urging, withdrew their opposition to accepting Wolff’s offer. Two plenipotentiaries—one for Wolff and the SS, one for Vietinghoff and the Wehrmacht—made their way to AFHQ at Caserta, Italy, to sign an instrument of surrender on April 29. It was the day before Hitler’s death by suicide at his bunker in Berlin, which Soviet troops were about to overrun.

The instrument provided for the ceasefire to occur on May 2, which turned out to be several days before the general surrender on May 8. This meant that the capitulation in Italy was not as momentous as it might have been a month or two earlier, but it did prevent six days of bloodshed, and exposed Germany’s southern flank, hastening the final collapse. It also enabled the Western Allies to occupy the city of Trieste, preempting the communist forces of Yugoslavia’s Marshal Tito, then advancing from the southeast, from expanding their sphere of control. Not least, the surrender saved the great paintings from the Uffizi and other artwork—secreted in the mountains of Italy on Wolff’s orders—from being destroyed or shipped to Germany.

During and after the surrender, Wolff remained at his headquarters in a splendid Renaissance palace in the northern Italian town of Bolzano. The Wehrmacht set up nearby in a less grand but more secure complex of caves built into a mountainside. Like Vietinghoff, Wolff remained in command of his forces while the surrender was being implemented—a not uncommon phenomenon since transfers of power on such a vast scale could not happen overnight. During this period, which lasted some 10 days, the atmosphere for Wolff was like that of a well-deserved vacation after the extreme stress of the past months. The fighting had stopped, Hitler and Himmler could no longer threaten anyone, and Wolff was able to send for his family. The springtime weather in the mountains was glorious, and the ample stocks of food and wine made for good living. Gaevernitz even dropped by on May 9, and appears in a photo that seems to depict a relaxed, happy gathering of friends.

A sea change came on May 13—Wolff’s 45th birthday. The SS officers donned their dress uniforms—Wolff favored an elegant off-white tunic that looked far less threatening than the standard black SS outfit—and opened many bottles of champagne for them- selves and Vietinghoff’s staff. Then, unexpectedly, U.S. Army trucks rumbled up to the palace. MPs in white helmets arrested Wolff and his entourage—part of a routine roundup of Germans in uniform. They even took Wolff’s wife and their children to a rudimentary camp, which distressed Wolff greatly. He would come to see it as the first of many times when the Americans let him down.

WOLFF NOW BEGAN a unique period of confinement. Following Himmler’s death by suicide on May 23, Wolff became one of the senior-most surviving members of the SS. But he had also arranged the surrender in Italy, and was on friendly terms with Americans like Gaevernitz and, to a more limited extent, Dulles. No one was sure what to do with him. Should he stand trial as a war criminal—or serve as a witness? Wolff was willing to do either. He made himself available for endless interrogations, and later claimed that he wanted “to vindicate the decent part of the SS”—meaning that he wanted to counter the argument that the SS was a criminal organization, an increasingly untenable proposition as the damning evidence mounted.

The Americans decided that he was mentally unstable and opted for a third alternative, locking him up in two mental hospitals in Germany for a few months in 1946. Word came that Wolff believed that Jewish demons were after him; in the absence of any medical files, however, all claims of mental instability are hard to substantiate. Wolff later explained that the Americans interpreted his offer to defend the SS as “suicidal mania” and implied that they just wanted him out of circulation for a few months.

When he emerged from confinement, supposedly sound in mind and body, Wolff still did not fit into any category and began to be treated more like a prisoner of war. The Americans shifted him to British custody and, in 1949, he went through “denazification” in the British zone of occupation. Intended to purge Germany of Nazi influence, denazification was a quasi-judicial process instituted by the Allies but mostly run by German laymen who gathered evidence and presided over hearings.

The charges against Wolff related more to his status as a senior SS officer than to any specific war crimes or the crimes against humanity associated with the SS; there was still little evidence against him.

There was a good deal of mitigating testimony, however. Generals Lemnitzer and Airey submitted affidavits describing Wolff’s role in Operation Sunrise, as did Allen Dulles. Dulles’s one-page affidavit affirmed the facts, concluding in lawyerly fashion that “General Wolff’s action…materially contributed to bringing about the end of the war in Italy….” Gaevernitz appeared in person and enthusiastically defended him. The presiding judge was favorably impressed, crediting Wolff with time served and declaring that he would walk out of the courtroom with his honor “clean and unstained”—which he did, beaming, almost as elegant in a tan civilian suit as he had been in a Nazi uniform.

