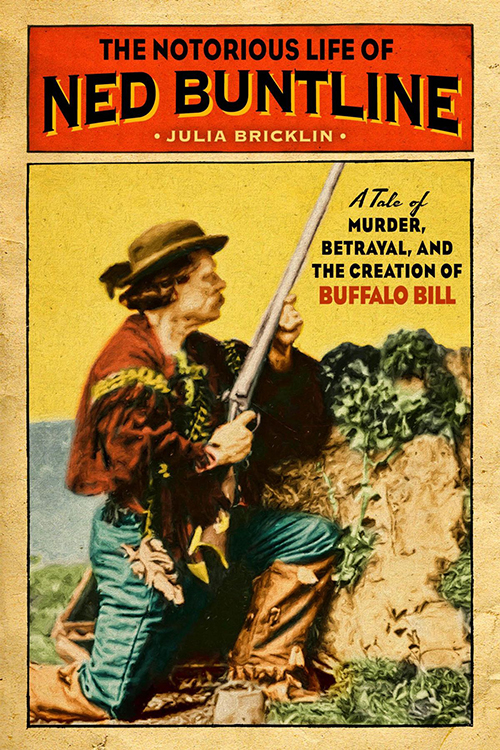

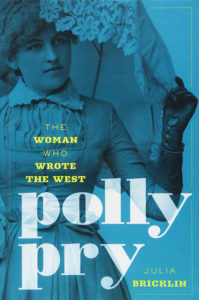

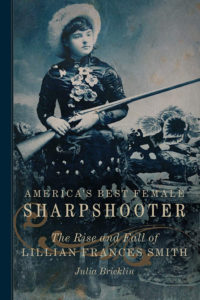

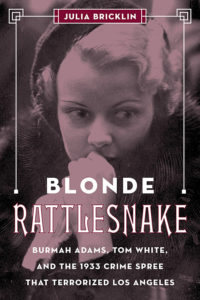

The last person Julia Bricklin wants to write about is some historical figure whose name alone fills volumes. So nothing from Bricklin about Jesse James or Calamity Jane. Instead, she seeks out women and men often overlooked by biographers. The career move has paid off, as Bricklin’s America’s Best Female Sharpshooter:The Rise and Fall of Lillian Frances Smith (2017) was a WILLA Award finalist, Polly Pry: The Woman Who Wrote the West (2018) was a Spur Award finalist and Blonde Rattlesnake: Burmah Adams, Tom White and the 1933 Crime Spree That Terrorized Los Angeles (2019) was nominated for an Agatha Award. Her most recent book is The Notorious Life of Ned Buntline: A Tale of Murder, Betrayal and the Creation of Buffalo Bill (2020). Bricklin, who has worked in the television and film industry and writes scripts for the Legends of the Old West podcast, spoke to Wild West from her California home.

What drew you primarily to the American frontier?

I’m proud to live in the Western United States. There are so many stories still out there for us to unearth. The word “frontier” says it all—it was where people went to get a fresh start or a new identity or ply a trade that was different from previous generations in their families. There’s still a mystique about it.

‘I think it’s perfectly OK to form an opinion of someone who is long dead using the sources one has, as long as one has amassed enough evidence to wade through. The trick is to reconstruct their lives and actions through the lens of their time and their own environment’

What are the challenges of writing biographies about writers?

For me it’s making sure I block out “the noise” of their professional lives. Both Polly Pry and Ned Buntline voiced their political and social opinions outside of their workaday writing. It was tough to separate the bravado from their personal achievements and failings.

Because they were well-known writers of their times, and loudly opinionated, people who recorded their interactions with them often did so with their own bias. These contemporary sources have to be weighed, too.

Lastly, I have to take my own prejudices out of the mix. It think it’s perfectly OK to form an opinion of someone who is long dead using the sources one has, as long as one has amassed enough evidence to wade through. The trick is to reconstruct their lives and actions through the lens of their time and their own environment. That’s the biggest challenge for me, but also the most rewarding if I can pull it off.

Pry or Buntline—who wrote better?

Oh, Buntline was far and away the better writer. It’s certainly unfair to compare the two outside of my own portfolio—Ned was a novelist, while Polly was a newspaper columnist. But since we’re here: Both of them preached a lot, and both made full use of prevalent stereotypes. That’s true of almost all prolific writers of their respective generations. But Ned clearly had better command of the English language. If you read any of his stories, you can see that he mostly uses the active voice, uses subject-verb-object a lot and that his dialog is sharp and crisp. Polly was great at setting a scene, but her prose is littered with fragments and innuendo.

But who had the better pen name?

Polly Pry. You can’t beat that alliteration and allusion!

Jay Monaghan called Buntline the “Great Rascal.” How much of an overstatement or understatement is that title?

It is a massive understatement. Credit to Monaghan—he provided us with a terrific framework with which to start studying Buntline and dime novelists in general. But we have so much more evidence now, in the form of digitized letters, oral histories and newspaper articles from all the places Buntline traveled. The truth is, Buntline was an ambitious and unapologetic troublemaker, and it did not disturb him in the least that his actions caused the deaths and misery of so many people. The flip side of this is that many truly enjoyed his company and his literary talents.

Did Pry open doors for women reporters?

