Inspired by Alexander the Great, the Roman emperor Julian set out to conquer Persia with a massive army, a bold plan, and a thirst for glory

From the Summer 2010 issue of MHQ

This post contains only a snippet of this article. Please purchase the Summer 2010 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History to read the entire article.

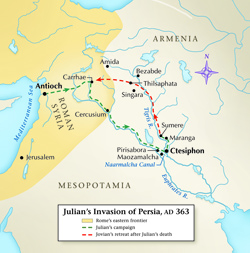

One day in early April, ad 363, the emperor Julian stood on an earthen mound and looked out upon a magnificent array of military might. Assembled before him were the legions of the Roman eastern field army, 65,000 strong, along with 1,000 transport vessels and 50 warships, a flotilla reminiscent of the one amassed by Xerxes to invade Greece more than 800 years before. Julian’s army had left its winter headquarters in Antioch a month earlier and paused here, at Cercusium, on the east bank of the Euphrates River. Three hundred miles to the south, on the Tigris River near modern-day Baghdad, lay Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sassanid Persian Empire. Julian planned a lightning assault on the city, part of a bold, if risky, scheme to crush the army of the Persian king Shapur II, one of the most celebrated and ruthless rulers of his generation. Victory, Julian promised his soldiers, would expand the empire, secure its eastern frontier, and fill Roman coffers—and the soldiers’ pockets—with Persian wealth. A successful campaign would also bring great glory to Julian. Elevated to the throne by his troops only a few years earlier at age 29, Flavius Claudius Julianus was one of Rome’s most educated and intellectual rulers. A keen student of history, he burned with ambition. Addressing his troops, he spoke of previous Roman rulers—Trajan, Septimius Severus, and Lucius Verus among them—who had tasted victory over Rome’s eastern enemies. He also must have thought of his personal hero, Alexander the Great, who had conquered Persia 600 years earlier; Julian fancied himself the Greek king’s spiritual heir. If his plan worked and brought a great empire to its knees, Julian too would be hailed as a world conqueror. N When Julian became sole emperor of Rome after the death of his cousin Constantius II in 361, he inherited a hotly contested eastern frontier. Roman influence on that frontier extended north into the kingdom of Armenia and south to Syria, northern Arabia, and the northwestern floodplains of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Yet for more than four centuries Rome had been forced to battle for these lands against its eastern rivals, principally the Parthians and the Sassanid Persians.

In the years before Julian came to power, the Sassanid dynasty produced a line of energetic and brilliant kings who forged a civilization with a cultural sophistication, wealth, and military might that matched or exceeded Rome’s. Their empire encompassed the central Tigris and Euphrates valleys leading to the Persian Gulf and the Iranian Plateau and areas east, including portions of central Asia (modern-day Uzbekistan and Pakistan) up to the edges of northern India.

Like their Roman counterparts, Persian kings were expected to secure and expand their empire. In King Shapur II, the Romans faced one of the greatest Sassanid rulers, a leader worthy of the title “Shahanshah,” or King of Kings. A fearsome warrior, Shapur II spent much of his 70-year reign on the battlefield. According to early Islamic sources, he earned the name “Shapur of the Shoulders” (Shabur Dhul-aktaf) for leading Lakhmid Arab prisoners across the desert on a rope threaded through their pierced shoulders. Like Julius Caesar and Alexander, Shapur often dove into battle, knowing his presence could inspire his troops. And he cut a heroic figure. A Roman witness reported that in battle he “exchanged his crown for a golden helmet in the shape of a ram’s head, set with precious stones.”

From 337 to 361, Shapur waged aggressive campaigns against the Romans on his western borders. He aspired to seize Armenia and the Roman province of Mesopotamia, which included lands west of the Tigris River. Farther west, wealthy Roman Syria was an attractive prize. Its major city, Antioch, was the hub of eastern trade routes and lay astride all roads leading to Egypt and Asia Minor.

Shapur fought nine battles against Constantius II, with limited success. Determined to renew his assault when Julian came to power, the Persian posed a dangerous threat. His heavy cavalry, among the a ncient world’s best, was well suited to fighting on the arid, rolling steppes of Mesopotamia. The Persians also excelled at siege warfare. Like their ancient predecessors the Assyrians, the Sassanid Persians used a variety of siege engines and towers with battering rams. Expert hydro-engineers, they also built dikes and canals to dam river water that, when released, exploded with enough force to batter down a city’s walls. Another tactic was to divert a river in order to flood the lowlands around a city, isolating and slowly starving the inhabitants.

ncient world’s best, was well suited to fighting on the arid, rolling steppes of Mesopotamia. The Persians also excelled at siege warfare. Like their ancient predecessors the Assyrians, the Sassanid Persians used a variety of siege engines and towers with battering rams. Expert hydro-engineers, they also built dikes and canals to dam river water that, when released, exploded with enough force to batter down a city’s walls. Another tactic was to divert a river in order to flood the lowlands around a city, isolating and slowly starving the inhabitants.

Responding to Shapur’s incursions into northern Mesopotamia, Julian moved swiftly to prepare a punitive expedition. At Antioch during the winter of 362, the emperor mobilized Rome’s eastern legions, gathering equipment and supplies. Julian also sought divine support for his campaign from the traditional Roman gods, making blood sacrifices of cattle and other animals. Though raised a Christian, Julian had revealed his allegiance to the Roman traditional gods upon his ascent to the imperial throne, becoming the first non-Christian emperor since the famous conversion in 312 of Constantine, his father’s half-brother.

To view the remainder of this article please purchase the Summer 2010 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History.