Wolff spent the next 13 years as a free man in West Germany, returning to advertising and becoming a prosperous executive. In 1961, the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the SS officer who organized much of the Holocaust, generated renewed interest in Nazi war crimes and led German authorities to take another look at Wolff’s case. Individual documents had by now risen to the surface of the sea of captured Nazi records showing that he had known of specific crimes and had urged German rail officials to make railcars available for the transportation of some 300,000 Polish Jews to Belzec and Treblinka, two of the main death camps.

Tried by a German court in 1964 for his role in the Holocaust, the aging Obergruppenführer had no end of explanations and excuses, chief among them that he was unaware of the Holocaust itself until March 1945. Given his position at Himmler’s side, this claim strained—and still strains—credulity, despite Wolff’s insistence that it was possible to be a decent SS officer. Erich von dem Bach- Zelewski, Wolff’s former SS comrade and friend who oversaw mass killings in the East during the war, testified that it was highly unlikely that Wolff did not know of the murderous “final solution”—especially after Wolff visited him in 1942 at an SS hospital where von dem Bach was recovering from a nervous breakdown that his SS physician attributed to his role in “the shootings of Jews, as well as [his] other difficult experiences in the east.”

This time Wolff did not charm the judge, who sentenced him to 15 years in prison. Even though he did not acknowledge his guilt, he was a model prisoner and enjoyed privileges that the Third Reich seldom granted to its detainees: furloughs to visit family and indefinite sick leave after he suffered a heart attack in 1971.

WHERE, THEN, SHOULD HISTORY place Wolff? Was he like the delusional Rudolf Hess? Kept secluded during the war in England, but prosecuted at Nuremberg postwar as a member of the Nazi elite, Hess claimed amnesia and sulked in the dock. Found guilty of crimes against peace and conspiracy—two of the more general charges levied—he spent the rest of his life in Berlin’s Spandau Prison. Or was Wolff more like the calculating Himmler, who committed a range of war crimes and crimes against humanity? Or, finally, was Wolff mostly a conservative German patriot who attached himself to a charismatic leader who deceived his followers and led the country into a ruinous war?

Wolff remains hard to categorize. But we can narrow the range considerably. Wolff’s own narrative—that of the conservative patriot—is easy to reject. The Nazi program was, from start to finish, not a conservative but a radical phenomenon, with its over-the-top racism and expansionist drive. Wolff never claimed to have been unaware of the Nazis’ anti-Semitism. He may not have proposed or planned the Holocaust. But, given his position in the SS—the most zealous instrument of Hitler’s policies—he was at least complicit. Moreover, he did not complain about Hitler’s wars of aggression—especially against Bolshevism— as much as about the fact that Hitler lost them. On the other hand, it was to his credit that he acted on his own to preserve life and property when he realized that the war was lost.

All told, then, Wolff is most like Hess. While the fit is not perfect, they were both Nazi true believers who wanted to make peace with the west, especially Britain and the United States. The difference was that Wolff was better at it, and—like a good advertising executive—far better at promoting his image.

A twist in the story came after Wolff’s daughter Helga converted to Islam in 1961 and changed her name to Fatima. She explained that she was looking for a way to come to terms with her family’s fraught history, and went on to become one of Germany’s leading Islamic public figures. In print, in person, and on the air, she shared her new worldview with the good manners that she had learned from her father. In 1984, Wolff reportedly followed her lead and professed the Muslim faith. When he died a few weeks later at age 84, Fatima recited graveside Muslim prayers. But unanswered questions remain: Did he finally understand and acknowledge his role in the Third Reich? Was he, like Fatima, trying to move beyond his past? The piece of rough-hewn rock over his grave is neither Christian nor Muslim, and tells us little. The simple plaque with his name and birth and death dates gives his title as “General, Retired,” as if Wolff wanted to be remembered as an officer who served his country instead of the Nazi killing machine he actually served. ✯