I’m not sure how many doors she opened for women who were strictly fact-based journalists. Polly was this weird hybrid of “sob sister”—someone who used sentimental language to bring attention to problems—and opinion columnist, with a healthy dose of sensationalism. Half the time she wasn’t even on the scene of whatever she was writing about.

But in the first quarter of the 20th century Polly made it possible for women to feel more comfortable in the public sphere in general. Sure, Colorado was already leading the nation in terms of women’s suffrage and social reform. But if letters written to the Denver Post and other Colorado newspapers from, say, 1905 to 1920 are any indication, Polly led huge numbers of women to start showing up at political caucuses and strikes.

What drew you to write about Lillian Frances Smith?

I’m a proud California native, and I was looking for a historical figure from my home state as a topic for, well, Wild West. I stumbled over Smith and could not believe someone had not written about her yet. I soon found out why. Evidence of her was really, really hard to find. It was so rewarding when it all came together after so much digging. I’m still obsessed with her.

How does she compare to Annie Oakley?

If we’re just looking at their shooting, I think they were very evenly matched, though I make the case that Smith may have been a shade better. I worked off contemporary observations of them both. Certainly, Smith had equine competencies that Oakley did not. On the other hand, Oakley was much better at keeping her private life just that and staying within the confines of her “brand.”

I know Smith was deeply hurt when Oakley snubbed her during the Buffalo Bill tour in Europe in 1886. I think she was looking for an “older sister” figure and obviously didn’t find that. Of course, William Cody had promised Oakley a starring role but shoved Smith in there at the last minute. If there had been such a thing as an HR department on [Buffalo Bill’s Wild West], I’m sure history would have been a lot different with these two!

How did you discover Burmah Adams?

I discovered Burmah when I was looking for a photo to use on the cover for California History, a journal I edited until recently. Since it was a fall issue, I thought using an image of a “schoolmarm” from a long time ago would be cool. When I plugged “schoolteacher” into the Los Angeles Library photo archives, my computer was bombarded with images of Burmah, because all the captions were about the schoolteacher she and her husband shot. I wish I could say that I had some gut feeling that such a figure was out there and had not been written about yet—but really, it was just dumb luck.

What’s the difference between researching a 19th-century figure like Buntline and a Depression-Era couple on an L.A. crime spree?

Surprisingly little. Whenever I evaluate whether to write about a person/people, the first thing I do is to see whether there are any legal documents about them. All justice systems are subject to the time and place in which they exist. For me, though, court transcripts remain the most neutral source of information about a topic or person. From there I gather newspaper articles, oral histories, autobiographies and so forth.

How do you balance writing books and writing for periodicals, anthologies and podcasts?

That is a great question, because they really do require different parts of the brain—at least for me. I try to work on any book I might have when I first wake up. I’m not sure why that is. I also tend to work on any podcast scripts in the morning. Afternoons are for magazine features and any essays I might have. Evenings are devoted to research. Of course, in-person research has to be done during the day, so I dedicate special time for that. Thankfully, these different types of projects I undertake usually have staggered due dates.

Which do you prefer?

Going to be hard to deny this to any book publisher, because it’s in writing, but I’ll always have a special place in my heart for magazine features. There’s just something about having the freedom to dive into a topic and present it to a wide audience in a relatively short period of time. One has to make every word count, and so it’s just so gratifying when it comes out.

Did your television/film background draw you to write about Hannah Weinstein or your fascination with obscure figures?

It has more to do with writing about obscure people—specifically, multifaceted obscure people. But I have always loved the business affairs side of creative industries. When push comes to shove, film and television is always about the finances. I know how hard it is to get something on the air, and that’s been true since the days of radio. It just makes Hannah’s story so much more remarkable to me. Here is a woman who, in the man’s world of 1955, managed to convince scores of people on both sides of the pond to invest hundreds of thousands of dollars to create a franchise [The Adventures of Robin Hood TV series] beloved by millions. It does check a lot of boxes for me.

‘I’m thrilled Legends has been letting me research and write about well-known figures from Western history while giving me the latitude to present some themes and details that aren’t the same ol’.

How did the Legends of the Old West podcast come about?

This was a serendipitous opportunity for me, because I’d just freelanced for another podcast company and found that I really enjoyed it. Black Barrel Media (the producers) are really on the forefront of audible entertainment, and I’m grateful for the work. So many history podcasts are just recitations of Wikipedia pages, really. I’m thrilled Legends has been letting me research and write about well-known figures from Western history while giving me the latitude to present some themes and details that aren’t the “same ol.” I think writing for the ear has actually made me a better writer for the eye. It’s challenging, though.

What advice do you have for beginning biographers?

Ask yourself, What’s my two-sentence pitch for this person’s life, as I wish to write it? If you feel that this person’s life represents some themes that would be of interest to thousands of people, then go for it! If your answer is, My grandma would be so proud of me for this genealogy, then you really need to ask yourself if it’s worth it.

On the practical side, I’d go to Worldcat (the ultimate database of things that have been published about a topic) and punch in your person. If it looks like he or she has been written to death, I’d ask yourself what you can add that’s new. It will also give you an idea of what sources are out there for you to mine.

What’s next for you?

I hope to keep writing history-based podcast scripts. I’m so proud of the work we did representing Bass Reeves, Ned Buntline, Tom Horn and so on. I’m also planning to take Lillian Smith to the next level somehow, in terms of film or television or streaming. I know that’s a long and difficult road, but it’s time for Miss Smith to get her due.